The Plan to Turn Thelonious Monk into a Jazz-Rock Fusion Star

Even as the prickly pianist was retreating from the jazz scene, his label schemed on a collaboration with a superstar rock band

In 1962, Columbia Records signed Thelonious Monk to his first major label contract. He had previously made great albums, but always for indie jazz labels—first Blue Note (1947-1952), then Prestige (1952-1954), and finally Riverside (1955-1961). Yet those outfits didn’t have the marketing clout of a major label like Columbia.

He may be a legend today, but Monk was hardly making the kind of money he deserved back in the 1950s. For most of the decade, he was hardly making any money at all.

Just consider the amazing fact that Orrin Keepnews of Riverside bought out Monk’s contract with Prestige for a total payment of $108.27.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Monk’s prospects would soon improve, but even those Riverside albums—now defining classics of modern jazz piano—got a mixed response at the time. Nat Hentoff was wise enough to give Monk’s Brilliant Corners album a five-star review in Down Beat, but other critics writing in that same magazine often served up vague, dismissive comments on these now beloved recordings. And the New York Times critic who reviewed Monk’s Town Hall concert, released on record by Riverside in 1959, went so far as to complain that the pianist played “with a graceless force” and his music “was blighted by some pixyish conceptions.”

I’m not exactly sure what that means—but I don’t think it was a compliment.

It’s rough getting dissed in the NY Times, but Monk had grown familiar with smug reviews of this sort. But he had even more powerful opponents at the time than the Gray Lady—New York City police took away his cabaret card in 1951, limiting his ability to perform in local nightclubs for most of the decade.

And as if that wasn’t enough, the US Postal Service issued a restraining order to stop Riverside from distributing imaginary Monk postage stamps as marketing material for The Unique Thelonious Monk, released in 1956.

Those Riverside albums from the late 1950s are my favorite Monk records, but Columbia clearly was a more powerful ally for the pianist. They proved this definitively in February 1964, when Thelonious Monk appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Monk deserved the honor, but it would never have happened if he was still recording for small indie labels.

Even so, working for Columbia came at a cost. The execs at that label loved jazz, but they especially loved jazz that found a large crossover audience. And with each passing year, Columbia became less patient with musicians who didn’t jump on trends and chase sales.

This process culminated in what I’ve called “the worst day in jazz history.” Others have called it the “Great Columbia Jazz Purge.” This was the dark moment when the most powerful label in American music, and a longstanding supporter of jazz, dumped Ornette Coleman, Bill Evans, Keith Jarrett, and Charles Mingus from their roster.

According to legend, this all happened in a single day—but that may be more fanciful than accurate. Yet the larger truth was undeniable: Columbia was ready to abandon even legendary artists who are still revered 50 years later, if they didn’t update their approach and generate immediate rock-climbing sales.

Even from a purely financial perspective, this was a huge mistake. Keith Jarrett would sell millions of records over the next decade, and release the biggest selling solo piano album up to that point in history—but had to do it with the German-based ECM label, because Columbia didn’t grasp his potential. Ornette Coleman would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize in music, something none of the label’s pop stars could even dream of. Mingus and Evans, for their part, are still huge moneymakers in jazz today—even though they both died more than 40 years ago.

Each of those artists will still be a big deal in a hundred years, but Columbia was instead obsessed with how their new albums would sell in the next hundred days. Not even that, when you think about it—because shareholders demand to see income statements every three months. So more like 90 days.

Nobody with the slightest jazz connection at Columbia was immune to the new commercial push. Clive Davis at Columbia pressured Tony Bennett to record rock songs—by his own account the singer got physically ill in reaction to music they wanted him to sing. He, too, was soon gone from the label. Miles Davis, in contrast, embraced the new rock sound with enthusiasm, and generated huge sales with his Bitches Brew album. But I have no doubt that even that jazz legend would have been forced out if he hadn’t bought into the new paradigm.

Columbia’s priorities were clear—they still wanted to play a role in jazz, but only when it sounded like rock.

And now we arrive at the strange case of Thelonious Monk. No musician on the Columbia roster was less suited for a rock image remake than Monk. Yet the folks in suits at head office desperately wanted that to happen.

You can already detect the rebranding campaign in the album cover to Underground Monk, released by Columbia in 1968. If you saw that cover today, you would assume it resulted from careful photoshopping and image manipulation. But the marketing team actually staged this extraordinary setting—depicting the pianist as a resistance fighter, playing the piano with a machine gun at his side, and grenades and other weapons nearby, all situated in an underground bunker.

The setting could hardly have been further from reality. Monk actually showed up for the photo shoot in one of (his wealthy patron) Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter’s limousines, a Bentley or Rolls Royce—with the baroness acting as chauffeur. He sat down at the battered piano brought to the studio (not really underground, but set up in a townhouse off Third Avenue). He didn’t say a word to anyone—except for greeting the cow with a friendly moo—and played piano during the photo shoot, leaving in the limo an hour or so later.

But image is everything. This was the same year that protesters set up barricades in the streets in Paris, and battled police at the Democratic Convention in Chicago. A gun-toting Monk operating from a hidden command post was precisely the perfect cool pose for the time.

If you had any doubts, here’s the opening of the press release that accompanied the album’s launch:

“Now, in 1968, with rock music and psychedelia capturing the imagination of young America, Thelonious Monk has once again become an underground hero, this time as an oracle of the new underground. . . .”

I’ll admit that I love this cover—it’s one of my all time favorites—but it really has nothing to do with the music on the album. The tracks on Underground Monk featured the pianist’s working band performing a mix of mostly Monk originals, some of them the same tunes he had been playing for years. The new material included a waltz (a rarity for Monk), and a birthday song for the his daughter.

Fine stuff, all round. But none of it required a cow or bunker, let alone a machine gun.

What the cover did accurately represent was the hopes and dreams of Columbia execs, who desperately wanted a new revolution from Monk, something different from his old songs. They took some comfort in the fact that he was already showing up at the right places—when Underground Monk appeared, the pianist traveled to California to play at Berkeley, followed by a stint at the Carousel Ballroom, where the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane performed.

Despite all this, Underground Monk sold poorly and did little to build Monk’s following with teens and rock fans. A follow-up album, Monk’s Blues, added more contemporary big band charts, but this still failed to produce sufficient sales to impress the Columbia bosses, who would soon start purging the label of its jazz stars.

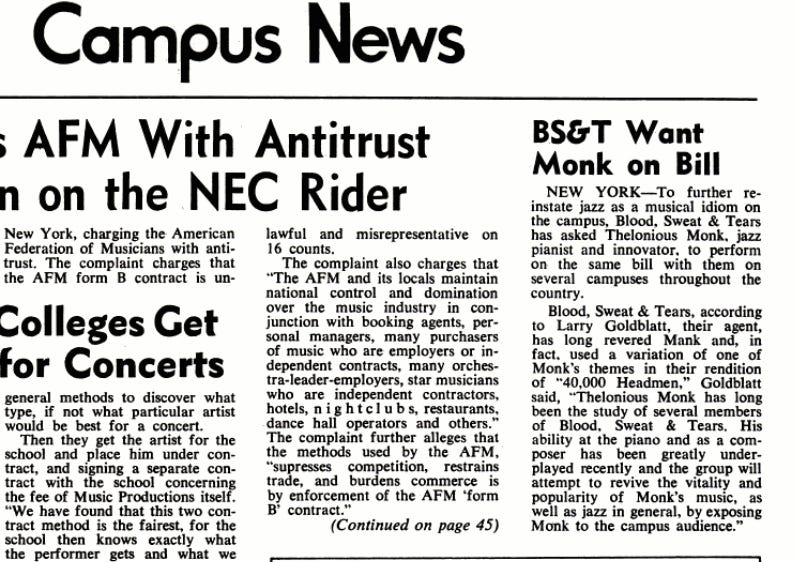

This is where the band Blood, Sweat & Tears came into play. The group, recently signed by Columbia, was mixing jazz and rock in an exciting hybrid that would result, over the coming months, in several hit singles, most notably “Spinning Wheel,” which reached as high as number two on the Billboard chart.

I must say that the idea of Thelonious Monk recording with Blood, Sweat & Tears strikes me as a pipe dream. After all, Monk created friction when he recorded with Miles Davis and other jazz legends—so how was he going to collaborate with a rock band?

But this plan wasn’t as bizarre as it seems at first blush. Consider the fact that Monk’s trusted manager Harry Colomby—who helped turn the pianist into a star over the course of a 14-year-partnership—was brother to Bobby Colomby, the drummer for Blood, Sweat & Tears. Monk might have agreed to the project, if only as a favor to Harry.

To strengthen the relationship, Blood, Sweat & Tears started asking concert promoters to put Monk on the same bill with them during a subsequent tour. I note that this happened when BS&T was at peak fame, and could bring Monk’s music to the attention of millions of young fans.

On their 1970 album Blood, Sweat & Tears 3, the band even incorporated a snippet of Monk’s composition “I Mean You” into their chart for the track “40,000 Headmen.” You can hear it right before the two minute mark—and though it doesn’t last long, the Monk theme works much better in a rock context than I would have anticipated.

Meanwhile the label plotted behind the scenes—producer Teo Macero got assigned a budget of $3,500 for a session bringing Monk together with Blood, Sweat & Tears. The marketing department started to plan an album cover, with guidance that it should be “ “something Psychedelic—way out.”

And then—when the stars finally started to align—Monk and the rock band got on the same stage. In March 1971, Monk agreed to serve as opening act for BS&T at Lincoln Center and the Coliseum in D.C. The idea that the high priest of bop (as Monk was sometimes called) would stroll out from backstage and sit in on piano during the rock band’s set might seem highly unlikely. But Monk often did unpredictable things—although not this time.

Nor did the planned recording session ever take place. The conventional view is that Monk would never have agreed, under any circumstances, to make a record with rock musicians. And perhaps that’s true. But the larger fact is that Monk never participated in another studio session of any kind for the Columbia label after this juncture.

Just getting him to compose a new song was almost impossible at this late stage in his career. The idea that he would reinvent his entire style, much like Miles did with Bitches Brew, was unrealistic. After those brief encounters on the same bill as BS&T, Monk would live more than a decade. But, for all intents and purposes, his legacy was secure, and his role in the history of American music fully defined. He had nothing to prove, and zero interest in spurring another revolution—whether from an underground bunker or the safer confines of the baroness’s house in Weehawken, NJ, where he spent his final years.

Even so, I find myself charmed, to a surprising degree, by the notion of what might have happened if Monk had been a little healthier and willing to go into the studio with a horn-driven young rock band. I tend to be skeptical of older musicians chasing after a crossover audience, but I’m probably all the more fascinated in this instance, because Monk would have have forced those young rockers to chase after him. He might have created some kind of fusion, but of a type for which only Monk himself knew the recipe.

And that’s exactly why I would have loved to hear Monk collaborating with a rock band. He would have forced them out of their comfort zone, and into something wild and beyond their expectations. Monk hardly needed that, because he already operated in that outré realm. But the top 40 commercial music scene could have used a big dose of his unpredictable intransigence, especially as rock struggled to find a new identity in the 1970s.

That’s my vision of Blood, Sweat, Monk & Tears—which would have been my name for the album. As such, it was a grand missed opportunity. Not for Monk, but for the rest of us.

A few comments: I had heard that at one time Columbia wanted Monk to do an album of Beatles covers - bizarre as that sounds! This was the second incarnation of BST of course, it was founded by Al Kooper and he was ejected after "Child is Father to the Man". And the Hal Willner Monk tribute album "That's the Way I Feel Now" demonstrates that Monk's music can work very well in a rock context! Thanks for the interesting article on one of my jazz heroes! ... N

BTW, there's an interesting photo floating around of David Clayton Thomas from BST jamming with Frank Zappa in Toronto in that era, so those guys definitely got around!