When a Single Person Controlled the Copyright on All Music (Even Blank Music Paper)

Music copyright law is a mess today—but it's always been that way

Get three songwriters around a table, and they will soon start complaining about copyright lawsuits. Nobody is immune, not even the superstars.

Or especially not the superstars.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

That’s because the lawyers leave you alone until you write a huge hit song. You can compose duds for decades, and they don’t care a whit about your copyrights. But if you start making serious money, they find some similar tune—that’s not hard to do—and take you to court.

They’ve gone after the Beatles, Johnny Cash, Madonna, Brian Wilson, Taylor Swift, Radiohead, Ed Sheeran, Led Zeppelin, Rod Stewart, and many, many others. Sometimes it gets ridiculous—for example, when John Fogarty was sued for sounding too much like himself! But the lawsuits keep coming.

People tell me it was never this bad before. But they’re wrong. The music copyright situation was even crazier 500 years ago.

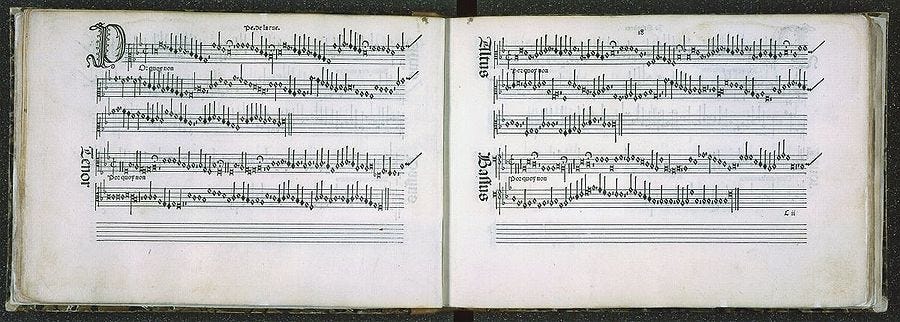

The Italians took the lead in this, and it all started with Ottaviano Petrucci gaining a patent from the Venetian Senate for publishing polyphonic music with a printing press back in 1498. Andrea Antico secured a similar privilege from Pope Leo X, which covered the Papal States.

It’s hard to imagine a Pope making decisions on music IP, but that was how the game was played back then. In 1516, Pope Leo actually took away Petrucci’s monopoly on organ music, and gave it to Antico instead. You had to please the pontiff to publish pieces for the pipes.

Over time, this practice spread elsewhere. In a famous case, the composer Lully was granted total control over all operas performed in France. He died a very wealthy man—with five houses in Paris and two in the country. His estate was valued at 800,000 livres—some 500 times the salary of a typical court musician.

But the most extreme case of music copyright comes from Elizabethan England. Here the Queen gave William Byrd and Thomas Tallis a patent covering all music publishing for a period of 21 years. Not only did the two composers secure a monopoly over English music, but they also could prevent retailers or other entrepreneurs in the country from selling “songs made and printed in any foreign country.”

If anybody violated this patent, the fine was 40 shillings. And the music itself was seized and given to Tallis and Byrd. They probably had quite a nice private library of scores by the time the patent expired.

But that’s not all. Byrd and Tallis’s stranglehold on music was so extreme it even covered the printing of blank music paper. That meant that other composers had to pay Tallis and Byrd even before they had written down a single note. Not even the Marvin Gaye estate makes those kinds of demands.

Tallis died a decade after the patent was granted—putting Byrd in sole charge of English music. I’d like to tell you that he exercised his monopoly with a fair and open mind—especially because I so greatly esteem Byrd’s music, and also I’d like to think that composers are better at arts management than profit-driven businesses. But the flourishing of music publishing in England after the expiration of the patent—when, for a brief spell, anybody could issue scores—makes clear that Byrd did more to constrain than empower other composers.

I’ve also speculated elsewhere that Byrd may have limited the publication of lute music—possibly because the lute was the instrument of seducers. I note that the most important collection of lute music in English history, John Dowland’s First Booke of Songes or Ayres, was published in 1597—immediately after Byrd’s patent expired.

According to scholar Graham Freeman, the year 1597 was “a high point in the history of English music publishing.” I don’t think that’s a coincidence. Other composers and publishers were just waiting for the monopoly to end.

Byrd did pay a price for this patronage. He had to take a loyalty oath to Queen Elizabeth—acknowledging her not only as sovereign but also as the ultimate authority on religious matters. This was, of course, standard practice, but William Byrd was a closet Catholic, who maintained allegiance to the Church of Rome at a time when this was absolutely forbidden in England.

Consider the case of Edmund Campion, a distinguished Oxford graduate who also enjoyed the patronage of nobility. But this hardly helped him when his advocacy of Catholicism was discovered. He was arrested, imprisoned in the Tower of London, tortured on the rack, and then executed.

William Byrd, who was the exact same age as Campion (41 when he died), no doubt paid close attention to the brutal treatment of his contemporary—who he may well have known personally. Some people believe that Byrd’s setting of Psalm 78 (Deus venerunt gentes) was his coded way of paying tribute to Campion.

This double life was risky, but somehow Byrd pulled it off. It didn’t hurt that Queen Elizabeth was such a fervent admirer of his work—this may have prevented a more intense inquiry into the composer’s private devotions. But it couldn’t have been easy for him to operate as the most esteemed living composer of the Church of England while attending forbidden and treasonous services in secret.

The practice of royal patents for music eventually died out. But even in the 18th century, Joseph Bodin de Boismortier received a royal license for music engraving in France. He was not an esteemed composer—and some say he was incapable of conducting his own works because his mind wandered so much. But the favoritism of Louis XV was more valuable than talent—and when others criticized his music, Boismortier would brag about how much money he was making.

I take some comfort in these abuses of power. They make the ridiculous copyright lawsuits of the current day appear modest by comparison. Imagine if the President of the United States assigned total control of American music to a favorite recording artist. (“Hey bro, you’re gonna need Ted Nugent’s permission to make that album.”) It sounds like a comedy skit on Saturday Night Live—but if we operated under Elizabethan rules, this could easily happen.

And we can also learn from these bizarre precedents. First they make clear that strong IP laws don’t always benefit creators—and often inhibit rather than promote artistry. But the saddest conclusion I draw from all this is that musicians themselves can be just as oppressive as governments or bureaucracies if you give them too much power. Of course, there’s little risk of that happening in our current musical culture.

This is flawless: “You had to please the pontiff to publish pieces for the pipes.” 🤣

Copyright on the blank paper is hilarious. Reminds me of when ASCAP started demanding license fees from makers of blank cassettes and dat tapes on the assumption that songwriters were owed for potential copies made on the media. I don’t know how that worked out.