The Only Instrumental Record Ever Banned by US Radio

Guitarist Link Wray belongs in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame—if only for recording the most feared guitar instrumental in American music history

I can’t figure out why Link Wray isn’t in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Of course, there’s much about that organization that’s mystifying, but especially the criteria for admission. It often seems little more than a popularity contest, similar to my old school’s gossipy and backstabbing approach to choosing the Homecoming Queen.

Rock and roll deserves better.

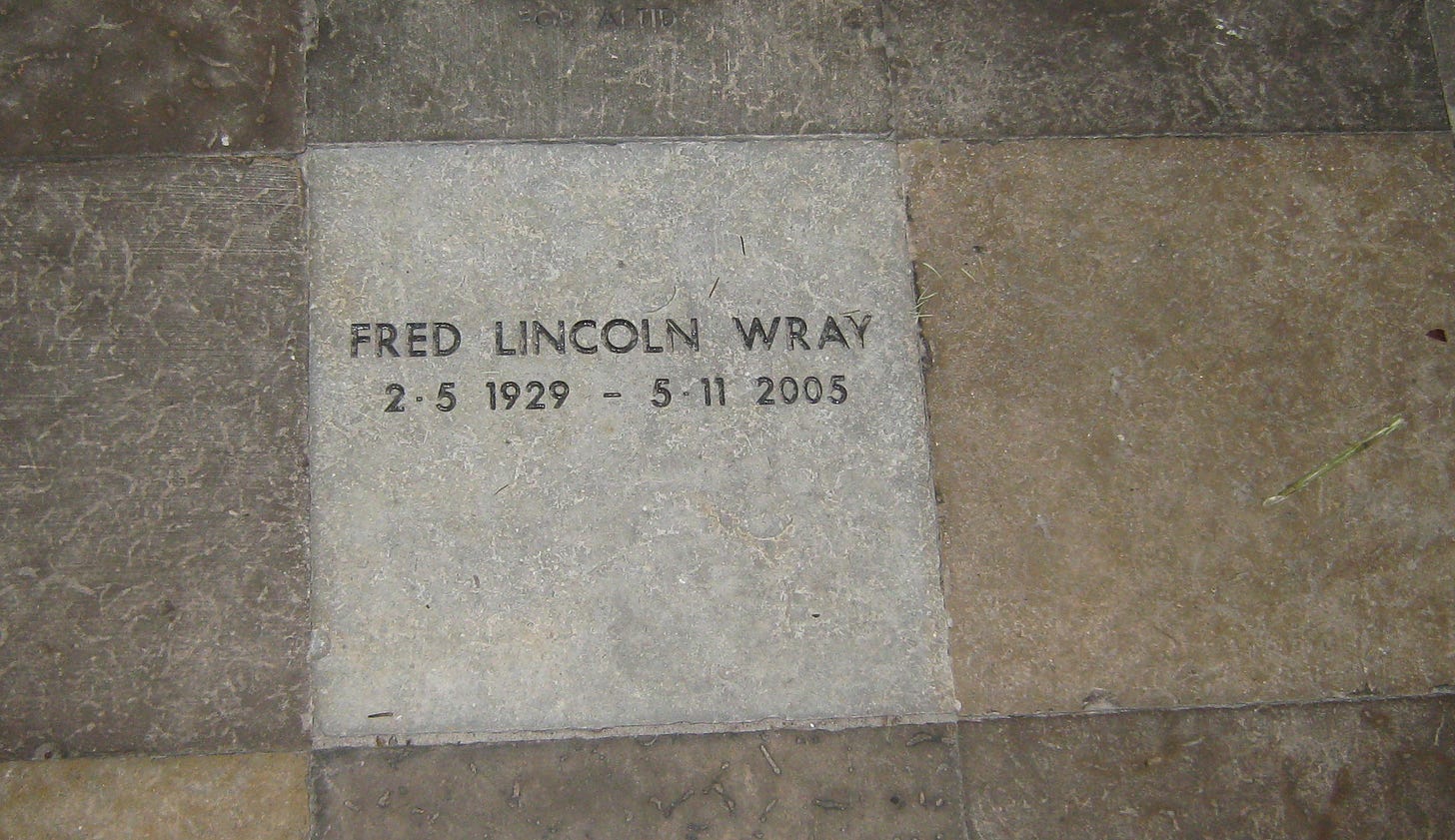

And so does Link Wray, who is poorly equipped to win a popularity contest. He’s come close—Wray was twice nominated for the Hall of Fame (in 2013 and 2017)—but never close enough. And even the few honors he has enjoyed, mostly arrived after his death in 2005. During the 76 years he walked (and rocked) on the planet, Wray was usually taken for granted—that’s when he wasn’t totally forgotten.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

In his 2005 obituary, The Guardian noted that the British Invasion in rock had “rendered Wray obsolete”—although they quickly added that John Lennon admired his guitar work. They pointed out that he recorded many of his best tracks in the “family chicken coop” and had played his music in “America's grimmest bars and clubs.”

But ten years after his death, Rolling Stone featured Wray on their list of the greatest guitarists of all time. And in 2017, Wray’s “Son of Rumble”—a follow-up to his most famous song—was finally released, albeit 47 years after it was recorded. Around that same time, Wray earned one last posthumous (and unsuccessful) nomination for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I doubt he will get another chance.

As a consolation prize, the Hall gave recognition to Wray’s influential track “Rumble” as part of a new policy of honoring hit songs, even as the guitarist himself failed to make the cut.

In truth, his name recognition is modest. That’s true even among rock fans—many know about other pioneers of the genre (Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, etc.), but ask them about Mr. Wray, and you may only get a blank stare.

Maybe if they had made a movie about him, akin to La Bamba or Great Balls of Fire! or The Buddy Holly Story , fans and critics would rally to his cause. But there is no Link Wray biopic (although this documentary is a step in the right direction).

That’s strange too. The Link Wray story would make for a riveting film. A Native American child, Shawnee on his mother’s side and Cherokee on his father’s, Wray grew up during the Great Depression in constant struggles with poverty, when he wasn’t fearing the more immediate threat of the Ku Klux Klan. The family would hide, or put blankets over their windows, when the cross burning started.

"Elvis, he grew up white-man poor,” Wray once told an interviewer— “I was growing up Shawnee poor." And even as a young man, he seemed destined to follow in the unfortunate footsteps of his father, who had suffered shell-shock in World War I, and never managed to find his way, surviving through poorly-paid farm work and street preaching.

During his twenties, when most up-and-coming musicians are making their reputation, Link Wray was fighting in Korea. He left the military after three years without medals or honors, but also missing one lung, lost to tuberculosis. At first Wray thought he would die, and might have without emergency surgery. He survived, but the medical prognosis ruled out any postwar career as a singer—although Wray would overcome those stacked odds.

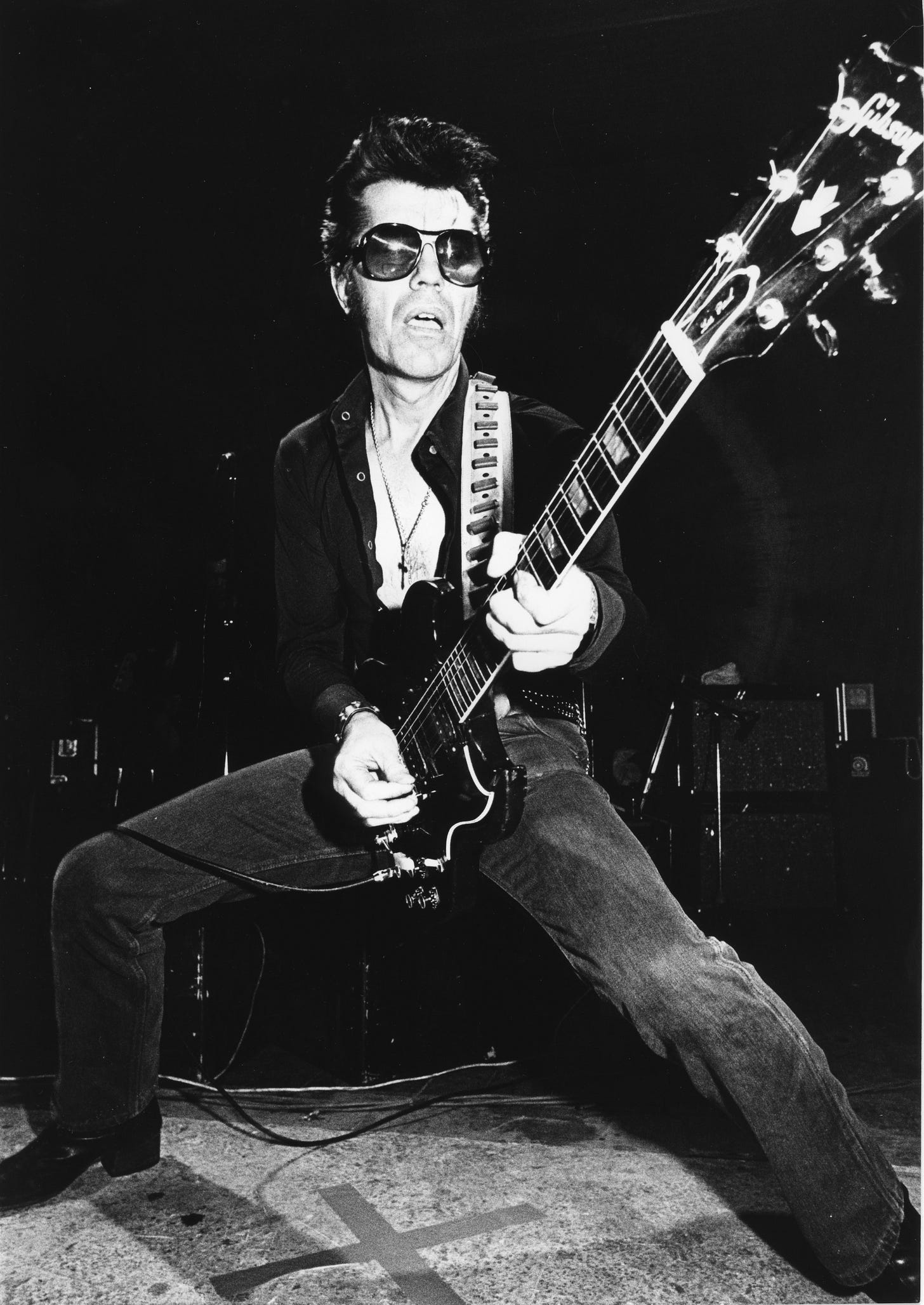

But nothing could constrain his mastery of the guitar, and he developed into one of the most distinctive players of his day—not so much a soloist, as a kind of musical wizard stirring up a cauldron of electric sound. You might even say that Link Wray is the quintessential rock guitarist.

Bob Dylan, who was inspired by Wray as a youngster, allegedly told him over dinner that he was better than Hendrix. Pete Townshend of the Who once claimed that "If it hadn't been for Link Wray and 'Rumble,' I never would have picked up a guitar." Bruce Springsteen has played “Rumble” in concert. Other ardent Link Wray fans include Jimmy Page, Neil Young, and Iggy Pop.

But film directors have done even more than the music establishment to ensure Wray’s lasting renown. Quentin Tarantino featured two of his songs, “Rumble” and “Ace of Spades,” in Pulp Fiction. Wray’s “Jack the Ripper” shows up in Robert Rodriguez's Desperado, as well as the 2019 Oscar Best Picture nominee Ford v. Ferrari. I recently heard “La De Da” on the TV show Barry. Filmmakers especially love “Rumble,” which has also appeared everywhere from Independence Day to The Sopranos. If you want to convey a sense of rebellion or menace with just a snippet of music, Wray is an inexhaustible resource.

None of this should surprise you. Those seeking for the spirit of rock guitar in old vinyl grooves, will find there’s no better place to start than Wray. And though he had few genuine hits—another reason he isn’t enshrined in that Hall of Fame—his legacy of recordings is formidable for anyone who grasps the inner essence of the rock idiom.

Wray got his love of the guitar from a black circus musician, who used the bluesy bottleneck technique that bent notes and distorted tones in ways that anticipated the later rock revolution. “I heard him playin’ that bottleneck music,” Wray later reminisced about this decisive visit to the local circus, “and I knew right then I wanted to play a geetar. I mean I wanted to play country music, black music, bottleneck music—I wanted to play it all.”

And eventually he did. Like the bottleneck player who first inspired him, Wray learned how to master a wide range of rude, distorted sounds. He may not have invented the power chord—that in-your-face root, fifth and octave that is more a jolt to your central nervous system than a genuine harmony—but he played it with unsurpassed gnarliness, and thus laid the foundation for so many later rock, metal, and punk guitarists.

"We played rock 'n roll ten years before it was given a name,” Wray once boasted. I can’t prove he’s right, but judging by the surviving recordings, it’s a plausible claim.

Other musicians have had songs banned from radio, but only Link Wray managed to get censored for an instrumental number. This tells you how unsettling his aesthetic vision was at the close of the 1950s. “I guess you'd call my stuff really dirty and menacing,” he once told an interviewer—but he was quick to add: “The spirit of rock and roll is like any church. I’m very spiritual. I give all my credit to Jesus God.”

That menacing song was “Rumble,” just two-and-half-minutes long, and there wasn’t much churchifying in it. “Rumble” is a peculiar track by any measure. You might think that an instrumental banned as an incitement to violence would be fast and raucous, but “Rumble” is slow and hypnotic—the tempo is under 100 beats per minute.

I take seriously the physiological correlations of songs and body states, so let me note that this is the same rate as a human heart in a state of slight anxiety—in other words, it’s slow for a hit single, but dangerous for your cardio metrics.

The song happened by sheer chance—when Wray and his band tried to come up with a backup groove for the hit song “The Stroll,” a popular slow dance number of the era. But instead they created an impromptu instrumental that energized listeners, a piece they originally called “Oddball,” but later became “Rumble.” The first time they played it in live performance, at Fredricksburg, Virginia in early 1958, the audience insisted on four encores.

The guitar sound on the track is riveting. According to legend, Wray had to poke a hole in the cone of his amp to get the dirty fuzz tone that set this song apart. To add to the intensity, a vocal microphone was placed in front of the guitar amp. This was necessary not merely to grab the audience’s attention, but also to get Wray’s guitar sound loud enough to eclipse the drums, played by his brother Doug—who was, according to his sibling, the loudest drummer in the world.

This new song had the makings of a hit, at least judging by the response of rebellious teenagers. Record industry execs, in contrast, hated it. Archie Bleyer of Cadence Records only released “Rumble” because his stepdaughter liked it. The name came from Phil Everly who said that the raw sound of the track reminded him of a street fight.

He wasn’t the only person who linked Wray’s song to juvenile crime—although you might think the name simply referred to how your sound system’s speakers rumbled when you put this record on the turntable. Many listeners could only hear“Rumble” as a clarion call to gang violence and vandalism. By any measure, it possessed a dark, ominous quality, unlike anything else on the airwaves. As a result, “Rumble” was eventually banned by many radio stations, who felt that, even in an age of rock ‘n’ roll, this single went too far.

That only helped sales. “Rumble” would break into the top twenty, and eventually sell some 4 million copies. Wray’s attitude and persona on-stage—where he postured and strutted in sunglasses and black leather—added to the counterculture vibe of the song. He dressed for concerts as if he were going to a brawl, and it was often a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“People would pull out their knives and cut each other,” he admitted in an interview. “I'd take a break and go outside and the police would come and carry 'em all out and I'd go back in and play again.”

Wray released follow-up songs with even more threatening names (“Jack the Ripper,” “Switchblade,” “The Outlaw,” etc.), but he would never enjoy a bigger hit. His fans, however, maintained their devotion, even as the mass-market audience soon moved on to other styles and trends. Wray found work in rock revival settings, and as a pioneer of the rockabilly sound, continuing to sell records and draw crowds. When asked about the violent associations of his most famous song, he’d reply: “I’m wild but I’m not evil.”

And that record still sounds wild, even so many years after Wray’s death. But that’s the wildness at the heart of the greatest rock music. We shouldn’t forget it nowadays, when a formerly formidable genre is turning into a soundtrack for nostalgia and reminiscences about so-called good ol’ days.

Maybe “Rumble” is exactly what we need as a reminder of what this music is really all about. And perhaps the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame needs a reminder too, that they’re long overdue in enshrining the man who captured that spirit, teaching so many others to rumble in his wake.

I had the great pleasure of meeting him when he and Robert Gordon were touring together. Spent half an hour backstage with them before the show. Couldn't have been more friendly and polite.

Probably one of the 10 best shows I ever saw. He did Ruble for an Encore and it literally brought tears to my eyes. My black lab is named Link.