When Duke Ellington Came to North Dakota

Or how a milestone moment in American music happened in a most unlikely place

This week marks the 124th anniversary of jazz bandleader Duke Ellington’s birth.

If you think Ellington—born in the last year of the nineteenth century—is forgotten in the digital age, think again. Celebrations took place all over the world.

Several of my friends reported back from a big Duke Ellington conference in Paris. Others focused on Duke for their International Jazz Day festivities yesterday. Some Ellington lovers just shared their love on social media.

As a loyal subject of this Duke, I want to get into the act, too. So today I’m writing about one of my favorite moments in the history of his dukedom—his dance concert in Fargo, North Dakota.

That may not sound like much. But, for me, it’s one of the great moments in American music history.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

When Duke Ellington Came to North Dakota

By Ted Gioia

Most bootleg recordings are sad stuff indeed.

I understand why obsessive fans seek them out. They’re so desperate to hear music by a favored band that they even settle for poorly-recorded tracks from an average concert. But those bootleg songs were almost certainly performed better on a studio album.

Of course, that doesn’t matter for the true believers. They’re like art collectors who can’t afford an Old Master painting—so they settle for a rough sketch or notebook jotting instead.

But the value of a bootleg varies in direct proportion with the skill of the musicians. Some chart-climbing bands lack the musicianship to play live in concert what tech wizardry enabled in the studio. Listening to their bootlegs is a depressing exercise. But on the other extreme, we find a handful of world-class talents who thrive in the heat and spontaneity of live performance.

The jazz world is blessed with more than a few of those remarkable artists. As a result some of my most cherished jazz albums were originally bootlegs—preserved by happenstance or, in some instances, by illegal taping in violation of IP laws and recording contracts.

Yet what fan of bebop would relinquish Jazz at Massey Hall, that amazing demonstration of bebop prowess recorded in Toronto on May 11, 1953? That’s true even though altoist Charlie Parker, playing on a borrowed horn, had to be billed on the original release as Charlie Chan (in deference to his wife Chan Parker) because of legal issues, and Dizzy Gillespie complained that he didn’t get paid “for years and years.” Or what about the recent Thelonious Monk album Palo Alto, recorded by a custodian at a high school in 1968—and still almost blocked by IP concerns more than 50 years later?

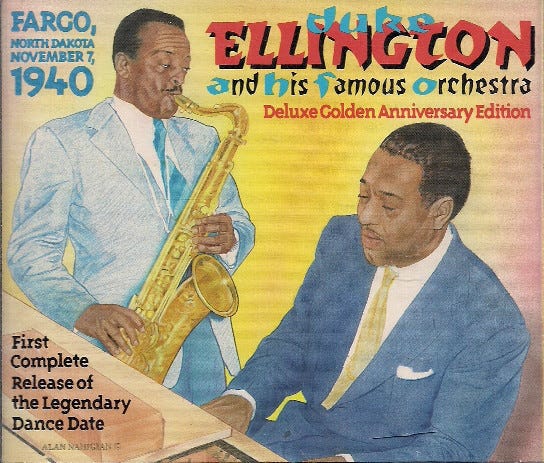

But of all the jazz bootlegs in the long history of the music my favorite by far is one that, at first glance, would seem an unlikely classic. I’m referring to Duke Ellington’s performance at a dance in Fargo, North Dakota on November 7, 1940.

During the course of his illustrious career, Duke Ellington played everywhere from Carnegie Hall to the White House. Hundreds of his concerts were recorded. So it’s perhaps surprising that a Midwest dance would leave such a mark. But it did.

Fargo, in 1940, had a population of just 32 thousand people—and it’s reasonable to assume that few were sophisticated jazz fans. But jazz was the popular dance music of the day, and Ellington had plenty of experience playing for dancers. In some ways, this was a far more familiar setting for him than Carnegie Hall.

I suspect that the whole band felt that way. Fargo City Auditorium was as comfortable and stress-free environment as these musicians would encounter during their titanic road journeys.

And don’t minimize the impact of dancers on the musicians. Cynical commentators will tell you that it’s demeaning for world-class musicians to play for small town dancers, but I would urge you to take another perspective. When musicians play for dancers, they can see immediately the impact of their music in the movements and enthusiasm on the ballroom floor. For jazz players of that generation, this was an inspiring situation, not constricting or disrespectful in the least.

And, more to the point, this was Ellington’s best band—in my opinion, and according to many other knowledgeable listeners. Ben Webster, who had recently joined the Ellington orchestra, was the best tenor sax soloist ever to play in the band, but he would only stay with Duke for three years. The Fargo concert is one of his finest moments—and even he would have admitted it. Jimmie Blanton, the most influential bassist of the era, would spend even less time with Ellington, signing on with the band in 1939, but dying from tuberculosis in 1942 at just age 23.

Because of the prominence of these two famous musicians, many people call this the “Blanton-Webster” edition of the Ellington band. But this shouldn’t blind you to the caliber of the other soloists who came to Fargo that evening, which included longtime Ellington stalwarts Johnny Hodges on alto sax, Harry Carney on baritone sax, Barney Bigard on clarinet, Tricky Sam Nanton on trombone, Rex Stewart on cornet, and Sonny Greer on drums, among others.

“We had no thoughts whatsoever of recording anything that anybody would be listening to 40 or 50 or 60 years down the line.”

This historic record would never have happened except for two local jazz fans, Jack Towers and Dick Burris, who pestered Ellington’s manager, the William Morris Agency, for permission to record the proceedings. Their equipment consisted of a portable acetate disc cutter connected to three microphones—not bad for bootleggers, circa 1940. The agency gave the go-ahead, provided the two fans got Ellington’s permission before the dance, and agreed not to release the music commercially.

“We had no thoughts other than just the thrill of being there, recording, and having something we could play for our own amazement,” Towers remarked in a 2001 interview. “We had no thoughts whatsoever of recording anything that anybody would be listening to 40 or 50 or 60 years down the line.”

The dance would take place in the Crystal Ballroom, on the second floor of the Fargo City Auditorium. The two young men searched out Ellington before the gig, and asked whether they could record the proceedings. Duke thought it over, and expressed some concern—but not because of intellectual property.

As always, Ellington was thinking about the quality of the music. The trumpets were in “bad shape” he responded.

In a jazz big band on the road, that could mean many things—too much partying, too little sleep, or even some genuine problem with instruments. But in this case, Ellington probably was referring to the recent departure of trumpeter Cootie Williams from the band, and the arrival of substitute Ray Nance, who was making his first appearance with the orchestra. Ellington nonetheless agreed to the proposal, which included broadcasting some of the performance on local radio station KVOX, and putting almost all of it on disc.

Somewhere between 600 and 800 people showed up—quite a crowd when you consider the small local population. They paid $1.30 for a ticket, and came ready to dance.

The setting was far from elegant. The hall didn’t even have music stands—performers propped up their charts on satchels or makeshift devices. But it did have a large glass ball hanging from the ceiling to reflect the lights and give a kind of sparkle to even the most humdrum performances.

It doesn’t seem like much. But over the years, a number of name performers came through Fargo, with everyone from Louis Armstrong to Lawrence Welk playing for the locals.

As the night wore on, the participants started to get a sense of the magic of that particular date. During intermissions, Towers and Burris played back some of the discs for the band members. They were fascinated, and even Ellington asked for a playback of one of the songs. Given the limitations of the equipment and the inexperience of the the two amateur recording engineers, the sound quality was surprisingly good. The quality of the music even better. Something special was happening, and in Fargo, North Dakota, of all places.

Even so, these tracks might never have been heard by jazz fans, except that one of the few private copies circulating among Ellington fans (and musicians—Ben Webster demanded his own copy after hearing the results) got turned into a bootleg. This helped establish the cult-like status of the Fargo music.

The Ellington family seemed undecided between suing or releasing their own “official” version. They eventually took the latter course.

And with outstanding results. In fact, Duke Ellington at Fargo, 1940 Live even won a Grammy as best jazz big band album—but in 1980, some forty years after it was recorded. Another four decades have transpired since then, and this record has only become more cherished and legendary with the intervening years. For those who want to hear what the greatest jazz band of the era sounded like at the top of its game, this is the place to go.

That’s because, even if the citizens of Fargo just showed up for some carefree dancing, Duke Ellington wasn’t going to hide his light under a bushel (mostly wheat in that region). Those who came that evening would hear some of his most ambitious and assertive charts—for example, “Ko-Ko,” a very intense instrumental that’s hardly the background for a romantic spin on the ballroom floor. This is more of a devil’s dance, infernal and insistent.

But Ellington could also serve up a lovey-dovey ballad when the occasion demanded. And a dance gig always served as a proper occasion. Few popular songs were more beloved by mainstream America back then than Hoagy Carmichael’s Star Dust, and Ben Webster was featured as soloist. He was so pleased with what he played that night that he contacted Jack Towers for additional copies for his personal enjoyment in later years.

Finally, here’s the band playing “Harlem Air Shaft,” one of Ellington’s most ingenious compositions from the era, for the dancers in Fargo.

What a great Thursday night in Fargo, North Dakota. And it was a great night for American music too.

In the current day, when old jazz often gets treated like some kind of museum exhibit, it’s endearing to find so much artistry embedded in a casual dance in a small town. I’m sure the band felt the vibe and knew they had done something special.

But they didn’t have much time to think it over. They could rest for a few hours, but soon had to get back on the bus. They had a gig the next day in Duluth.

My grandfather was there at the legendary Fargo show! He was a teenager living in South Dakota, and he was such a Duke Ellington fanboy he followed the band around across several states, seeing every gig he possibly could. Thanks for another great article about one of my favorite live albums of all time!

My grandfather, who was not by any means a "jazz fan", told me of the time Duke Ellington's orchestra came to his part of Oklahoma. I believe it was a converted barn they performed in. The way he described it was equivalent to a presidential visit. Both my grandparents were Okie farmers, and hearing him describe that event from his youth made me realize Ellington's contribution to American culture was so much deeper than music.