The Importance of Counter-Clockwise Dance Rituals

The pathway to magical living goes in a circle

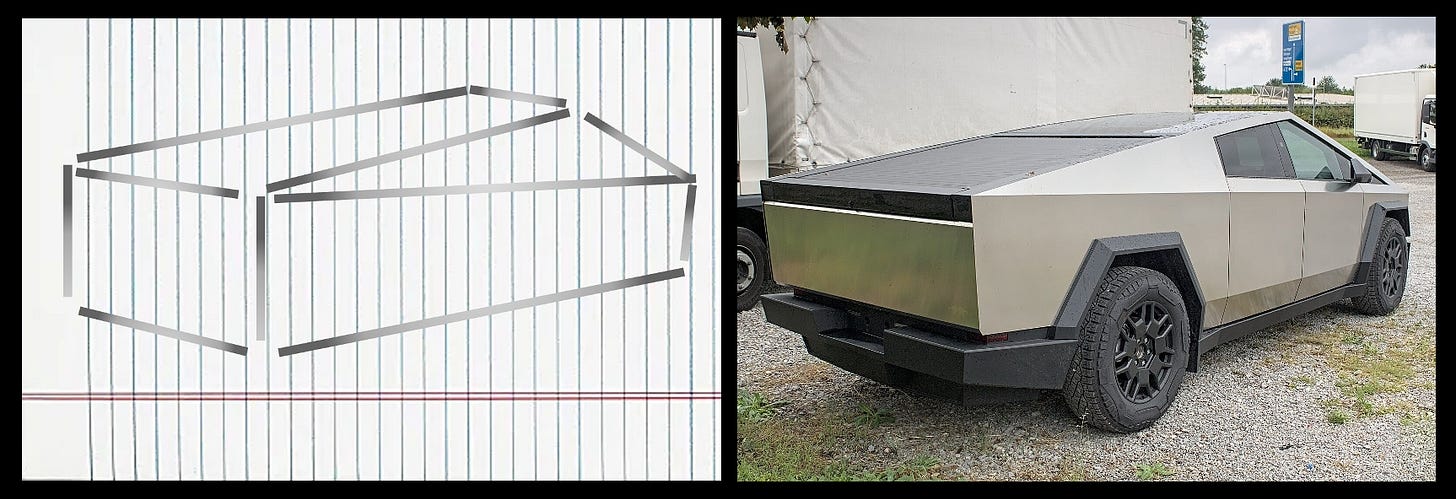

We live in a world of lines, squares, and boxes. Here’s what a modern city looks like.

Most of us live inside a grid—and it’s usually part of a larger grid. In this kind of world, life is mostly moving from one rectangle to another.

We navigate through these rectangles by holding other rectangles in our hands.

Only in rare moments do we get a glimpse of life outside these grids. Many find this disorienting or frightening. They can’t wait to return to the safety of the rectangle.

The rectangle is all about solidity, strength, and separation. That’s why the iPhone, like the skyscraper, evokes the defensive boxes of medieval fortresses—the safest rectangles of their time.

Neuroscientist and philosopher Iain McGilchrist—whom I’ve claimed elsewhere “ranks among our half dozen most important living thinkers”—explains that “straight lines predominate wherever the left hemisphere [of the brain] predominates.”

The pervasiveness of straight lines and box-centric lifestyles in today’s culture is a warning sign that we are fostering a psychically claustrophobic society—one that obsesses over STEM rationality, prefers numbers over emotions, fears lived reality, and cuts itself off from holistic thinking.

There are no straight lines in nature, McGilchrist points out, except for the horizon—and even that is an illusion. The horizon is actually curved, like Earth itself.

If you value articles like this, please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

The circle is always the symbol of wholeness, of health, of connection. Even the word centeredness conjures up mental images of a circle. To live a centered life is the opposite of hiding inside the fortress.

Confronted with a circle, you cannot analyze beginnings and ends—you can’t even find them. In the circle opposites not only coexist, they actually join hands and come together.

This concept of the cooperation of opposites has almost completely disappeared from Western society today. But you see it in other settings—for example in Taoism, where it is symbolized in the yin-and-yang.

Here we grasp that our opposite—our nemesis or rival—helps to define us, and even gives us power. We do the same in return.

There are only a few Western thinkers who have given much credence to this. Hegel is a prominent example, with this concept of the dialectic. For the most part, we need to move from Western to Eastern traditions to nurture this openness.

When I recommended Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching—the core Taoist text—for my 52-week humanities immersion project, I got some pushback from readers. One complained that the work is “meaningless”—filled with contradictory and opposed views.

I don’t disagree with this. But that’s precisely why I value this work. I replied:

The purpose of that book is to force people out of their linear, rationalistic, and algorithmic ways of thinking. The paradoxes in the text are necessary to serve that purpose. There’s great value in learning how to reconcile opposites, and this is the book to do it.

That attitude impacts my approach to music, and other creative fields.

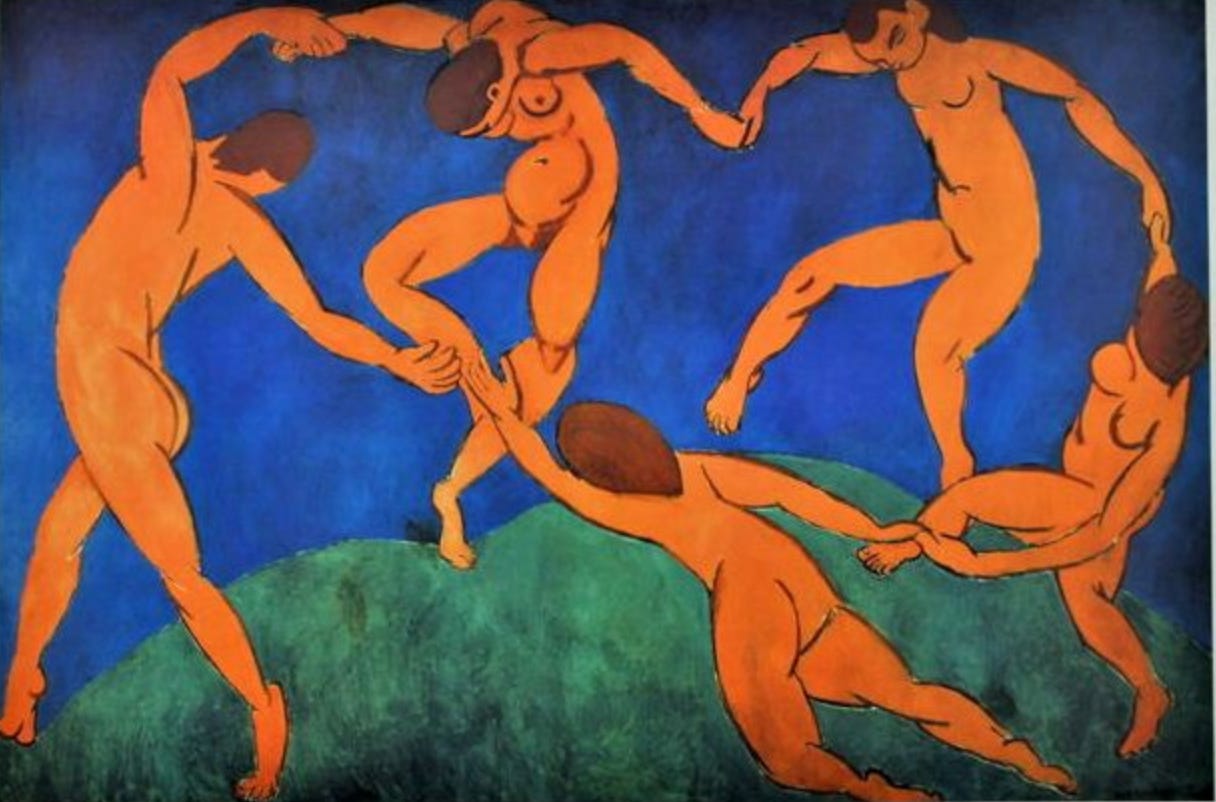

The ring dance is an embodied way of reaching the same openness to opposites. It unifies and merges—both visually and psychically.

Shakespeare’s plays often ended with circle dances, and he associates it with magic. Fairies dance in a circle in A Midsummer Night's Dream. Witches do the same in Macbeth.

And it’s not just Shakespeare. Magical circle dances are frequently depicted in Renaissance paintings.

You don’t see many circle dances nowadays—they violate the linear motion of everything in our left-brain dominated analytical world. But the circle dance is the most important ritual in many cultures.

And the most vital circle dances move in a counter-clockwise direction. When this happens, the participants are typically guided by their left eye and left foot, which tap into the right hemisphere of the brain.

Emotional togetherness and a sense of belonging to a whole are stirred up by this kind of motion. But it defies almost everything we are taught in Western society.

In African American culture, this counter-clockwise circle dance is called the Ring Shout—and I can’t over-emphasize its importance. Researchers have found it everywhere in these traditional societies.

The Ring Shout originates in Africa, where counter-clockwise circular dancing has long been a defining part of key rituals. You might say that this is the quintessential symbol of social solidarity in Africa.

Here’s an illustration from David Livingstone’s 1857 account of his travels in South Africa.

I take this dance so seriously that it is the very first topic I address in my book The History of Jazz. Here’s part of what I say there.

Scattered firsthand accounts provide us with tantalizing details of the slave dances that took place in the open area [of New Orleans] then known as Congo Square—today Louis Armstrong Park stands on roughly the same ground—and there are perhaps no more intriguing documents in the history of African American music. Benjamin Latrobe, the noted architect, witnessed one of these collective dances on February 21, 1819, and not only left us a vivid written account of the event but made several sketches of the instruments used. These drawings confirm that the musicians of Congo Square, circa 1819, were playing percussion and stringed instruments virtually identical to those characteristic of indigenous African music….

These gatherings, a mixture of the ceremonial and social, further broke down barriers between secular and spiritual impulses—a firsthand account from 1808 even uses the word worship to describe them.

The dances themselves, marked by clusters of individuals moving in a circular pattern—the largest less than ten feet in diameter—harken back to one of the most pervasive ritual ceremonies of Africa. This rotating, counterclockwise movement has been noted by ethnographers under many guises in various parts of the continent. In the Americas, the dance became known as the ring shout, a ritual that, in the words of scholar Sterling Stuckey, served as “the main context in which Africans recognized values common to them.” The appearance of this African carryover in New Orleans is only one of many documented instances in the New World. This tradition persisted well into the twentieth century: John and Alan Lomax recorded a ring shout in Louisiana for the Library of Congress in 1934 and attended others in Texas, Georgia, and the Bahamas. As late as the 1950s, jazz scholar Marshall Stearns witnessed unmistakable examples of the ring shout in South Carolina…..

Even after the public gatherings came to halt, the tradition of the ring shout lived on in many ways. Samuel Floyd has gone so far as to contend that the ring later “straightened itself to become the Second Line of jazz funerals.” Here, he writes, “the movements of the participants were identical to those of the participants in the ring—even to the point of individual counterclockwise movements by Second Line participants.” Only the ring itself was missing, since the participants had a set destination, and needed to direct their movements back to town from the cemetery.

In other words, American values demanded that the ring become a straight line—with a destination, instead of a self-reinforcing circular flow.

Western culture once embraced similar counter-clockwise dances. You see them, for example, in this 1616 painting of a peasant dance by Pieter Brueghel the Younger.

In contrast, group dances at weddings today are typically linear, not circular.

They’re sometimes even called line dances, to clear up any misconception.

This makes no sense. The dance floor is not constructed to accommodate linear motion. A circular dance is a better use of the available space. But our mindset today resists curves, and fixates on lines.

Yet people still crave the circular. That’s why they participate in the wave at sporting stadiums. And it’s why the most popular stadiums, going back to the Roman Colosseum, are curved (even when the playing field is a rectangle). Or just look at the circular parks and town centers that still survive in some cities—people instinctively congregate in those places, in search of their lost wholeness.

We ought to remember what Antoni Gaudí told us: “The straight line belongs to men, the curved one to God.” In sad proof of that aphorism, Gaudí stirred up intense controversy when he tried to bring those curves into modern architecture. But the public understood, at some instinctive level, the power and allure of his organic shapes.

For an especially glaring example of linear tyranny, see the ugly Tesla Cybertruck—which looks like it was designed by a bored eight-year-old with a ruler.

That’s the closest thing to a coffin you can find on wheels. And that’s hardly a coincidence—the curve is organic and living, while the line is cold and deadening.

Am I make an extreme generalizations here? It sounds like I’m saying that…

Culture that reduces everything to lines and boxes tends to be emotionally stifled, disconnected from community, and cut off from holistic thinking.

Culture that embraces the circular and the curved (especially in counter-clockwise movement) is healthier, more centered and whole, more likely to build connections with others.

Yes, I am saying that—although I recognize exceptions and limits of generalizations.

But celebrating the circle does not mean renouncing the line. One of the lessons of the roundness—and its related concepts of yin-and-yang, and the dialectic, and the Gothic curlicue—is that I can have both one thing and its opposite.

So we don’t need to choose. Even in our cities of boxes and grids, we can build our own circles. And what a lovely way of living that might be.

"That’s the closest thing to a coffin you can find on wheels."

Amazing . That is exactly what it is like. I will forever see one as that now ...

We circle-danced at our wedding. Love a good circle. And yet... this also reminds me of a contrarian Chesterton quote:

“As we have taken the circle as a symbol of reason and madness, we may very well take the cross as a symbol at once of mystery and health. Buddhism is centripetal, but Christianity is centrifugal: it breaks out. For the circle is perfect and infinite in its nature; but it is fixed for ever in its size; it can never be larger or smaller. But the cross, though it has at its head a collision and a contradiction, can extend its four arms for ever without altering its shape. Because is has a paradox in its center it can grow without changing. The circle returns upon itself and is bound. The cross opens its arms to the four winds; it is a signpost for free travelers.”