The Many Missed Opportunities of Bola Sete

The almost famous Brazilian guitarist's best work has finally been released—more than three decades after his death

I’m finalizing my list of the 100 best recordings of 2021—which will go out to paid subscribers on Monday. Because of email limits, I will need to share it in two installments.

In the meantime, let me showcase one last new recording from 2021, featuring remarkable previously unissued tracks from Brazilian guitarist Bola Sete (1923-1987). Official release date is Friday.

Below is my account of the life and times of this sadly underrated musician.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The Many Missed Opportunities of Bola Sete

By Ted Gioia

Brazilian guitarist Bola Sete always made the right move—but at the wrong time. That could have been his motto, so fervently did he follow this unfortunate formula. As a result, he missed almost every chance for crossover fame, although he came close on several occasions. Given that track record, it’s somehow both sad and fitting that his most impressive recordings finally get issued almost 35 years after his death.

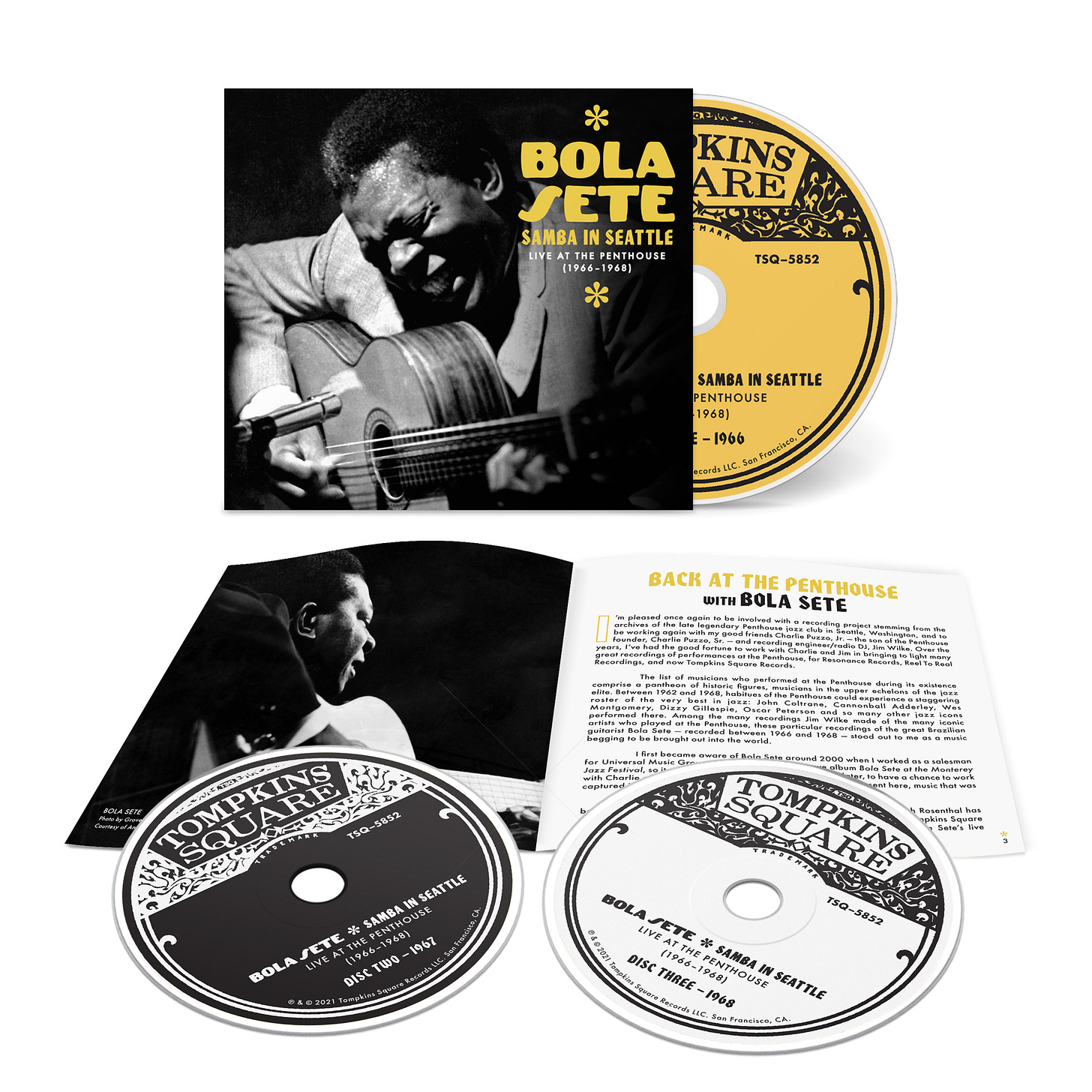

That release, Samba in Seattle, captures Bola Sete in live performance at the peak of his abilities in the late 1960s. This triple-CD box set, featuring some two hours of music, was recorded by the beloved Seattle jazz disk jockey Jim Wilke, and the recording quality is excellent, better than some of the guitarist’s studio albums for Fantasy. In other words, this is no bootleg—Wilke often set up multiple microphones onstage, and operated a mixing board near the piano. But the real attraction here is Bola Sete, who reminds us on track after track that some of the best Brazilian music of this era was recorded thousands of miles from Rio.

Bola Sete was born in that city in 1923 as part of a historic generation of musicians who would rise to global fame via the bossa nova sound. He was just a few years older than Antonio Carlos Jobim and João Gilberto, and was a standout guitarist even in a city famous for its exponents of that instrument. But even more than those illustrious contemporaries, Bola Sete could draw on his rich Afro-Brazilian ancestry and culture in creating songs and sounds well outside the bossa nova formulas.

His very nickname came from his racial heritage. His dark skin led to comparisons with the black 7 ball in snooker. As DJ Greg Casseus once quipped, if his friends had played billiards instead, the guitarist might have taken on the name Bola Oito. In Brazil, a country where celebrities often prefer nicknames over birth names, the new identity stuck.

For better or worse, Bola left for the United States in 1959, just at the moment that bossa nova was starting to reshape the musical soundscapes of his native country. This had all of the telltale signs that would mark his entire career—because, of course, moving to the United States was an obviously smart financial move, but leaving at the close of the 1950s meant that he missed the most significant Rio musical revolution of his lifetime. Had he stayed a few years longer, Bola could have participated, rather than viewed it from afar.

Yet these newly released live tracks of Bola Sete, recorded at The Penthouse in Seattle between 1966 and 1968, make clear that he was one of the finest bossa nova guitarists in the world at that juncture. His playing on song after song is a revelation, especially when performing unaccompanied—where every nuance in the music demonstrates his mastery. But it was Bola’s bad luck that this all happened at an interlude in his career when he had no record label.

Bola Sete was gigging at Sheraton Hotels in the US when bossa nova was taking off back home. He was under contract to that company for several years, and though he played in major cities, including New York and San Francisco, the setting was typically a hotel cocktail lounge, not a jazz club or concert hall. But here again, he came close to achieving crossover fame, when Dizzy Gillespie—a hotel guest—heard the guitarist and brought him to the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival. Bola created a stir at that event, but hardly at the level he might have achieved just one year later when every jazz record label was determined to sign Brazilian guitarists.

According to the Lord Discography, Bola and Dizzy only recorded together on three studio tracks—made on July 10, 1962. In November, Stan Getz’s recording of “Desafinado” would climb to number 15 on the Billboard chart, and officially launch the bossa nova craze in the US. Gillespie would later complain that he knew about this new Brazilian music even before Getz, but by then he had parted ways with Bola Sete, and both watched from the sidelines as bossa nova took over the airwaves.

Yet Bola’s next move also promised to be huge, and would have been, if only the timing had been better. The Brazilian guitarist now launched an exciting partnership with pianist Vince Guaraldi, and the two musicians demonstrated extraordinary musical chemistry. They had met at the Monterey Festival, and were so excited by their give-and-take, that they went into a recording studio within 24 hours of their first informal jam session at Guaraldi’s home.

Guaraldi had close ties with the Fantasy label, the largest indie jazz record company in San Francisco. This now became Bola Sete’s label, and the duo recorded three Fantasy albums between 1963 and 1965. Guaraldi, however, was destined for far greater fame, and started down that path almost immediately after splitting with Bola. In December 1965, Guaraldi’s soundtrack to A Charlie Brown Christmas was released—a perennial holiday album that would eventually go quadruple platinum. But Guaraldi relied on a piano, bass, and drums trio for most of that music, although I can easily imagine that Bola would have been involved if Guaraldi had been hired to do that same soundtrack a year earlier.

The parting between the two artists was friendly, and Bola was enthusiastic about leading his own trio. But he must have felt some regrets when he saw the acclaim and record sales that the Charlie Brown connection would bring his former bandstand colleague.

After his career took off, Guaraldi left the Fantasy label, signing a three-record deal with Warner Bros. It took a lot of finagling and a lawsuit to extricate himself from Fantasy, and the old label was certainly unhappy to see him move to a larger competitor just at the moment when he was reaching a new crossover audience. In the aftermath, Fantasy dropped Bola Sete from the label.

As a result, there’s a late-1960s gap in Bola’s discography—the period when these newly released recordings were made. And they make clear this was high point of his artistry. He sounds both relaxed and commanding on these tracks—more so than on the Fantasy albums, despite their many virtues—and I would recommend these as the entry point for any fan who wants to enjoy this musician at peak form. His bossa nova renditions are gems, and when he branches out into samba, semi-classical, or other stylings, it’s always with total authority. It’s unfortunate that these weren’t issued during his lifetime, when they almost certainly would have given a much-needed boost to his career.

Give a gift subscription to The Honest Broker this holiday season.

I could easily envision Bola participating in the major jazz movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s. He would have fit perfectly with the crossover projects pursued by the CTI label in that period. He also could have become a major force on the growing ‘world music’ scene—I fantasize about him playing duets with Ravi Shankar or Ali Farka Touré. Or he might have flourished with a jazz-rock fusion band, or as part of the chamber jazz movement taking off overseas.

But instead, when he returned to the studio, he recorded pop and rock covers. This was the low point of Bola’s career, but even these commercial tracks would gain posthumous traction, sampled and borrowed by DJs and hip-hoppers. His career ambitions appeared to wane at this time, and I hear of him practicing yoga and meditation, while enjoying home life with his American wife Anne Sete, after their 1969 marriage. She remembers him playing the guitar, during these years, while sitting in a full lotus position.

But the Bola Sete story wouldn’t be complete without one last chance at crossover success. Some of the instigators of the New Age movement were fans, and convinced him to reinvent himself and his guitar style. John Fahey, the eccentric protagonist of American primitive guitar, recorded Bola for his Takoma label in the 1970s, and an even bigger break came his way a decade later, when George Winston decided to produce an album featuring the Brazilian guitarist.

This happened at a time when Winston’s albums on the Windham Hill label were selling by the millions, first on the West Coast and then throughout the US, and finally overseas. This was a relationship that could have turned Bola into a huge star with a young audience. But Winston had already left Windham Hill at this juncture, and signed Bola to his own Dancing Cat Records. Even so, this could have been a breakthrough moment for the guitarist.

But even while working on this final album, Bola was battling the lung cancer that eventually proved fatal. He died on Valentine’s Day 1987, at age 63. Winston would continue to serve as an advocate of Bola Sete’s music, ensuring the release of several posthumous project, but none are as compelling as these Seattle tracks from the late 1960s.

Yet I fear that, even after his death, the rediscovery of this music won’t have quite the impact it deserves. In an age of streaming, how many people still buy these lavish box sets? Even more to the point, can Bola Sete really establish himself as a major exponent of bossa nova so long after that movement has faded from view? This should be a heralded release, but it’s likely to be treated as a footnote to his biography. So once again, good things happen for him at the wrong time.

Yet the music itself tells a different story, This is fresh, vibrant work, rewarding your attention even more than a half-century after it was recorded. I’d like to think that, for discerning listeners with big ears, Bola Sete’s time hasn’t really passed, but could be happening again, right now. He certainly deserves at least one lucky break.

Enjoying just music via Qobuz right now. Thank you, Ted!

I have one his albums with Vince Guaraldi on Fantasy. It's seems to be titled "Vince and Bola". Good music!