The World Was Flat. Now It's Flattened

The state of the culture, 2025

This time every year, I deliver a “State of the Culture” speech.

I do it in my home office—it’s quieter here. Nobody interrupts me. I don’t even have to shave.

Related Article from The Honest Broker:

Okay, it’s not ideal There’s no audience—so I have to imagine applause and TV cameras. There’s no media coverage (unless I create it myself). There are no special guests.

Even so, the State of the Culture is still more interesting than a State of the Union speech, filled with boasts and political grandstanding and pre-fab talking points.

That’s because culture is the ultimate source of everything happening now. Even political change is the result of cultural shifts.

People are starting to figure that out.

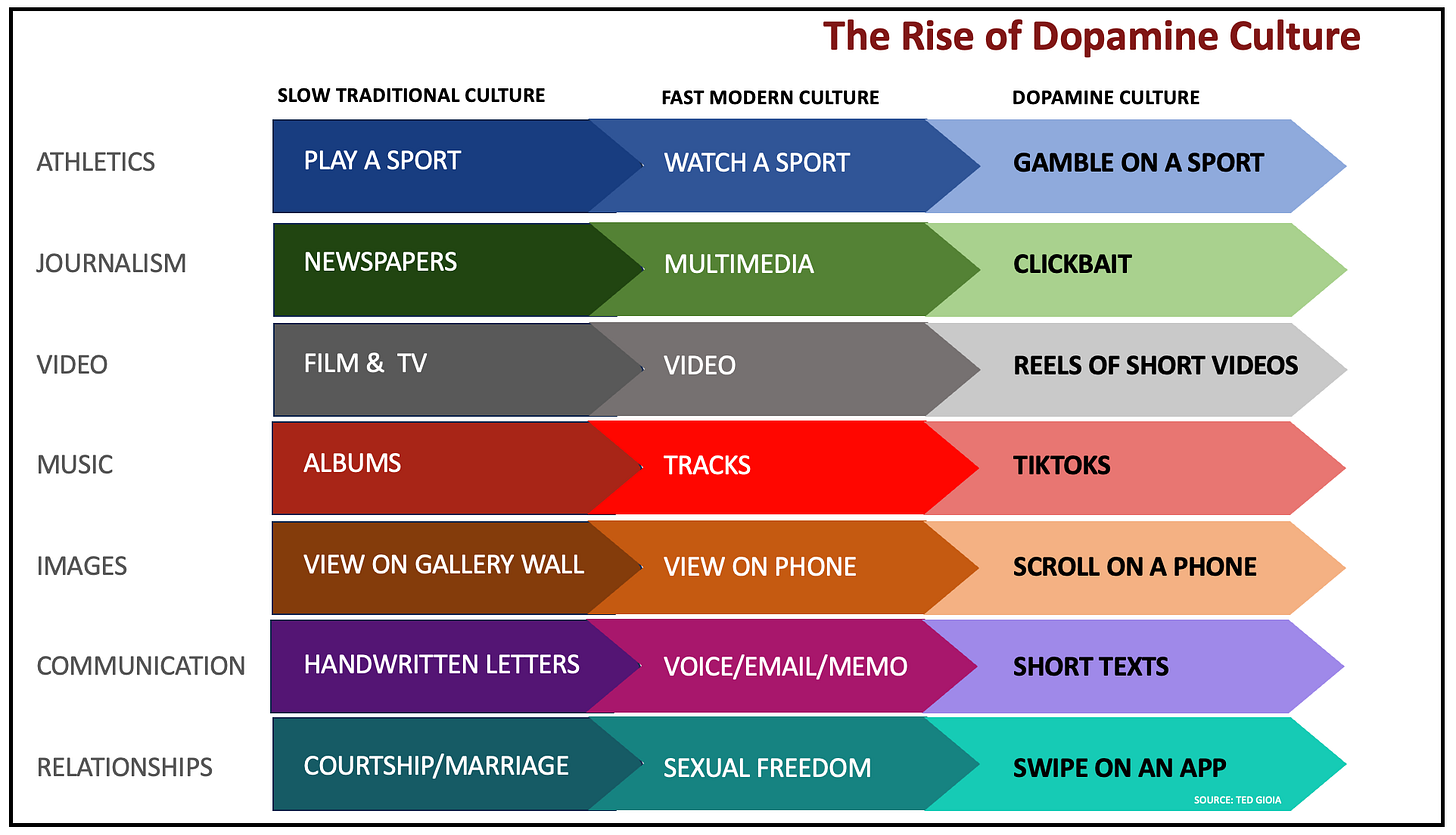

Last year I shared this homemade graphic in my “State of the Culture” article—and it reached more people than anything I’ve ever published here.

Even in an election year, this seemed to capture something significant beyond the reach of political discourse.

But what about today?

The State of the Culture, 2025

So remember the first rule: The culture always changes first. And then everything else adapts to it.

That’s why teens plugged into the most lowbrow culture often grasp the new reality long before elites figure it out. This was true 50 years ago, and it’s still true today.

So that’s our second rule: If you want to understand the emerging culture, look at the lives of teens and twenty-somethings—and especially their digital lives. (In some cases those are their only lives.)

The web has changed a lot in recent years, hasn’t it? Not long ago, the Internet was loose and relaxed. It was free and easy. It was fun. There wasn’t even an app store.

We made our own rules.

The web had removed all obstacles and boundaries. I could reach out to people all over the world.

The Internet, in those primitive days, put me back in touch with classmates from my youth. It reconnected me with friends I’d made during my many trips overseas. It strengthened my ties with relatives near and far. I even made new friends online.

It felt liberating. It felt empowering.

But it also helped my professional life. I had regular exchanges with writers and musicians in various cities and countries—without leaving the comfort of my home.

I made new connections. I opened new doors.

And this didn’t just happen to me. It happened to everybody.

“The world is flat,” declared journalist Thomas Friedman. All the barriers were gone—we were all operating on the same level. It felt like some imaginary Berlin Wall had fallen.

That culture of flatness changed everything. Ideas spread faster. Commerce moved more easily. Every day I encountered something new from some place far away.

But then it changed.

Twenty years ago, the culture was flat. Today it’s flattened.

“Corporations didn’t intend to make the culture stagnant and boring. All they really want is to impose standardization and predictability—because it’s more profitable.”

I still participate in many web platforms—I need to do it for my vocation. (But do I really? I’ve started to wonder.) But now they feel constraining.

Even worse, they now all feel the same.

Instead of connecting with people all over the world, I now get “streaming content” 24/7.

Facebook no longer wants me stay in touch with friends overseas, or former classmates, or distant relatives. Instead it serves up memes and stupid short videos.

And they are the exact same memes and videos playing non-stop on TikTok—and Instagram, Twitter, Threads, Bluesky, YouTube shorts, etc.

Every big web platform feels the exact same.

That whole rich tapestry of my friends and family and colleagues has been replaced by the most shallow and flattened digital fluff. And this feeling of flattening is intensified by the lack of context or community.

The only ruling principle is the total absence of purpose or seriousness.

The platforms aggravate this problem further by making it difficult to leave. Links are censored. Intelligence is punished by the dictatorship of the algorithms. Every exit is blocked, and all paths lead to the endless scroll.

All this should be illegal. But somehow it isn’t.

Do you remember rule two above? It said: Look to the teens, and their digital lives.

When you do that, you see immediately that they are the main victims here. This flattened culture is all they have ever known. It’s now the landscape of their inner lives.

Many of these youngsters lack the skills and tools required to escape. So this flattened world is really their prison—and the billionaire wardens (Mr. Z and Mr. M and all the rest), who get rich from their brokenness, want them held in their digital chains forever.

In all fairness, let me say that the corporations didn’t intend to make the culture stagnant and boring. They didn’t intend to cause teen depression, suicidal impulses, anxiety, self-harm, and all the rest.

All they really wanted was to impose standardization and predictability. That’s what businesses always want—because it’s more profitable.

But corporate standardization always brings negative unintended effects:

It destroyed artisans and craftsmanship—because uniformity was more profitable.

It eliminated indie businesses from your community—because uniformity was more profitable.

It made every mall look the same—because uniformity was more profitable.

It made architecture boring, turning everything into a box—because uniformity was more profitable.

It banished beauty from everyday life—because uniformity was more profitable.

You can even see this quest for uniformity and standardization in their corporate symbols. Every logo now looks exactly the same.

But here’s the problem. With the rise of social media and other apps, corporations are now trying to impose standardization on people.

That means you and me.

Everything we do, from dating via apps to getting a meal from DoorDash to communicating with friends on Facebook, must be handled in a uniform, standardized way. That’s because—yes, you guessed it—it’s more profitable that way.

This is how people get flattened.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

Our new lives will be as shallow and predictable as the spinning wheels on a slot machine. And that’s by design—the web platforms study what happens in casinos and incorporate what they’ve learned in their apps.

All this frenetic activity is supposed to distract us from the larger threat—which nobody talks about.

I’m referring to the power reversal on the web.

The early web empowered the user. And the very name “web” was revealing—each us could create a unique network of relationships and connections all over the globe.

It was our web.

But the standardization and bunkerization of web platforms has put power in the hands of the digital overseers. We are now caught in their web—and they are the spiders.

In this kind of culture, we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that the richest man in the world controls two-thirds of all the satellites surrounding the Earth. Our information network is actually his information network.

He really does own his own web. And it surrounds every one of us.

You couldn’t find a more suitable metaphor for a flattened world. But this isn’t a metaphor—it’s just a plain fact.

You certainly won’t learn about this in a State of the Union speech. If you want to grasp what a flattened world feels like, you must look at the culture. You must look at the teens and twenty-somethings.

They will tell you more than any politician.

“Are we all beginning to have the same taste?” asks critic Rebecca Nicholson—complaining about her inescapable sense of repetition and sameness pervading music, TV shows, films, and everything else.

What if, guided by some invisible hand, we were all converging on the same likes and dislikes? What if taste was no longer a question of making finer and finer distinctions, but of being nudged towards uniformity?

The only thing I disagree with here is the idea of an invisible hand.

The people promoting this flattening may want to hide behind an invisibility cloak, but they are easy enough to identify.

Just put together a list of the people who run the largest web platforms, entertainment companies, and media empires. You will come up with a list of 20 or 30 names—and they have their quite visible hands and fingerprints on everything.

They push the content. They build the devices. They own the satellites. They run the platforms. They swallow up the cash flow.

It’s their heavy weight that is flattening the rest of us.

If we could just get out from under it, we might be able to breath easier. We could reconnect with all those friends and family members who got replaced by memes and videos.

We could regain control of our lives as creative agents operating in a real world instead of passive consumers of flattened culture in an artificial screen simulacrum.

Doesn’t all this make you yearn for a rebel?

When you watch this happen, don’t you crave a return of indie culture? Don’t you hope for a resistance movement? Don’t you want to see a backlash to uniformity and standardization?

Of course you do. And you’re not alone.

Do a favor for a friend. Gift subscriptions to The Honest Broker are now available.

That’s the good news in my State of the Culture speech.

Maybe those 20-30 ultra-rich bosses at the dominant web and media companies want everything (and everybody!) standardized and under their control. But hundreds of millions of people are now starting to push back.

So we really have two cultures.

The culture of stagnation is huge. It runs the largest businesses in the world. It is promoted by the richest people in the world. It is loud and pushy, and dominates the news cycle every day.

But there’s another culture that has only recently emerged from hiding. Or you might call it a counterculture or an underground movement.

In an earlier day, it was just called the Resistance. That’s still a good name, by the way.

It’s easy to miss, because it doesn’t have a trillion dollars of investment capital at its disposal.

But it does have the allegiance of the people—more so with each passing month. And history tells us that people eventually determine all shifts in culture.

If you work in the culture business, that’s worth remembering. Or even if you work in politics or on main street.

And if you forget, you will soon get an unpleasant reminder. And it just might happen before this time next year, when another ‘State of the Culture’ address is due.

I expect I’ll have a very different message to share next time around—a message about a culture that refuses to stay flattened.

Yes, a lot can happen in twelve months. We saw that last year. But there might be even more fireworks in the days ahead.

"What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture." This from Neil Postman in Amusing Ourselves to Death from 1985 is extraordinarliy prescient. We 'are' being deprived of information and reduced to dull passivity in a sea of boring irrelevance. I see it in the students I teach and I see, feel is a better word, it in myself. Agency slowly draining away. Scrolling for the next self-righteous dopamine hit. But the world is still out there waiting for us in all its craziness and wonder.

All you have to do is watch the epic scene from the 1976 film Network where Ned Beatty’s character explains how the world really works. This film was 50 years ahead of its time.

“There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM and ITT and AT&T and DuPont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today. What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state? Karl Marx? They get out their linear programming charts, statistical decision theories, minimax solutions, and compute the price-cost probabilities of their transactions and investments, just like we do. We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr. Beale. The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable by-laws of business. The world is a business, Mr. Beale. It has been since man crawled out of the slime. And our children will live, Mr. Beale, to see that perfect world in which there's no war or famine, oppression or brutality. One vast and ecumenical holding company, for whom all men will work to serve a common profit, in which all men will hold a share of stock. All necessities provided, all anxieties tranquilized, all boredom amused.”