The Tragedy of Eva Cassidy

She left us 25 years ago today, at age 33—never realizing how famous and beloved she would become after her death

Today marks the 25th anniversary of Eva Cassidy’s death at age 33, and the passing of time hardly softens the blow. True, other music stars also die young, but they almost always enjoy a taste of fame and fortune before they leave us—and Cassidy had none of that. Fans celebrate her posthumous renown and record sales, but her actual life brought her mostly rejection, financial struggles, and illness.

The biggest concert of her career took place in front of a tiny audience. Her breakout music video was made on a handheld camcorder. Her most important record was self-financed. All the accolades came after her death on November 2, 1996.

Eva Cassidy would eventually sell more than ten million records, and dominate the charts with three albums and a hit single. But during most of her life, Cassidy’s music didn’t even pay the rent, and she worked for fourteen years at Behnke Nurseries in Largo, Maryland—where she watered plants, transplanted seedlings, unloaded huge bales of peat moss or truckloads of trees, and undertook a range of other greenhouse responsibilities.

Cassidy was only 5 foot 2 inches, but she did physically arduous work day after day, sometimes the only woman on a crew of men. It was dirty, tiring labor, and she kept it up as long as she could. But then the medical problems started.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

And that also differentiates Eva Cassidy from so many other music stars who died young. In those cases, even as we mourn, we recognize that their hard and fast lifestyles contributed, more often than not, to their passing. “It’s better to burn out than to fade away,” Neil Young once sang—and it’s hardly a coincidence that Kurt Cobain quoted that very line in his suicide note. But that wasn’t true of Cassidy. She died of melanoma.

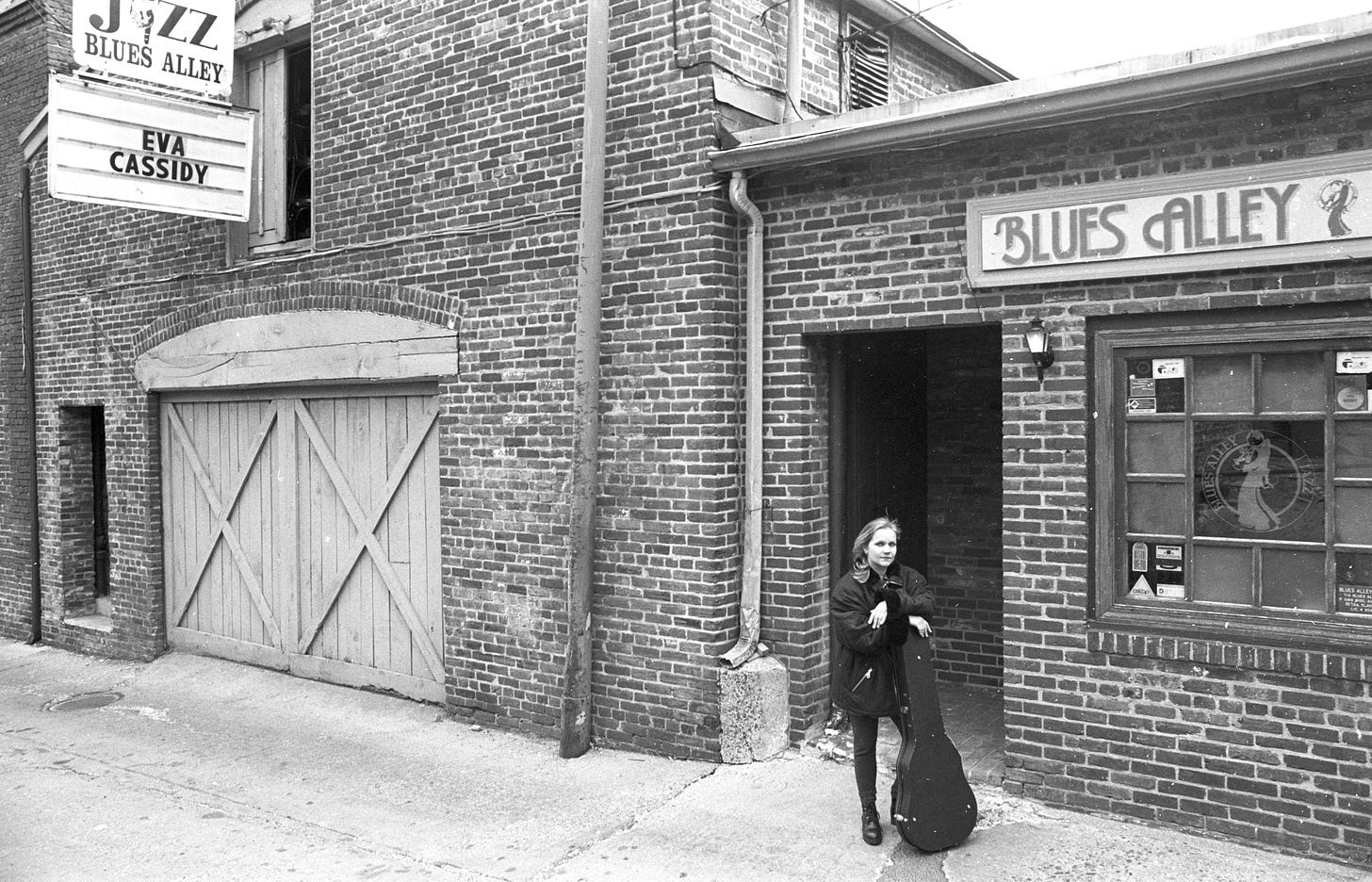

It’s a miracle that her beloved album Live at Blues Alley was even recorded. She had to cash in a small pension to cover the costs—and with all the other medical expenses, putting that money into a recording must have struck many as foolish. And even after setting up equipment to record her two-day booking at Blues Alley in Washington, D.C., technical problems forced her to discard all the tracks from the first night.

So it all came down to one evening, January 3, 1996, when Cassidy showed up for a final chance at a live album—just three days before a huge blizzard shut down the entire city. Cassidy herself was suffering from a cold, and wondered if any of the music would be worth releasing. But at this point, there was no turning back, and she took the stage, ready to sing with all the heart and soul she possessed.

You’ve heard this music, even if you don’t own the album. You may have heard it on the radio or in a playlist. Or you have heard it in movies or TV shows, where it has been licensed—everywhere from Love Actually to Maid in Manhattan. Or you have watched skaters competing with her music in the background in the Olympics. And it shows up in TV commercials, or gets sampled. Cassidy’s admirers are legion nowadays, and the forthcoming release of a 25th anniversary edition of Live at Blues Alley is likely to expand their numbers further.

Sad to say, Cassidy came very close to becoming a star in her lifetime, but it just didn’t happen. One of her admirers was Bruce Lundvall (1935-2015), a very influential person in the music business. Lundvall had run the US division of CBS Records, where he launched the careers of many superstars, and then moved to Blue Note Records, where he signed Norah Jones, whose Come Away with Me became the bestselling jazz vocal album of the 21st century, with sales of more than 25 million copies.

I spoke with Lundvall around the time of his retirement in 2010, and he said that the biggest regret of his career was not signing Eva Cassidy. A friend had brought her to his office, where she sang “Amazing Grace” unaccompanied. That’s hardly the way to win a major label record contract—solo renditions of 18th century hymns simply don’t cut it—but Lundvall was stunned by what he heard. Yet others at the label were put off by her eclecticism. Michael Cuscuna, sent by Lundvall to check out Cassidy in concert, came back with the verdict of “No direction”—almost certainly due to her willingness to sing any kind of song in any setting.

Lundvall had a final conversation with Cassidy in late 1996. He still agonized over his indecision, but by then it was too late. “It was only a short conversation,” he relates in his autobiography. “She died two or three days later.” But he knew he had made a mistake. “I should have signed her. John Hammond [the famous Columbia Records talent scout] would have done it.”

Hammond had been a mentor to Lundvall during his early years in the record industry. “John wouldn’t know a hit single if he fell over it,” Lundvall recalled, “but he told me to fight your ass off for anyone with their own voice and their own vision.” That’s how Hammond helped launch the careers of Bob Dylan, Billie Holiday, Bruce Springsteen, Count Basie, and other legends. Cassidy was exactly the kind of trend-breaking artist Hammond sought out, but in the mid-1990s the music industry was different, and Eva Cassidy was rejected for the very fact the she didn’t fit easily into any genre pigeonhole.

This was both her preference, but also a necessity given her skills and opportunities. As a freelancer, Cassidy had been forced to prove that she could sing any style. And even now it’s tempting to focus on just one of her skills, maybe her ability with slow ballads or jazz tunes. But some of her finest moments came with the least likely material.

For example, I sit in rapt admiration when I hear Cassidy sing the old folk ballad “Wayfaring Stranger”—which she turned into a soulful groove number. If you want to know how strange that decision was, listen to the way this song was originally sung. It’s one of the starkest traditional songs in the whole Anglo-American canon, and even though it has been updated, usually by country or folk singers, none of those versions even begins to prepare us for what Eva Cassidy achieves.

I call particular attention to how she raises her ambitions and intensity with each passing chorus—and 3:40 into the performance you feel she can’t possibly lift the level of her singing any higher. But she reaches deep, deep inside and delivers something you have to hear to believe.

It gives me chills to listen to this. But nobody talks about Eva Cassidy as a soul singer—and simply because there’s so much else she does, you could miss a track like this. But don’t.

By the same token, I never hear anyone describe Cassidy as a blues singer. But listen to what she does with “Stormy Monday,” and you will realize she could have built a whole career on raw, gritty songs of this sort.

Her ballad singing is so emotionally charged that her cover versions raise comparisons with the original hit records. Her renditions of Paul Simon’s songs even got his attention, and he has publicly praised her version of “Kathy’s Song.” “Eva Cassidy is one of the best Paul Simon interpreters,” music critic Geoffrey Himes has commented, and that claim is further backed up by her versions of “American Tune” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” And though I’m an admirer of Sting’s work, his song “Fields of Gold” made no impression on me until I heard Cassiday’s intimate reworking, which is heartbreaking in a way the more declamatory original simply isn’t.

But her most unlikely success was achieved with a song that was more than sixty years old, and performed so often that few would expect it had any new secrets to share. But at Blues Alley that night, Cassidy decided to sing “Over the Rainbow” from the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. Once again, this is the last thing you would do if you were aiming for a hit pop record in the digital age, but Cassidy picked songs because she loved them, not because they matched the items on an A&R executive’s check list.

Like me, Cassidy had heard this song every year as a child, when The Wizard of Oz was broadcast as an annual ritual on network television. She had performed it previously at a high-profile Washington DC music award show and left the audience stunned. “When she came out, I was just worried, you know, the audience was milling around and talking,” the show’s promoter Mike Schreibman later recalled. Eva’s father said that he heard someone remark: “Don’t tell me that little girl is going to try ‘Over the Rainbow’ on THIS crowd.” But they had never heard it sung like this before. “When she started to sing, they just… stopped,” Schreibman continues. “So many times I’ve heard since then, that was the first time they heard her, and how great she was. Ron Holloway said that he was on the way out the door but when he heard Eva he came back in.”

So at Blues Alley, with the recording equipment that her cashed-out pension had hired capturing this one night of music, she decided to sing it again, accompanying herself on guitar. And this performance, also preserved on film, did more than anything to catapult her to fame.

It didn’t happen until five years after Cassidy’s death. The track got some airplay. The video found its way on to a high-profile BBC show, Top of the Pops 2—and then, against all odds, became the most requested video in the show’s history. We’re talking about an amateur camcorder film, one that the network had been reluctant to broadcast even the first time.

Her album rose to number one on the UK charts. And in Ireland too. It started selling in the US, and then selling more, and soon going platinum. Cassidy was now enjoying hit records in Germany, Australia, Sweden, Switzerland, and other countries. It looked like the biggest new singer of the 21st century was someone who had died before the new millennium had even begun.

How can you watch this poignant video, and not think of that place beyond the rainbow as the fame she never tasted, the successes she never knew about because they happened too late, or the years and decades robbed from her by illness—and just a month after the Blues Alley gig, doctors told her that the cancer was terminal.

But in a way she did achieve that somewhere over the rainbow—that place where, as the lyrics promise, “the dreams you dare to dream come true.” Her songs have given her the kind of immortality that Shakespeare and Villon and the poets have written about, and which only art confers. We benefit from it, even if she didn’t. And still do after twenty-five years. I just wish she was here to see how it all turned out.

Here’s a link to my Qobuz playlist of music by Eva Cassidy.

DC Go Go music is not a widely known genre ... a little R&B, funk, and music that just doesn't stop ... because it is dance hall music first and foremost. And the person who made it most famous, even if he didn't invent it was Chuck Brown ... who was probably the most important person in Eva Cassidy's early career. It seems really strange ... but maybe it's just because they understood--like Duke said--that there's only two kinds of music--good and bad--and both Chuck and Eva made the latter kind and appreciated each other's efforts. See this: https://www.evacassidyfanclub.nl/blog/2012/05/obituary-chuck-brown-1936-2012/

Thanks Ted for reminding me of Eva Cassidy. I remember the posthumous buzz about her around the turn of the century. I sampled some of her material back then but at the time "I didn't get it". Now, having listened to the 25th anniversary of Live at Blues Alley multiple times thanks to your story, I am gobsmacked by her talent. It's not just her voice; she has a unique way of phrasing and rythmn and "space between the notes" that puts her stamp on old chestnuts such as "Cheek to Cheek" to make the song her own. I normally am not drawn to a "pure" voice like Eva's, preferring rather some "character" such as a Townes Van Zandt , Howe Gelb, or Sue Foley. But Eva is different. I think her sincerity and authenticity shines through. And her voice is magnificent! There is never a "reach" for a note with her; it's just flawless. She could have been the top at many styles of singing; jazz chanteuse, blues belter, or folk singer. And her having not been signed to a label because she didn't have a direction or was too "scattered" is a tragedy itself; a consequence of the sub-genre categorization of music. But what hope I take from her story is that there have got to be other "Evas" out there waiting to be "discovered". I have heard many artists on bandcamp and Spotify just by random chance that I prefer to the so-called "mainstream" artists of today. Let's hope the next "Eva" gets to enjoy her success during her lifetime.