The Most Cynical Novel Ever Written

After 90 years, Journey to the End of the Night is still a bitter pill to swallow

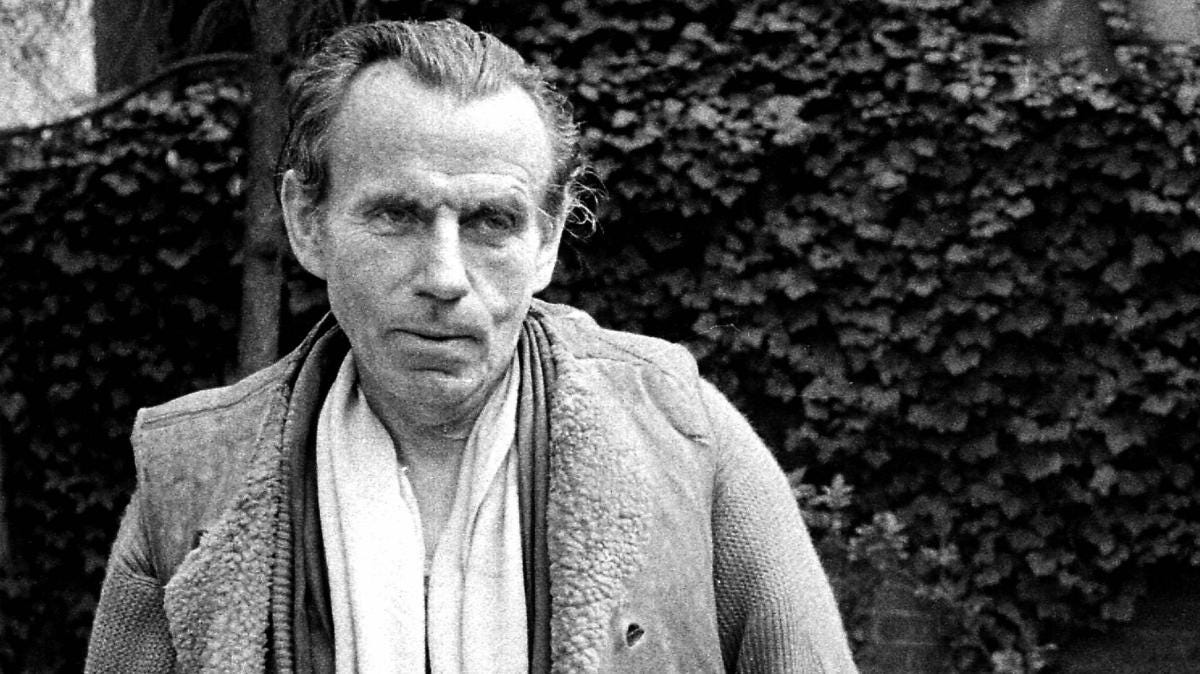

If you labeled Louis-Ferdinand Céline on the basis of a quick perusal of his professional resume, the words that come to mind might include humanitarian, diplomat, and altruist.

You would note that he worked for the League of Nations, an organization that promoted world peace at a juncture in history when armed confrontation was the norm. You would applaud his efforts, under the sponsorship of the Rockefeller Foundation, to improve hygiene and halt the spread of tuberculosis. You would see that he had received a medal for bravery in World War I, had treated the poor as a medical doctor, and led a campaign to improve working conditions for factory laborers.

What an admirable individual, no?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

But how do you reconcile all this with Celine’s literary masterwork, the semi-autobiographical novel Journey to the End of the Night? I would stake a claim that this 1932 book ranks as the most cynical novel ever written. Only a misanthrope could write a story of this sort, or perhaps an embittered nihilist. His philosophy as a writer can be summed up in the simplest terms: If you don’t have something good to say about somebody, you need to put it in a book.

But that’s not why Céline is so controversial today. “I have French friends who point-blank refuse to read Céline because of the antisemitism,” notes novelist Tibor Fischer. When France’s Ministry of Culture decided to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Céline’s death in 2011, such a ruckus ensued that minister Frédéric Mitterrand was forced to cancel the plans—although a number of French intellectuals denounced the move as a bow to censorship.

“Is Céline just one more misanthropic author? There’s no shortage of them, and the French have an especially strong claim to this category, from Voltaire to Flaubert to Michel Houellebecq.”

Céline’s enthusiasm for the Nazi occupation of France during World War II was so extreme that he was forced to flee to Denmark after the end of the war, and was convicted in absentia as a collaborator in 1950. He was pardoned in 1951, and returned to France without serving the judge’s one-year sentence. His views on political matters were both controversial and outrageous. He once claimed that both Pope Pius XII and Hitler were Jewish, and on another occasion stated that Hitler had been replaced by a stand-in. (Some critics responded that Céline himself must be Jewish, and writing such drivel in order to show how crazy antisemitism had become.)

But Céline anticipated all of this years ago. In the preface to his 1944 book Guignol's Band, he proclaimed: “I annoy everyone.” But that admission provides little comfort. And the recent rediscovery of two suitcases of the author’s lost manuscripts has again raised all the divisive issues related to this troubling figure.

What do you do with a problem like Céline?

He lives up to this pledge to annoy on almost every page of Journey to the End of the Night. Our protagonist, coincidentally named Ferdinand, scorns everything he encounters, and no one is exempt from his derision—whether politicians, generals, and other authority figures, or the workers and stragglers at the opposite end of the social hierarchy. Each has a part to play in the dismal charade of society, that depressing journey to the end of the night.

Is Céline just one more misanthropic author? There’s no shortage of them, and the French have an especially strong claim to this category, from Voltaire to Flaubert to Michel Houellebecq. But, in all fairness, the British can boast of their own candidates: Swift, Larkin, Naipaul, Amis (both father and son), etc. Americans have a hard time living up—or down?—to these standards, but some of Twain’s work and the later writings of Saul Bellow might qualify for inclusion in a misanthrope’s anthology. These are authors you might read, but do you really want to sit down with them and chat over a pint of beer?

“This book is the antithesis of the safe space—every page earns a trigger warning.”

Yet, in a strange way, Céline has written a kind of topsy-turvy picaresque novel, with surprising similarities to the other French works in this genre, such as Lesage’s Gil Blas or Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel. The term picaresque derives from the Spanish word picaro, referring to a rogue or scoundrel, but usually an affable one whose exploits and chicaneries delight the reader. And Céline, like Rabelais, takes us on a series of disparate and discordant adventures that include war, romance, travel, amusements, and libations.

But, in every one of these instances, Céline probes the dark underside of the adventure at hand. The opening pages, which deal with Ferdinand Bardamu’s exploits in World War I, include some of the most caustic passages ever written on the brutality of human conflicts, all infused with a sardonic humor than anticipates Joseph Heller’s Catch-22—I’m hardly surprised that Heller cited Journey to the End of the Night as a major influence on his work. (In a 1975 interview, he noted that the opening lines of Catch-22 came to him while “lying in bed, thinking about Céline. . . . The next morning, at work, I wrote out the whole first chapter and sent it to my agent.”)

The anti-war sentiment is so potent here, that we assume a return of peace will improve our protagonist’s prospects and attitude—but that’s hardly the case. In subsequent sections of the book, the narrator travels to Africa, the United States, and then returns to France, where he works in a variety of capacities, as a doctor, as a stage performer, and finally as an administrator of a mental asylum. In every instance and setting, Bardamu encounters fatuity, injustice, and greed.

The degradation of the human condition is epitomized in Ferdinand’s acquaintance Robinson—an individual who seems to show up everywhere our protagonist turns. We run into Robinson on the battlefield, in the heart of Africa, in the United States, and then back in France. He is a despicable character, narcissistic and distrustful, capable of the worst crimes, including murder. Ferdinand comes to hate his alter ego, and tries to avoid getting caught up in Robinson’s various schemes and entanglements. But that can’t hide the fact that the two are almost doppelgängers. The very traits Ferdinand dislikes in Robinson are those which he could find, without much difficulty, just by looking in a mirror.

Journey to the End of the Night is a powerful book, but more for its bravado and incidents than its plot and structure. I don’t complain about the discombobulated story line—after all, the great picaresque novels, even the masterpieces by Cervantes, Fielding, Rabelais, and Sterne, wander far and wide over the terrain. I am more put off by the author’s inconsistent tone. In the opening section, Céline wavers between mordant realism and satire, but one-third of the way through the book, when his protagonist travels to America, the book adopts an absurdist tone—Ferdinand gets a job counting fleas on the bodies of newly-arrived immigrants. Then, in the biggest shift in the entire book, our hero has a touching romance with a self-sacrificing young lady—we almost feel like we have tumbled into a different novel entirely. But this doesn’t last for long, nothing does in these pages. In the final half of the book, Céline returns to the dark humor and cynicism that we have come to associate with this author.

These shifts are so abrupt, that the reader feels as if this book were stitched together from different manuscripts, each with its own distinctive worldview and symbolic resonance. The various sections might work individually, but fit together uneasily. Céline’s most famous work, for all its daring, remains a hodgepodge, a ragtag collection that never quite coheres.

But perhaps that is the expected end result when an author tries to build a long book on disdain, bitterness, and misanthropy. Those aren’t qualities that contribute to a holistic view of life. They don’t integrate anything, whether a career or a book.

Yet I can’t deny that Céline stayed true to his own vision. The same qualities that shaped his life—and led to prosecution, exile, manias, and babblings that sometimes bordered on incoherence—are precisely the ones he drew on in his writing. He wrote exactly the kind of books that a man of his bent was destined to write.

In the current day, novels of this sort are considered problematic. Maybe even removed from shelves. This book is the antithesis of the safe space—every page earns a trigger warning. But sometimes we learn the most from works that share exploits and viewpoints we might not genuinely grasp, in all their danger, it they were suppressed.

You ignore the dark side at your own risk. A world in which barbarism and extremities are scrupulously hidden from view is actually a much more dangerous place. Even though I find parts of this book disagreeable, I’d still consider assigning it in a college course—and for that very reason.

Let me put it differently: Without a Journey to the End of Night we might never genuinely appreciate the clarifying dawn. For my part, I’m grateful that I can experience Céline’s mental state through his novel, without having to live inside it. And when I feel inclined to condemn the author, I consider that this book’s poor deranged writer may not have had that choice.

Céline wasn't just a writer who uncompromisingly exposed the darkness that lies within human nature.

He saw himself simply as a stylist and always emphasized the effort that led him to achieve the desired literary effect. He was right about that, it's difficult to find anything comparable in French literature.

Style should not be entirely individual. Variations on classicism constitute virtually most of the history of French literature after the seventeenth century. Céline on his part created a completely distinct style that cannot be imitated. It accentuated his individuality, but it is completely sterile in the perspective of tradition: today no one will come and try to write like Celine. One may try to write like, for example, Paul Morand, and express himself in that style. By imitating Celine, one can at most create a pastiche, but not an original work.

In the harsh view of human nature that we find in Céline, we must also see a continuation of the French moralists. They had no pity for the human race, too.

Either way, French literature found in Céline a remarkable union of stylistic sophistication and exuberant temperament.

The best short piece I've seen which examines and explains a lot about the convoluted, contrary character known as Celine, concentrating on his writing style, was written by Kurt Vonnegut. It was published in the 1970s as an introduction to the Penguin editions of Celine's last three novels, the wartime trilogy of Castle to Castle, North and Rigadoon, and has been included in some Vonnegut anthologies.