The Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay (Part 2 of 3)

Or, an Experiment in Rock Criticism

Here’s the second part of my extravagantly long “Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay.” For part one (and the background story on this article), click here.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay (Part 2 of 3)

Or, an Experiment in Rock Criticism

by Ted Gioia

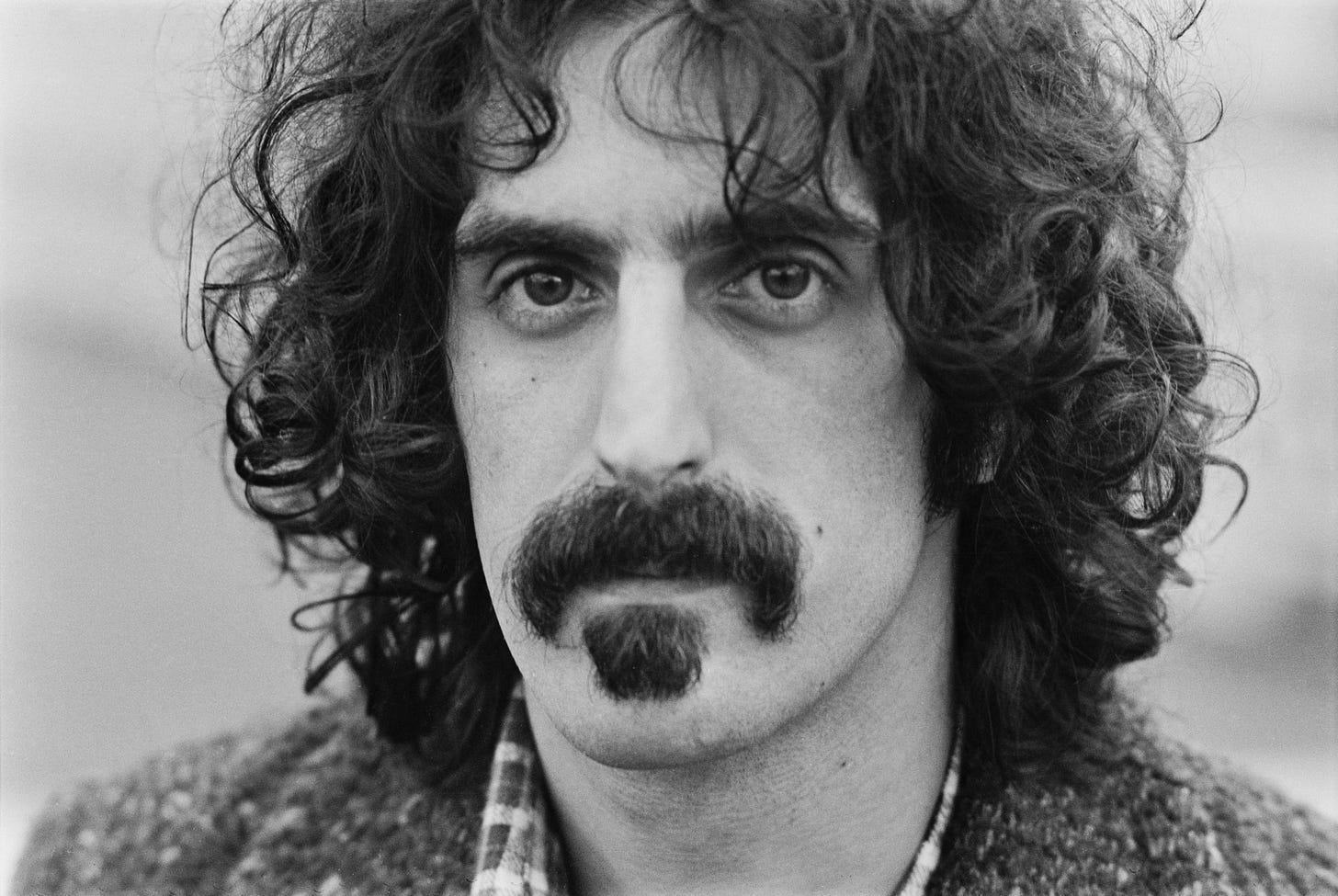

Fans were now getting a closer glimpse of this unusual rock star. That frown, they were starting to realize, was not a pose, but the sign of Zappa’s ingrained scorn for everything, anything, and mister in-between. Maybe he was even a nihilist, straight from the pages of Turgenev. We had thought that Zappa would offer us an undiluted quaff of ‘Sixties liberation, but in fact he had much more in common with our Dad than we had ever realized. (“We were so sure it couldn’t happen HERE.”)

In a strange twist, the Mothers were the first to discover his uncanny resemblance to fathers. Zappa was a strict taskmaster, demanding practice and perfection from his employees. You might even call him a martinet, a hardass, a workaholic—as his huge body of recordings testifies. Somehow he’d gone from Freak Out! to control freak while we weren’t looking, obsessed with creating more and more music rather than indulging in the permitted excesses of the rock scene.

Zappa not only scorned drugs himself—the exact opposite of the public’s image of him—but disapproved of his musicians’ use of mind-altering substances. And with regard to. . . hmmm, sex. . . Well, listeners should not be misled by the explicit lyrics and Zappa’s apparent obsessive interest in the varieties of copulative experience. More to the point is the attitude of ridicule and sarcasm with which he treats the subject. You keep doing that buddy, and you’ll come down with a bad case of Pacoima. If it wasn’t for the borderline (or, let’s admit it, way-across-the-border) obscenity, one might even think him a prude. For the record, Frank Zappa eventually celebrated his twenty-fifth anniversary with wife Adelaide Gail Sloatman—quite an achievement for any rocker, but especially for one who died at age 52.

You might even write a business book with some ridiculous name such as Frank Zappa’s Management Techniques. Rock stars rarely have their own act together, but none matched Zappa as a drill sergeant for new rock recruits, whipping the bandmates into shape, kicking their butts the moment they fell out of line. In a ranking of musicians with intimidating stares, he’s up there with Miles Davis, Benny Goodman, and Ludwig van Beethoven. And though he usually had some of the best musicians in the rock world on his payroll, he never hesitated to complain about their limitations, point out their mistakes, and give out compliments in the smallest of doses.

Yet the music itself offered a chastisement even more biting than anything Zappa could say in words. These were tough songs to play, and many rock “legends” would have been given permanent maternity leave from the Mothers after the first week on the road. But this was a strange kind of complexity, one that coexisted with the simplest building blocks of music.

Zappa mocked rockers who released track after track based on ii-V vamps—he sarcastically called it the “Carlos Santana secret chord progression.” Yet Zappa himself loved soloing over just two juicy chords, or even less, say a drone in 4/4. Then again, it was often hard to tell what, in the Zappa universe (Zappaverse?) was parody and what was genuine self-expression. Sometimes it seemed like Frank didn’t differentiate between the two.

And the moment you thought Zappa was pursuing a personal vision of garage band jams or camp-for-camp’s-sake, he would throw out something jagged, dissonant, and full of shifting meters—such as “The Little House I Used to Live In”—19 mind-blowing minutes of music recorded in the late 1960s. Can you even call this rock? Hippies are advised to head for the hills, and find one of those bomb shelters people were building back then. There weren’t enough joints in all of Berkeley to make this music seem mellow.

By the same token, Zappa dug those minor pentatonic licks with the enthusiasm of a first year student at Berklee. But this was misleading, too, because he could switch gears in a heartbeat and embark on some ridiculously convoluted piece of musical acrobatics, or even veer into the furthest reaches of the avant-garde.

Jazz pianist Paul Smith once described a recording session where Zappa grew frustrated at how poorly the hired musicians were playing his complex scores—so he made up a new aleatory composition on the spot. He put the session players in a circle and sat on a chair in the middle, from which he would point randomly at a musician, who would then make a noise on an instrument. Yet on a different day, Zappa would be just as likely to take the whole squad and force them to play 12-bar blues in every key. The only constant in his routine was that there was no constant routine.

I’ve heard rock musicologists (I’ll admit it—I made up that term) debate endlessly whether Zappa is more partial to Lydian or Mixolydian modes. Hey, whatever floats your boat. But I’m not going down that rabbit hole, because the real essence of Zappa’s music wasn’t the individual ingredients, rather the juxtapositions. He was deliberately pursuing a postmodernist cut-and-paste ethos before anyone else in rock, and almost anyone in academia. This inventive Mother was like a matchmaker who pairs up incompatibles in zany marriages for a sadistic TV reality show—only with Mr. Z. it was sounds not singles who ended up in deviant intercourse for the voyeuristic audience.

Above all, Zappa’s music stood out for its freedom—that was his genuine F word. From a purely technical point of view, you could analyze the musical freedom, the polyrhythms and odd metrics and bar-crossing acrobatics. The free fluidity of the superimpositions is what makes this guitarist burn, baby, burn. But it went hand in hand with Zappa’s stylistic freedom, which acknowledged no boundaries. Even the quirkiness of his guitar technique, all those strange picking and finger sounds, add to the overall effect. Frank Zappa played wrong and made it sound righteous.

But he needed to find musicians who could keep up with the boss. The end result of all of this was a push for what organizational experts call peak performance. And more often than not, Zappa achieved it. By any measure, he was one of the great bandleaders of his era—with an emphasis on the word leader. Yet few of his fans would have guessed it. Some probably even thought he was just another hippie on acid.

A few onlookers, however, were starting to sniff out the truth. Zappa had promised Dionysian liberation, but at a far deeper level he drew his energy and stage presence from the Apollonian control-and-command toolkit. In the Freudian drama, he ought to be cast as the punishing Father of Prevention, not the warm-and-fuzzy Mother of Invention. Even rock fans without psychoanalytical training were now comprehending that the satirical nihilism of We’re Only in it for the Money was a poor fit with the peace-and-love ambience of the era.

Maybe even Zappa realized it. In any event, he put his Nietzschean will-to-power sensibilities on the backburner for a short spell—although they would eventually take over as the dominant element of his worldview. In the interim, Zappa explored an impressive range of expressive mediums in the closing years of the 1960s. He moved masterfully from the doo-wop inspired sounds of Crusing With Ruben and the Jets to the surreal soundtrack to the movie-that-almost-wasn’t Uncle Meat. He shifted gears from the philharmonic aspirations of King Kong to the jazz-rock inflected masterpiece Hot Rats. And he still found time to launch the counterculture careers of Captain Beefheart—serving as producer for Trout Mask Replica, arguably the strangest album of 1969 (no small claim, that)—and Alice Cooper, among others.

Oh, don’t let me forget: Zappa also took a stab at writing TV commercial music, and won a Clio Award in the process.

This was an era of tremendous expansion in rock music, but no one was engaged in a more extreme land grab than Frank Zappa. Uncle Meat and Hot Rats rank among Zappa’s finest efforts, and gave notice of his growing interest in other cutting-edge developments from jazz-rock fusion to musique concrète. The former album, from 1969, is a wholly satisfying project, even without the cinematic accompaniment Zappa intended. His guitar work takes on an accomplished flamenco fluidity in “Nine Types of Industrial Pollution,” and “Ian Underwood Whips it Out” is even more daring, an indecent exposure of free jazz, as pleasing as it is unexpected on a rock album. On “Dog Breath, in the Year of the Plague,” Zappa plays one of his standard tricks, combining a luscious, yearning melody with suburban lyrics of quiet desperation, but he returns to the same thematic material on his short but excellent “The Dog Breath Variations.” Perhaps the most surreal interlude is a live snippet from the Royal Albert Hall, where Zappa enlists band member Don Preston to play the venue’s venerated pipe organ—a behemoth dating back to 1871 and once the largest in the world—in an atonal arrangement of “Louie Louie.” In the aftermath, even stiff British upper lips were now bent in a grimace at the mention of Mr. Z’s blasphemous name.

Did Zappa have no sense of decency? The short answer is no.

But Hot Rats aims even higher, and is a genuine masterpiece of jazz-rock fusion. Check out the band’s chops on “Peaches en Regalia.” That piece was so jazzy it even found its way into The Real Book, the canonical compilation of lead sheets that educated the next two generations of rising jazz stars—and a private club of sorts where no other rocker gained admission. The extended version of “The Gumbo Variations” from this same album, a sixteen-minute excursion into high energy jazz-rock, is another major statement, and a sign of how far Zappa was willing to travel beyond familiar rock formulas. The cohesion of the rhythm section on this track stands out, and the solos are impressive—Ian Underwood’s tenor sax solo is major league work, not your typical rocker trying on a pair of over-sized jazz shoes. Zappa himself generates so much smoke-and-flames here, I’m ready to break out the fire extinguisher in the glass display case.

On the basis of these end-of-the-decade projects alone, Zappa was establishing himself as the biggest risk-taker of all the rockers in this turbulent age. One could only echo Lester Bangs, writing for Rolling Stone, who announced at the time: “If Hot Rats is any indication of where Zappa is headed on his own, we are in for some fiendish rides indeed.” Another critic, trying to explain the paradoxical qualities of this music, offered up this thumbnail assessment: Hot Rats “could appeal to a child as easily as it could a stoner, a rocker, or a fan of the avant-garde.”

Despite all this, Zappa had never enjoyed even one honest-to-goodness hit single, not even a deep track that got into regular rotation at the more free-wheeling FM stations. It wasn’t as if he didn’t try. Zappa released ten singles in the 1960s and not one of them made the charts in the US—or any other country as far as I can tell. His album sales were little better. His albums from the 1960s are praised to the skies nowadays, but none climbed any higher than number 30 on the estimable Billboard ranking, and most failed to reach the top 100. Hot Rats, now an acknowledged classic, peaked out at number 173 on the Billboard top 200. Even in the tiny subgenre of vermin music, it couldn’t match the sales of “Theme Song to Ben.”

This is the context in which we need to view Zappa’s decision, in the early 1970s, to dig more deeply into jazz. Didn’t he know this was career suicide for a rock star? Of course he did—he famously quipped that “jazz is the music of unemployment.” And he had already tasted the bitter fruits himself when he collaborated with French jazz violinist Jean-Luc Ponty on a pathbreaking fusion record back in 1969—complete with liner notes by Leonard Feather and produced by Richard Bock, who had made his name promoting Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan back in the 1950s. In the aftermath, Zappa complained to a journalist: “It’s ignorance. The public is not ready to listen to long instrumental things. They can’t hear them.”

Undaunted, Zappa now embraced jazz-rock with the vengeance of a Las Vegas loser hoping to defy the odds at the craps table. These explorations delivered no jackpots, but did result in two very underrated recordings, Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo, both released in 1972. Their impact at the time was negligible—fulfilling Zappa’s caustic views of the listening public. But the sad truth is that jazz insiders were just as skeptical of Zappa as parents, ministers, and the plastic people he once sang about. This was the golden age of jazz-rock fusion, but only musicians who came out of the jazz side of the equation were getting praised in the prevailing narrative. So if you asked a jazz devotee to list the leaders of the fusion movement, you would hear about Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Joe Zawinul, John McLaughlin, and Wayne Shorter, among others. But why not Frank Zappa or Joni Mitchell or Steely Dan or Blood, Sweat and Tears? Those latter artists were just as much fusion stars as the former, but were strangely denied even a tiny dose of jazz street cred at the time.

In all fairness, everyone was having trouble keeping up with Zappa at this juncture in his career. He seemed to be everywhere during the latter days of the Nixonian empire, except perhaps where big money is made on the music scene. Even a single album such as Weasels Ripped My Flesh, released in 1970, would cover more ground than any critic could traverse. “Anything goes” said one reviewer, and “aggressively bizarre” griped another.

Such confusion was understandable. If you peered under the hood of his music at this juncture, you would see the most unlikely assortment of moving parts—Luciano Berio, boogie woogie, Eric Dolphy, Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown, Neal Hefti, Claude Debussy, “Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, Edgard Varese, and others equally incongruous spark plugs—firing the pistons of his rock ‘n’ roll engine. In a few years, this mix-and-match aesthetics would get legitimized and academicized (and ultimately lobotomized) under the rubric of Deconstruction with a capital D. But at the end of the 1960s, only a few bohos in Paris knew about all that, and apparently they weren’t buying many copies of Weasels Ripped My Flesh. This was Zappa’s tenth album, and he should have serious tailwinds to his career by now, but it peaked out at number 189 on the estimable Billboard chart.

Who could see Zappa clearly now? Maybe not even Frank himself.

But, as the 1970s would prove, Zappa’s ears were getting bigger—metaphorically speaking, that is (physically, they had always been humongous, but usually well hidden under a tangle of hippie hair). He could hear what he wanted, and often what he wanted was well beyond the conventional range of rock. A handful of newer bands were experimenting with the use of horn sections, and Zappa himself had been using sax and trumpet ever since his first album, but now he wanted to push ahead in this direction, showing that the use of reeds and brass required no artistic compromise, no betrayal of the spirit of the Chicago seven in favor of the seven-piece Chicago band, who had started out with deep jazz roots but gradually devolved into purveyors of pop fluff for AM radio. Zappa performances such as “Big Swifty” or “Cletus Awreetus-Awrightus” were almost exemplary in their anti-Steely-Dan ethos, their recondite insistence on pursuing the muse within, rather than the audience out there.

But Zappa didn’t really hate his fans. It’s true that he often worked to please himself in the recording studio, but different rules applied onstage in front of a large audience. There his genuine skills of showmanship took charge. Sometimes he came across as a punishing Freudian father figure who talked dirty and told bad jokes—but there must have been something in the zeitgeist or youth culture that sought out precisely that ungainly formula. In any event, Zappa possessed undeniable stage presence that even the largest auditorium could not dilute. And as a result, his live recordings would eventually emerge as the focal point for his creative juices—something few fans might have suspected until the release of his Fillmore East concert album in 1971.

This is one of Zappa’s finest moments—and I’m not surprised that it reached the top forty on the estimable Billboard chart, which was a big deal for this artist, or at least the label honchos at Reprise. But unleashing unhinged cathartic energies in a densely-populated enclosed space could come at a high price. Audience reaction at a Zappa concert was sometimes unpredictable or even dangerous. On a number of occasions, the music-making ended in riots or other unexpected events.

Six months after the Fillmore East date, Zappa lost much of his equipment in a fire set off mid performance by a fan who apparently shot a flare gun at the ceiling. Just a few days later, Zappa was attacked by a member of the audience who pushed him off stage, causing serious injuries – including fractures, a crushed larynx, and leg and back problems. In the aftermath, he had to use a wheelchair and stopped touring for most of the next year. When he returned to the stage in late 1972, he wore a leg brace and showed a noticeable limp.

As if poor sales of jazz-oriented albums and physical disabilities weren’t bad enough, Zappa now found himself enmeshed in legal problems. He sued his former manager Herb Cohen, who sued him back. His record labels got drawn into the battle, with funds frozen and Zappa losing access to his MGM recordings for a period. After having escaped from the MGM lion’s den, Zappa had set up his own production company but still relied on Warner Bros. for distribution. However, this relationship also soured over the course of time. To get out of his contract, Zappa had to deliver four albums to Warner Bros., which he did by drawing on a mish-mash of tracks from various sources. These were later released by the label in censored versions, and more litigation ensued.

The situation got so bad that Zappa showed up on radio station KROQ in Pasadena one day in December 1977, and played his Läther music, then embargoed because of Warner’s lawsuit, and invited fans at home to make their own pirate recordings of it. With all the legal kerfuffling, the music itself was almost a footnote. The final Warner Bros. projects were issued without Zappa’s oversight and final approval in 1978 (Studio Tan) and 1979 (Sleep Dirt and Orchestral Favorites). These were largely ignored except by his most devoted fans. It didn’t help that Zappa had no interest in promoting releases from his courtroom opponent.

Seeking an escape from this legal minefield, the rock star now launched another indie label, called Zappa Records. His first release Sheik Yerbouti proved the wisdom of this move—it eventually sold over two million copies, and gave a second wind to a career that, just a few months before, had been floundering. Zappa was now focusing more on the comedic elements in his music, but was as controversial as ever. “Bobby Brown,” a misanthropic story song about a cute boy with fetishistic tastes, was a sizable hit in Europe, even rising to the top ten in Germany, but most US radio stations found it too obscene for American listeners. According to one account, Zappa was so puzzled by the track’s success in northern Europe that he considered hiring an anthropologist to study the phenomenon.

From this point on, Zappa’s biggest paydays usually came from his clowning and satirical songs. Yet he resisted this pigeonholing at every turn. As boss of his own label he was determined to showcase his instrumental and compositional skills. In a series of 1981 releases—Shut Up ‘n Play Yer Guitar, Shut Up ‘n Play Yer Guitar Some More and Return of the Son of Shut Up ‘n Play Yer Guitar—Zappa lived up to the promise of the album titles. Here he drew on tapes of live performances, isolating sections of pieces or interludes that showcased his prodigious guitar chops.

On many of the strongest tracks—such as “five-five-FIVE,” “Beat It With Your Fist” and “Why Johnny Can’t Read”—he is matched with unrelenting energy by drummer Vinnie Colaiuta, who is every bit as dazzling as his boss. Colaiuta had languished in lounge bands before Zappa auditioned the 22-year-old in 1978. At that first encounter, Colaiuta performed Zappa’s notoriously difficult composition “The Black Page”—and, no, you don’t need to be Itzhak Perlman to guess that the name derives from the large number of tiny notes on the staff—a piece that only Terry Bozzio had previously mastered, but which Colaiuta played by heart. Even more than the sheer number of notes, the rhythmic subdivisions here would thwart many world class percussionists, but Colaiuta delighted in precisely these high speed mathematics of hide and stick.

Zappa was equally willing to hire a hotshot guitarist, even one who could challenge his own pre-eminence, as demonstrated by the addition of Steve Vai to the band. Like Colaiuta, Vai grew up in an Italian-American household where he immersed himself in music at a young age, later attending the Berklee College of Music. You might think that Vai’s precocious guitar chops were what grabbed Zappa’s attention, but in fact it was his skill at transcribing music that made the first connection. Zappa had been impressed by the teenager’s transcription of the aforementioned “The Black Page” and hired Vai to put various other tracks down on paper. But the newcomer’s ability to play ‘impossible’ or ‘stunt’ guitar parts (as Zappa described them) soon earned him a spot in the band. During his stint from 1980 to 1983 Vai made a lasting mark not only on Zappa’s work, but on the entire rock scene, where he earned respect as a guitar hero in his own right, even while working in the shadow of a legend on the same instrument.

Zappa was in the midst of his last great creative period—in the late 1980s he would shift gears, focusing more on compilations, reissues, and retrospectives than actual new projects. But even with these stellar bands, sales and reviews fell short of what they deserved. His ambitious rock opera Joe’s Garage was called out by Rolling Stone for its “cheap gags” and “musical mishmash,” although the reviewer couldn’t deny its “profound existential sorrow.” Another critic called the work “thin and thrown together.” (On the other hand, Vinnie Colaiuta’s contribution was later chosen by Modern Drummer as one of the 25 greatest drum performances of all time.) The release made a brief appearance in the estimable Billboard Top 100, peaking at number 27.

Zappa was surprisingly indecisive at this stage. Or maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise given that he was now middle-aged and still had never enjoyed a single radio hit in the US, despite a devoted cult following and sold-out shows. He planned a triple-album of live tracks called Warts and All, but scrapped the project at the last moment—explaining that it was unwieldy. Zappa then decided to release a single album called Crush All Boxes, but that also fell by the wayside. Over time, many of these tracks were released, but in compilations that made Zappa seem less like an active bandleader, and more like the carnival curator of his own archival works.

Then, out of nowhere, Zappa enjoyed a hit—the only one of his long career. . . .

That’s part two of the “Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay.” Here’s the link to part three.

There was one musician who slightly flummoxed him. In Australia in the 1970's Gary McDonald's comedy character Norman Gunston interviewed Zappa and jammed with him. At the end Zappa comments that he "went off key". The huge joke that was hilarious to Australians was that he had broken into the news theme of the national broadcaster, the ABC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mUQ00i9rH4

" If it wasn’t for the borderline (or, let’s admit it, way-across-the-border) obscenity, one might even think him a prude. For the record, Frank Zappa eventually celebrated his twenty-fifth anniversary with wife Adelaide Gail Sloatman—quite an achievement for any rocker, but especially for one who died at age 52."

As I recall, he had a mistress living in one of the guest houses in his compound for years, and Gail was just expected to deal with it. Moon has some very bitter stories about the era.

I can't recall the name of the mistress--I think she was one of 70's super groupies, but she's also written about how Zappa kept printing a mailing address on his albums in case you wanted to contact Frank, and this was how they reconnected and the live-in situation evolved.