The Jazz Origins of James Bond

Almost every element in James Bond's personality reflects a jazz sensibility—and that was by design

A few minutes into the new film No Time to Die, Daniel Craig’s final outing as James Bond, our gallant superspy flirtatiously comments to actress Léa Seydoux: “We have all the time in the world.” That may seem like just one more come-on line in a movie franchise built on pick-ups and hook-ups, but seasoned jazz fans recognize something more in the phrase.

Back in 1969, Louis Armstrong’s rendition of “We Have All the Time in the World” was featured as part of a romantic interlude in the James Bond film “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.”

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The context was much more than a one-night stand, but rather the extraordinary moment when James Bond courted his wife, the Contessa Teresa di Vicenzo (aka Tracy Bond)—soon killed by a Bond villain’s bullet. Her tombstone even reads: “We Have All the Time in the World.”

So Louis Armstrong helped bring agent 007 a short taste of marital bliss, you might say. But the jazz connections of James Bond run much deeper than that.

Ian Fleming, who introduced the Bond character in his novel Casino Royale, back in 1953, was a devoted jazz fan. His tastes were a bit old-fashioned, but he was hardly the only British writer to prefer traditional jazz even in the face of bebop and other modernist movements. Philip Larkin, as esteemed as any British poet of that era, even took a side job as a jazz record reviewer, where he fought valiantly for the honor of the old New Orleans and Chicago players. Novelist Kingsley Amis, Larkin’s friend and fellow jazz connoisseur, revered Sidney Bechet, Pee Wee Russell and Henry ‘Red’ Allen, preferring them over more up-to-date exponents of the idiom. Eric Hobsbawm, the influential British scholar, also wrote about jazz, but under the pseudonym Francis Newton, and again favored the older sounds, which he viewed as a kind of vernacular soundtrack for his populist concerns as a Marxist historian.

Fleming’s jazz tastes were hardly so sophisticated. When he appeared on the BBC show Desert Island Discs in 1963, he said that his favorite song was “The Darktown Strutters Ball” by Joe Fingers Carr, a rough-and-rowdy example of honky-tonk jazz. (By comparison, his favorite book was War and Peace by Tolstoy—what a contrast!) This is a step below Armstrong, maybe several steps, but it revealed a taste for brash sounds and lively syncopation.

“He learned all this from Chicago jazz. Like Bond, it’s passionate without falling into mere sentimentality, heartfelt but never losing its ironic or humorous touches, capable of elegance but never allowing you to forget the intensity lurking just below the surface.”

It’s clear that Fleming had music in mind when he created James Bond. In two different Bond books, Fleming notes that his secret agent looks like jazzy songwriter Hoagy Carmichael. In Casino Royale (1953), a character describes Bond in these words: “He is very good-looking. He reminds me rather of Hoagy Carmichael, but there is something cold and ruthless in his. . .” The sentence is never finished, but you get the idea. In Moonraker (1954), Fleming further emphasizes the resemblance, when fellow agent Gala Brand remarks: “Rather like Hoagy Carmichael in a way. That black hair falling down over the right eyebrow. Much the same bones. But there was something a bit cruel in the mouth, and the eyes were cold.”

Hoagy Carmichael must seem an unlikely role model for a superspy. He came of age playing ragtime and jazz piano in the Midwest, and eventually fell under the influence of the great Chicago players of the era, especially Bix Beiderbecke. But Carmichael would achieve even more success as a songwriter, and composed some of the most popular hits of the 20th century, including “Star Dust,” ‘Georgia on My Mind,” “The Nearness of You,” “Skylark,” and “Heart and Soul.”

In this clip, from the 1944 film To Have and Have Not, he even gets the attention of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

What does this have to do with espionage? I suspect that Fleming was especially attracted to the paradoxical nature of Carmichael’s demeanor, which seemed both rugged and romantic—with each of those two qualities reining in the other. He learned all this from Chicago jazz, where so many of the key elements we associate with this music also describe agent 007. Like James Bond, that music is tough-minded and spontaneous, passionate without falling into mere sentimentality, heartfelt but never losing its ironic or humorous touches, capable of elegance but never allowing you to forget the intensity lurking just below the surface.

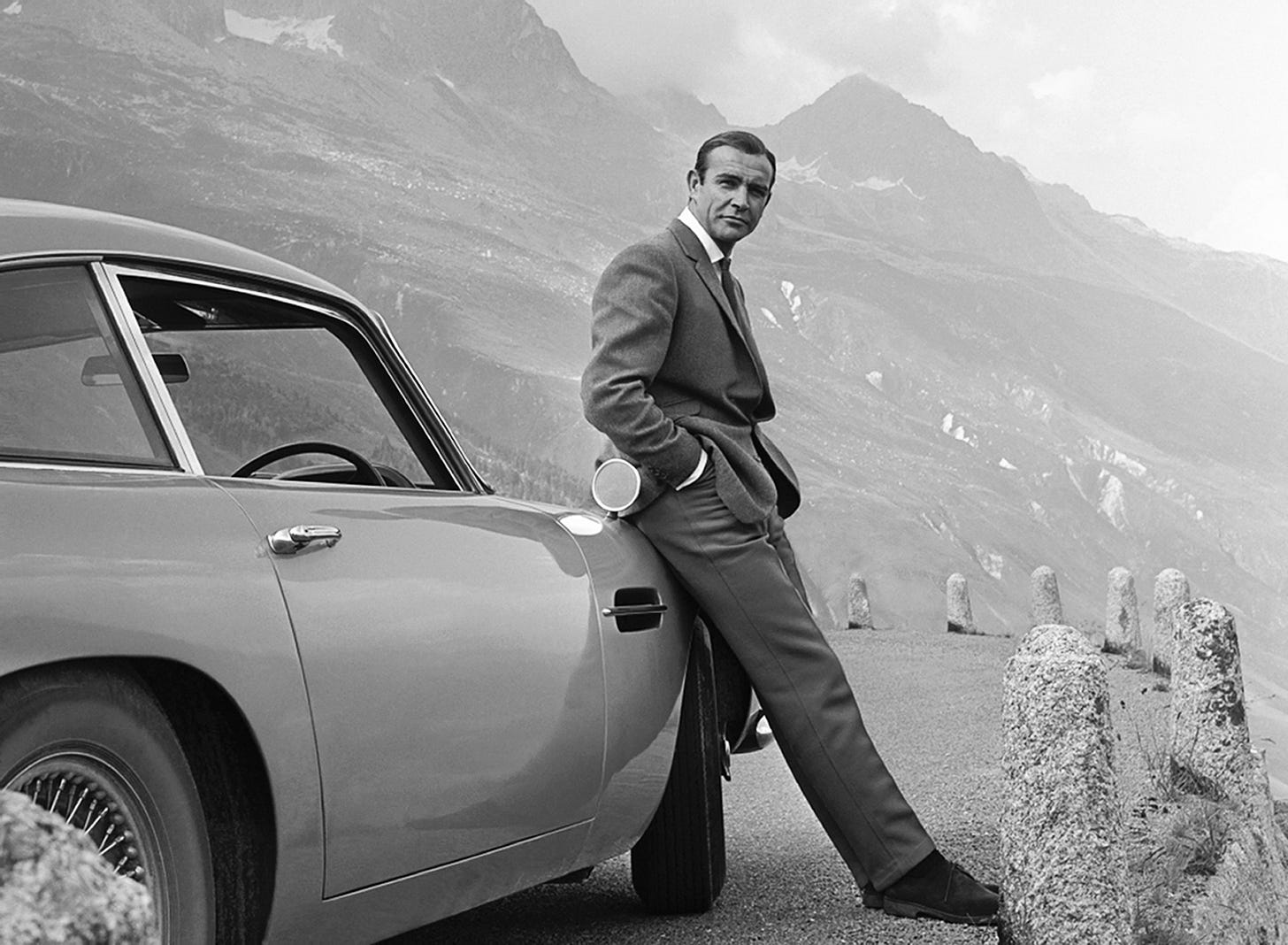

Fleming’s books don’t tell us much about James Bond’s musical tastes, but there are hints in the movies. There’s a brief interlude in The Living Daylights where Bond listens to jazz in his Aston Martin—but it’s interrupted because he needs to use the car radio to check out the police shortwave band.

In Goldfinger, we learn that James Bond is not a fan of the Beatles—a group that should only be heard, he claims, while wearing earmuffs.

Yet James Bond’s most sophisticated jazz moment comes in the novel For Special Services by John Gardner, who continued the franchise after Fleming’s death (following a strange interlude when Kingsley Amis authored a Bond book). Here the secret agent is depicted listening to the great jazz piano virtuoso Art Tatum, specifically the song “Aunt Hagar’s Blues.” This is endearing, if somewhat strange—because Gardner had claimed he wanted to update 007 for the 1980s. So why not Madonna or Michael Jackson? But instead, Bond is grooving to sounds from the 1940s.

Yet this is fitting, and as it should be. James Bond just seems jazzy. I can’t imagine him digging punk or disco or hip-hop or heavy metal—although I can easily imagine Bond villains enlisting those various soundtracks. When he isn’t onscreen and on-duty, I imagine him picking out something better suited to accompany the shaking of martinis or cleaning of his Beretta 418 and Walther PPK.

That has to be jazz, and suitably aged, perhaps from the 1950s. Maybe Frank Sinatra on Capitol Records, or Miles Davis’s tracks with Gil Evans, or possibly the Modern Jazz Quartet (who had similar tastes to him in clothes). And even as the Bond persona continues to evolve and adapt to passing tastes, that jazzy element—present at 007’s origin, so to speak—can never completely disappear. It’s embedded in the character’s DNA, and is thus destined to persist, even after all the time in the world.

Perhaps the most interesting example of Bond listening to jazz-ish music comes in Diamonds Are Forever (the book), where he enters Tiffany Case’s apartment and finds her listening to “Feuilles Mortes” (“Autumn Leaves”), a track from an album by the Hungarian classical-turned-pop pianist George Feyer (1908-2001). He likes it so much that while she’s getting dressed he takes down the label and number: Vox 500.

I love this, Ted! Of course a cool cat like Bond would prefer the sophisticated stylings of the Chicago jazz scene. Now I want to go back and LISTEN to the Bond films.