What Happened to Sly Stone?

At age 80, he tells his tale—but is it a story of recovery, or mere survival?

Some musicians walk away from their careers. Others just disappear.

Bobbie Gentry hasn’t been seen in public since 1982. Connie Converse vanished in 1974. Kid Bailey recorded two legendary blues songs at a 1929 session in Memphis—then disappeared completely.

Those are mysteries.

But too many cases of vanishing musicians are out-and-out tragedies.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

That’s especially true for a tiny group of self-destructive superstars who disappear from the stage—but still show up in newspapers. For the worst possible reasons.

For several decades, that’s the unsatisfying role played by Sly Stone, a music legend who dropped from view in 1987. In later years, he occasionally resurfaced, but there was no comeback—more like a series of comedowns.

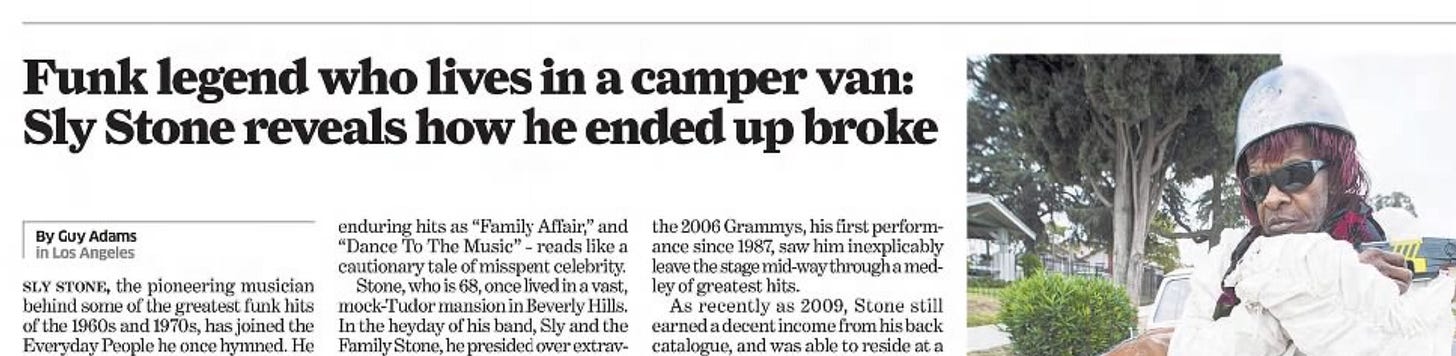

When you read about him in the news, you wished you hadn’t. Consider this 2011 story in The Independent:

Or this profile in the Los Angeles Times:

For a few triumphant years, Sly Stone was at the pinnacle of the music world, releasing hit after hit—and then his career was over.

And not because of fickle fans. But because of Sly himself.

The fans wanted more.

They remembered when Sly Stone was everywhere all at once: On TV or the cover of Rolling Stone, or at Woodstock (the concert and the film). Or playing to capacity crowds at Madison Square Garden (where Stone got married in front of 21,000 people).

And especially on the radio. Between 1967 and 1971, Sly and the Family Stone were constantly in the airwaves—with five top ten singles, including three that reached the top of the chart.

These include my all-time favorite summer song:

Sly Stone had a whole new sound. He called it psychedelic soul. And every record label wanted its own version of it.

Sly later accused Motown of borrowing his sound and style to launch the careers of Michael Jackson and the Jackson 5. The hit Broadway musical Hair slyly reflected the same stoned ethos. The Temptations were also tempted to change their approach after Sly’s rise to fame.

It was a defining sound of the era.

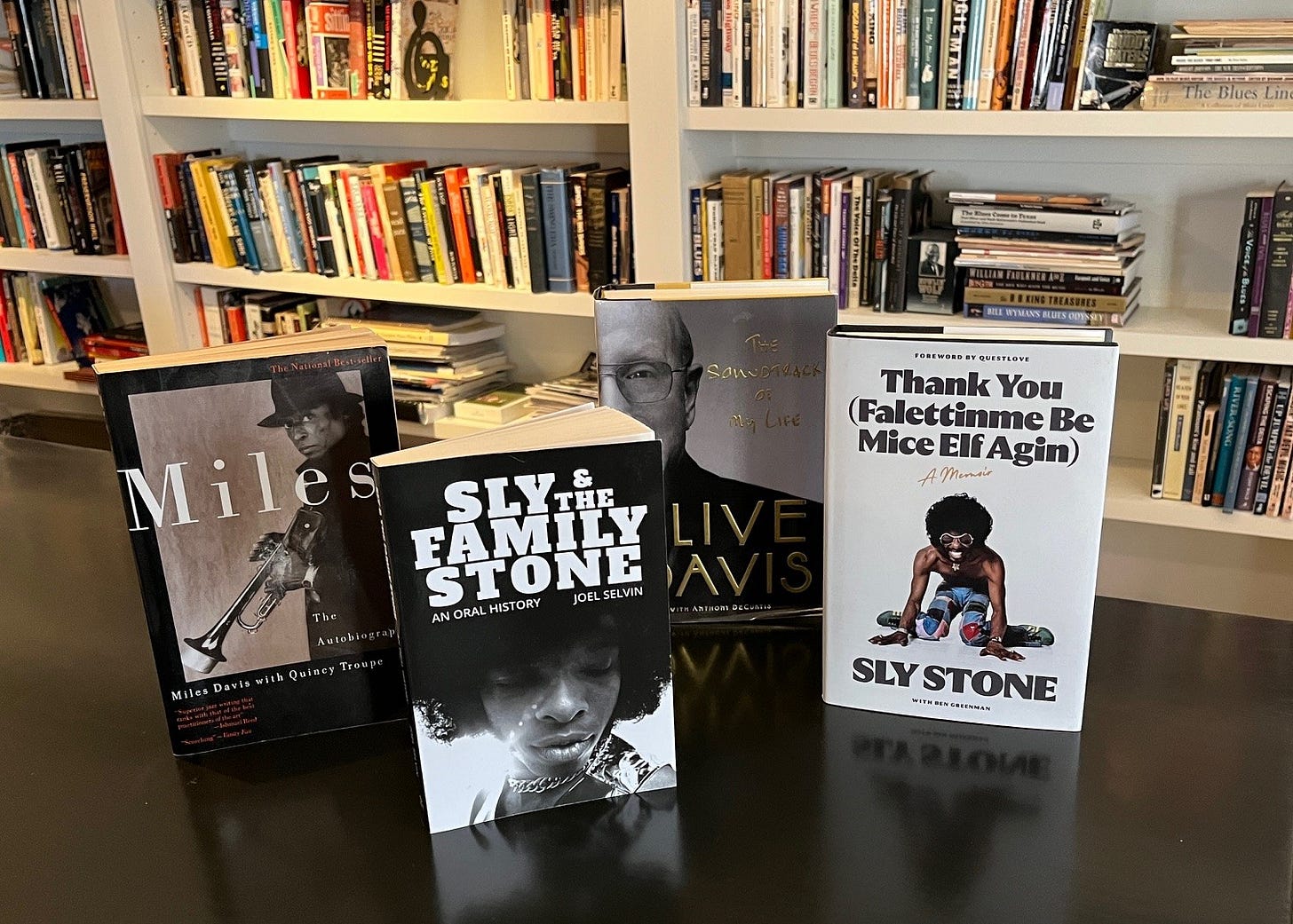

Miles Davis was especially obsessed with Sly Stone (and mentions him 12 separate times in his autobiography). When Davis was working on his historic Bitches Brew album, he spent time at home listening intensely to Sly and the Family Stone.

“When I first heard Sly,” Miles later recalled, “I almost wore out those first two or three records, ‘Dance to the Music,’ ‘Stand’ and ‘Everybody is a Star.’” When Davis recorded On the Corner in 1972, Sly Stone’s influence was so pervasive that jazz fans accused the trumpeter of abandoning the genre in pursuit of funk-oriented dance music.

But it was more than just music. Stone’s style of dress also set the tone for that era—it was a key part of the package. So Miles imitated Sly’s clothes as much as his sound.

Stone had a whole philosophy of fashion. He didn’t like the idea of band uniforms, but he dictated key colors, especially red, white and black. And the outfits (often picked up in secondhand stores) worked endless psychedelic variations on these hues. “He was the first person I met that was into a thematic thing,” later recalled saxophonist Jerry Martini.

But behind the scenes, Sly Stone was already on a destructive path. Before long, making music of any sort—recording new songs or just playing the old ones—was more than he could handle.

Band manager Hamp “Bubba Banks” later shared details with rock historian Joel Selvin:

[Sly] was just out of it. He was all the way out. There wasn’t anything happening no more. It was over. He was through. He was doing shit you would expect to see in some kind of institution….He and Freddie [Stone] walked around the house all day like zombies. I started sleeping with a pistol….

Sly Stone now tells the story himself in his memoir Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin). The book itself is something of a miracle, given the downward path Sly Stone has traversed since those glory days.

From the start, success brought strain. “For energy, for traveling and performing, I took something to take me up,” Stone explains. “That was coke, mostly….But then I’d have to bring myself back down with pills.”

Audiences increasingly suffered along with the band members. “The road had taken its toll,” Stone writes. “I didn’t miss many shows, but I was sometimes late, and when I showed the shows were sometimes as short as the candle I was burning at both ends.”

The money disappeared as fast as it came. “I was buying shit left and right,” Stone admits, “including too many cars. At one point there were thirteen.” From Jaguar to Mercedes, he had all the status vehicles at his command.

But his concerts no longer delivered the goods—especially when fans sat waiting for the star performer to arrive. After a disastrous booking at the Apollo, Stone saw the verdict in a reviewer’s headline: “A Has-Been at 26? Sly Stone Hits a Slump, Turns Into Lackluster No-Show.”

A cancelled concert at Grant Park in Chicago generated even worse press—the New York Times blamed a huge riot, lasting 5 hours and resulting in 150 arrests and 25 people hospitalized, on Sly and the Family Stone, who “refused to play.” Band members griped that the riot had already started, forcing them to cancel—but the damage was already done.

Recording sessions were no better. “He would book studios and not show up,” complained label exec Stephen Paley. In desperation, the label installed a 16-track recording unit in Stone’s apartment—hoping that it would result in an album.

When Miles visited Stone’s home studio, with the plan of making a record, he quickly abandoned any hope of a collaboration. “There were nothing but girls everywhere and coke, bodyguards with guns, looking all evil…..We snorted some coke together and that was it.”

Paley continues: “He just wanted to do cocaine constantly. He just had no moderation. He had taste as a musician but he didn’t have taste in the way that he lived.” At one point, bandmate Rusty Allen heard Sly saying: “I think I have done too much shit, too much wrong, and I don’t think God will take me back.”

A disastrous engagement at Radio City Music Hall made clear how far Sly had fallen. John Rockwell’s write-up in the New York Times called it the “pop music rip-off of the year.”

The perpetrator was Sly and the Family Stone, which out of some well of egotism out of touch with recession realities booked itself into the 6,000-seat Radio City Music Hall for eight shows. Thursday’s opener attracted an official count of 1,100 and it looked smaller…..Kool and the Gang finished their set at 9:30. Sly came on a full hour later, played 45 minutes and that—apart from a few lonely boos—was it….

In the not‐too-distant past, Sly was one of the most exciting and significant forces in American pop music. But now he has taken to the stalest of rehashes of his greatest hits.

In the aftermath, bookings came to a halt. “I never quit the band,” vocalist Cynthia Robinson recalls. “I just stopped getting calls for gigs.”

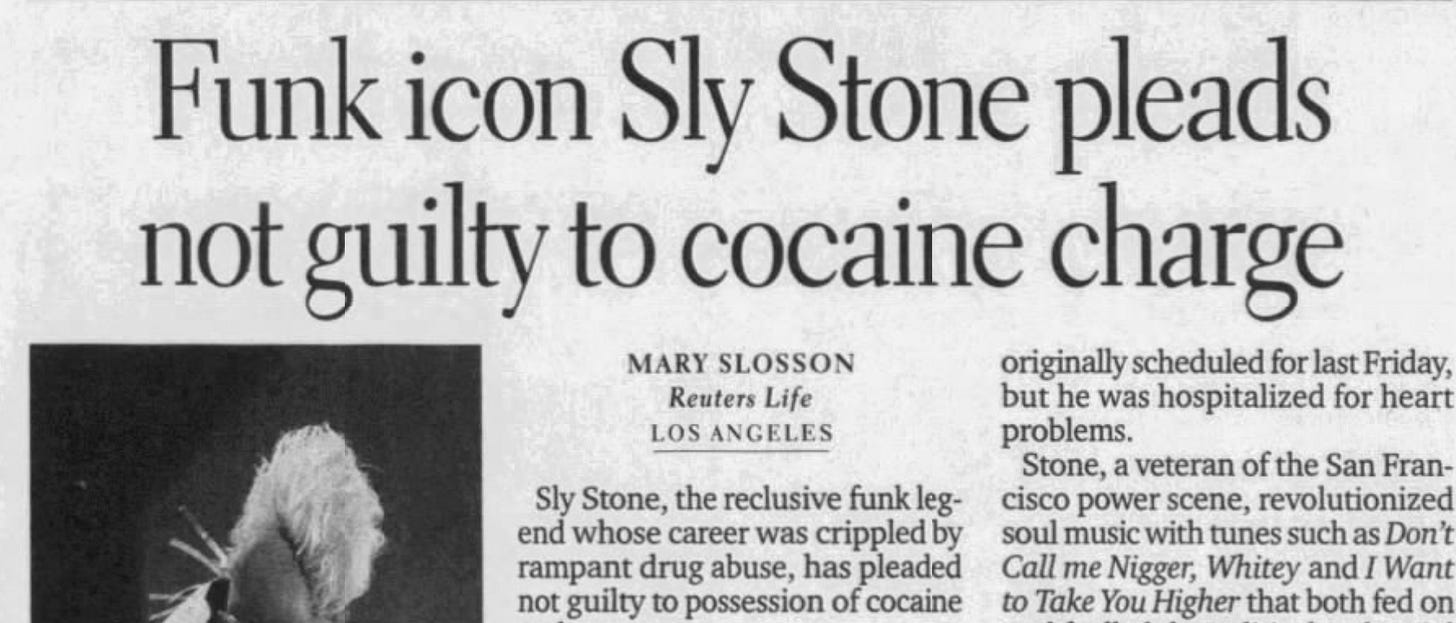

Stone launched a solo career—and would appear sporadically on stage or on record—but the glory days were over. And in 1983, he was arrested for cocaine possession. He spent six months in rehab, but without much to show for it. A nurse gave him advance notice of the urine tests, so he could make sure that he always passed.

The drugs continued. It was performing that Sly gave up.

When Sly and the Family Stone got inducted in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1993, fans wondered if he could show up for that gig. True to form, Sly arrived at the podium more than ten minutes late, after his bandmates had already given their acceptance speeches.

Robinson can be heard saying: “As usual.” Sly hardly spoke with the rest of the Family at the ceremony.

Once again, no comeback—just another comedown.

But Stone’s retirement from music didn’t put an end to the negative news stories. Most musicians would kill for a feature story in People magazine, but not the kind Sly Stone got in 1996. The headline announced “The Decline and Fall of Sly Stone. “

The article quoted his daughter, who hadn’t seen her father in years: “I don’t know why he treats me like that.” And his ex-wife: “Sly never grew out of drugs. He lost his backbone and destroyed his future.”

Even Stone’s landlord had dirt to dish—as People reported:

Last year, ex-landlord Chase Mellon III accused Stone of trashing the Beverly Hills mansion Mellon rented to him in 1993. Mellon says that he found bathrooms smeared with gold paint, marble floors blackened, windows broken and a gaunt Stone emerging from a guest house to say, “You’re spying on me.”

Sly responded with denials—and bragged that he had recently composed an album’s worth of material inspired by Miles Davis.

That album never appeared. And Stone, who had stopped performing in 1987, wouldn’t make music on stage again until the Grammy ceremony in 2006, when he briefly played the keyboard with a cast on his hand, and contributed some vocals that could barely be heard in the audience.

Could Sly make a comeback after three decades? For a moment it seemed possible. He told a writer for Vanity Fair that he had a huge backlog of unrecorded songs—”a library, like, a hundred and some songs, or maybe 200.”

When Sly Stone was booked at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 2007, his fans celebrated. But he only played for 20 minutes before walking off stage. In Nice, France Stone did the same. In Belgium, he at least offered an excuse—telling the audience that he realized, when he woke up that morning, that he was old and needed a break.

And then it got worse.

From that moment on, every time Stone appeared in the news, the story had nothing to do with making music.

For example, this account from the Associated Press in 2010.

The following year, Stone was in the news again.

The headlines increasingly mocked him, or expressed annoyance.

In 2012, record exec Clive Davis published his autobiography, and hardly mentioned his work with the superstar he had signed to a record deal back in 1967 But at one point Davis claims that he warned Whitney Houston not to be another Sly Stone, a musician who “destroyed his career.”

I never expected Stone to return from all this.

But in 2015, he finally showed up in the news with a positive story—the first in decades. Stone was awarded a $5 million settlement for unpaid royalties. But even this victory couldn’t fix his bigger battle against drugs and addiction.

His autobiography tells us that he has finally conquered drugs. And maybe he has.

In this memoir, Stone describes his repeated visits to the hospital. He didn’t get serious about quitting until the fourth time. “I knew what needed to happen,” he explains.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t like the drugs. I liked them. If it hadn’t been a choice between them and life, I might still be doing them. But it was and I’m not.”

That said, you won’t find many apologies in this book. Stone’s memoir is less a confession, and more a justification—mostly Sly being his “elf agin.”

It reminds me of the recent documentary about failed football legend Johnny Manziel. In both cases, the protagonists fail to grasp how many people they’ve disappointed, or how much they’ve betrayed their own talent.

The result is more a tale of survival than an inspiring recovery narrative. And so Sly Stone struggles to find a happy ending to his memoir. There’s been too much damage done along the way for that.

In the final pages, Stone serves up the most optimistic statement he can muster: “Human beings, we all come and go. Some of us have not gone yet.”

Let’s give him credit at least for that. Sly Stone is now 80. He survived despite doing almost everything possible not to.

As for the book—I’m not even sure it’s the best account of Stone’s career. I’d recommend Joel Selvin’s Sly and the Family Stone: An Oral History instead. But a memoir does create some sense of closure.

That said, I’d exchange this book for a few more records of Sly Stone at his peak—and especially that failed collaboration with Miles Davis. Or, even better, another book that could inspire people with similar addiction problems to get their life on track.

You won’t find much of that message in these pages. So once again, Sly Stone appears, only to leave us wanting more.

Good piece.

“I was buying shit left and right,” Stone admits, “including too many cars. At one point there were thirteen.”

The money came and went.

Lots of wasted potential. Imagine a reasonably sober Sly working with Miles Davis ...?

If only ...

Thank God the huge talent did reach the world, for a while, and the records are permanent.

Glad he is alive.

An illuminating read I didn’t realize I needed...