We're Living in a Scroll-and Swipe Doom Loop Culture

Here's how we escape it

Culture started out on scrolls. And now it has returned to scrolling (and swiping) as the dominant forms of transmission.

But, of course, those two types of scrolling could hardly be more different.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

A few days ago, a 16-meter scroll was unveiled at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In May 2022, this version of the Egyptian Book of the Dead got dug out of the ground in the Saqqara necropolis, part of the oldest surviving complex of stone buildings in human history.

This papyrus, like the surrounding pyramids, was made to last. It’s goal was nothing less than to guide the tomb inhabitant in the next life. A man named Ahmose is mentioned 260 times on the papyrus—so we can safely assume that the massive scroll was intended for his benefit.

And, in an odd sort of way, it did make him immortal.

That scroll is ridiculously long. But it’s only the second longest known ancient papyrus. The Harris Papyrus I in the British Museum is an extraordinary 41 meters in length. That’s 50 percent longer than an entire basketball court. Not even Steph Curry can hit shots from that distance.

I note that this amazing document was discovered in a tomb near Deir el-Medina—the same place where the love song and other lyrical forms of self-expression first appeared in human history. I’ve focused repeatedly on this village in my writings on the history of music—because it’s hardly known even among intellectuals and musicologists, and was the epicenter of arguably the most significant and long-lasting shift in the history of culture.

But scrolling today is very different.

The scrolling and swiping that drive today’s culture are the exact opposite of those imposing ancient papyri. Web platforms have implemented scrolling as an interface because it’s the fastest possible way of accessing new stimuli.

These newfangled digital scrolls are not made to last. They’re supposed to disappear—and the faster the better. We measure their duration in seconds.

But they’re everywhere. Not long ago, people talked about living in a push-button society. But those buttons are disappearing. Today we live in a scroll-and-swipe culture.

Nowadays people find music by scrolling. They follow the news by scrolling. They even decide who to date and marry by scrolling.

The medium is the message, as Marshall McLuhan announced 59 years ago. And that’s eerily true today—maybe more than ever.

But why is the scroll-and-swipe medium so popular?

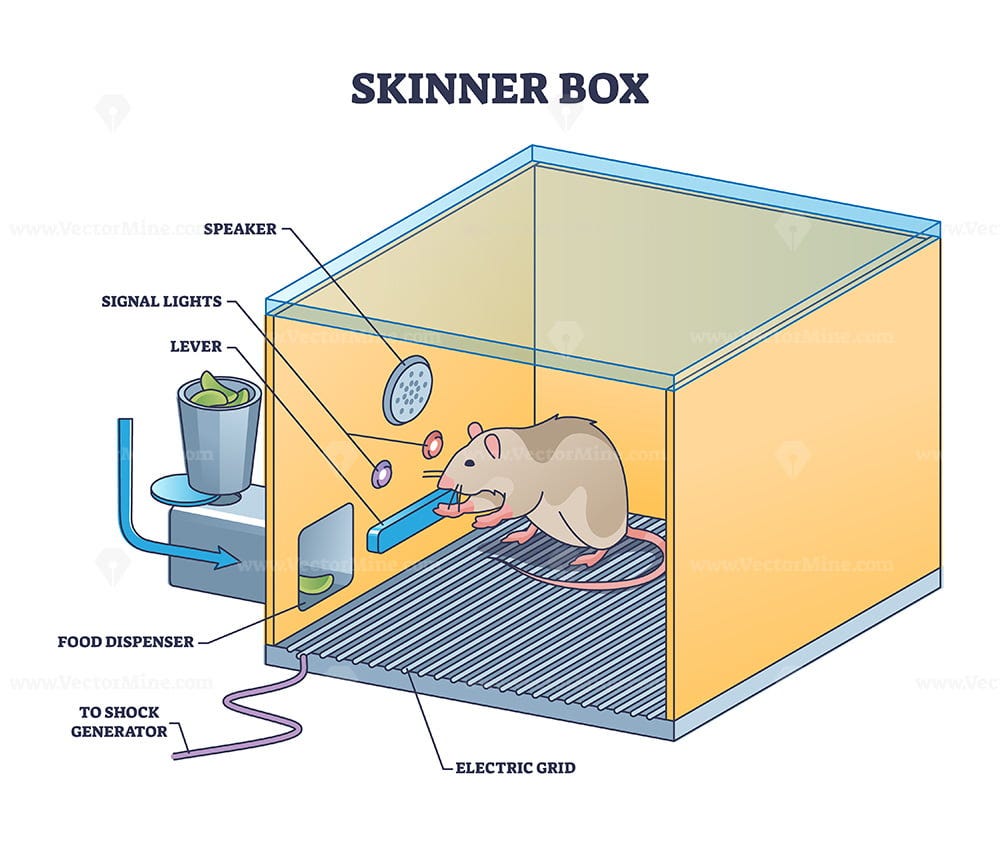

The psychological theory behind scrolling is known as intermittent reinforcement. Behaviorist B.F. Skinner proved back in 1956 that rats could be manipulated more easily if rewards and punishments were sporadic and unpredictable.

If you want rats to press a lever, you give them rewards—but not every time. This was Skinner’s brilliant insight, and he demonstrated it in numerous experiments.

You might think that always rewarding the desired action—known as continuous reinforcement—would maximize the targeted behavior pattern. But that’s not true. Skinner showed that variable rewards have a much more powerful impact on rats. And if you really want to keep rats pressing a lever, the rewards should be distributed in a random manner with no apparent pattern.

By pure coincidence, the Las Vegas Strip was taking off at the very same moment that Skinner was doing his breakthrough research. You might say they were both proving the same thing—one with rats, the other with slot machines.

Our body chemistry also contributes to the addictive power of scrolling and swiping. Those dopamine flows that create addictions are more powerful when they are intermittent. Unpredictability adds to our pleasure.

I am not a fan of B.F. Skinner. But that’s not because his experiments don’t work. I will admit that they produce the desired results, at least within certain limits (that’s important and I’ll return to these limits later). My opposition is based entirely on my views of how we should treat people—it’s ethically wrong to manipulate them like rats in a Skinner Box.

When I studied music therapy in preparation for writing my book Healing Songs (2006), I was horrified at how deeply Skinner’s behaviorism had permeated academic writing on the subject. I encountered it again and again, and in ways that deeply disturbed me.

I remember reading a study about how music could be used to help juvenile delinquents. That seemed promising to me—music ought to be part of rehabilitative programs. But the psychologist in charge was obsessed with the idea that incarcerated teens would practice the guitar more often if he gave them cigarettes every time they played the instrument.

The experiment worked—but of course it did. These behaviorist experiments always work in the short term. And if cigarettes don’t do the trick, we just need to substitute chocolate or cocaine or crystal meth. The problem with these initiatives is not that they don’t change behavior, but they only control the surface action, while typically destroying people’s characters and values in the process.

In other words, it’s better not to learn the guitar if you’re only doing it to get cigarettes. That should be obvious.

On the other hand, if you’re running a Las Vegas casino, you need to pay close attention to Skinnerian psychology. The pit boss doesn’t care about your longterm psychological health, just the daily cash flow. That’s why the entire gambling business is built on intermittent reinforcement. And, once again, it works like a charm—at least on the surface level of manipulating behavior in the short term.

The gambling business is enormous—more than $50 billion in the US alone. And it’s growing at a dizzying pace, especially because of looser regulation and the proliferation of online options.

Wouldn’t it be great if we could grow our music, arts & culture infrastructure as fast as our gambling businesses?

Well, watch out what you ask for. Because that’s exactly what the leading web platforms are trying to do. And, like those pit bosses, they rely on intermittent reinforcement.

The most obvious example is TikTok. There’s a reason why it’s the most downloaded app in the US.

It’s like a Skinner Box on your phone. You will keep pressing the lever. Once you start using it, you will spend more time with TikTok than with family or friends.

One user recently commented:

“Seeing that my screen time daily average for TikTok is two hours and 33 minutes is not a surprise. Once I get on the app, I cannot stop. The shortness of the videos is probably what makes me continue scrolling. Although, how I have a 13-hour weekly average on TikTok definitely concerns me.”

Another user admitted that her daily average on TikTok was 5 hours and 54 minutes. That’s almost 40% of her waking life.

But the swipe-and-scroll culture not only eats up time. It also changes our relationship to time.

I’ve often mocked this platform in the past for its bite-sized videos—the most popular length is 21 to 34 seconds. But the sad truth is that these numbers actually overstate the level of engagement. Most users scroll rapidly through their videos, and don’t wait for the end—even if it’s just a few seconds away.

The situation is so bad that TikTok has talked about a 6-second goal to its advertisers. That’s a big deal because so many users swipe before that point. When 3 million people watched a 6-second Ryanair ad on the platform, marketeers shouted hosannas from the rooftops. This was a huge victory.

And in a Skinner Box, it is a big win. It’s not easy to get rats to wait six seconds to push the lever.

I focus on TikTok, but every major social media outlet is moving in the same direction. Facebook launched its Reels globally last year. Around that same time, Instagram copied TikTok’s full-screen scrolling interface. A few months later, Twitter did the same. YouTube also has its ‘Shorts’ option. And now Spotify—which has such huge impact on our music culture—also aims to be more like TikTok.

In other words, the web is turning into the online equivalent of the Las Vegas strip. As soon as you leave one casino-like platform offering intermittent reinforcement, you walk into another. The games are almost the same everywhere—with the same loser’s payout—but you have an illusion of choice.

What happens when an entire culture shifts to intermittent reinforcement models?

Everything gets faster. That’s why TikTok creators are speeding up their songs and visuals.

Everything gets shorter. That’s why song duration is shrinking—the 3-minute pop song has been replaced by the 2-minute pop song.

Everything new soon seems old. Trends come and go as users churn through novelties.

Everything gets dumber. Hey, just look around you.

Do we want this? It doesn’t really matter, because we’re getting this.

But there’s the bigger question: How will this story end?

You might think I’m pessimistic. But I’m not.

And, unlike some politicians, I don’t think the answer is censoring TikTok. They are only a small part of the scroll-and-swipe doom loop. If we get rid of them, the core audience just shifts to another Skinner Box, run by Mark Zuckerberg or some other technocrat.

But if censorship isn’t the answer, what is?

First let me share some good news: When I studied behavioral psychology, I came to the conclusion that human beings really aren’t like rats. In the short term, you can manipulate them with Skinnerian systems of reinforcement. But over the long run, humans will do something the rats never do—they rebel.

Sure, if you put people in one of those rat mazes, they will figure out how to run through it and find their rewards. But eventually the more independent individuals will decide to destroy the maze.

People will do this even if they kill themselves in the process. They have this strange little thing called human dignity—and they actually believe it exists. The behavioral psychologists can’t understand this because such metaphysical notions don’t fit into their data-driven world view. But that doesn’t really matter, people believe this stuff—they have a sense of their self worth even when put in a box or a maze. They feel it in their hearts and souls, and it actually gets stronger in the face of adversity.

Some individuals might run the maze, but a meaningful number will resist—and they do so as a matter of principle. (That’s another word you won’t hear from the behaviorists. Personal values and core principles don’t show up in their test models—because they can’t be charted. And the Skinnerieans make the same mistake that undermines all radical empiricists: They assume that things that can’t be measured don’t exist—which is a very foolish and dangerous error.)

I believe that most people put their values ahead of those carefully constructed intermittent reinforcement rewards.

For example, those slot machines in Las Vegas are addictive, but data shows that 74% of people never gamble. That’s a useful ratio to keep in mind. You can get a quarter of the population to act like a rat in a box, and if your goal is to make money, that’s a sufficiently large market. But it’s not a majority of the public or even a large minority.

That’s why the swipe-and-scroll culture will soon reach its saturation point. You don’t need to outlaw it. You don’t need to censor it.

And you certainly don’t need to imitate it. That’s because the most powerful response is to do the exact opposite—namely, offer deeper and richer entry points into music, arts, and other cultural idioms.

And we do this without apologies, because most people crave something more enriching than a quick dose of dopamine from their handheld Skinner Box. Once they’ve tasted the real thing, a meaningful number of them—a decisive majority, in my opinion—will refuse to give up the riches of their music, books, movies, museums, and other repositories of glory and genius.

They will walk away willingly (and happily) from those six-second jolts.

If you’ve reached this far in my article, you already know it. The people seeking instant gratification would never get to this point.

By the way, that’s why Substack is flourishing. That’s why long podcasts are so popular. That’s why the book business is rebounding. That’s why the classical music audience is growing again. That’s why most of the award-winning movies in the last year were more than two hours long.

In case you weren’t counting the minutes, here’s the rundown:

This group of Best Picture nominees is also the first since 2020 to include no films under 100 minutes in length. 88 minutes separate the longest and shortest films in the bunch, and they all have an average running time of 144 minutes, which is 18 minutes higher than the category’s all-time mean.

Do you see what’s going on here? A huge number of people are moving in the exact opposite direction as the TikTok dopamine addicts. They’re creating an alternative culture that’s smarter and better. We’re part of it. And our numbers are growing, despite everything you’ve heard to the contrary.

The culture wants and needs this. A substantial and growing audience actually craves this kind of immersive artistic experience. They’re tired of scrolling and swiping.

Even some of the rats in the box will figure this out. The folks running the huge web platforms are going to be surprised. My view of behaviorist experiments is that the longer they go on, the worse the results. The longer the time frame, the more likely that humans will rebel against any demeaning system—and will do so no matter the personal cost.

It would be great if those rich and powerful people and institutions supported us in our alternative culture. They might accelerate the turnaround. But we’re not waiting for them.

Let them sit on the sidelines, and swipe away the hours. That said, I suspect that even the technocrats will want to join us, sooner or later. Because if it’s demeaning to run around in a rat maze, it’s far more undignified to be the person managing the maze. Even if you’re a rich Silicon Valley CEO, you will figure that out sooner or later.

Bravo! I have been waiting for something like this for a while! I am so happy there are a few people who understand these aspects to our human nature. Onward!

In the future, we'll all pay attention for at least fifteen minutes.