The Remarkable Diaries of Composer Ned Rorem (Who Celebrates His 99th Birthday Today)

I adore the music of Ned Rorem, but he is also the greatest diarist of the second half of the 20th century

Composer Ned Rorem shook up New York in 1966—and it had little to do with his music.

Make no mistake, Rorem deserves respect as one of the finest American composers of his generation. He brought home a Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his Air Music: Ten Etudes for Orchestra, and fittingly so. His entire body of work, especially the hundreds of art songs composed over more than sixty years, is rich and rewarding. And he’s very underrated as a composer for piano. But in his youth, Ned Rorem embarked on another pursuit, and it would find an even larger audience than any of these musical works.

Back in 1936, Rorem started keeping a diary—he was just twelve years old. He gave it up after a few months, but in 1945, Rorem began again. And now he maintained the practice with vigilance, zeal, and (most importantly) genuine talent as a diarist, never flagging as the years and decades passed by.

Only a tiny part of this journal was published in 1966—drawing on entries Rorem wrote in the early 1950s while residing in France and North Africa. But when it showed up in bookstores as The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem, the whole world took notice. Well, at least the tastemakers and elites of New York and other enclaves of high culture, and that’s close enough for those seeking fame and fortune in creative pursuits.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Cultural elites had good reason to pay attention. They might find their own name in Rorem’s indiscreet scribblings. Here readers got up close and personal with John Cage, Salvador Dali, James Baldwin, Man Ray, Darius Milhaud, Paul Bowles, François Poulenc, Alice B. Toklas, and many, many others. You could read this book in various ways—for scandal, for enjoyment, or simply for the vicarious thrill of experiencing Rorem’s wanton ways at secondhand. But read it you must, at least if you were part of that milieu—and if you didn’t, you would still hear what Rorem had to say from those who did.

One reviewer passed judgment on the diaries in just five perfectly chosen words: “worldly, intelligent, licentious, highly indiscreet.” In his introduction to The Paris Diary, Robert Phelps reaches even higher, drawing on comparisons with everyone from Whitman to Poe, before describing the author as a “social climber” and “earnest narcissist”—as wells as “an intellectual, a hero-worshiper, an excessive drinker of alcohol, and a lover,” whose daily jottings were “better written, more aptly observed, less fearfully self-guarding” than other first-person chronicles of its time.

The published diary takes off with vigor right out of the starting gate, but begins with a lie—or perhaps a warning about the unreliability of all narrators. At the top of page one of The Paris Diary, Rorem (in 1951) writes:

A stranger asks, ‘Are you Ned Rorem?’ I answer, ‘No,’ adding, however, that I’ve heard of and would like to meet him.

And then we are off to the races. Sex and booze already make their appearance on this opening page. Picasso shows up on page two, as well as Valentine Hugo, who asks Rorem to play piano while she recreates the dance steps she did for Stravinsky at the premier of The Rite of Spring in 1913. On page three the diarist admits to his doubts as a composer, and lists the musicians he steals from. On page four, Rorem meets Jean Cocteau and has his portrait painted by the Vicomtesse de Noailles. Rorem starts a love affair with the Vicomtesse before we get to page five.

Has any novel ever moved this fast? We tend to view diaries as slow-moving accounts, inferior to more stylized narratives, not much different than those brain-numbing Instagram accounts that post photos of an influencer’s most recent meal. But Rorem moves too fast to linger over dinner, let alone take snapshots of the dishes.

The name-dropping alone is off the charts. But Rorem is quick to downplay his social achievements—honestly, he insists, there are only around 75 people who matter in Parisian snobbish circles. After the first party you know them all. But he also makes clear that musicians operate at the highest level of this hierarchy, and that he makes full use of the privileges his métier assigns.

The gossipy parts got the most notice. But Rorem’s diaries were more than just a flurry of hobnobbing and knob-hopping. The reader is treated to choice aphorisms amid the debauchery:

“The best music must be nasty as well as beautiful.”

“Wagner, too, I love, if I don’t have to listen to him.”

“I am physically attracted to everyone here except one person. Who? Myself.”

“The end of love is like the Boléro played backwards.”

“The artist answers questions that have not yet been asked.”

“Americans say what they think, the French think what they say.”

“Like all great comics, Chaplin lacks a sense of humor.”

“I’ve already said everything I have to say. Including that sentence.”

A few months after the release of The Paris Diary, Rorem published The New York Diary, drawing on journal entries from 1955 through 1961. His time in France had made him more observant of shifts in American life, even tiny neologisms. (A jotted note: “The new slang: goof, to miss, make a mistake; Flip: swoon with enthusiasm.”) But he’s also on the lookout for bigger innovations. He makes an inquiry at a bar about S&M parties. “Don’t kid yourself,” he’s told, “they just hit each other with a bunch of wet Kleenex.” He discovers the Turkish baths of Manhattan, which are perfect both for curing a hangover, and addressing the one-track carnal awareness of the afternoon after.”

But now he’s at El Morocco at midnight with Marlene Dietrich, Truman Capote, and Harold Arlen. When Dietrich goes to the “powder room,” Arlen offers some coins to tip the attendant, but the grand actress scorns them, demanding bills. “After all, coming from me,” she explains, “noblesse oblige.” A few days later, Rorem crashes a therapy group led by Paul Goodman, and tries to break the ice with cocktail party chatter, before Goodman stops him short: “Ned, the artifice of your social style, your charm will be your downfall.” The rest of the session is devoted to savage attacks on Rorem from all participants, who later boasts in his diary: “Charm or not, I had been the center of attention.”

In a flash, Ned swears off drink and attends A.A. meetings. But a few pages later he’s singing the praises of mescaline. Yet new anxieties emerge—Rorem worries that the trendiness of pot will make his old school alcoholism and psychoanalysis seem démodé. What point is there in getting drunk, after all, if you can’t be a fashionable drunk?

The reader, however, has different anxieties. Most notably: How long can Ned Rorem keep this up? Even after reading just a few pages, you would never underwrite a life insurance policy for this gadabout, let alone anticipate him living to the ripe age of 99.

Ah, but we aren’t insurance underwriters, so we can’t help reading on. And what can be more exciting than following Ned Rorem from party to party, incident to incident? At one gathering, he compares seduction notes with Jack Kerouac. At another, he mocks Edward Albee with the assertion that literary theater died 150 years ago—yet wily Albee dedicates a play (about Bessie Smith) to him. Rorem gripes when a jazz piece by Bill Russo is played on the same program as his serious music, ridiculing trumpeter Maynard Ferguson, whose solos “like Truman Capote’s opinions, sometimes reached pitches only dogs can hear.”

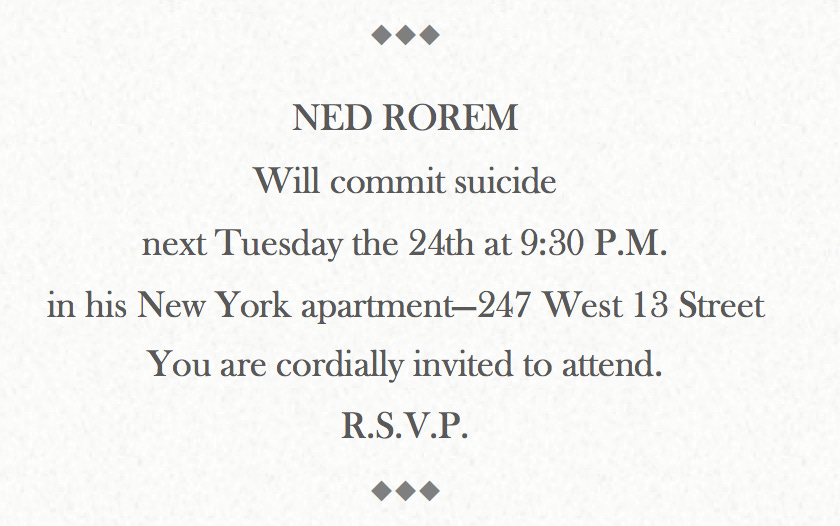

Along the way he notes the death of an endless litany of celebrities in his diary entries—Jean Sibelius, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Tyrone Power, Christian Dior, Albert Camus, Ezra Pound, etc. etc.—and even composes a mock invitation to his own demise:

Can anyone really live like this? If you believe the diaries, at least one person managed to pull it off.

Even so, few individuals have risen from an upbringing less suitable for pursuing a career as a bon vivant. Ned Rorem was born in Richmond, Indiana in 1923, and raised in a Quaker household. At one point in his memoir Knowing When to Stop, Rorem lists all the exciting cultural developments of 1920 in Paris and New York before mentioning that, at the same moment, in Yankton, South Dakota, “my mother met my father at a picnic in the early spring.” The couple were married in Sioux Falls in 1922, the year of Ulysses, “The Waste Land,” and the death of Proust. A short while later, Ned was born—“slipped out like an eel,” according to his mother, the composer relates with some pride.

A move to Chicago in 1924 gave this young Quaker boy access to a more worldly education, and he soon revealed his musical talent. He aspired to greatness as a composer, but young Ned Rorem had other goals too. While a student at Northwestern he was already striving to impress famous people. When Thomas Mann gave a lecture on campus, Rorem later admitted, “I disguised myself as Tadzio and sat in the front row of Scott Hall imagining to divert him—without avail.”

Rorem’s good looks are an ongoing part of the story of his life. The diaries both highlight Rorem’s physical appeal, and downplay it. When a friend confronts him, accusing him of using his looks to advance his career, Rorem vehemently denies it, asserting that most of his opportunities come from people who hadn’t seen him in the flesh. Yet he also makes sure to put 16 pages of photos at the start of The Paris Diary, insisting that readers take full measure of his boyish charms before they encounter his prose. He might be a mere compositeur, but Rorem was no fool, and knew precisely what he had to do to make a memorable first impression.

Rorem’s indefatigable diary-writing continued long after he had made these first impressions—whether on readers, concert audiences, or attendees at some fashionable party. Many might have been tempted to dismiss him as an attention-seeker, but he also had to be taken with utmost seriousness as a composer, a pursuit in which he was just as prolific as he was in making journal entries.

But the diaries probably made it harder for Ned Rorem in his chosen vocation. In 1956, a journalist smugly declared that Rorem was the worst American composer—and in typical fashion, the victim of this barb bragged about it in his diary as “unique true glory.” But Rorem’s worst sin, as a composer at least, was operating outside the ascendant musical trends of his era. There was considerable irony in that, given his image as someone so embedded in the most fashionable currents of modern life. Yet as serialism and compositional strategies started to lose their lockhold as dominant paradigms among serious (note italics = irony) composers, Rorem no longer seemed quite so out-of-touch. His inherent musicality—never in doubt for those who had ears—demanded more respect. You might even wonder why more people hadn’t been listening all along?

Maybe because they were reading Rorem, not hearing him?

And the books continued to appear. The Later Diaries encompassed more than a decade, from 1961 to 1972, but the book was poorly named—as it turned out, Rorem wasn’t even at the midpoint of his lifelong diary-keeping project. The Nantucket Diary, published in 1987, covers the period from 1973 to 1985, and here the tone starts to change markedly. Instead of starting the book with a love affair, Rorem visits a proctologist on page one, but also finds his last name as a clue in the New York Times crossword (the answer is N-E-D). Life has clearly changed for Ned Rorem, no longer a boyish upstart, and the writing is a tad less scandalous.

But these later diary entries are even more interesting for those seeking insights on music. Rorem is more confident—and acerbic—than ever before when passing judgment on the music scene as it passes by in a flurry of concerts, private conversations, and social encounters. You might even conclude that Ned Rorem is now settling more scores than he composes.

This is my favorite period of the Rorem diaries. The musical verdicts come in waves, page after page, never stopping. And even if he makes outrageous feints and gestures—for example, comparing Stockhausen to Jesus Christ Superstar (the rock opera, admittedly, not the person, but still something of a stretch)—the entries are all the more compelling for his unapologetic invective. He denounces Elliott Carter’s Night Fantasies as chaos and writhes when his companion treats it as if it’s as lovely as a Chopin nocturne. He refuses to attend an ASCAP event unless the program makes clear that Marvin Hamlisch did NOT win a Pulitzer Prize in music for A Chorus Line.

And it never stops. Charles Ives is branded as “madly uneven” while Maurice Ravel is praised as “sanely consistent”—or is that praise? Rorem gripes that Vladimir Horowitz receives too much adulation, because “who is Horowitz compared with, say, Stravinsky.” (The notion that composers deserve more acclaim than performers is a recurring theme here.) Shifting gears, Rorem complains that there’s nothing wrong with Diana Ross, and “that’s what’s wrong.” But he adores Billie Holiday, who he praises again just as he did in other diary entries decades ago.

Do I agree with all of his assessments? Not at all—although Rorem has a pretty good batting average. Do I keep reading? Absolutely?

I should add that there’s still plenty of sex and partying here. Rorem tells about his fling with novelist John Cheever, and mulls over the fact that his diary revelations have somehow turned him, even if only briefly, into “America’s official queer”—but Rorem clarifies that he merely managed to hold the title in the goyim division. Who could compete with Allen Ginsberg, after all? Even so, he cringes at the essentializing label, announcing: “I am not a homosexual. I am a composer. I am not a composer. I am Ned Rorem.” The artist, he insists, “must proceed from the broad to the final particular, or perish.”

The Nantucket Diary alone could have established his preeminence as a diarist, but Rorem was far from finished with his journaling. In 2000, he published a new batch of entries under the beguiling title of Lies—reminding us of the first entry in his old Paris diary, when he denied being Ned Rorem— and it covers the period from 1986, when Rorem turned 63, to 1999, when he celebrated his 76th birthday.

The journal entries are now less ebullient, more colored by mourning and melancholy—but Rorem still has much to say long after he has abandoned the stance of the fair-haired boy. His deep observational powers, accompanied by wit and insight, continue to draw the reader on page after page, even as Rorem deals with the ravages of aging, grim political news, and the toll the AIDS crisis takes on his friends. And after that, Rorem still kept up the now six-decade long habit with Facing the Night, covering 1999 to 2005.

In that book, Rorem promised that, if he ever published another volume of diaries, he would call it Truth. But if it’s written it hasn’t been published—then again, maybe you need to wait for posthumous immunity before genuine truth-telling can start. In any event, Rorem no longer shares his diary entries, and may have stopped writing them too, as far as I know. But he anticipated that in his first book, when he proclaimed in honor of youth: “We know nothing old we did not know as children.” To his credit, Rorem was a very deep young man, yet that only set the stage for becoming an even deeper old man.

The end result is a literary achievement unmatched by any other composer. In aggregate, the Rorem diaries are the most remarkable firsthand documentation we have of a musical life—surpassing those of Charles Burney, Sergei Prokofiev, Benjamin Britten, or whomever else you care to cite. Not even Mozart’s voluminous letters can match the scope and depth of Rorem’s six decades of journaling. He operates on a larger sphere, up there with Pepys and Boswell and others at the pinnacle of the diary as a literary genre.

Frankly, I’m most amused by the frequent anxieties, expressed in these pages, over how long people will remember Ned Rorem’s music. Those compositions really shouldn’t be forgotten, although it’s hard to predict the future of musical reputations. Yet what amuses me most is that Rorem has almost certainly ensured the survival of his music through the success of his momentous memoir-making. These journals alone will be enough to keep his music playing. After all, Ned Rorem long ago established himself as far more than a mere composer—he’s part of the fabric of modern cultural history.

Even so, the best reason to read Rorem’s diaries and listen to his music can be summed up in a simpler proposition: You will enjoy the experience, and want to come back for more. And I suspect that’s exactly how Ned Rorem—or any musician or writer, for that matter—wants to be remembered.

So if you’re like me, sooner or later you will go back to that first Paris diary, and turning to page one, nod your head in agreement while you read:

A stranger asks, ‘Are you Ned Rorem?’ I answer, ‘No,’ adding, however, that I’ve heard of and would like to meet him.

Thanks for this. I had the honor of studying with Ned for three weeks in 1984 at The Atlantic Center for the Arts in Florida. He was 60 and looked 40. In those weeks I learned more about what it means to be a composer than I had learned studying for years with teachers at a university School of Music. Every day, Ned would assign his pool of students -- I think there were 6 of us, including Daron Hagen, the only one who would go on to make a name for himself -- a poem to set for voice and piano by the next day. The texts ranged from Tennyson to Wallace Stevens. Once the assignments were turned in, Ned would throw each song on the piano rack and sing and play it at sight. Then he would point out each song's strengths and weaknesses. That simple, that effective. He was still journaling in those days and I made mention in his Nantucket Diary, sans scandal. Thank you, Ned.

“I’ve already said everything I have to say. Including that sentence.”

On a par with John Cage: "I have nothing to say, and I am saying it." Who was first? Or, who's on first?

" . . . Ned Rorem is now settling more scores than he composes." Thanks, Mr. Gioia for that little gem!

“I am not a homosexual. I am a composer. I am not a composer. I am Ned Rorem.” Love this, and one doesn't have to be "woke," which is largely a silly construct of the far right, to wish for a time in which a woman is simply a "composer/artist/sculptor/author/etc." and NOT a "female/gay/trans/etc." such.

Not important what I am, but I am Tom Rhea.