The Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay (Part 1 of 3)

An Experiment in Rock Criticism

BACKGROUND:

For many years, I avoided writing about rock ‘n’ roll.

I certainly listened to a lot of it—how could you miss it in those days? But my ties to jazz back then were almost matrimonial in intensity, allowing no infidelities, no quickies in the sack with other genres, not even sultry flirting by the water cooler.

But the deeper truth was that I had no clue how to write about rock music.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

One of my guiding tenets as a writer is that every subject dictates a different prose style. I had picked up that crazy notion back in my college days, when I saw how literary critic Hugh Kenner took on the persona of the different authors he wrote about—Joyce, Pound, Beckett, Eliot, etc. With each of his books, he radically transformed his own way of writing. Every subject, as he saw it, dictated its own terms of engagement.

I found that idea appealing—and later tried to apply it in my own work. When I started to write about non-jazz subjects, I worked hard to reinvent every aspect of my writing style—cadence, metaphor, tone, syntax, even down to the smallest details of the text.

A comparison will convey exactly what I’m describing.

Here’s the opening paragraph of my book Delta Blues, where I altered almost every aspect of my writing style to match the requirements of Mississippi in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Delta region of Mississippi is an expansive alluvial plain, shaped like the leaf of a pecan tree hanging lazily over the rest of the state. Stretching some two hundred and twenty miles from Vicksburg to Memphis, it is bounded on the west by the Mississippi River, and extends eastward for an average of sixty-five miles, terminating in hill country, with its poorer soil and different ways of life, and the Yazoo River, which eventually joins the Mississippi at Vicksburg. For blues fans, this is the Delta, although geologists will remind us that it is not the proper delta of the Mississippi River, which is found where the mighty currents flow into the Gulf of Mexico south of New Orleans.

Now compare that with the opening paragraph of my West Coast Jazz book, which required a very different writing style, one that effectively matched the neon-and-pavement vitality of SoCal in the 1950s and 1960s.

Los Angeles has no true neighborhoods—instead its distinctive cultures stretch out horizontally along specific streets. Hollywood Boulevard, Sunset Strip, Mulholland Drive, Olvera Street, Rodeo Drive, La Cienega—these are to Southern California what Greenwich Village and Soho are to New York. They are Los Angeles’ linear neighborhoods, its criss-crossing geometry of local colors. Each of these Southern California streets boasts a unique sensibility, one that defies city limits and zoning laws—a Sepulveda, a La Cienega might cut through a half-dozen separate townships without losing its special aura, although a couple blocks on either side of these thoroughfares city life collapses back into the faceless anonymity of cookie-cutter car culture. Travelers from other parts of the globe, faced with this specifically West Coast phenomenon, can see only urban sprawl—looking for village geography, they miss the stories encrusted alongside the pavement, the flora and fauna of the LA city street.

Unlike the Mississippi Delta, where the landscape is so pervasive, nature in LA merely warrants a cynical comparison in that concluding phrase.

And, a final example—here’s the opening of my book Healing Songs, where I needed to capture both the emotional power of therapeutic music as well as the clinical scrupulousness of a medical subject.

Stop for a moment, and consider the rhythm within. Your heart pulsates at roughly the same tempo as Ravel’s Bolero, an insistent seventy-two beats per minute, some thirty-eight million times during the course of a year. Twenty thousand times each day, you inhale and exhale, mostly oblivious of the process. Each day, your body’s circadian rhythms run through a repeating cycle, with pulse rates and blood pressure rising upon wakening and temperature increasing during the day, declining at night. Even your hours of sleep are comprised of repetitive cycles of around ninety minutes duration. Your endocrine and immune systems run through their own diurnal cycles. Cholesterol, stomach acid, blood sugar, hormones—all ebb and flow at predictable points during the day. Your body, like a musical instrument in an orchestra, must synchronize its performance to the contrasting and complimentary rhythms surrounding it.

You can see what I’m saying. The writing style adapts to the subject matter. At least, that’s how I try to practice my craft.

These were all well and good, perhaps. But I still couldn’t figure out how to write about rock music.

And the more I thought about it, the harder it seemed. I wanted to write in a way that captured the grandiosity and titanic ambitions of the music, but also its shallowest moments of posturing and pretense. I dreamed of sentences big enough to fill a rock stadium, but also with the quiet authority of a backstage pass. I wanted to write with blunt honesty, but also do full justice to the magical mystery moments at the heart of the rock experience. I wanted to do all these things, and put it down in print.

Could I pull it off? Was it even possible?

I was determined to find out. So I started writing an entire book of essays on rock and pop. I even had a tentative title: Unpopular Essays on Popular Music. And I wrote, and wrote—day after day, for months.

And I failed.

I just couldn’t bring this book to completion. I wrote hundreds of pages, and decided not to publish any of it.

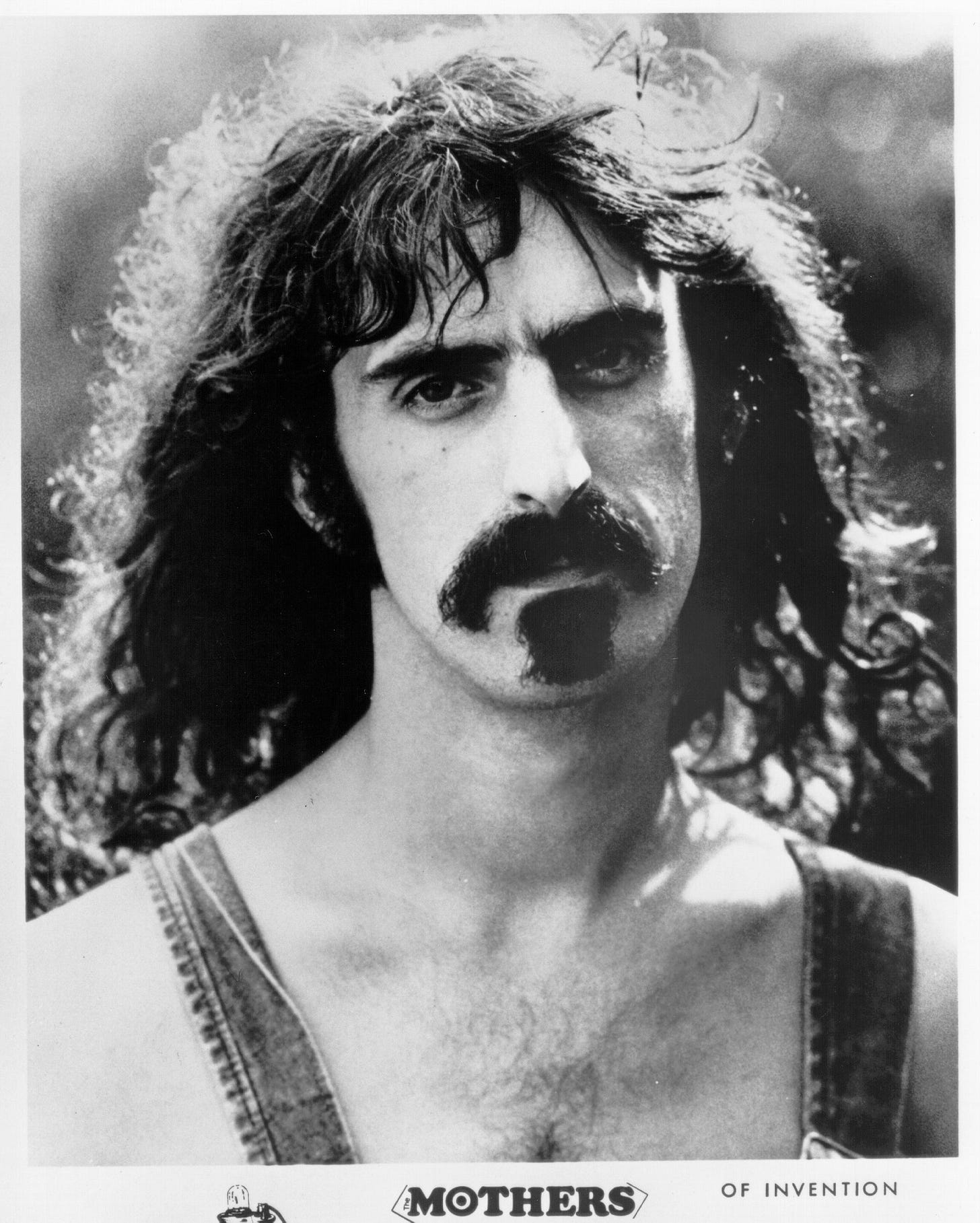

The final breaking point came with a long essay on Frank Zappa—which I struggled over interminably. I am typically immune to writer’s block, but I simply couldn’t finish the Zappa essay. I had met my match, and it was a scowling, frowning man with unkempt facial hair.

This gnarly Zappa essay was supposed to be the centerpiece of the book. It would showcase my new way of writing—custom-made for rock music in general and Frank Vincent Zappa in particular. Instead, this elongated essay came close to destroying me as a music critic.

So I put it aside, and returned to jazz and more comfortable topics. I found my groove again, and it’s no exaggeration to say I was a writer reborn and rejuvenated. I wrote a book called The Jazz Standards, which got positive reviews and sold well. I felt like a hit single spinning at a crisp 45 rotations per minute. Life was good, and Microsoft Word was my friend once more.

But the notion of the failed Zappa essay never stopped haunting me. It was a lasting reproach embedded in my hard drive—both the one in my computer and the one in my head. I felt I had come close to delivering something special, and that if I had kept at it, I might have overcome all the obstacles, or at least discovered my voice, my own personal way of addressing the genre that had defined my generation.

On rare occasions, I showed parts of the Zappa essay to others—only tiny sections, because there was no finished whole. They loved these little fragments, and expressed mystification that I hadn’t published the entire piece. They always wanted to see the rest. But there was no rest to this story. That merely added to my frustration and self-reproach.

Feelings of guilt forced me to return periodically to this failed experiment, and tinker with it—again and again, over a period of many years. And it slowly came together. When I finally put the finishing touches to that gnarly Zappa essay, I realized that nothing I had ever written in my entire life had taken so long to complete.

Instead of celebrating, I just breathed a sigh of exhaustion.

I share it here, but with some trepidation. I’m still hesitant to make any claims for it—so I’ll simply call it “An Experiment in Rock Criticism.” At least I broke out of my writer’s block, and found a way of dealing with this strident genre. For better or worse, I could move on.

It’s a longish piece, and I will share it in three installments. Below is part one.

The Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay (Part 1 of 3)

An Experiment in Rock Criticism

by Ted Gioia

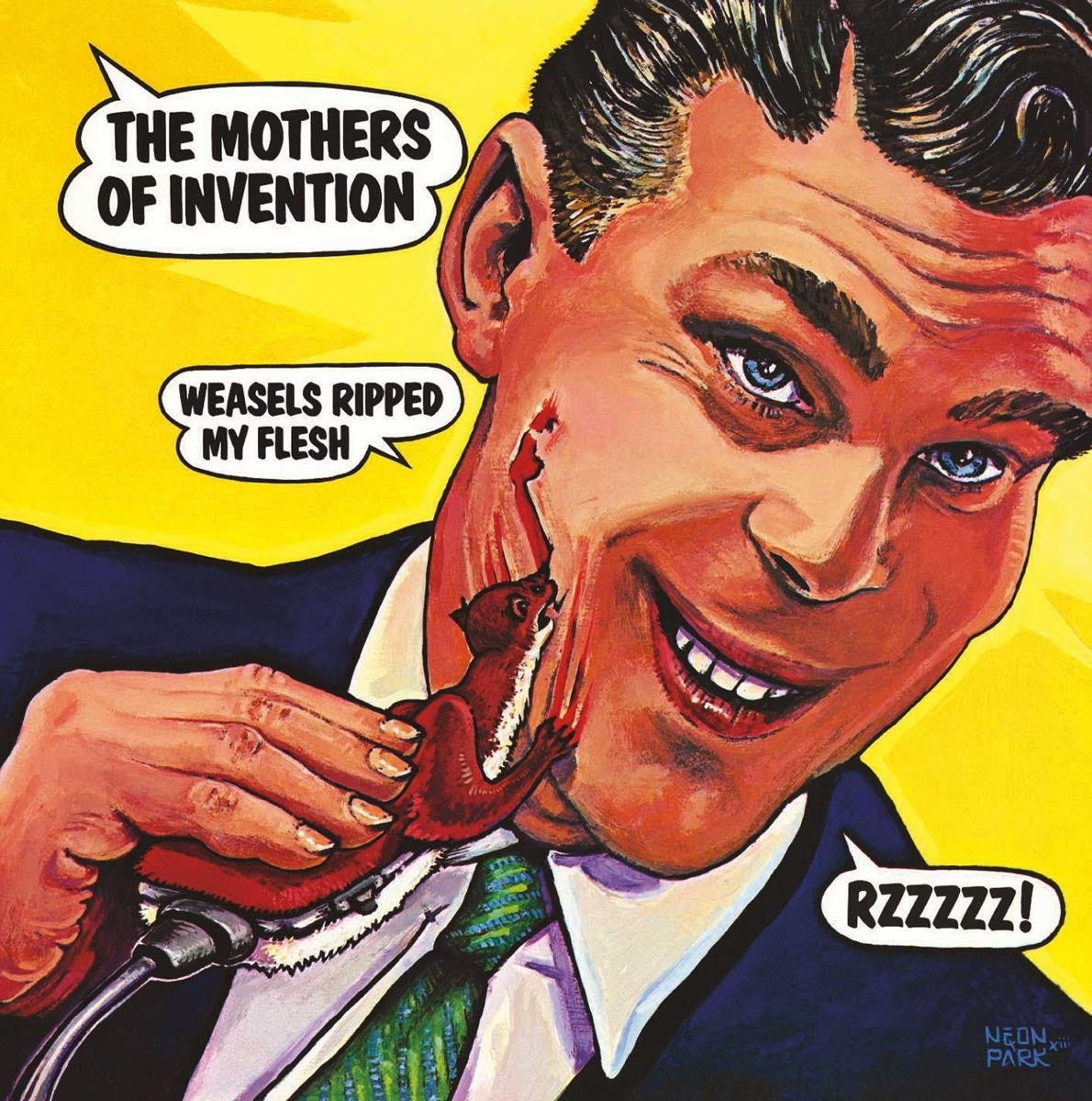

The scowl should have told us immediately. The perpetual frown, matching the semi-circular arc of the bushy mustache, made it clear that this was no party, no summer of love orgy. And in case you might have missed the point, the wry face was under-pinned by another thick brush of whisker below, as if to emphasize the implied criticism, like your home room teacher underlining the grammar mistakes in your last term paper. No performer, since Miles Davis came of age as the anti-Satchmo, glared more often, more penetratingly than Frank Zappa. Read this face, and it proclaimed clear and certain disapproval. Your dad couldn’t match that dour look, even after seeing your latest report card, the dent in the fender of his Oldsmobile, or the newest Mothers of Invention record—Weasels Ripped My Flesh or Hot Rats, let’s say—desecrating his hi-fi turntable, the rotating altar intended for Sinatra, Dorsey, and the original Broadway cast of Oklahoma. If looks could kill, they would look like Frank Zappa.

Bang! Bang! Shoot! Shoot!

What was Zappa frowning at? Well, it hardly mattered. There was so much to disapprove of in the Johnson-Nixon-military-industrial-complex-repressive-computer-punchcard atmosphere. Take your pick: the Vietnam War, the Andy Griffith Show, go-go boots, genuine naugahyde, Reader’s Digest condensed books, leisure suits in pastel colors, Tupperware parties, lava lamps, Bobby Sherman’s picture on the cover of Sixteen magazine, you name it. Something had to burn, baby, burn—a draft card, a bra, the whole freaking dean’s office. Who could blame Zappa for frowning. We would have smiles enough after the revolution.

Zappa was the real deal—or so we ardently hoped. Dali had promised liberation. Robbe-Grillet had promised liberation. Schoenberg had promised liberation. But Zappa delivered. The avant garde, the progressive movements in art were supposed to break through the tired and emaciated paradigms of the past, and open up our sensory paths to brave, new feelings, recharge our central nervous system with a jolt of the latest juice. But too often they did nothing of the kind. The various –isms—surrealism, serialism, solecisms, spoonerisms, you name it, were just . . . well, boring us most of the time. They put us to sleep, when we wanted to be awake like never before.

Zappa never anesthetized his listeners, even when performing major surgery on their sensory organs. You could accuse him of many things—bizarre or outrageous things, even—but never of boring us. In an era in which the best rock music was always surprising us, offering the wonders of a White Album, a Pet Sounds, or Dylan going electric at Newport, no one pushed the “Aha!” further than Zappa. Every new Mothers of Invention album promised to blow out the subwoofers of your mind with something never heard before, not just pushing the envelope but tearing it to tatters with the draft card still inside.

The various ingredients were, of course, quite familiar: doo-wop, industrial noise, scatological humor, contemporary classical music, electric guitars, souped-up keyboards, energy jazz, the four food groups (as personified by Uncle Meat, Suzy Creamcheese, Duke of Prunes, and Electric Aunt Jemima, and others of their ilk), and the chords to “Louie Louie,” to name a few. But the way they were mixed together defied all conventional expectations. Hendrix promised liberation. Clapton promised liberation. But Zappa delivered, not just using his guitar as the ultimate slash-and-burn weapon but blasting gnarly monologues and illicit lyrics—the F-word on a 1960s Verve album, really?—that seemed ready-made for inclusion on the banned substances list.

You owned many albums, but you would still keep those Zappa platters at the back of the fruit box even if they weren’t sorted in A-Z order. Those were the ones Dad was least likely to confiscate, imprecate, mutilate, eradicate. Put up the Archies instead at the front, a sacrificial lamb for parental cross-the-Cambodian-border incursions.

How did Frank Zappa prepare for this world-beating career? His formal education consisted mostly of moving from high school to high school—by the age of 15, Zappa had attended six different institutions of mid-level education. He later tried two different junior colleges, none of them adding much to his body of knowledge. “My formal education is a little skimpy,” he later admitted. “What I know is mostly from reading books I got out of the library.” His constant school-hopping did, however, leave one lasting mark. "I didn't have any friends,” Zappa once explained to the Washington Post. “I developed an affinity to creeps, and I've surrounded myself with them ever since."

In time these stragglers, creeps, and desperadoes morphed into something that vaguely resembled a rock and roll band. “These Mothers is crazy,” proclaimed the liner notes to Zappa’s debut album Freak Out! “You can tell by their clothes. One guy wears beads and they all smell bad.” You could tell even more by their music. The opening bars of the first track are vaguely reminiscent of the Stones “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” which had shaken up the scene the previous year. But Zappa merely uses this to set the stage for the uncompromising weirdness of “Hungry Freaks, Daddy.” Where other mop-tops would follow with a huggy-kissy love song, the Mothers then launched into classic Zappa-frown-scowl mode with “I Ain’t Got No Heart,” which takes us to “Who Are the Brain Police?” perhaps the most eerie and unsettling rock piece one could find in July 1966, when Freak Out! was presented for consumption to a Middle America still trying to come to grips with long haired boys brandishing electric guitars. By the time listeners got to “It Can’t Happen Here,” the word collage paean to paranoia on side two, they must have been reeling in Kansas.

Few got that far, however, or heard much of Freak Out! It took six months before the Mothers’ debut album staggered on to the estimable Billboard chart at #139. It peaked at #130. Then disappeared from view.

What was the respected Verve label—which had built its reputation on Ella Fitzgerald and swing-to-bop jazz—doing with these unkempt dropouts who couldn’t sell vinyl or write a sweet hit single? Parent company MGM had been played for fools. That was no surprise—these were the same industry tyros who thought popular music began and ended with Connie Francis, and when they finally decided to get involved with the British Invasion, made a sucker bet on Herman’s Hermits, while shrewder competitors backed Beatles and Stones.

But if MGM lacked vision, record producer Tom Wilson, who brought the Mothers on his date with the label, knew what he was doing. Wilson was a newcomer to MGM, but had already produced artists as diverse as Bob Dylan and John Coltrane, and around this same time signed the Velvet Underground. His advocacy led to a $2,500 advance for the Mothers of Invention, and a surprising commitment to release a double album for an unknown band, at a time when even established stars were limited to a single platter at the musical buffet. Wilson wanted to test the limits, and with Zappa and the Mothers he found the perfect vehicle for doing this.

That said, the Mothers were never quite as out-of-control as their image conveyed. Zappa always demanded top-notch musicianship, and the various units of his band invariably boasted some remarkable, if little known, accomplishments. Few fans would guess, for instance, that Don Preston had gigged with jazz legend Elvin Jones for a year, had toured with Nat King Cole, and not only played the synthesizer, but had actually built one in 1966. Or that Bunk Gardner once performed on bassoon with the Cleveland Philharmonic. Or that Ian Underwood whose father was President of U.S. Steel, had music degrees from Yale and Berkeley.

Zappa, of course, had none of these credentials. His last institutional affiliation had been with the San Bernardino county jail—where the young guitarist was locked up on an obscenity charge. The legal offense: Zappa had used his recording equipment to make a party tape of suggestive sounds, in response to a request from a supposed used car dealer who turned out to be an undercover cop. Jail time in San Berdoo may not look like much on the curriculum vitae, but at least Zappa got a song out of it.

She lives in Mojave in a winnebago

His name is Bobby, he looks like a potato.

She's in love with a boy from the rodeo

Who pulls the rope on the chute

When they let those suckers go.

He's a slobberin' drunk at the Palomino.

They give him thirty days in San Ber'dino.

Truth to tell, Zappa wasn’t much of an outlaw. He’d never kill a man in Reno, not even in self-defense. Instead Zappa’s formative experiences had revolved around everything drab and pedestrian in 1950s California. He grew up in Lancaster, a hot-baked flatland community in the Mojave Desert, almost two hours from downtown Los Angeles. This was not Hollywood and Vine or even Pico and Sepulveda—only non-descript houses, a small main street, a Denny’s coffee shop, Edwards Air Force Base, and some aerospace companies supported by the military-industrial complex. It’s all too fitting that even when Zappa was incarcerated it was in San Bernardino, a community that makes the middle-of-nowhere seem somewhere by comparison. If other artists spend their careers in a quest for authenticity, Zappa went in the opposite direction. He was our poet laureate of the phony, the plastic, the fake, and benighted—a prophet of those inauthentic souls who somehow, in a depressing SoCal variant on the beatitudes, had inherited the Earth, or at least the toasted badlands due north of LA.

Here one finds the roots of Zappa’s fascination with the banal and commonplace which figure so prominently in his music. El Monte Legion Stadium, Holiday Inn, Ralph’s supermarket, Chicken Delight, the shopping centers of the San Fernando Valley (where she just bought some bitchin’ clothes), and TV dinners by the pool: These were to Zappa, what hot surfing spots were to Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys. In point of fact, Zappa mentions just as many SoCal locales in his songs as Wilson does in “Surfin’ USA,” but instead of La Jolla and Redondo Beach, Zappa is singing about Pacoima, Encino, and other centers of landlocked mediocrity.

You can laugh—even the name Pacoima sounds funny or embarrassing, like some kind of dermatological problem. Doctor, I’m pretty sure I’ve got a raging case of Pacoima. [I lift up my shirt] Just take a look at this. But these were Zappa’s sources of inspiration, what a madeleine was to Proust or a skyscraper to King Kong. His attention was drawn inevitably to simulacrums, to whatever was most shallow in the most vainglorious corner of the world.

And even as rising fame gave Zappa access to the more overtly glamorous side of the entertainment industry, he brought his cynicism and outspokenness with him. Every institution from the Grammy Awards to that august deliberative body known as the US Senate was subject to his disdain. And finally when the powers-that-be wanted to give him honors and accolades, as increasingly was the case late in his life, Zappa refused to show any deference in return.

Consider the grand moment when Zappa was invited to give a keynote speech to the American Society of University Composers (ASUC). In the text of the talk, later published as “Bingo! There Goes Your Tenure,” Zappa sets the ground rules in his opening remarks:

“I do not belong to your organization. I know nothing about it. I'm not even interested in it—and yet, a request has been made for me to give what purports to be a keynote speech.

“Before I go on, let me warn you that I talk dirty, and that I will say things you will neither enjoy nor agree with.

“You shouldn't feel threatened, though, because I am a mere buffoon, and you are all Serious American Composers.

“For those of you who don't know, I am also a composer. I taught myself how to do it by going to the library and listening to records. I started when I was fourteen and I've been doing it for thirty years. I don't like schools. I don't like teachers. I don't like most of the things that you believe in—and if that weren't bad enough, I earn a living by playing the electric guitar….

This is Zappa at his most deferential.

He concludes his talk with the recommendation that the organization change its name from ASUC to “WE SUCK.” I am sorry to report that they did not take his advice.

But I’m running ahead of myself. Ready or not, we must return to the 1960s and take up the thread of our story.

Zappa’s follow-up project for MGM, Absolutely Free, embraced these themes of suburban despair as suitable subjects for rock rebellion, especially in the performances of “Plastic People” and “Brown Shoes Don’t Make It.” But the strongest part of this acerbic album may have been the strangest: Zappa’s series of surreal compositions devoted to fruits and vegetables.

Despite its unpromising name, “The Duke of Prunes” boasts one of Zappa’s best melodies, as he himself must have realized, since he would later reuse its theme in other settings. It appears midway, for instance, in his piece “Music for Electric Violin and Low Budget Orchestra,” where it is played with surprising tenderness by Jean-Luc Ponty. It also shows up, in an ethereal orchestral version, in his mid-1970s project, eventually released under the name Läther. “Call Any Vegetable” also stands out. It is, to be honest, one of the best call-and-response rock pieces I have heard, and even the lyrics rise above their apparent inanity when you realize that the song isn’t really about lettuce and rutabagas. “People who do not live up to their responsibilities are vegetables, Zappa later explained. “I feel that these people, even if they are inactive, apathetic, or unconcerned at this point, can be motivated toward a more useful sort of existence. I believe that if you call any vegetable it will respond to you."

If Zappa could find this much symbolic resonance in detritus from the grocery produce section. . . . well, one wondered, what would he achieve when he tackled a meatier subject? Fans unfortunately had to wait two years before Zappa and the Mothers of Invention released Uncle Meat. In the meantime, they contented themselves with Lumpy Gravy, where Zappa took the unconventional role—especially within the rock culture of 1967—of orchestra conductor, still a low-budget ensemble, perhaps, but a much larger one, impressively dubbed by the composer as the Abnuceals Emuukha Electric Symphony Orchestra. This was followed by the Mothers of Invention release We’re Only in It for the Money, Zappa’s ostensible response to Sgt. Pepper’s. Here the derisive man with too much facial hair was finally broaching the “big” themes of the counter-culture movement: peace and love, hippies, police brutality, conflict between generations.

But those expecting social advocacy from Zappa were bound to be disappointed. It may very well be impossible to say what, if anything, Zappa advocated here, but it was fairly obvious what he disliked—pretty much everything! Sure, cops and parents are pilloried. This was the ‘Sixties, after all. But Zappa now made clear that he despised hippies even more than the establishment.

“Who Needs the Peace Corp?” drips with sarcasm while depicting the life of a peace-lovin’ flower child. (“I’m really just a phony but forgive me ‘cause I’m stoned.”) A range of other targets, from politicians to American womanhood, get their share of abuse. Although the music is occasionally gripping, for example on the spirited anthem “Mother People,” the lyrics are mostly a downer—but that was the intended effect. While everyone else was applauding Sgt. Pepper’s and the groovy atmosphere of love, peace, and rock ‘n’ roll, Zappa saw them as just more targets for satire. The lightest, brightest part of the album is the inside cover parody of the famous Sgt. Pepper’s cut-and-paste celebrity line-up.

Fans were now getting a closer glimpse of this unusual rock star. That frown, they were starting to realize, was not a pose, but the sign of Zappa’s ingrained scorn for everything, anything, and mister in-between. Maybe he was even a nihilist, straight from the pages of Turgenev. . . .

[At this point, I’m interrupted by a parent’s voice from the back row: That guitarist ain’t no hippie. He’s a Nietzschean Übermensch and recklessly laying the shameful foundation for the rise of Derrida. . . .]

Me (from the podium): “Hmmm. I see you folks are getting restless and a bit unruly. It must be time for an intermission. Let’s take five. Also don’t forget that I have books and T-shirts in the back for sale. . . .” [The rest is drowned out by grumbling, mumbling crowd noises.]

Fifteen minutes later, after things have settled down, and the unruly parent has been removed by security, I resume. . .

That’s part one of “The Gnarly Frank Zappa Essay.” Click here for part two.

To paraphrase the list inside the Freak Out gatefold: Frank Zappa has contributed materially in many ways to make my music what it is. Please don't hold it against him.

I met Zappa in 1970 after a concert in Wisconsin, when instead of the usual post-gig recreations he spent a bit more than an hour talking to a mixed bag of college student types who somehow found out his hotel room number. From things I've read his personality got a bit more hardened as time and battles built up over the years, and of course there was the serious on-stage assault that occurred later -- and there's nothing wrong with highlighting his Dada skepticism and echoing of unquestioned nonsense with equal nonsense and pointed ridicule as you start out here. It's a genuine aspect.

But.

On that night, after playing a show, with people who were not rock critics or socially important he was extraordinarily generous, and he changed my life and outlook on art. Things he discussed (most of which later became known to those who were interested in him, but which were not common knowledge in spring of 1970.

That he thought drugs were dumb. That's a complex subject, but his simple answer works better than a lot of other simple answers. Helped me.

That he liked the do-wop that I (and most? nearly all?) thought he was parodying as garbage even worse than modern Top 40 music of 1970. And as he did many interviews since, he praised Guitar Slim, who I'd never heard of. Here this germ was planted: you can use simple or incongruous musical ideas as part of a composition, even a complicated one. Eclectic contrast is a crime worth committing!

That many of the routines on stage were not wild guys improvising their head off. He stressed this to me, and from later reading I know that improvisation was part of the mix in various ratios over the years, but when I asked him about that he pulled out a portfolio of scores that appeared to be 200 Motels and that era material where he pointed out exact dialog for Flo and Eddie and multi-stave musical scores.

That portfolio and his pride in it as he showed it to me, and the general attitude he was conveying that night emphasized that he worked hard and intentionally on his art. That I received this message from what I expected to be a devil-may-care anarchic free-spirit, made it immensely compelling! I mean if Don Ellis or John Lewis or for that matter Karlheiniz Stockhausen had tried to make the same pitch I would have thought "Yeah, that's you. I'm not aiming for that."

I could go on. I'm not musically talented -- I have a few less-common skills, but lack many of the common ones. Life and resources have limited my focus and opportunities too. Because I'm non-revenue in my music and must work when I can, I must play or construct all the musical parts most times. But as writer and as a composer my life changed just from that night forward.

May music find a way.

My lord Ted! I cannot express how much I love your approach to writing. Although 90% of my listening is dedicated to "jazz", Mr. Zappa is filed at the front of my cerebral cortex. Cannot wait for parts 2 and 3. Maybe combining all 3 parts will make the water turn black. Cheers.