Unpacking My Library

I usually write books, but my biggest project in 2021 was moving them—and it's tougher than it looks

Writing about how to unpack a library is a little absurd. The cultural critic Walter Benjamin proved that in his 1931 essay, literally entitled “Unpacking My Library”—which is both a classic, and a wee bit ridiculous.

The absurdity in Benjamin’s case stems from his reputation as a exponent (and perhaps the leading exponent) of Marxist literary criticism. A true follower of Marx ought to give up all private property—perhaps with even more purity than in the Gospel injunction—but, at a minimum, really shouldn’t be a collector or hoarder of objects, whether books or anything else.

“How did I get so many books? And why do I bring them with me from place to place? Isn’t it all too much?”

Benjamin found himself drawn to Marx after reading History and Class Consciousness (1923) by Georg Lukács (perhaps the only person more preeminent than Benjamin in the cultish world of Marxist lit-crit), and even made a trip to the Soviet Union during the winter of 1926-1927. His most famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935) is rich with implication even in today’s strange world of non-fungible tokens and digital curation. But it’s often read as a celebration of mass-produced culture, in which unique objects are displaced by copies and reproductions. Who needs a painting, if you can check out an art book from the library? And who needs a book when you can download the text online?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported newsletter. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. Those who want to support my work are encouraged to take out a paid subscription.

Keep that in mind as you read Benjamin’s description of his books, which begins: “I am unpacking my library. Yes, I am.” And then continues with the passion of a wine connoisseur or even an ardent lover. He writes, in long ecstatic sentences, which I’ll mostly spare you—but here’s a tiny taste:

“I must ask you to join me in the disorder of crates that have been wrenched open, the air saturated with the dust of wood, the floor covered with torn paper, to join me among piles of volumes that are seeing daylight again after two years of darkness, so that you may be ready to share with me a bit of the mood—it is certainly not an elegiac mood but, rather, one of anticipation which these books arouse in a genuine collector. For such a man is speaking to you, and on closer scrutiny he proves to be speaking only about himself. . . .”

And that’s just a start.

In fact, Benjamin was more a failed lover at this juncture. His marriage had recently ended, and he needed to move some two thousand books to a small apartment. He was approaching forty, and—true to his dialectical materialist worldview—was almost without property. But the books provided an anchor and a semblance of stability in a world that rarely gave him much support.

He would be dead before the end of the decade, killed by his own hand while trying to escape the Nazi regime and get to the United States. He made it as far as Spain, where authorities told him he would be sent back to France, under German occupation at the time. Fearing the worst, Benjamin took an overdose of morphine. The next day, the Spaniards relented, and allowed the rest of his traveling party to proceed to Portugal—but perhaps only because of their shock at his suicide.

So I read Benjamin’s account of his library with indulgence. The books provided him with a fleeting sense of a stable home that the surrounding sociopolitical turmoil never allowed him. Perhaps we can all relate to that in some degree.

I don’t share Benjamin’s antipathy to private property. But I have tried to lead a simple life, unencumbered by too many things—at least, that’s what I tell myself (despite, I’ll admit, more than a little evidence to the contrary)—so my joy in unpacking my library is also somewhat absurd. How did I get so many books? And why do I bring them with me from place to place? Isn’t it all too much?

The first question people ask me—especially movers who have to convey these bad boys from place to place—is a simple one: How many books do you own?

What can I say in my meager defense?

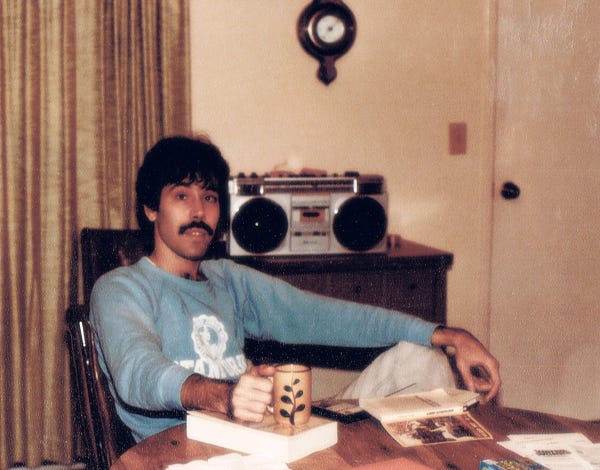

Let me take a stab at it. Can I approach the bench, your honor? Around age 20, when I was a poor student under the tightest of budgets, I promised myself one thing. If I ever got out of that beggarly state, I would indulge myself in two areas—books and music. I’m willing to cut back elsewhere, but those must be exceptions.

But I have another justification for my overabundance of books, perhaps even more persuasive than a promise to my younger self. I’ve often lived in places far from world class research libraries, and this has demanded that I keep most of what I need near at hand. I wrote much of The History of Jazz in Napa, where there are plenty of wineries around, but not much in the way of a decent music library. Most of my Work Songs and Healing Songs books were written near a beach south of San Diego, and I sometimes had to make a long drive to the UCLA Library or undergo some other painful SoCal commute just to finalize a footnote. At a certain point, I decided that I needed to become a book collector just to meet the requirements of being a scholar.

So many decades later, I’m living with the results of that indulgence. And it takes up a whole lot of space.

The first question people ask me—especially movers who have to convey these bad boys from place to place—is a simple one: How many books do you own?

Italics fail to convey the tone of voice, which is perhaps all the better. There’s something downright suspicious about anyone with so damn many books, and judging by their inflections and grimaces I’m less a potential customer than a suspect at a crime scene.

I half expect them to turn, with a sweeping gesture, to the crammed shelves and declare: This will all have to go into evidence.

They’re surprised when I can’t answer that modest query. But is that really so odd? I read them, yes. I own them, yes. But it would take days to count them. So I honestly have no idea how many books I own. For the purposes of placating real estate agents and movers, I tell them that I possess between five thousand and ten thousand volumes. But that’s just a guess.

The logistics of moving these objects of shame may be of interest to some readers—either for the practical relocation tips I can share, or perhaps simply to savor the depths of my deplorable obsession. So I will tell the whole tale of how I moved my dragon’s hoard of dusty tomes.

The first challenge was to find a home that could accommodate all of these volumes. Our plan was to move to the Austin area, our preferred destination, and I hoped (perhaps irrationally) to find a house that already had shelves in place for my sprawling collection. I labored in vain with the real estate listing search engines, where the keyword “library” doesn’t get many hits. And when I found something promising, the price tag tended to be somewhat outside my budget, as with this home library at a property listed at $5.5 million.

Nope, that wasn’t going to work—I’d need a dragon’s hoard of gold to go down that path. I clearly needed to think more creatively.

I started looking for homes with large open spaces that might be converted into a genuine library. Eventually we found a charming place near Lake Travis, a half-hour from downtown Austin, with an open upstairs area that looked like this on the listing.

Okay, it’s not as awe-inspiring as a millionaire’s mansion, but it had potential. Even better there was a large room adjacent to it that could also accommodate additional shelves, a kind of spillover or overflow area. The bottom line: I could have a two-room upstairs library, in addition to the downstairs areas where bookcases could blend in with the decor.

For example, I could fit additional books downstairs behind the piano, or in other rooms.

The first step—and I can’t emphasize this too much for anyone who might be considering a similar move—was to hire a structural engineer. Putting this many books in an upstairs area is just asking for trouble. Books are heavy. Don’t get fooled by the thin paper pages—if you put enough of those pages together, they weigh more like tree trunks. And when you accumulate a whole forest of them in a small enclosed space, they can cause damage. The story of the sinking college library may just be an urban legend, but even worse things have happened because of too many books.

After getting the go-ahead from the structural engineer and managing to purchase the property (not easy in the post-pandemic Austin housing market, but I’ll have to save that story for another occasion), my wife worked with designer Rhonda Miller in coming up with an actual library conversion plan.

This was the stunning plan Rhonda came up with:

While she made progress implementing this vision, I had to figure out a way to move my books. It soon became clear that I needed to stage the move in several installments, with a whole week and crew dedicated just to transporting books—furniture and other possessions would have to wait. At my wife’s suggestion, we also engaged a skilled relocation problem-solver, Pamela McCarty, and this proved to be a very smart move. She had done work previously for the Getty collection, and was so thorough and dedicated during the entire course of my move that I wholeheartedly recommend her to others who are thinking of moving a library. (She can fly out to any location to manage a project.)

Pamela handled the shelving of all my non-music books, which went downstairs. But the music books I needed to organize myself, because I had a quirky plan for arranging them that involved a mix of genre, geography, function, and chronology. For example books on early music would go in a separate area, sequenced by chronology—starting with hunters and gatherers in caves, and ending up at the Renaissance.

But for later periods, the books would get organized by genres (country, rock, blues, etc.) or function (work songs, sea shanties, healing songs, etc.) or geography (Asian music, African music, Latin American music, etc.). Finally my jazz books—the largest single group in the collection—would get organized into subsections (biographies, criticism, regional styles, reference works, etc.).

I’m sure professional librarians would hate my plan. Many people told me to stick with the Dewey Decimal system. But I know full well that Mr. Dewey’s approach simply won’t work for my needs. The books in my home library need to match the outlines of my past, present and future research projects.

It took roughly four days for me to unpack and organize my music books. Here’s what the main room of my home library now looks like.

And, for a closer look at a single sections, here’s how I’ve organized my blues books.

This is the first time in decades that my books have been arranged in a logical, accessible way. I simply never had the space for it before. I ought to rhapsodize now in the style of Walter Benjamin. After all, something I’ve been hoping to achieve for many, many years is now accomplished. But—phew!—my back and arms are sore—and instead I think I’ll just take a break.

Wow Ted! Your book fetish is heavy. I love the open library table, so much creative potential.

This. Is. Glorious.