The Tragic Final Days of Billie Holiday

There was a side of Billie Holiday fans never saw. And the pop culture narratives about her ignore it—for the sad, simple reason that positive details about Lady Day (as she was called) don’t fit the preferred tabloid storyline. But at home, the famous jazz singer would put on a comfortable dressing gown, turn on the radio, and relax by knitting or crocheting. Sometimes she would bring knitting needles on the road with her—although it’s another kind of needle that got most of the media coverage.

She was devoted to her dog—perhaps not surprising for someone who demanded absolute loyalty from those around her, and so seldom got it. (“She was extremely possessive,” Holiday’s longtime pianist Carl Drinkard explained. “Anybody who belonged to her, belonged strictly to her.”) Over the years, there was Chiquita, Pepe, and Mister to share her domestic life—and no rhythm section or lovers would ever prove as reliable. Holiday sometimes spoke of wanting children, but Holiday’s pets were the main outlet for maternal affection she couldn’t give elsewhere. One musician even saw her put a diaper on her dog and feed it from a bottle

Addiction destroyed her, but she dreamed of something better. “I’m so sick of this shit,” she told guitarist John Collins a few months before her death. “I’ve tried everything. I’ve tried to kick the habit, and I can’t kick it.”

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported newsletter. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. The best way to support my work is by taking out a paid subscription.

Substance abuse problems are not uncommon in the entertainment world, although most of them are kept hidden from view. But with Billie Holiday, her indiscretions were headline stories. And if the reality wasn’t good enough, people invented even more extreme tales. Drinkard, who spent many long months with Lady Day on the road, was amazed at the lies circulating about her—the East Coast people who related some bit of gossip would claim it happened on the West Coast, while in California the incident allegedly took place back East. They didn’t realize that Drinkard had accompanied her in both settings, and knew the accounts of each side were often pure invention.

But the government authorities were the most suspicious of all. A few days after Holiday returned from her tour of Europe in January 1959, a US Customs official phoned the singer—announcing that she had violated a new law requiring narcotics criminals such as her to notify the government of all trips to and from the United States. This law, which Holiday knew nothing about, applied retroactively even to narcotics convictions in the distant past. Holiday was so fearful of the consequences she wouldn’t even tell her agent—knowing how her reputation was already making it difficult to get bookings. So she traveled secretly to a federal building and, after submitting to an interrogation by three federal investigators, was told there would be no criminal prosecution this time.

A few weeks later, Holiday’s closest musical partner, saxophonist Lester Young, died just hours after returning from a Paris engagement. He was 49 years old—and, like Holiday, worn out from alcohol abuse. Billie Holiday was almost six years younger than Young, but she had been diagnosed with cirrhosis, and would only survive him by four months. Two years earlier, they had made a brief appearance on television for a CBS show as part of an all-star band, and their musical chemistry performing the song “Fine and Mellow” ranks as my most cherished moment of jazz captured on film. But this would be the last moment of glory for the duo, their greatness destined for the ages, but not for the immediate future.

Savor this musical interlude—because the rest of the story will have nothing quite so inspiring.

At Young’s funeral, Holiday was heard predicting her own demise. Sylvia Sims, who encountered Billie Holiday on the street around this time, recalled her saying: “Baby, everyone I love is dead—and you dead and I’m dead.” When Sims replied: “You’re alive and I’m alive,” Holiday replied: “You mean it?”

She continued to work, and sometimes gigs went well. A week in Boston at Storyville in April was well received. But when Leonard Feather met her backstage in Greenwich Village in May, he was shocked at her appearance—Holiday had lost twenty pounds since the last time he had seen her, just a few weeks before. She was so fragile that evening, she needed help getting to the stage, and could only deliver two songs before giving up, too weak to continue.

That would be Billie Holiday’s final public appearance.

Despite the urging of friends, she refused to check into a hospital. But on the last day of May, she collapsed while cooking at home, and fell into a coma. An ambulance brought her to Knickerbocker Hospital, where she lay on a stretcher in the emergency room for an hour before getting seen. The official diagnosis was “drug addiction and alcoholism”—although it was actually a case of cardiac arrest and liver damage—and Holiday was accordingly refused admission. A second ambulance trip brought her to Metropolitan Hospital in Harlem, where she again waited unattended.

Holiday was eventually given care and put in an oxygen tent. Over the next 72 hours, she showed no signs of narcotics withdrawal, and actually began recovering. In the ensuing days, Holiday responded to treatment, gaining weight, and even envisioning a return home. But the police, hoping for a newsworthy arrest, showed up on June 12 to conduct a search at Metropolitan Hospital, and allegedly found a small tinfoil wrapper containing heroin—possibly a plant, or a gift from a well-meaning but misguided visitor. Authorities charged Billie Holiday with narcotics possession, and although she was still too weak to be taken into custody, police guards were assigned duty outside her hospital room.

There was heavy irony here. Just a few days before, the mayor’s office had announced a new program that would address drug addiction as a medical problem, and not a target for punitive measures. But until a court eventually ordered their removal, law enforcement officers supervised every step in Holiday’s attempt to recover from what would prove her final illness. Even at this late stage, the District Attorney enlisted Holiday’s nurse as a witness for the prosecution, and tried to schedule an arraignment at the patient’s hospital bed.

Such was Billie Holiday’s tragic situation in her final days. If she ever left the hospital, she would need to face a grand jury. Her opportunities to perform and support herself would continue to decline in the face of the public shaming of a jazz star. And she would need to stop using alcohol and the other substances that had brought her so close to death—not to please the police, but merely to ensure her survival.

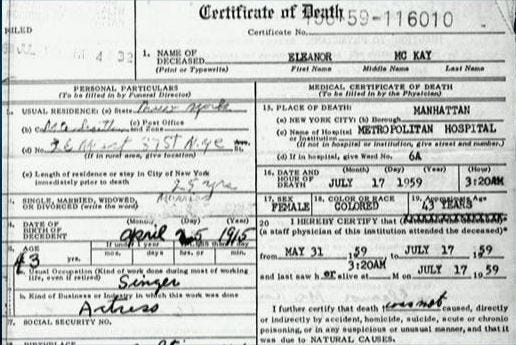

Yet even as her heart and liver stabilized, a new kidney infection was diagnosed. Some friends advised her to move to a private hospital, but Holiday was now too fragile for another relocation. Her heart was weakening too, and on July 15 a priest administered last rites. Holiday hung on until July 17, when she succumbed in the middle of night. The death certificate puts the time at 3:20 A.M. The cause of death was announced as “congestion of the lungs, accompanied by failure of the heart.”

The saddest part of this story, for me, is what happened a few hours later. Hospital workers, taking care of the body of the dead singer, found $750 taped to one of her legs. Other music stars have big bank accounts and friends to help them in a pinch. But Billie Holiday had learned the hard way to trust only herself, and the cash she had on hand.

Holiday’s life has been featured in various films and other media, which often play fast and loose with the facts. This always surprises me—because there’s no need to exaggerate here. The true story is tragic enough, and doesn’t require embroidering or Hollywood-style mythologization. Billie Holiday was the greatest jazz singer of her generation, and deserved better. She needed help, but got government surveillance and legal harassment instead. Even as she created an artistic legacy of incalculable value, she herself was let down by everyone except, perhaps, by Chiquita, Pepe, and Mister.

That’s a sad story to relate, but it ought to be told, and we can learn from it. There’s not much we can do for her at this long distance from the defining events of Billie Holiday’s final days. But a little honesty about them might be a good start.

If you want to learn more about Billie Holiday, I recommend:

Donald Clarke: Wishing on the Moon: The Life and Times of Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday with William Dufty: Lady Sings the Blues

Stuart Nicholson: Billie Holiday

John Szwed: Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth

Thanks Ted…still heartbreaking.

This reminds me of your book and how the white elite often felt compelled to claim that successful black people were damaged, or a freak of nature.