When Louis Armstrong Conquered Chicago

Grammy-winner Ricky Riccardi tells the story of a milestone moment in American music in this extract from his new book

If you want to understand 20th century American music, you really must start with Louis Armstrong.

Armstrong changed the entire pulse of commercial music—inventing rhythmic phrases nobody had heard before. This allowed him to create new melodies, which he performed with a virtuosity unsurpassed in popular music.

This sounds like hype, but it’s all true—and documented on recordings.

Other musicians always wanted to examine Armstrong’s horn. They were certain it must be some kind of trick instrument. Otherwise, how could he get those amazing sounds out of it?

And that was just what he did with his trumpet. Armstrong was even more influential with his voice—American singing would never be the same after the reign of King Louis.

Most people have no idea of this. That’s because Armstrong was such a skilled entertainer. He made it all look easy. After he became a pop culture star, most of his audience had no clue how much he had contributed as an artist.

But there’s one person who knows all this better than anyone else on the planet. His name is Ricky Riccardi.

I first encountered Riccardi when he was just a music blogger. I read lots of jazz blogs back then, but Riccardi’s was different. It focused on just one artist—Louis Armstrong.

I thought I knew a lot about Louis Armstrong—after all, I’ve been studying his music since my teen years. But Riccardi was constantly telling me new things about my jazz hero. Ricky knew all the recordings, all the bootlegs, all the anecdotes, all the details.

Even better, he loved every bit of it.

So when Ricky got hired as archivist by the Louis Armstrong House Museum in 2009, it made perfect sense. Never before have I seen a person better suited for his job.

His current title is Director of Research Collections. But his outreach work is just as important as his research work.

Three days ago, he got rewarded with a much deserved Grammy—for his liner notes to a stellar reissue of Louis Armstrong’s debut recordings, back in 1923, with King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band.

I call them liner notes, but that doesn’t do justice to Ricky’s work on the project. The recordings came with an 80-page book.

But this week he did something even grander.

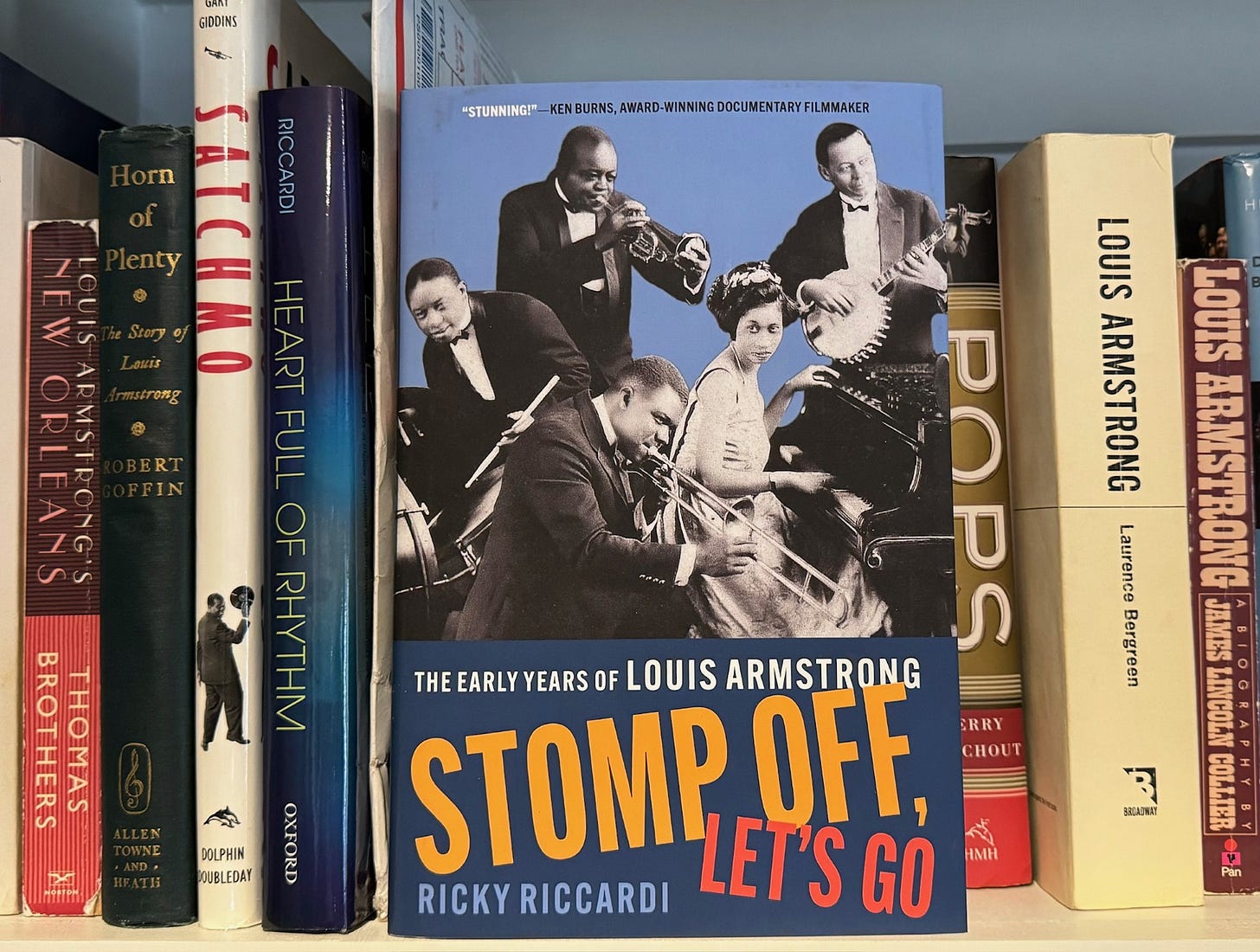

For the last 15 years, more or less, Riccardi has been writing the ultimate biography of Louis Armstrong. But he has been doing it in reverse order.

He started by publishing a book on the final years of Armstrong’s life, What a Wonderful World (2011)—celebrating a period that many jazz scholars have undervalued.

Then he tackled Armstrong’s middle years in a separate volume. This work, entitled Heart Full of Rhythm (2020), covers Armstrong’s middle period, from 1929 to 1947.

That left one obvious gap—the origin story of Louis Armstrong. And it’s the best part of the tale. He covers it in a new book released two days ago.

There’s never been a more inspiring rags-to-riches story in American music. Armstrong rose from a childhood of hardship and poverty, and conquered the whole entertainment world in the 1920s.

Riccardi’s account of this triumphant period, published by Oxford University Press, is called Stomp Off, Let’s Go: The Early Years of Louis Armstrong.

I highly recommend it.

Even better, I have permission from the author and publisher to share an extract with you—and it’s my favorite part of the story.

Below is Riccardi’s account of the day Louis Armstrong left New Orleans behind, and launched his star-studded career in Chicago.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

When Louis Armstrong Conquered Chicago

By Ricky Riccardi

“I arrived in Chicago about eleven o’clock the night of July 8, 1922, I’ll never forget it, at the Illinois Central Station at Twelfth and Michigan Avenue,” Armstrong recalled in 1947. He had enjoyed the 25- hour train ride as he'd lucked out and found an empty seat next to a woman who was a friend of Mayann—and who was carrying “a big basket of good old southern fried chicken” for her family. Louis “lived and ate like a king, all the way to Chicago.”

“All out for Chicago, last stop!” the conductor hollered.

“A funny feeling started running up and down my spine,” Armstrong said. By waiting until the evening, he had already missed the early morning train Joe Oliver had told him to take— what if Oliver wasn’t waiting for him at the station? He couldn’t hide his anxiety. “If anyone would have been watching me closely, they could have easily seen, that I was a country boy from the way my eyes were wide open and looked,” he wrote.

He waited by himself at the station for over an hour before a policeman asked if he needed help.

“Yes sir,” Armstrong responded. “I came in from New Orleans. I am a cornet player. And I came up here to join Joe Oliver’s Jazz Band.”

“Oh, you’re the young man who’s to join King Oliver’s Band at the Lincoln Garden,” the officer responded with a smile.

Armstrong was perplexed for a moment, hearing his mentor’s royal moniker. “In New Orleans it was just plain Joe Oliver,” he recalled.

The officer explained that Oliver had been waiting for him earlier in the day but had to go to work, leaving word to be on the lookout for his new cornet man. He set Armstrong up in a cab and sent him on his way.

“I thanked the cop for being so kind,” Armstrong said. “Something a little different from the cops down south. They usually whip your head and then ask you questions.”

Armstrong’s cab eventually pulled up to 459 E. 31st Street on the corner of Cottage Grove, home of the Lincoln Gardens. A painted canvas sign hung outside advertising “King Oliver and His Creole Jazz Band.” Armstrong could hear the music from the street and became consumed with self- doubt. “My Gawd, I wonder if I’m good enough to play in that band,” he thought to himself.

The venue’s huge lobby felt like it was “a block long” as he nervously navigated the crowded hallway before entering the colorful cabaret. Once inside, he would have been gobsmacked by the big crystal ball that hung from the center ceiling— a precursor to a later generation’s “disco ball.” “A couple of spotlights shone on the big ball as it turned and threw reflected spots of lights all over the room and the dancers,” frequent visitor and future drummer George Wettling remembered. The ceiling was lowered with chicken wire, across which “great bunches of artificial maple leaves” were hung.

Perhaps the first person to spot Armstrong was trombonist Preston Jackson. The New Orleans native had moved to Chicago several years earlier and had spent many nights shadowing Oliver’s trombonist Honore Dutrey. “I was sitting on the stand,” Jackson said of Armstrong’s arrival. “I’ll never forget it, he had on a sailor [straw hat] with a brown suit, tan shoes.”

Oliver was in the middle of passing out sheet music to the other members of the band when he spotted his protégé. “And My My My... One would have thought that ‘Hell’ broke loose,” Armstrong wrote.

About Armstrong’s appearance, Oliver later told trombonist Clyde Bernhardt, “Everything was all right about him but the way he looked. He was just as greasy as a pig!” Oliver also said Armstrong “had a suitcase, it was so raggedy, it had ropes all tied around it to hold it together.” Oliver’s pianist, Bertha Bookman, recalled that Armstrong was “carrying his cornet wrapped in a black bag.”

Armstrong was thrilled to be reunited with fellow New Orleanians, including drummer Baby Dodds from the Fate Marable band, clarinetist Johnny Dodds from Kid Ory’s band, and trombonist Honore Dutrey, brother of clarinetist Sam Dutrey. He probably didn’t remember bassist Bill Johnson, who had left home when Armstrong was still a boy, but he knew of Johnson's reputation due to the success of the Original Creole Band. But looming above everyone was Oliver. “Gee Son, I’m really proud of you,” Oliver said.

Oliver told Armstrong to take a seat and enjoy the floor show, which was introduced by emcee Collwell “King” Jones, “a little fellow with a great big voice” who spoke with a comedic West Indian accent but, according to Armstrong, was actually from Mississippi. The New York Amsterdam News later referred to Jones as “one of the greatest laugh provokers on the continent” and a “remarkable humorist.” Though remembered for malaprop-heavy monologues that probably reeked of minstrelsy, the bespectacled Jones represented Armstrong’s first taste of a certain kind of performer in Chicago.

“Truly, he has a personality that has its effect upon both the orchestra and onlookers,” the Chicago Defender reported, adding, “He believes in himself, and a little more self-confidence will put a lot of us over.” These lessons would not be lost on young Armstrong.

At the end of the evening, Oliver introduced Armstrong to the owner of the Lincoln Gardens, an older white woman named Florence Majors, who didn’t say much but had stuck by Oliver through his issues with the musicians’ union, and the venue's manager, a 44- year-old African American man named Charles “Bud” Redd.

“Joe, where in the hell did you get that little country sommitch?” Redd asked, breaking up the band in the process.

“Don’t kid that boy, Budd, he don’t know anything about that kind of ribbing.” Oliver responded. “You might frighten the kid.”

“Joe was right,” Armstrong later admitted, “Because the whole time I worked there, I was a little shaky of Budd.”

Armstrong and Oliver left the Lincoln Gardens together and headed to Oliver’s apartment, located right around the corner at East 32nd Street and South Vernon Avenue. There Louis had a joyous reunion with Stella Oliver and her daughter Ruby over a big meal. “[Stella] fed me the same way she’d feed Joe a big dish of red beans and rice, a half a loaf of bread, and a bucket of good ice cold lemonade,” Louis remembered. “Yum Yum....”

Oliver had taken the liberty of setting Armstrong up with an apartment at 3412 South Wabash Avenue, where the landlady was a “goodlooking middle aged Creole yellow gal with pretty big eyes” whom Armstrong remembered as “Filo.” A quick search of the property records shows that she was Philo Atkins, originally born in New Orleans and the wife of trombonist Ed Atkins, who would go on to record with both Armstrong and Oliver the following year.

As they rode the cab to Philo Atkins’s apartment building, Oliver told Armstrong his room would have a private bath.

“What’s a private bath?” Armstrong asked.

“Listen, you little slew-foot sommitch, don’t be so damn dumb,” Oliver said with a “funny” look.

“But he had forgot, that he must have wondered the same thing when he first came up north,” Armstrong reflected. “Because in New Orleans the neighborhood we lived, we never heard of such a thing as a bath tub Period...Letlone a private bath....Savy?”

After catching up on some sleep, Armstrong took advantage of his new private bath, got dressed, and went out for a long walk, stunned by the beautiful African American neighborhood he found himself in. “The reason why I was so amazed over South Parkway is because, such a street in New Orleans, with all those highpowered homes and apartments, nothing but white folks lived on a street like that... And nothing but the Filthy Rich ones at that,” he wrote. “I just could not get [over] the idea, that it was a little difference between the north and the south (a little differnt [sic] anyway) and the colored people were a little more respected and appreciated.”

A touching moment occurred when Armstrong passed Olivet Baptist Church, located almost next door to the Lincoln Gardens. One of the last songs he had played in New Orleans at the funeral for Eddie Vincent’s father had been the hymn “Abide With Me.” “The first Sunday I was in Chicago, I took a little stroll, you know, trying to look the city over, especially in my neighborhood as much as I could see,” he said. “And I happen to pass by a church at 31st and South Parkway. Olivet Church, I’ll never forget it, it was about 7:00 in the evening and what I want to make clear was a coincidence: the choir was singing ‘Abide With Me.’ Isn’t that funny?”

Armstrong was also comforted by numerous friends from New Orleans he met as he strolled through Chicago. “Now with so many New Orleans Boys and Gals I knew I could not get homesick as I had done so many times before when I left New Orleans,” he wrote. He was experiencing the effects of the Great Migration right before his eyes, squashing any trepidations he might have had about moving up north.

After a nap, Armstrong got dressed, putting on his old “Roast Beef ”— “P.S. that was what we called an old ragged Tuxedo,” he later explained. “Of course, I had it all pressed up and fixed so good that no one would ever notice it, unless they were real close and noticed the patches here and there. Any way—I was real sharp, at least I thought I was anyway.”

Armstrong arrived at the Lincoln Gardens and said hello to Mrs. Major, Bud Redd, and King Jones before taking his place on the bandstand. Baby Dodds said the band lined up in a row in the “New Orleans tradition.” Bill Johnson was farthest to the left, standing next to Bertha Bookman’s piano. Johnny Dodds was next, with Armstrong taking his place in the center next to Oliver. Honore Dutrey would be to the right of the cornetists and Baby Dodds’s drumset would be on the far right. “The lineup at the Lincoln Gardens bandstand was arranged in such a way as to make the music sound better,” Dodds said. “In other words, it gave good balance and improved the sound.”

After he took his place on the stage, Armstrong’s nerves acted up again. “It’s a funny thing about the music game and Show Business,” he later reminisced, “no matter how long a person has been in the profession, their opening Night always seem to give the feeling that you have little Butterflies moving around in your stomach.”

Any butterflies disappeared as soon as the music began. “We cracked down on the first note and that band sounded so good to me after the first note that I just fell right in like old times,” Armstrong wrote. “Papa Joe really did blow that horn. The first number went down so well we had to take an encore.” Armstrong was content to take a back seat to his mentor, later writing: “I did not actually take a solo until the evening was almost over. I never tried to go over him, because Papa Joe was the man and I felt any glory that should come to me must go to him. I wanted him to have all the praise. To me Joe Oliver blew enough Horn for the both of us. I could just sit and listen to him and play second to his lead. I never dreamed of trying to steal the show or any of that silly rot.”

Armstrong did get a few moments in the spotlight that night, but only alongside Oliver when the two men discovered a new way to join forces. “During my first night on the job, while things were going down in order, King and I stumbled upon a little something that no other two trumpeters together ever thought of,” he recalled. “While the band was just swinging, the King would lean over to me, moving his valves on his trumpet, make notes, the notes that he was going to make when the break in the tune came. I’d listen, and at the same time, I’d be figuring out my second to his lead. When the break would come, I’d have my part to blend right along with his. The crowd would go mad over it!”

I had the pleasure of seeing Satchmo in Minneapolis in the 50s. My father took my brother and I to see him.

Fantastic / my music teacher Tommy Thomas (1901-1995) was from Chicago - he told me stories of his Sunday visits to Louis house for jam

Sessions - Tommy was a sideman in those days with Bix Beiderbecke and Benny Goodman .