The Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay (Part 3 of 3)

Or, an Experiment in Rock Criticism

Below is the third (and final) installment of my “Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay.”

Phew! This has truly been a gnarly project for me—it took longer to complete than anything I’ve ever written (including my books), and achieves a wicked, editor-defying word count. It is, in fact, the most in-depth profile I’ve ever done of a single musician.

But I’ll simply call it a “an experiment in rock criticism.”

Here are the links to part one (and the story behind the essay) and part two.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay (Part 3 of 3)

Or, an Experiment in Rock Criticism

By Ted Gioia

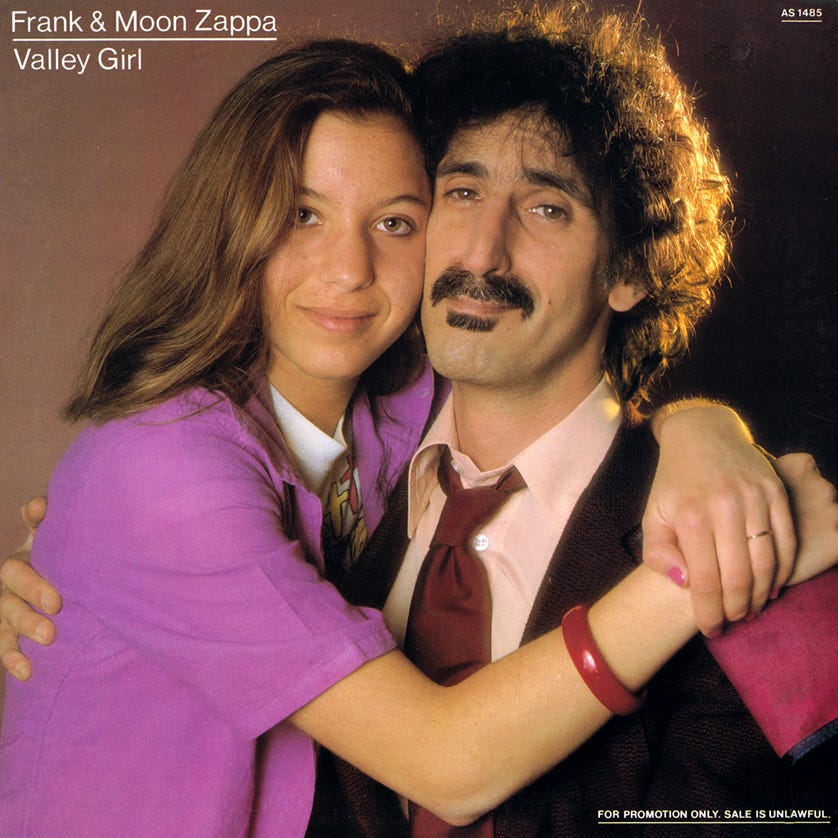

Then, out of nowhere, Zappa enjoyed a hit—the only one of his long career.

Everything about “Valley Girl” was bizarre. It wasn’t just that Zappa had waited until his forties to get into the top 40. Or that he was still fretting about the Valley from the safety of his Laurel Canyon home. Even stranger than these was the fact that the former Mother now drew on his role as a Father to get into heavy radio rotation.

The inspiration behind the song was his 14-year-old daughter Moon Unit Zappa—yes, she was born during the space race, to be more precise, roughly six weeks before the Apollo 4 mission. (Her younger brother, who landed on terra firma soon after Neil Armstrong’s small step missed all that hubub, and thus received the less historic name of Dweezil, etymology uncertain.* But it does rhyme with weasel.) Zappa was fascinated by the slang and vocal inflections his daughter used on the phone with her friends—with all the characteristics that would later get called “Valleyspeak” or “Valspeak.”

[*Correction: Several Zappophiles have reached out to me explaining that Dweezil was named after one of his mother’s toes, specifically the pinky of an undetermined foot. So it’s more precise to say that the etymology of Gail’s toe’s name remains uncertain. It also rhymes with weasel.]

Encino is, like, so bitchin'

There’s, like, the Galleria

And, like,

All these, like, really great shoe stores

I, like, love going into, like, clothing stores and stuff

I, like, buy the neatest mini-skirts and stuff

It's, like, so bitchin'

'Cause, like, everybody's like

Super-super nice. . . .

They hadn’t invented “Bring Your Daughter to Work Day” back then, but that didn’t stop him from taking his verbose offspring to a recording studio late one night. Here he asked her to recreate her distinctive patter in a freeform monologue. Dad added a guitar riff and simple refrain.

You might think this was just one more Zappa laugh at the expense of San Fernando Valley residents. But now in the 1980s mainstream Americans across the land were ready to laugh with him. He had his first (and last) top 40 single, but that hardly does justice to the impact of “Valley Girl.” The song inspired sociologists, linguists, and cultural commentators of various stripes, leading to jokes and stereotypes at one extreme, and peer-reviewed academic scholarship on the other.

Even worse, people still talk like this. And not just in the Valley.

Of course, these linguistic tics were hardly new or unnoticed—surfers and skateboarders far away from the Valley had been speaking like that during my LA childhood. The word grody even shows up in the Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night back in 1964—and perhaps derives from the Middle English groti (slimy, muddy). But it took Zappa’s song to define these concepts as Valley Talk for everyone else.

Our proud father would enjoy one more taste of crossover fame, and it wouldn’t require a guitar or any musical instruments. Instead he had to do battle with other parents—emerging as an ardent proponent of free speech in the face of expanding attempts to censor song lyrics in the mid-1980s.

Zappa took this cause seriously. Perhaps he even welcomed it. In any event, he finally had a target worthy of his satirical talents—a skill previously focused primarily on suburban angst of the lowliest sort along with various shallow simulacrums of modern life. In his new guise as political activist, he could take on both church and state, even showing up to confront the US Senate in historic testimony from 1985.

But there was a self-interested angle here. At the same time he was setting himself as the public nemesis for the parents’ group aiming to censor popular music, Zappa was in the midst of a negotiation to release his catalog on the Rykodisc label. The financial value of this deal—as well as in the eventual sale of most of the Zappa catalog to Rykodisk in 1994—would have been considerably lessened in a more restrictive environment. The terms of the latter transaction were never announced, yet the label had recently completed a $44 million corporate restructuring, and it was easy to conclude that a not insignificant portion of this capitalist lucre was destined for the Zappa estate.

No genuine Zappa fan wants the bad words bleeped out, so he needed to keep them unbleeped. The result was a rare “Mr. Zappa Goes to Washington” intervention.

Yet it would be unfair to accuse Zappa of merely mercenary motives. His anger and zeal were so intense, his self-righteousness at such a high pitch, that only a deep emotional commitment to the cause could explain it. To be fair, Zappa had suffered more from censorship than any rock star of his day, even going back to his incarceration at age 23 in San Bernardino.

His later fame hardly mitigated his problems—Zappa’s whole career was littered with recordings that got shelved, lyrics that got changed, concerts that got cancelled. Even the name of his band resulted from the fear of public backlash: Executives at MGM refused to believe that any self-respecting deejay would play a band called the Mothers, and their squeamishness led to the happy compromise of the Mothers of Invention. (Zappa’s later, oft-quoted quip: “Out of necessity, we became the Mothers of Invention.”)

The built up frustrations of a whole career spent in these battles raged to the surface when Zappa learned about the machinations of the Parents Music Resource Center, an activist group determined to clean up the airwaves and vinyl grooves of America. Tipper Gore led the attack, ostensibly as a concerned parent, but perhaps even more calculatedly as the spouse of a future Presidential candidate. Gore had awakened from her dogmatic slumber after listening with her daughter to the Prince song ”Darling Nikki” from the Purple Rain soundtrack. In conjunction with several other “Washington wives”—most notably Susan Baker, Pam Howard, and Sally Nevius—Gore launched the PMRC in May 1985. The group pressured media and retail businesses to join in their crusade, and their efforts led to the initiation of Senate hearings in September 1985 on the so-called “porn-rock” issue.

What’s the craziest rock photo of all time? You punks can brag all you want about Sid Vicious’s mugshot or Paul Simonon slamming his guitar into the stage at the Palladium. Yawn! For my money, nothing gets more surreal than seeing Frank Zappa testifying before the US Senate. How did he even get through security and into the building.

Rock is a gnarly music. Zappa was a gnarly artist. But nothing gets gnarlier than this.

Zappa was one of a handful of rock stars to testify in this highly charged setting. He was perhaps a less sympathetic advocate for the cause of free expression than John Denver, who also appeared before the committee, and whose woeful tale of mis-interpretations of his song “Rocky Mountain High” as a pro-drug anthem were bound to appeal to Middle America. Zappa, in contrast, was caustic and scornful, raring for a fight.

In his prepared statement, he staked out his ground. “The PMRC proposal is an ill-conceived piece of nonsense which fails to deliver any real benefits to children, infringes the civil liberties of people who are not children, and promises to keep the courts busy for years dealing with the interpretational and enforcemental problems inherent in the proposal's design.” Zappa also took the fight to the people in appearances on the TV show Crossfire, where he debated opponents, and showed a level of conviction and sincere eloquence—on at least this issue – that had rarely surfaced in his cynical and irony-laden recordings.

But Zappa the artist was not asleep at the wheel during this period of political activism. He even integrated extracts from the Senate hearings into his recording “Porn Wars,” featured on the release Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention. It was hard to escape the conclusion that Zappa was thriving in the face of this unexpected opposition from the Washington wives. Like a TV wrestler, he needed a colorful opponent to get his own juices running, and now that he found one, he was determined to make the most of it. Tipper Gore may not have been the boogeyman, and was a poor stand in as the American Joseph Goebbels, but Zappa had to take his adversaries as he found them. And as an artist who required an attack point, even Tipper was a godsend.

After 1984 Zappa mounted only one substantial tour—a worldwide jaunt in 1988 that provided material for Broadway the Hard Way (1988) Make a Jazz Noise Here (1991), and The Best Band You Never Heard in Your Life (1991). You could view these as his last hurrahs as an active bandleader. But it wasn’t clear that he even needed a band anymore. He continued to pursue opportunities as a classical composer, and when Zappa discovered the synclavier, a $200,000 system that created an infinite variety of sounds via a Macintosh user interface, he seemed to have reached his personal Nirvana, a round-the-clock orchestra in his own home, which charged no overtime and never went into rehab. For his 1986 release, Jazz from Hell, Zappa relied solely on the synclavier, and earned a Grammy for the impressive results.

And there was so much stuff still sitting on the shelf. The full scope of what Zappa achieved during his decades of relentless touring was not made clear until the late 1980s, when he began releasing material from his archives—a project that continued long after his death. Eventually six double disk releases were issued with the Zappa imprimatur under the name You Can’t Do That on Stage Anymore, usually abbreviated by devotees to YCDTOSA—more than 12 hours of music released between 1988 and 1992. Many of the tracks dated back more than twenty years, and in aggregate provided an awe-inspiring career retrospective of Frank Zappa’s life and times.

Here the relentless, uncompromising, unsentimental essence of Zappa’s character proved its value. Over a period of decades he made unreasonable demands on his musicians, and they repeatedly rose to the occasion. On YCDTOSA, we hear various editions of his band tackle this music, and the treats are everywhere: a 24 minute version of “King Kong; a whole concert from Helsinki in 1974; Captain Beefheart enacting “The Torture That Never Stops” for nine heart-beefing minutes; from the blues to Boulez, all is digested and regurgitated, combined in strange new hybrids.

How could he top this? We would never find out.

In 1990, Zappa learned he had prostate cancer. Although he had experienced some symptoms for years, and undergone various medical tests, doctors failed to make a proper diagnosis until it was too late. There would be no reprieve from this death sentence, but in his final months Zappa continued to push ahead with his composing and archival releases.

You can see how ill he is in his last TV interview, not just in his appearance but perhaps even more in his subdued, chastened attitude—although he continued to smoke cigarettes in front of the camera. "To me, a cigarette is food," he once explained. "Tobacco is my favorite vegetable."

At this final stage, Zappa had somehow grown into a respectable figure in the culture. When his concert work The Yellow Shark was performed in Frankfurt in September 1992, the esteemed composer received a 20-minute standing ovation—but that would be his last public appearance. He lived just long enough to see that work released on as album on November 2, 1993. "Frank governs with Elmore James on his left and Stravinsky on his right,” enthused Tom Waits, who has named The Yellow Shark as one of his favorite albums.

But one month later, Zappa was dead—finally succumbing on December 3, 1993, a few days short of his 53rd birthday. Fans were prepared, at least as well as they could be. Zappa had always been bluntly honest, and that brutal truth-telling even extended to his medical situation. We knew his days were numbered, although it was still a blow when we heard the news.

In a peculiar move, Zappa was buried in an unmarked grave, somewhere on the grounds of Westwood Memorial Park—by some accounts in the plot next to actor Lew Ayres. In death as in life, he keeps his fans guessing, and at a safe distance. I suspect this was Zappa’s own decision, one last taste of misanthropy from an artist who had always bypassed the sugary love songs of his contemporaries in favor of something more biting and sardonic. Or maybe we should call it tough love. In any event, his audience had loved him in return, despite all the frowns and scowls from the auditorium stage.

They still do. Many years have now gone by, and Zappa’s renown has not diminished, not even by the tiniest black mark on that dense black page. If anything, he is taken more seriously in jazz and classical circles than he was during the prime of his career. And in the rock world he is safely ensconced among the short list of guitar legends, the Z name mentioned in the same breath as the wickedest masters of his instrument.

Yet I’m still not sure we have come to grips with Zappa’s legacy, even after all these years. I talk to various people about him, and it’s almost as if each is describing a different musician. I laud him as the great postmodernist of American popular culture, a raunchier, hipper alternative to Jean Baudrillard. But many of my friends have no patience with that kind of talk—for them Frank Zappa is a master of cool rock licks, or a purveyor of prickly avant-garde music, or a Barnum-esque showman for the masses, or some kind of pop culture anti-hero. For one camp, he is a satirist plain and simple, while others listen to the same songs and describe them as scatological low-brow humor. One person will tell me that Zappa is more a composer than a rock star. The next will insist that he’s more of an improviser than a composer. A third person will say his real talent was as a provocateur, and all the musical stuff was just a sideline. I’ve even met people who merely quote his put-downs and quips, and haven’t actually listened to the albums.

He was all those things, and probably some others too. Maybe we will never figure Mr. Zappa out. But did he ever expect that? It’s no coincidence that one of his favorite rock riffs, “Louie Louie”—he made sure all his bands could start playing it at the drop of a hat—was a song that became famous because no one could agree what it meant, although everyone knew that it was nasty and dangerous. Zappa’s whole career was like that—four decades of leaving people puzzled, unsettled, insulted, and vaguely threatened—but still asking for more. He didn’t give a flying beefheart whether we understood, he just wanted us to listen.

And that, most assuredly, we will continue to do.

But there ought to be a monument, too, or even several of them. And screw the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress can suck eggs. And the same goes for all those other pretentious attempts at rock respectability. Mr. Zappa deserves something different.

In short, he ought to be celebrated at all the banal, plasticized places he commemorated in his songs. Face it, that’s where they need him most.

So let’s give Zappa a commemorative plaque at the Pacoima Holiday Inn. Let’s erect his granite likeness facing down the San Bernardino County Jail. Spray paint his image on walls in El Monte and Cucamonga and the “really good part of Encino.” Name a street after him in Van Nuys, a grody park bench in Lancaster, a fire hydrant in Canoga Park. Let’s cast him in bronze at the Sherman Oaks shopping mall, with Frank’s hand pointing to those bitching clothes.

Those are where he belongs, not the Grammy Museum or some Hall of Fame in Cleveland. He belongs among the Valley Girls and plastic people and shallow SoCal sellouts of all denominations. He belongs there to chastise and castigate. He belongs there to cast a scornful eye. He belongs there to make those weasels feel vaguely uneasy, just as he did during his lifetime. And, yes, he belongs there also because those are precisely the places where our frowning, scowling bard of banality will feel most at home.

I think another good monument would be a dental floss ranch in Montana. An engraved stone might read "mental toss flycoon".

Thanks for another excellent article.

Thanks Ted!!! Great read. Of all of those I have never met, I miss Zappa the most. For all the reasons you nailed and a million more.