The Live Music Event That Changed My Life

I met my destiny, and nothing would be the same afterwards

I’ve occasionally mentioned that a visit to a nightclub in my teen years changed my life. Sometimes I’ve shared a few details, but I’ve never told the whole story.

But it’s worth telling. This incident had an earthshaking impact on me, transforming everything almost in an instant. Just knowing that these things are possible might help others—so I’ve decided to tell this tale in its entirety.

Many of us wonder how we find our own path in the world. This is the story of how it happened for me.

Please support my work by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

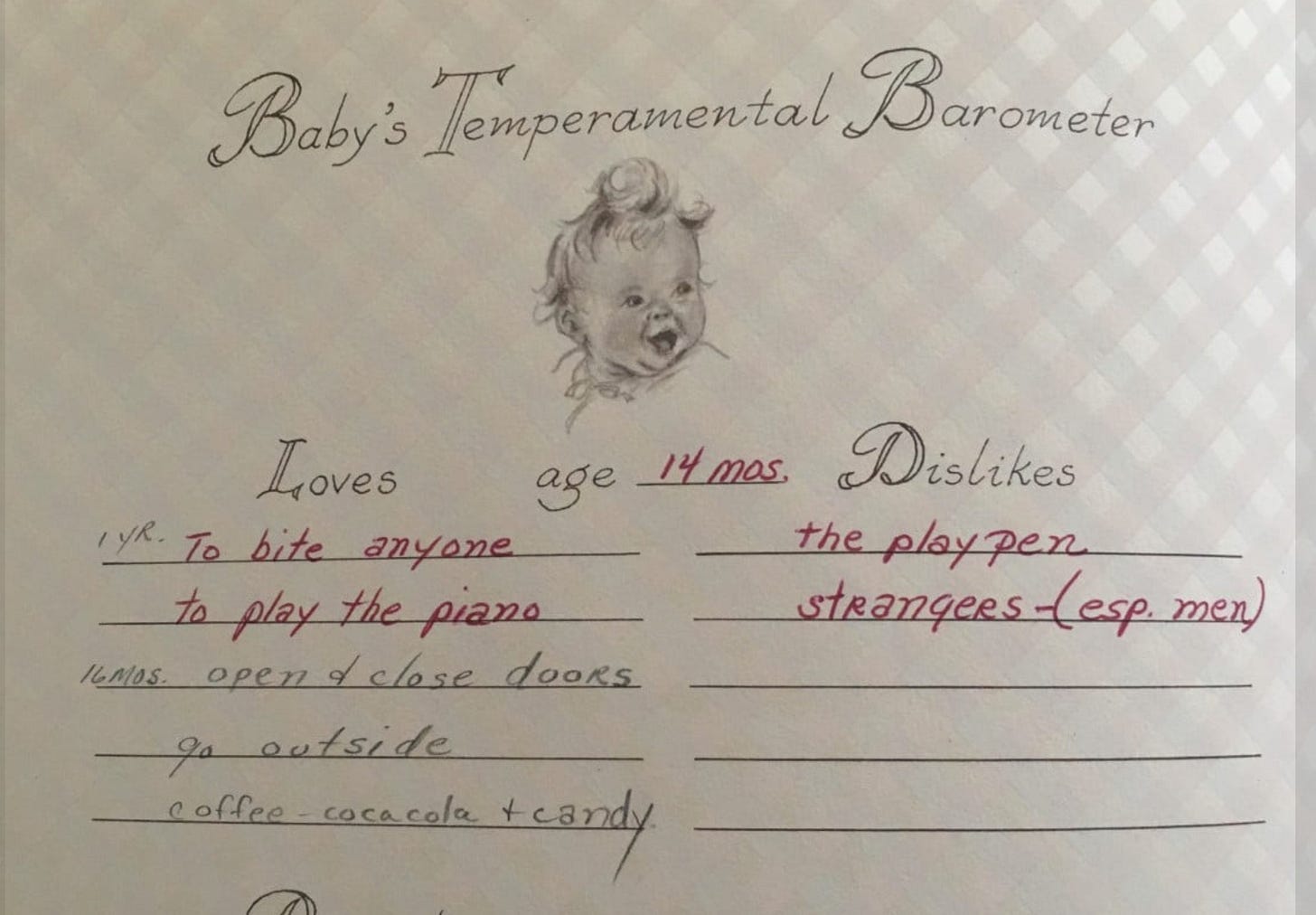

I must have had some musical inclination as a small child. My mother kept a ‘baby book’ of photos and observations. It’s unsettling to read her description of me at the age of one—when, she writes, I liked to play the piano and drink coffee.

That could still describe me today.

I’m probably still wary of strange men and continue to avoid sitting in a playpen. On a positive note, I don’t bite people anymore.

But I was not a child prodigy, not even close. Neither of my parents were musicians—so they didn’t see this as a career path.

I did have an Uncle Ted (I was named after him) who had an amazing musical gift, you might even describe it as genius. But he died in a plane crash at age 28, before I was born. So I never had him around as a role model, much to my later regret, although I may have benefited from a bit of his DNA.

But my parents did inherit his piano. That would later be very important in my development.

My first music lessons were a few encounters with Sister Camille Cecile, a nun who taught piano at my elementary school. These took place around 3rd or 4th grade, and I didn’t enjoy them. So I asked my parents if I could quit taking lessons, and they agreed.

They were spending three dollars per month on piano lessons. So if I wasn’t interested, that money could be used elsewhere in our tight family budget.

At that juncture, you would have never guessed that music would be important in my later vocation.

But something strange happened.

After I quit taking lessons, I continued to play the piano. In fact I started playing it more than ever—because now I was doing it for fun.

That’s how music should be pursued. For fun.

But there was a downside to this. I had no real direction, so I just invented my own way of learning about music. This involved composing my own simple songs. And I played other songs I liked, but did this mostly by ear. I was spending a lot of time at the piano, but it was very unstructured.

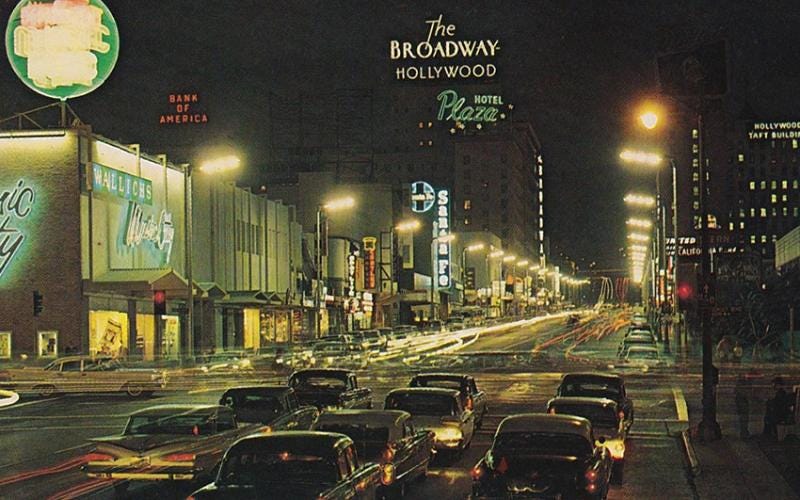

In my teen years, I spent a lot of my allowance money on sheet music. I often went down to Melody Music in my home town of Hawthorne, and occasionally to the Wallichs Music City branch in Torrance, across the street from the Del Amo Mall.

By the way, I suspect these were the same music stores frequented by Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, who grew up near my family home. They were the only places to buy music stuff nearby. If I wanted a larger selection, I had to convince a family member to drive me to the main Wallichs on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood—but that was a rare treat.

Wallichs in Hollywood was an amazing store. Movie stars (Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, etc.) were customers. Frank Zappa worked there selling hit singles to teens. Places like that simply don’t exist anymore.

I had some ability to read music, but I often just looked at the chord symbols above the music, and created my own arrangements of popular songs. You might say that was a sign of talent, but in some ways it was also a sign of laziness.

I mostly learned the songs I heard on the radio. On some occasions, I’d pull out a piece of classical music (or even ragtime, which started to enjoy a revival around that time), and play the written scores note-for-note. But I didn’t do anything in a consistent or disciplined way, even if I was getting better at the piano.

That’s when I discovered jazz.

But here’s the crazy thing. I learned about jazz at the public library. That is so uncool, I’m almost ashamed to admit it. I stumbled upon a stack of Downbeat magazines at the Hawthorne library, and read through them like they were some kind of holy script. Then I found some jazz books there too, and read every one of them.

At this juncture, I had never actually seen a jazz band make music. I didn’t even own any jazz records. How bizarre is that? I was turning into a jazz fan by reading about the music.

Then one day I decided to visit a jazz club.

This sounds like an easy thing to do, but it wasn’t at all. For a start, none of my friends went to jazz clubs, and it took me a while to find where these venues were located. Even worse, the clubs often refused entrance to teenagers. For that reason, I had to rule out going to Concerts by the Sea in nearby Redondo Beach—Howard Rumsey had a strict ‘no teens’ rule. Jazz greats played there regularly, and I later heard them by hanging around outside the door—but I never once went inside, or even saw the inside of the club.

Then one day I heard an advertisement on the radio for the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach. The announcer would reel off the names of musicians playing there, and always conclude the ad by saying: “Minors are always cool at the Lighthouse.”

That meant me. I was a minor. And I wanted to be cool at the Lighthouse.

The club was located about 7 miles from our family home in Hawthorne. That’s not much in SoCal terms. Not only was the Lighthouse much closer than any of the ritzy Hollywood clubs, it was also cheaper.

This would be my gateway drug.

I chose an artist at random. I had seen the name Yusef Lateef in Downbeat magazine, but I may not even have known what instrument he played. But if he got written up in a national magazine, that was enough for me.

So I showed up at the Lighthouse one night, not knowing much. But I was fortunate—the band was hot. Saxophonist Lateef had brought his working group of the time, which featured pianist Kenny Barron, bassist Bob Cunningham, and drummer Al ‘Tootie’ Heath.

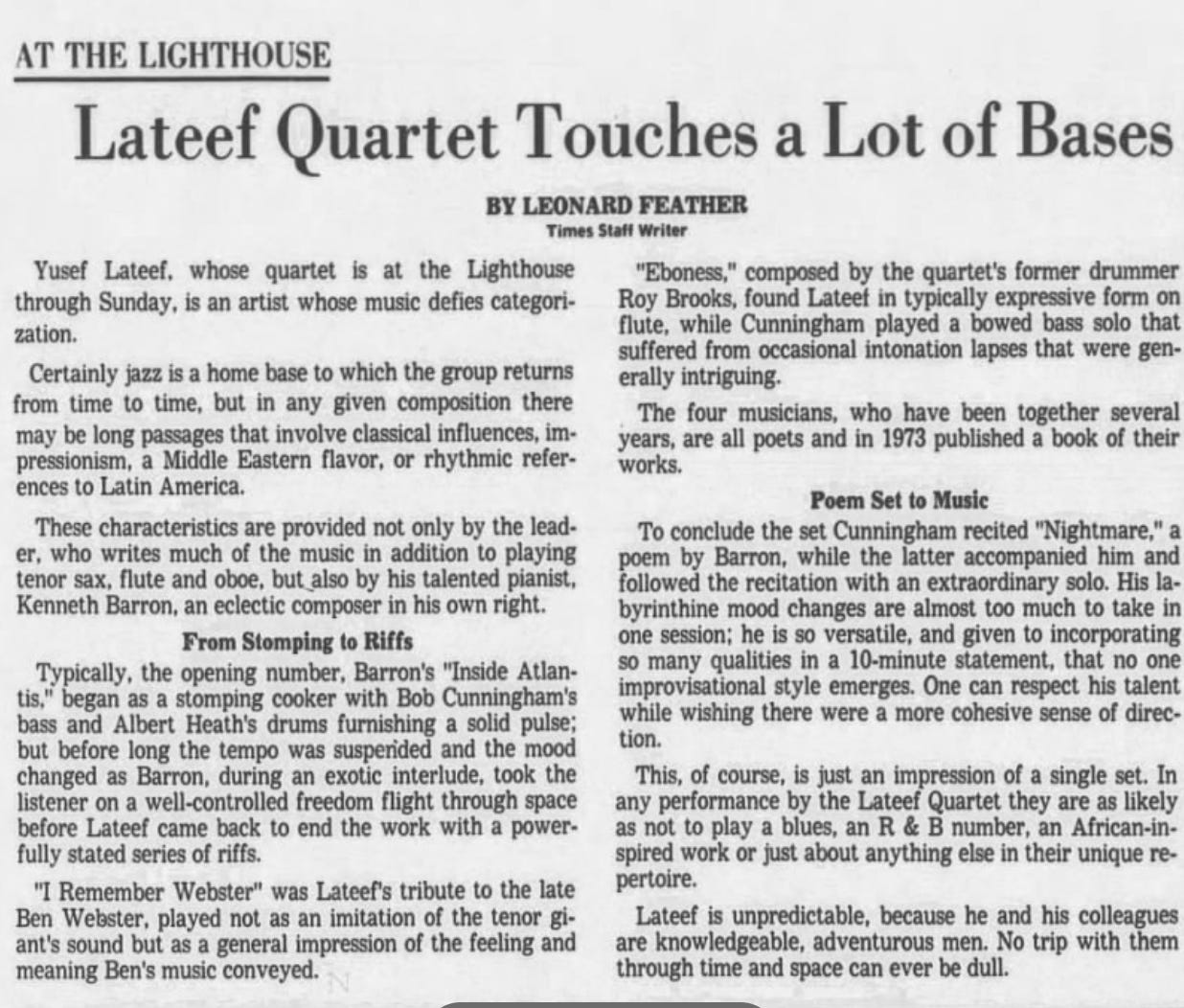

There were also ‘jazz celebrities’ in the audience. Leonard Feather, the influential jazz critic for the LA Times, was sitting a few feet away from me. Pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi was sitting next to him. (I wouldn’t have recognized them, except that Lateef acknowledged their presence from the bandstand.)

I later realized that musicians often play better when visitors of this sort are in attendance. So this was another lucky break for my virgin jazz club experience.

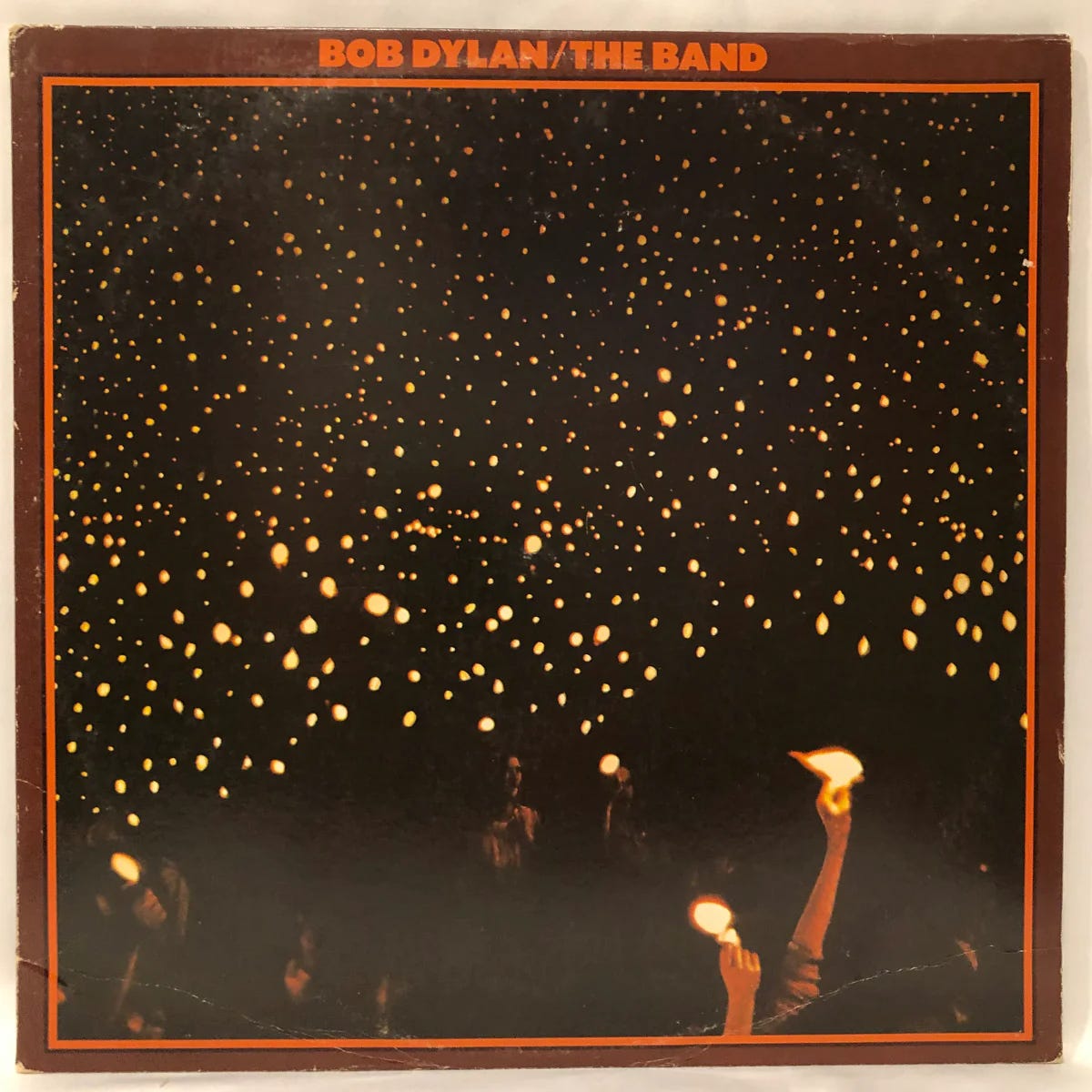

When the musicians stepped on to the bandstand, the first thing I noticed was how close I was to them. A short while before, I had seen Bob Dylan play with The Band at the Forum in Inglewood, and could barely pick out the musicians from my seats high in the nosebleed zone. But these jazz clubs were different, very different—I was just a few feet away from the action, and every gesture, gaze and interaction among the players was discernible.

I later learned how important these small gestures are in improvisation. I’ve seen bandleaders change the entire course of a song with just a single look. I didn’t know any of that back then, but I understood immediately that experiencing the music at such close quarters was what I had always craved without even knowing it.

But then the music started, and my life changed in the next few seconds.

Lateef counted in a very fast tempo. Up until this time, I had focused mostly on rock, pop, and classical music—and had no experience with songs played at this breakneck pace. Just hearing the rhythm section lock together at this tempo was exhilarating.

The impact on me was almost instantaneous.

Years later, I met an anthropologist who had studied kabuki theater in Japan. He told me that members of the audience often shouted out exhortations during a performance. He said he had been in attendance at one event where the guy behind him jumped up from his seat, at an especially dramatic juncture, and exclaimed:

This is the moment I’ve been waiting for.

When I heard him tell that story, I immediately recalled my initiation into jazz at the Lighthouse. That was exactly what I felt around 17 seconds into the performance by the Yusef Lateef Quartet. I honestly wanted to jump up, and tell everybody in the nightclub:

This is the moment I’ve been waiting for.

I knew in that instant that everything in my life had been leading up to this. And I’d been wasting my time with rock and pop and classical music. My destiny was jazz.

I should have figured it out before. This music had everything I’d ever wanted in a creative experience: intensity, intelligence, spontaneity, sophistication, interaction, emotional integrity, analytical depths.

But if this realization only took a few seconds, the song itself lasted for around 30 minutes. I had never heard a song that long before.

I was absolutely convinced the band must be playing a medley. That was my only previous conception of such an extended performance. The fact that the group went through several tempo changes, and even let Kenny Barron play a solo piano interlude, added to my sense of dislocation.

After this song finally came to a conclusion, Lateef stepped up to the mic and said that they had just played a composition called “Inside Atlantis” by Kenny Barron.

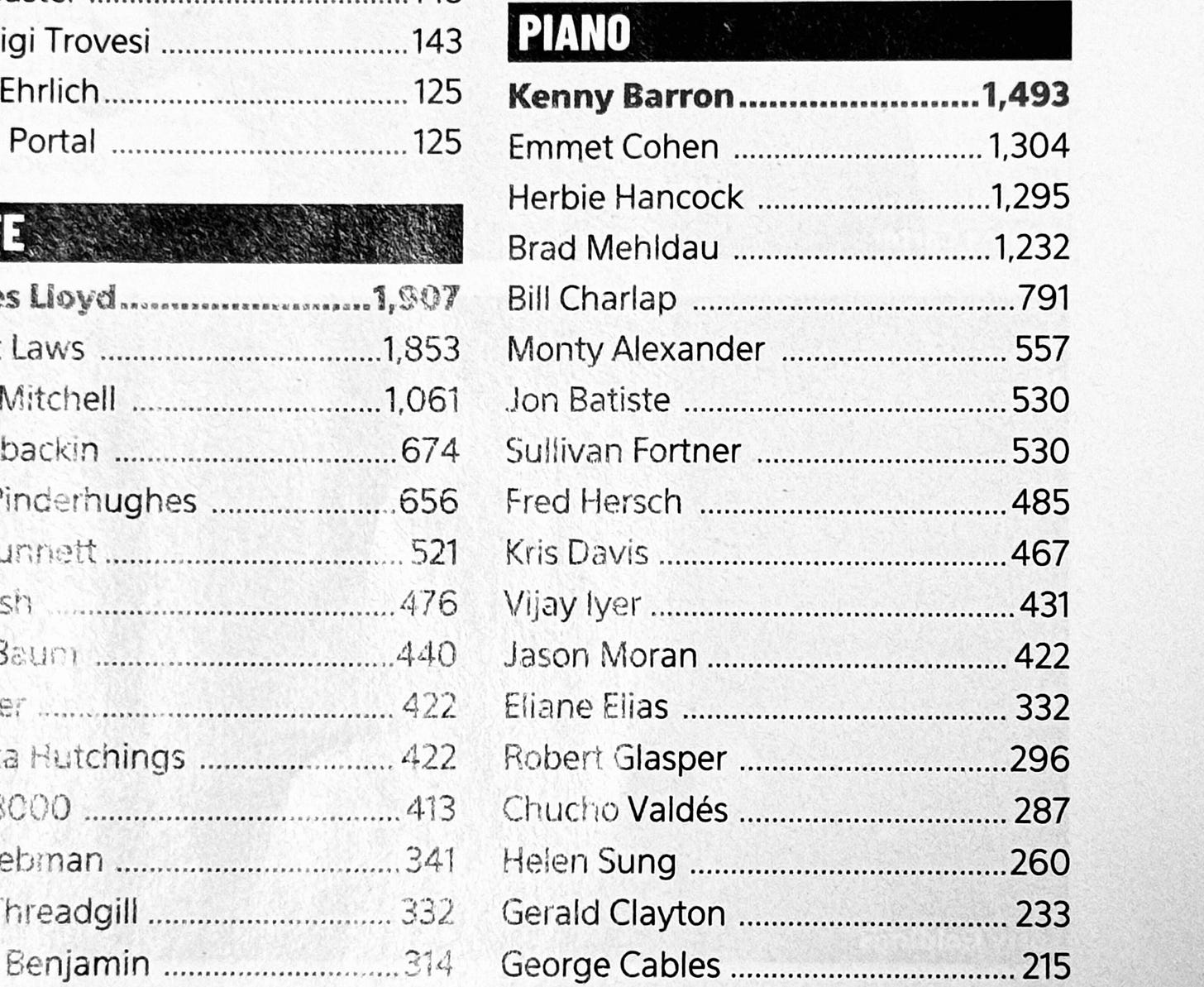

Nowadays, Kenny Barron is a jazz legend. He recently took the stop spot in the Downbeat poll—beating out all other jazz pianists. But he was less known in those days, and I had never heard his name before that evening.

This was, after all, my first visit to a jazz club, so I simply assumed this was what a typical jazz pianist did on a typical evening—and this both delighted me and shook me up a bit. There was clearly a whole world of musical creativity that had been thriving in the jazz world, but I had never been aware of it until that night.

In subsequent months, I ransacked every record store in LA, trying to find this song “Inside Atlantis” on an album. I wanted to study it and unlock its secrets.

I had no luck. It had never been recorded. (It didn’t show up on an official album release until 2024!)

That also taught me something important about jazz. It happens in the moment. And if you hear it one night, don’t expect to find it on an a record. You can even go back and hear the same band the next night, and have a completely different experience.

Many decades later, I found a YouTube video of that Lateef band playing “Inside Atlantis.” This video eventually got removed from the web, but a shorter version of the song—which, unfortunately omits Kenny Barron’s solo interlude—is now available. So you can judge for yourself how a teen raised on top forty radio would have been totally unprepared for something of this sort.

I stayed for all three sets that night. I left the Lighthouse some time after 1 AM as a totally changed changed person.

Let me assure you: You won’t have this kind of experience staring into your phone. Nope. Never.

More than fifty years later, I still remember everything vividly. That’s how momentous this event was for me.

I can even tell you that bassist Bob Cunningham was wearing a Hunter College sweatshirt when he stepped on the bandstand. In subsequent days, I had a strong desire to own a Hunter College sweatshirt of my own.

I recently uncovered a review of the performance. For me it was life-changing. But for LA Times critic Leonard Feather it was just another gig.

Here’s the aftermath.

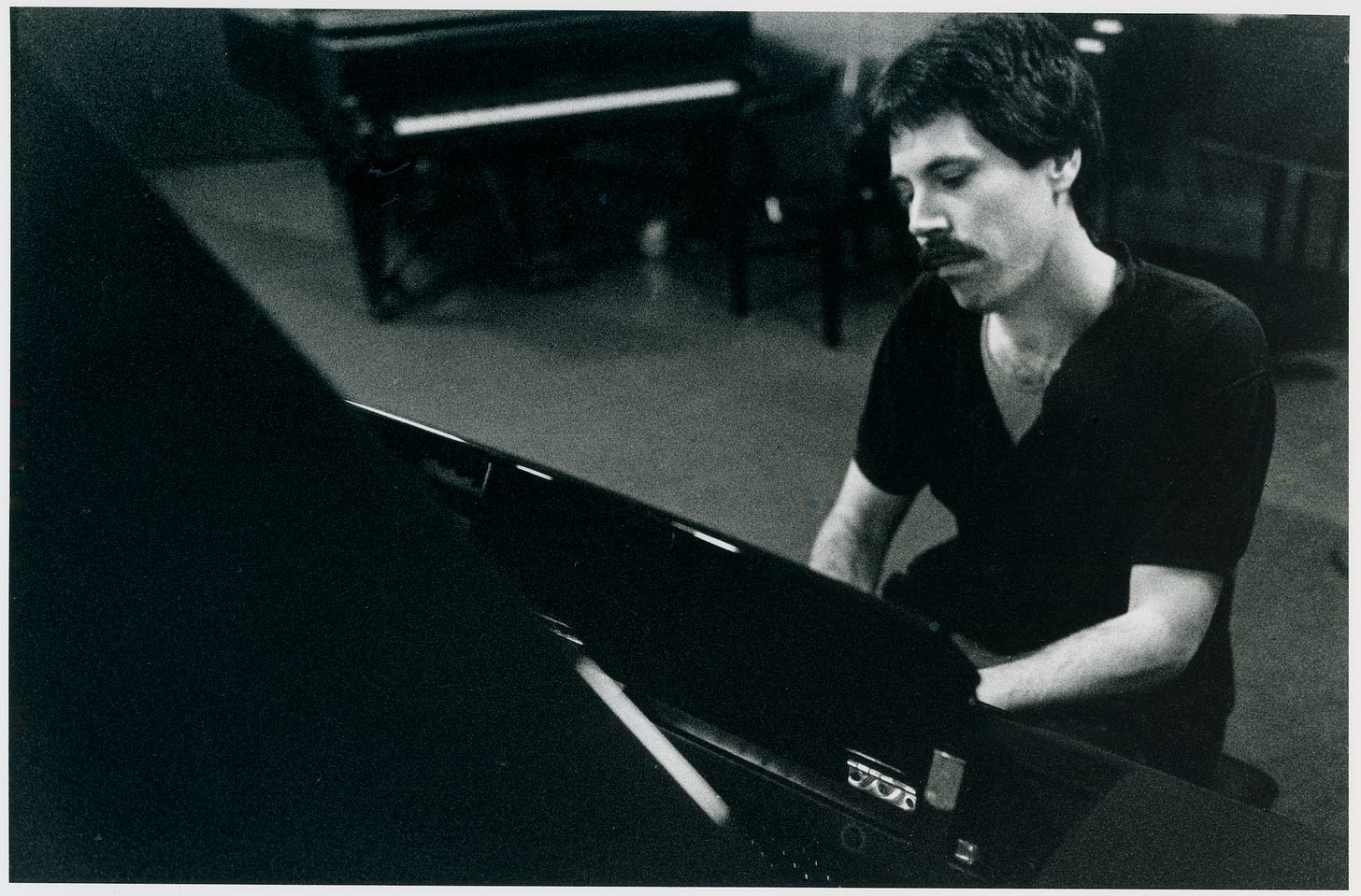

When I heard the music that night, I realized how much I still needed to learn. Although I had been playing piano for years at that point, I couldn’t understand much of what Kenny Barron was doing at the instrument.

In addition to these conceptual limitations, I also had technical constraints. I knew I needed to devote a lot more time to the keyboard—improving my control, tone, and dexterity. My fingers needed to be stronger, more independent. My mind, too.

I now started spending three hours per day, on average, at the piano. On some occasions, I would spend as much as six hours per day at my music.

It was my love, my passion, my everything.

TWO YEARS LATER: I could play jazz well enough to get gigs and start making a reputation as a professional musician.

FIVE YEARS LATER: I could play with top notch jazz professionals and hold my own, and maybe even shine for a moment

TEN YEARS LATER: I could walk into the recording studio, and play this—the first track on my first album.

My performing career came to an early end—because of a physical ailment. But I have no regrets. None.

Perhaps there were other lives I could have lived. But this was the one destiny gave me. Even today, I’m still living out the consequences of that Lighthouse moment, even if it doesn’t mean acclaim on the bandstand.

You don’t choose these things. They choose you. That’s how true vocations happen. The only difference in my case is that it all happened in just a few seconds.

Lovely article!

I went to clubs in NY, SF and NY till I started my own record label and managed Jazz, Hip Hop and Rock Artists. Great article