My book Music: A Subversive History appeared in paperback just 6 days ago. Below is an extract as a special feature for subscribers. Feel free to share with a few friends.

The Origins of Country Music in the Neolithic Era

by Ted Gioia

Many years ago, I noticed a puzzling pattern during my research into the music of herding societies. Cultures with no direct contact with each other had embraced strikingly similar musical practices and values. I could hear it in the style of their songs, in their choice of instruments, even in their attitudes about the role of music in everyday life.

I had just completed a comprehensive survey of hunting economies and their songs, and the contrast could hardly have been more sharply delineated. Herding communities in every part of the world had renounced the musical practices of their hunting ancestors and opted for a completely different body of techniques and platforms for expression. Was this just happenstance, or did the shift from hunting to herding in the Neolithic age fundamentally change musical practices—perhaps in ways that still impact our songs today?

Seeking guidance, I contacted a leading ethnomusicologist who had undertaken fieldwork in a current-day herding community and pressed him for answers. How did he account for these similarities and convergences? He had spent a considerable amount of time in one of these herding villages and had firsthand knowledge I lacked. What did he see as the connection between livelihood and music in these societies?

Rather than answering my question, he showed some irritation at it. Musical cultures were unique and incommensurable, he indicated, and generalizations of the sort I was pursuing failed to respect this fact. To explain one person’s song by looking at another individual across the world in a different context and community was a dangerous methodology, and ought to be discouraged.

The irony of this encounter only became apparent to me later, when I concluded that the similarities in the music of herding societies had nothing to do with people. It was determined, in large part, by the animals. Herders around the world had become adept at performing songs that soothed their livestock. By the same token, they avoided music that agitated the animals. Even today we use the term pastoral music—its etymology literally tells us that it is music for herding—to refer to gentle, relaxing sounds that summon up images of the pastures, soundscapes that evoke nature or rural settings.

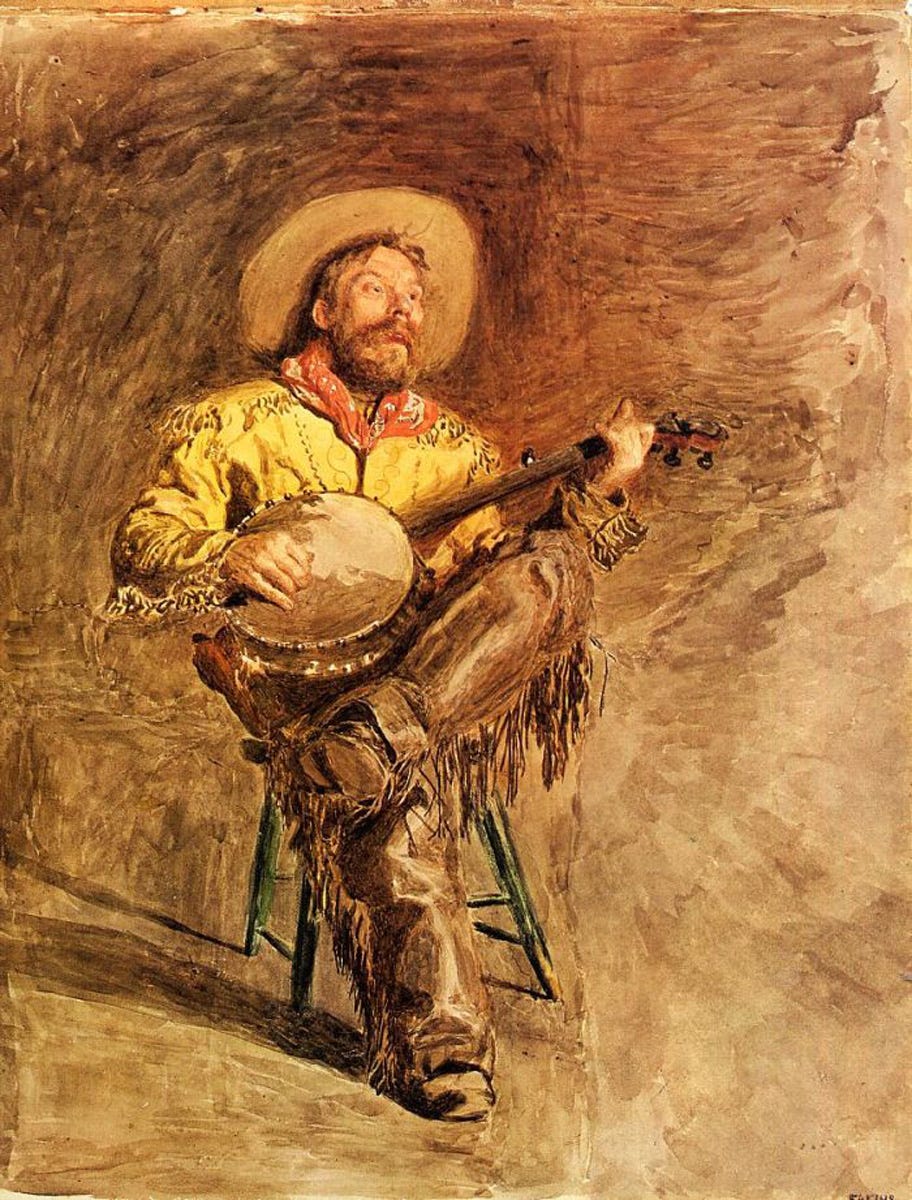

Musicians in these settings do not favor drums; instead, we find string instruments and plaintive wind instruments, such as panpipes and flutes. The music rarely channels aggression, but more often calms and subdues. These performers bequeathed that tradition to later generations, even those who abandoned the herding profession. Without the legacy of the shepherds, there would be no Pastoral Symphony from Beethoven, and perhaps no country music either.

Once you grasp this, it seems so obvious. And so many otherwise inexplicable choices and traditions are suddenly clarified. Yet even experts immersed in the music of the herding communities can fail to understand it—if their ideology is so rigid that they refuse to look beyond their own pasture.

“For many years, the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville went so far as to impose a formal rule prohibiting the use of drums in performance.“

Hunting societies had very different musical needs. If renegade historian Joseph Jordania is correct, our hunting ancestors were primarily scavengers and relied on loud, boisterous music to scare away other predators. Their music is more assertive, more aggressive, more likely to rely on drums and other declamatory instruments. We have inherited these practices as well. It’s perhaps an oversimplification to say that country singers are herders, and rock stars are hunters. But there’s an important truth here that deserves recognition.

We have nurtured two sharply contrasting musical cultures over thousands of years. One celebrates conciliation and the settled life of the rural world, while the other revels in the nomadic triumphs of the fierce and passionate human predator. (Recall, in this context, that the two dominant theories for the origin of music link it, respectively, to love and violence—and consider that these hypotheses may not be incompatible, but mirror images of each other, explicable both in terms of aesthetics and body chemistry.)

Surviving documents from the long history of herding reveal how much music contributed to that way of life, not only shaping its emotional texture but also supporting its economic viability. In different times and places, these songs stood out for their comforting melodies. “Shepherds’ pipes bring rest to the flocks in the pasture,” announced Macrobius, a Roman writer of the fifth century. In his studies of medieval herding practices of more than five hundred years later, historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie notes that “a flute was a necessary part of every shepherd’s equipment, and of one who was ruined it was said that he no longer had even a flute.” In more recent times, cattle herders and cowboys in the American West learned to rely on soothing songs to control livestock long before this vocal tradition got turned into a music-industry genre.

During the course of the twentieth century, country music grew into a multibillion-dollar business, but the herder’s marked animosity to drumming remained. For many years, the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville went so far as to impose a formal rule prohibiting the use of drums in performance. Long after electric guitars and rock-influenced acts found their way onto this venerable stage, musicians still had to fight for even a simple snare drum, and stories are told of drum kits played behind curtains to protect the delicate sensibilities of (no, not the cattle now) the audience.

Even superstars were forced to change their arrangements to please their persnickety Nashville patrons. When Carl Perkins enjoyed a huge hit with “Blue Suede Shoes” in 1955, the Grand Ole Opry had no qualms featuring this spirited rock ’n’ roll tune, provided the band’s drummer stayed at home. Country music eventually made its peace with the drums, but even today if you listen closely you will hear the rhythm guitar still driving the beat on many Nashville tunes while the drummer keeps a low profile in the background. Long after the cows have come home, to reverse an old proverb, we still seem to match our countrified music to their tastes.

“It’s perhaps an oversimplification to say that country singers are herders, and rock stars are hunters. But there’s an important truth here that deserves recognition.”

Even the lyrics of country music seem to have their roots in the Neolithic period. Country music still adheres to the ethos of settled life that entered human society with cultivating and herding—in sharp contrast to the nomadic imperative of hunting and gathering societies. You couldn’t wander very far if you wanted to raise a crop while breeding livestock. Maybe that’s why country songs still celebrate static lives, sticking with your job 9-to-5, even if it’s lousy, and standing by your good-for-nothing man, even if he’s worse. Blues songs are different. They deal with ramblers leaving on the next train and evading the hellhound on their trail, but that’s not country music. In country, you endure and abide, make the payment on the dented pickup truck, and go back to that same sad bar you went to last week, last month, last year.

That’s also true on the macro level: country first gained commercial success as the preferred music genre of those who refused to participate in the migration to the cities. Tens of millions of Americans left rural life behind during the course of the twentieth century, looking for new opportunities and ready to shed the traditional values of their origins. They ended up in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, Detroit, and other bustling urban centers. Those folks were never the core audience for country music. Eventually, demographics prevailed, and country music became citified. But that didn’t change the ethos of the genre, which still held fast to time-honored values and viewed urban trends with a large dose of skepticism.

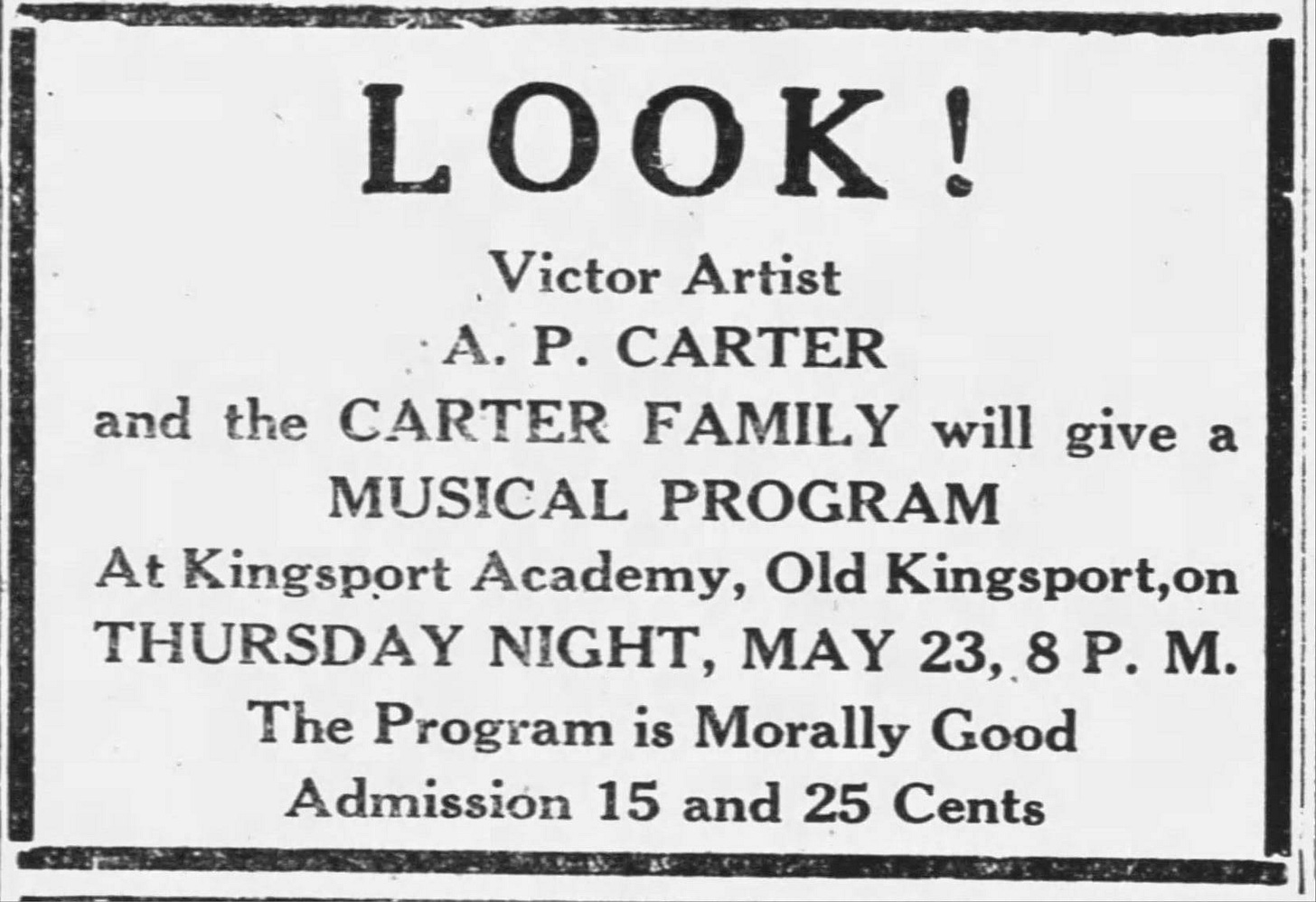

When the Carter Family brought their popular touring show of country music to town, the poster announcing their performances declared: “The Program is Morally Good”—a promise never made, since the beginning of time, by any famous blues band. The sober singing style of Sara Carter, purged entirely of the sensual sonorities of a Bessie Smith or Billie Holiday, reinforced the message. Buy your admission ticket, and leave your lust behind. Later country stars didn’t always live up to this standard in their private lives, or their public personas, for that matter, but the connection between this music genre and a settled, traditional way of life has never been completely sundered.

A direct historical lineage can be constructed tracing today’s country music back to the rural folk music of the distant past. There’s a good reason why British folk song collector Cecil Sharp came to the Appalachian region of the United States. “The people are very interesting, just English peasants in appearance, manner and speech,” he explained in a 1916 letter from North Carolina. “Their songs are marvelous. I have only been here 17 days and I have collected between 90 and 100 songs. Many have long since become obsolete in England.” Representatives of the music industry journeyed to this same region a decade later in their search for country recording stars. And the songs they found here retained some of the most distinctive elements of Old World herding music.

“Maybe that’s why country songs still celebrate static lives, sticking with your job 9-to-5, even if it’s lousy, and standing by your good-for-nothing man, even if he’s worse.”

Yodeling, for example, has been employed by herding communities for more than a thousand years, both as a call to animals and as a communication tool that reaches across pastureland to nearby villages. It’s a charming sound, with its alterations between low chest tones and high-pitched or falsetto notes, but not really a song in any true sense of the term. Yet yodeling started showing up on country records almost from the start. We hear it in the recordings of Emmett Miller, Riley Puckett, and especially Jimmie Rodgers, who turned it into a trademark of his down-home country style. “Everyone who could pick a guitar” was soon yodeling like Jimmie Rodgers, according to musician Herb Quinn, who performed in Mississippi in the 1920s. The music was now popular entertainment, no longer a functional tool in the management of livestock, but its pastoral origins still reverberated in the radio hits.

Make no mistake, however: the country genre from the very start was more than just a revival of old folk songs. Talent scout Ralph Peer offered what might be the best description of the difference between the two idioms. When a researcher approached him late in his life, seeking to find details of Peer’s advocacy of new music genres, the veteran producer claimed that he had been seeking out “future folkloric songs.” Country music fans may have celebrated the values of the past, but they always demanded new songs. This craving for novelty created an inevitable rupture with folk musicians, who had a “greatest hits” mentality long before that became a music-industry album concept. Folk singers wanted to live off the back catalog (as we might describe it nowadays), not create new songs. As such, they were less adept at dealing with the music business, which constantly needs fresh material to peddle, than this new breed of country singer. “I made it a rule,” Peer clarified in his letter, “not to use any artist for a recording who could not compose.”

Perhaps you are surprised—or even dismayed—that country singers can keep on writing new songs about the same old subjects for going on a century, and never lose their audience. But recall that constant reassertion of old values is the modus operandi of traditional societies. The weekly homily from the pulpit isn’t supposed to break new ground. The blueprint for down-home living isn’t a future utopia—it’s holding onto the good ol’ days. But country music’s ability to survive the urbanization and suburbanization of America is nonetheless a puzzling phenomenon.

Country was the first lifestyle music, and was marketed that way a full generation before the strategists at the Rand Corporation invented lifestyle marketing. In fact, that brand-building strategy shaped the image of country music long before the word lifestyle entered the English language. But how do we explain the puzzling anomaly that country music not only survived but actually thrived even as herding and cultivating lifestyles disappeared from the economy? Perhaps that was the real stroke of genius behind the marketing of country music: the realization that lifestyles are about projecting a fantasy, not living in reality.

From this perspective, our favorite songs and genres are less a mirror to our actual life, and more like photoshopped images presenting the life we wish we led. So just as cunning minstrels still sang about knights and their oaths of fealty long after the collapse of feudalism, country singers celebrated a world in their music that had disappeared, or in many cases never existed, for most of their listeners. The pick-up truck must symbolize the horse that never was; and instead of rounding up the cattle, you just grab a six-pack from the fridge.

And in this way, too, the country audience was staying true to their Neolithic ancestors. Recall that the rupture of the Neolithic revolution wasn’t really inspired by a love of farming or herding; it was driven by the preference for a stable, settled life, despite its boredom and repetition, over the risky, rambling ways of the nomad. From that perspective, country music is perhaps relevant even in a high-tech digital age, all the more so if our new technologies seem disruptive or threatening.

The above is an extract adapted from Music: A Subversive History (Basic Books).

So insightful and interesting. Thank you for the effort and real work demonstrated here Ted!

Fascinating. I couldn't help but make a political connection as well. It's been said that in America the older generations are predominantly Republican, a party that celebrates this settled lifestyle. I'd expect other societies politics to mirror that trend. As people age they often feel vulnerable and less adventurous and more connected to religious practices hoping for an afterlife. Further, with the rise of country music's popularity there's been a corresponding rise in "conservatism." Gun ownership is politically divided and a gun is viewed as a method of protection, etc....

I always find your writing draws me away from my daily routine and gives me a different perspective. Thank you.