The Rise and Fall of The Village Voice

A new book reminds us what we lost when the counterculture disappeared

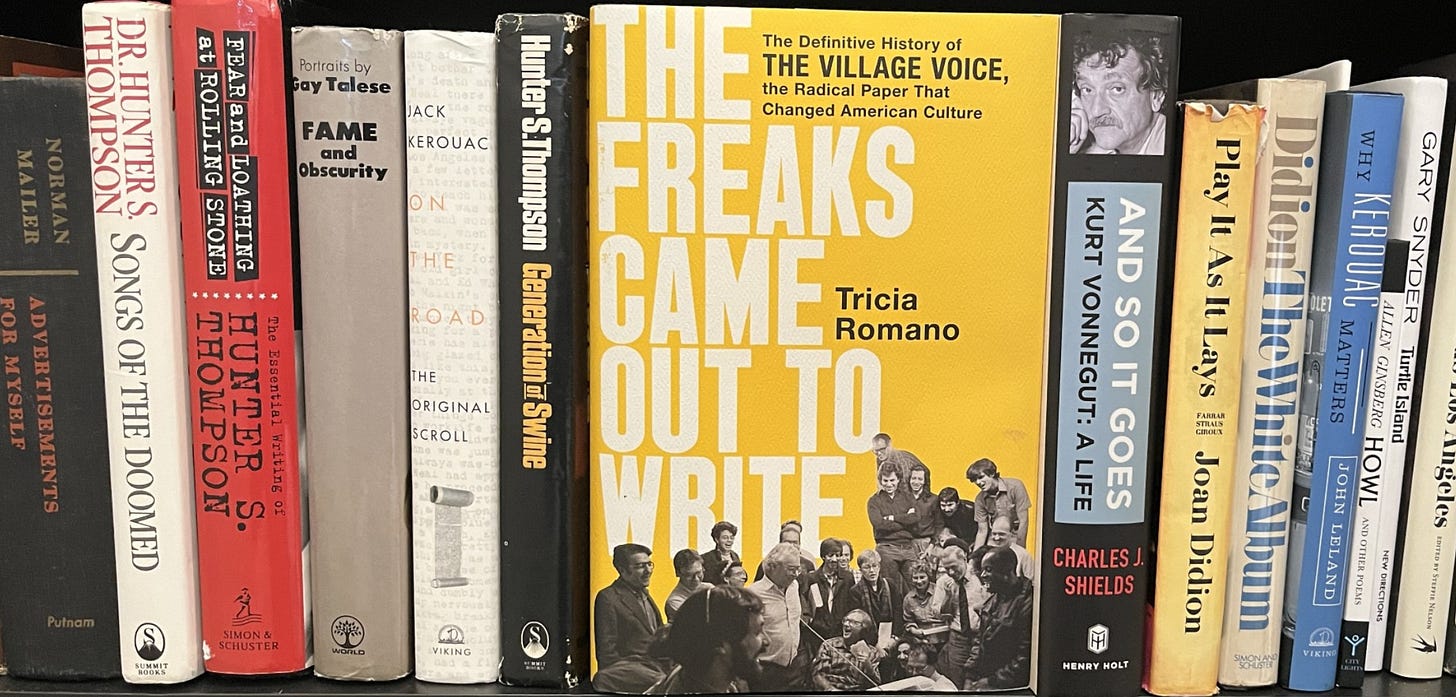

At the start of her oral history of The Village Voice, author Tricia Romano provides a “cast of characters.” It goes on for 15 pages, and includes 216 people—each with some connection to the alternative newspaper.

Many people nowadays have never lived in a society with such a vibrant counterculture. In a time when official sources all seem part of a predictable Disney-fied monoculture, just reading this list of names and mini-bios can be a revelation.

Many of these individuals are now revered as historic figures who changed society. They had power and prestige. It’s easy to forget that most of them operated as outsiders.

That’s how they wanted it.

If you want to support my work, click here to upgrade to a premium subscription (for $6 per month).

These renegades at The Village Voice knew that working outside the system—and typically against the system—was their superpower. They could criticize ruling institutions. They could speak harsh truths. They could go against the grain.

One thing’s is certain: They didn’t align their interests with globalist corporate CEOs, billionaire technocrats, the surveillance state, and establishment bureaucracies. They would have laughed at journalists who did that—believing, rightly, that honest media requires distance, or even an adversarial stance, vis-à-vis entrenched powers.

Because that’s what a counterculture does. That’s what it’s expected to do.

“I’m sure that every major person at the Voice had an FBI file.”

Romano captures the peculiar vibe in the title of her book The Freaks Came Out to Write. She makes clear that The Village Voice wasn’t The New York Times and it definitely wasn’t The New Yorker.

Nobody ever stepped into its madcap offices and said “Ah, the Gray Lady.” No reader ever picked up a copy and expected to see Eustace Tilley on the cover.

And The Voice was heard. Even establishment insiders knew they needed to listen to these ‘Freaks’. Sometimes they feared The Voice, sometimes they secretly agreed with it, but they always treated it as a force deserving respect.

Until recently that’s how it worked. The tension between insiders and outsiders was a source of creative energy in society. The upstarts provided alternative views and new ideas. They kept everybody accountable.

I’m pointing this out because this no longer happens. This is the world we’ve lost.

Today we still have alternative views and alternative platforms. Substack—the platform where I publish The Honest Broker—is one of them. And there are many of others. But the mainstream typically views these alternative voices with indifference, neglect, or outright hostility—often working to delegitimize them.

Every article I’ve read about Substack in the mainstream press has been a hit piece. And other outsider platforms don’t even get attacked—some alt media stars have an audience in the millions (or tens of millions), but their names are never mentioned by the monoculture. They’re not even outsiders, more like exiles.

I’m not exaggerating when I say there’s a war going on between the macroculture and these alternative platforms.

So I read Romano’s history of The Village Voice with a little nostalgia and a lot of envy. We need something like The Voice today. The system ought to support critics of the system—if only to ensure its own heath and survival.

These oral histories show how things once worked. Here’s a little taste:

“I’m sure that every major person at the Voice had an FBI file.”

Nick Hentoff

“The person who covered hippies was Don McNeill. He was a homeless guy. He had a bed on the top floor of the office. He knew the scene; he lived what he wrote about.”

Richard Goldstein.

“The whole idea of countercultural journalism was invented by The Voice, really….It was the investigation of everything you wouldn’t find on the regular grid, and it would clue you in to where culture was going if it were not corporately produced and directed.”

Laurie Stone

“We got a lot writers just walking in the door….They simply walked in, sat down, and started talking….[Future Pulitzer winner] Jules Feiffer walked in one day with a pile of cartoons under his arm, and he said, ‘I’ve been to every publisher in New York, and nobody wants what I have. If you want them you can have them for nothing.’”

Ed Fancher

“[Robert] Christgau was hated by bands because he was so honest, and he was so brutal. There’s a single out there, I forgot who did it, called ‘I Killed Christgau.’”

Frank Ruscitti

‘The first person to ever write about Spike Lee in the paper was me. Spike cold-called me at The Voice one day….It was his school project. It was genius. I loved it….Chris Blackwell read what I wrote and got in touch with him and ended up funding She’s Gotta Have It.”

Carol Cooper

“I got a call from Robert Morgenthau….And he said, ‘I’ve been reading these articles about [prosecuted and censored comedian] Lenny Bruce….I never thought about running for district attorney but now I’m interested’….That’s why Robert Morgenthau became the longest-serving district attorney in New York.”

Nat Hentoff

When did The Voice lose its way? As a music fan, I might point to 2006 when Robert Christgau and eight other members of the arts staff got fired. Or maybe the forced departure of Nat Hentoff in 2008 was the final straw. (Full disclosure: I hired Hentoff to write for me at Jazz.com a few days later.)

But, in all fairness, The Village Voice could have survived these changes, just as it had survived the death of Lester Bangs or Stanley Crouch’s exit (after a violent altercation on the premises). They just needed to find the next great writer to fill the empty big shoes.

They couldn’t do it. The world had changed. Borrowing the melody of a Brazos River cane-cutting song, I’m forced to sing.

Taint no more print readers in the Village demographic.

The Internet came and pillaged all the traffic.

The Village Voice lasted a few years longer as a print newspaper, but that stopped in 2017. Today the periodical exists online, and occasionally in print, but don’t be fooled. The name may be the same but the magic is long gone.

But, Lordy, those outsiders are everywhere now. They are submerged in alt platforms—and will never win Pulitzer Prizes, MacArthur Fellowships, or other perks of insiderdom.

But the audience is paying attention. They don’t need to see validation from elites—that would actually make them suspicious. Much like readers of The Village Voice in the 1960s, they trust the outsider more than the insider.

The only people who haven’t figured this out yet are the entrenched insiders. They think these pesky rivals working out of their apartments will just go away.

It’s not going to happen. The opposite is taking place.

Sure, the quality is mixed in the alt media. But if you pick wisely, you reap the benefits—that’s the single best way of replicating The Village Voice in a world where alt newspapers have disappeared. In fact, there’s a whole flourishing media ecosystem out there on podcasts and video channels and Substacks, etc.

The only difference is that the monoculture doesn’t want you to know that these alternatives even exist. Maybe they can’t hide them—that’s impossible because some individual alt media stars now have more subscribers than the Gray Lady and Eustace Tilley combined—but institutional insiders can, perhaps, slow these upstarts down with hit pieces and smug dismissals.

That’s why the alt voices aren’t even called a counter-culture. Just whispering the word would give them too much legitimacy.

But in a media ecosystem where entrenched interests do the legitimizing, it might just be wiser to operate without it.

“[Robert] Christgau was hated by bands because he was so honest, and he was so brutal. There’s a single out there, I forgot who did it, called ‘I Killed Christgau.’”

Frank Ruscitti

Oh, it’s worse than that—it’s called “I killed Robert Christgau with my big fucking dick”, by Sonic Youth

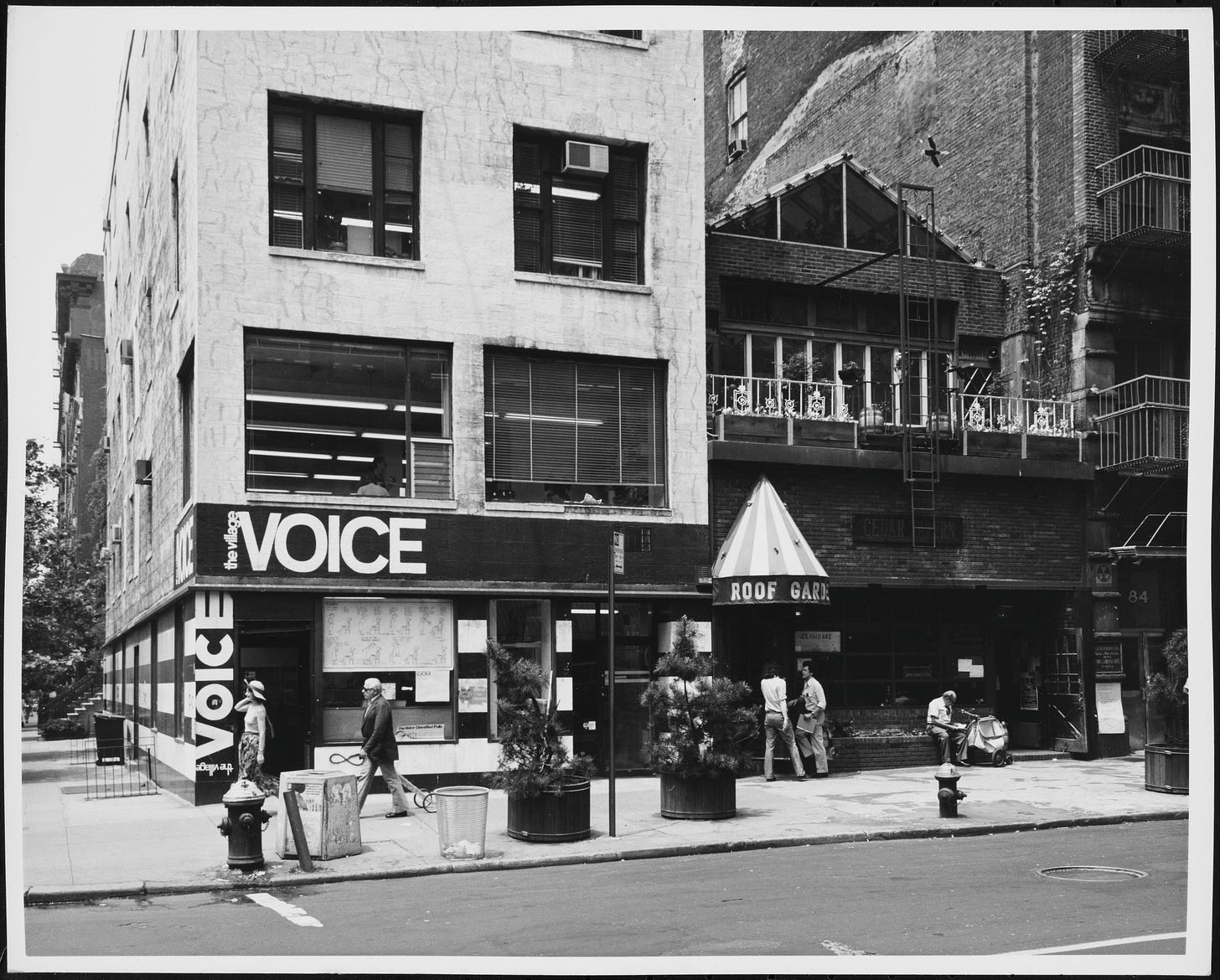

As an art student, I lived in the village in the late 70's, and The Cedar Tavern, (to the right of the Voice offices in the posted photo), was a frequent watering hole for many of us. The Tavern and The Voice were part of the neighborhood, not outposts, but destinations for the like-minded, for artists and writers to feel a sense of community. Today, the idea of community gets batted around the internet as if it is a tangible thing in a virtual world, it's simply not the same. As much as I value being a subscriber to The Honest Broker and feeling a sense of kinship, I miss the connectedness that came from sitting with a future "Ted Gioia" in what I recall as a welcoming and supportive environment for sharing all the wonder and frustration of experiencing the life from a different perspective. The Village Voice was more than a newspaper, in a way, it was the neighborhood. Thank you Mr Gioia for your thoughtful work. - Cheers