The Hit Singles of Sun Ra

On the 30th anniversary of the Afrofuturist's death, I explore the oddest discs in his discography

Nobody in American music had a more amazing life than Sun Ra. He started out as a poor kid in Birmingham, Alabama named Herman Blount, and turned himself into the musical guardian of the galaxy.

America is all about reinventing yourself. That’s up there with life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. But not even the Great Gatsby could reinvent himself like Sun Ra.

But what happened after Sun Ra’s death, exactly 30 years ago today, is even more amazing. I’ve never seen any jazz musician gain more posthumously in reputation and influence.

During his lifetime, many jazz fans didn’t know quite what to make of this iconoclastic performer—who dressed in peculiar costumes, played even more peculiar music, and claimed that he came from the planet Saturn. Much of the jazz audience dismissed all this as a tired gimmick—like Kiss’s silly clown makeup or those goofy animal outfits on The Masked Singer.

But nobody’s laughing now.

Nowadays Sun Ra is celebrated as a pioneer of the Afrofuturist movement.

But that hardly makes it easier to come to grips with this wide-ranging and rule-breaking artist. People think they understand Sun Ra because they’ve attached him to a movement. But Sun Ra is still a strange musician.

And he will always be a strange musician. That’s half the fun of listening to his records. Even if they actually find music on Saturn someday, it will hardly be as surprising as his delirious discography.

Today I want to focus on one of the oddest aspects of his legacy—namely his catalog of hit singles.

I use the word hit loosely. Very loosely.

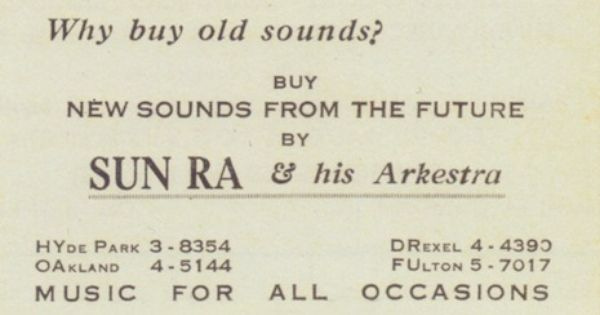

Other musicians released 45 rpm singles because they believed their songs had potential for radio airplay and jukebox spins. But did Sun Ra really aim at the charts? Maybe the astrology charts, but not the kind they publish in Billboard.

My theory is that Sun Ra liked the number 45 because the planet Saturn rotates completely in 10 hours 45 minutes and 45 seconds. But who knows? In any event, his 45s were hits only in the sense that the music sort of hits you over the head.

And still does, 30 years after he left the planet.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

THE HIT SINGLES OF SUN RA

By Ted Gioia

If you happened to purchase Sun Ra’s debut 45 single back in the early 1950s, you got something quite strange.

That was actually the name of the song—“I Am Strange.”

The song opens with dissonant piano chords of uncertain tonality. And then Sun Ra begins to whisper:

I am strange.

My mind is tinted with the colors of madness.

They fight in silent furor in their effort to possess each other.

I am stra-aa-aa-nge!

You might think this is just the intro, and the song proper will soon begin. But no dice. This whispery monologue is the song. So you flip the record over, and listen to the other side. And it’s even stranger than “I Am Strange.”

Here Sun Ra puts away the piano, and now recites to the accompaniment of the ‘space harp’. This track is called “I Am an Instrument.” But what it really sounds like is an experimental poem. Or maybe a sermon for a new religion. Or just a description of a really bad dream.

The one thing it doesn’t sound like is a hit single.

The Honest Broker is a reader supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

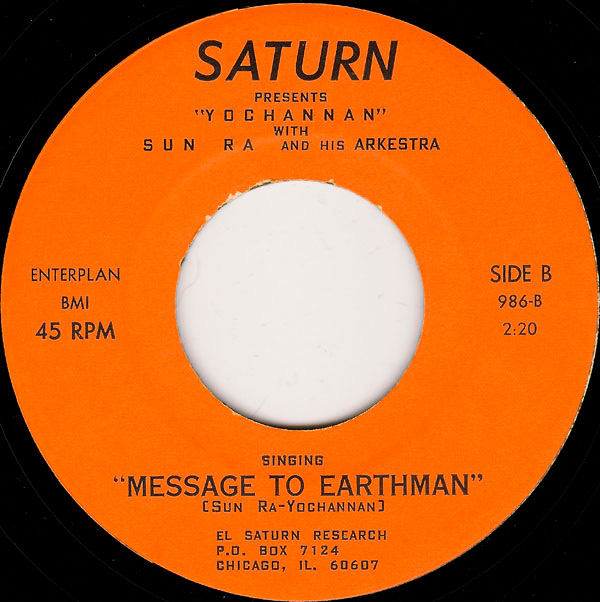

Perhaps some younger readers are unfamiliar with 45 rpm records. But here’s a quick summary: They were tiny records that were supposed to grow into big hits.

This new recording format—also known as the single—was launched by RCA in 1949. The singles were cheap and convenient, but they had one disadvantage. You could only fit one song on each side of the record. So you didn’t put out a single unless you had a winning song that deserved to be showcased.

Around the same time, Columbia introduced the long playing album (LP). The music industry quickly adopted both formats. Standard practice for the next four decades would be to release new music on LPs that typically had 10-12 songs, and then pick the most likely radio hit for promotion as a single.

Clearly Sun Ra didn’t see things that way. He used 45s the way Dr. Frankenstein used cadavers and abnormal brains—for experiments!

So he picked tracks for 45 single release that had zero potential for radio airplay. None of them ever became hits—or even came close.

But like the man said: He was stra-aa-ange!

Sun Ra is celebrated today as a jazz visionary and an originator of Afrofuturism. Conferences are held to assess his aesthetic theories and disruptive practices. He is hotter now than at any time during his life, and for good reason. Sun Ra launched a movement that is trendier than ever.

But I never heard anybody describe Sun Ra as an Afrofuturist back in the day. By the conventional standards of the 1950s entertainment industry, he was just a man with a gimmick. He pretended that he came from outer space, and dressed the part. In fact, the whole band shared his tastes for intergalactic costumes.

Hey, maybe he invented cosplay too. Can we hold a conference about that?

The music business knew all about people with gimmicks. They were called novelty acts. This was an easy pigeonhole for placing Sun Ra.

There was just one problem. Sun Ra stayed in character all the time. He didn’t go home, take off his space suit, open a beer and act like everybody else. His house at 5626 Morton Street in Philadelphia, where he lived for 25 years, became known as The Arkestral Institute of Sun Ra. This wasn’t a comfy bachelor pad—there was no Mrs. Ra—more like a mystical alternative to NASA’s Mission Control.

The application to designate the Institute as a historical landmark notes that, after Sun Ra’s death in 1993, his musicians continued to live there “surrounded by his artifacts and aura.”

Of course, Sun Ra didn’t really come from Saturn. He was born as Herman Blount in Birmingham, Alabama in 1914. But if his cosmic shtick was a clever marketing angle, it was also something much more. He lived his chosen role with such dedication that you couldn’t really tell where Herman Blount ended and Sun Ra began.

I’d love to provide a more complete history of Sun Ra’s 45 rpm singles. But even the experts don't know much. I consulted Lord’s Discography for release information, and it tells me that “I Am Strange” was recorded at an “unidentified location” in the “early 1950s.”

Sun Ra fans have grown used to these mysteries. Perhaps they even cherish them. Sometimes the band sold albums at gigs—but they were often unmarked in white sleeves. Even your local dealer of contraband provides more details on the package than Sun Ra, whose music seemed to exist outside the boundaries of time and place.

We have even less information about Sun Ra’s follow-up single “Chicago USA” (with “Spaceship Lullaby” on the flip side). Here the discography tells us that the music was recorded between “1952 and 1962.” So we don’t know if its pre-Coltrane or post-Ornette.

But that hardly matters, because Sun Ra puts jazz aside here to present a permanent theme song for the Windy City, perhaps suitable for a tourism campaign. Let’s just hope those tourists like polytonality alongside their deep-dish pizza.

Experts can’t even agree on how many singles Sun Ra released. In the liner notes to the definitive compilation of Sun Ra 45s, Francis Gooding claims that “perhaps there were nineteen singles in all, perhaps twenty. Or perhaps not.”

So this music is, by definition, timeless, although perhaps not in the usual meaning of that term. Nobody knows much about when it was made.

But it’s timeless in a more poetic sense. I’m referring now to the peculiar hodgepodge of stylistic elements which don’t seem at home in any decade. Even when Sun Ra tackles a familiar song, such as the Gershwin brothers “A Foggy Day,” originally from 1937, he delivers something more akin to astral doowop than to anything George and Ira would recognize as their own.

But just when you least expect it, Sun Ra serves up danceable R&B tracks—such as “I’m Coming Home” and “Last Call for Love.” These actually might have achieved radio airplay, if any deejay was paying attention to our dear Saturnian bandleader. And later singles covered everything from intense bebop (“Medicine for a Nightmare”) to love ballads (“Bye Bye”) to holiday music (“It’s Christmas Time”). At one point, Sun Ra even recorded “Great Balls of Fire”—but it bears no relationship to the Jerry Lee Lewis hit of the same name.

Sun Ra really couldn’t do any genre without messing with it. Even when he released a disco song he gave it a futuristic angle and name (“Disco 2021”)—and in an odd way seems to anticipate the Daft Punk sound of the year in the title.

“Outer Space Plateau” is clearly in the Afrofuturist camp, and could provide the soundtrack to a surreal sci-fi film. I’m told this 45 came out in 1982. But you’d have a hard time guessing that from the record, which looks like this.

And you though only the Beatles issued white albums.

On the other hand, “The Perfect Man” sounds like a dude trying to rap while underwater, and “Cosmo-Extensions” is pure atonality. Meanwhile “Nuclear War,” which (judging by the title) promises to blow out your ears and subwoofers at the same time, is actually a low-key call-and-response song.

But even as he amplified the intergalactic ingredients in his music, Sun Ra never lost touch with commercial genres on planet Earth. “Love in Outer Space” still pretends to be a love song, but focusing on the cosmic love that hippies and flower children had brought mainstream a few years before. But Sun Ra knew about those astral vibes before the hippies were born.

I would love to provide a unifying theme to this assortment of aural oddities. But there isn’t one. Sun Ra was an experimental artist in the truest sense of the term. Unlike many others who adopt that name—posers who take few genuine chances despite all their posturing—Sun Ra actually conducted real-time experiments in the recording studio. If his laboratory blew up, it was okay. He would be moving on to something else, no matter what.

That gets lost in the Afrofuturist rhetoric. Sun Ra deserves a huge amount of credit for anticipating that movement—and I’ve given to him in other settings. But you still can’t pigeonhole him, even after all the academic conferences and peer-reviewed assessments.

The music business got him wrong when they dismissed him as a novelty act. But the academics also do him a disservice by turning him into some kind of theorist.

We would do better to tease out all the strands in his legacy—and there are enough of them to keep us busy for a long, long time. Sun Ra the risk taker may be my favorite. But he was also a performance artist. And, yes, a king of cosplay. And a bit of a con artist too, but in a lovable kind of way.

Somewhere in that expansive definition we must find a place for his work as a jazz musician, which is how I first got to know Sun Ra. But I’d never pretend that any of these labels—or all of them put together—begin to contain the man.

He was certainly too big for a 45 rpm record. There simply wasn’t enough disk space for him in that constrained format. But I give him credit for trying. And on the astral charts, much higher than the lowly Billboard rankings, those singles will always be home runs.

I'm sure by "death" you mean "departure" ... and wow, Marshall Allen just turned 99, not sure he intends to depart.

My friends and I went to Boston in 1979 to see Sun Ra and the Arkestra live. I was very impressed with a keyboard he played, which instead of making sounds, projected colors onto an onstage screen. He was literally playing colors.

Later that year he came to Hartford and I was able to interview him for my radio show on WWUH. I asked one question, he talked for an hour and a half.

As my career unfolded in New York, I played often with some present and former members of his band, like saxophonists Pat Patrick and Charles Davis. But the story I remember is the one Jackie McLean told me when I was his student: he said when he was 17 Sun Ra approached him and asked him to join his band. Jackie said, "I was afraid of him. I ran away!"