The Glorious Future of the Book

It's still the best data center of them all

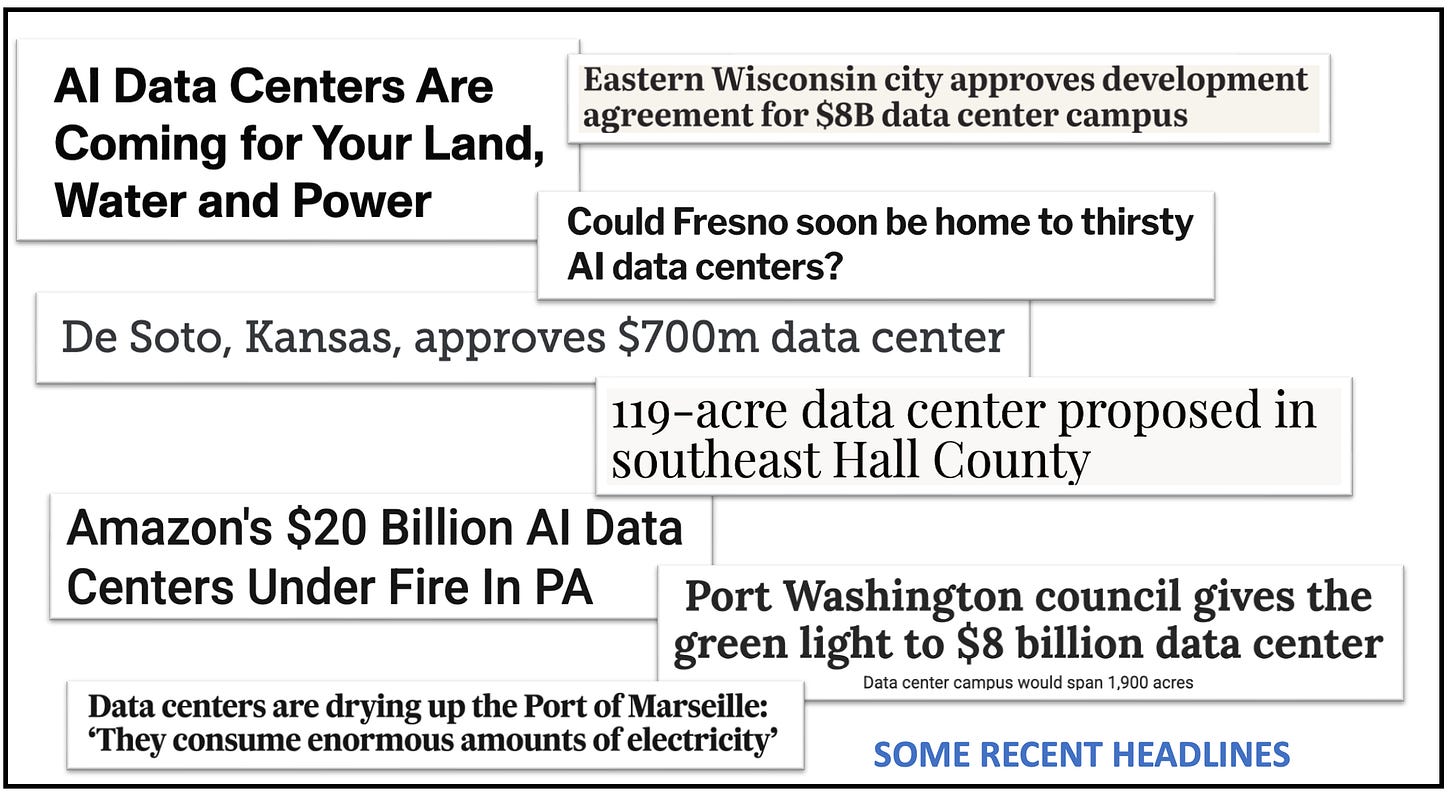

Data centers are in the news nowadays. And not in a good way.

But I have my own home data center. And it requires no water or electricity or any other scarce resource. It’s as renewable as they come.

And that’s just for a start. There are many other advantages.

Can you imagine data storage that never needs an upgrade. Even better, there’s no subscription fee. And the system never crashes—there hasn’t been a single minute of down time in recorded history.

And there’s still more:

There are no terms of service.

No hidden fees.

No customer service bots to deal with.

No annoying follow-up spam emails and texts.

No privacy intrusions or surveillance of any sort.

No data incompatibility issues now or in the future.

No advertising or solicitations of any sort.

The list continues—no cookies, no credit cards, no come-ons, no conditions. None of that.

What a miracle!

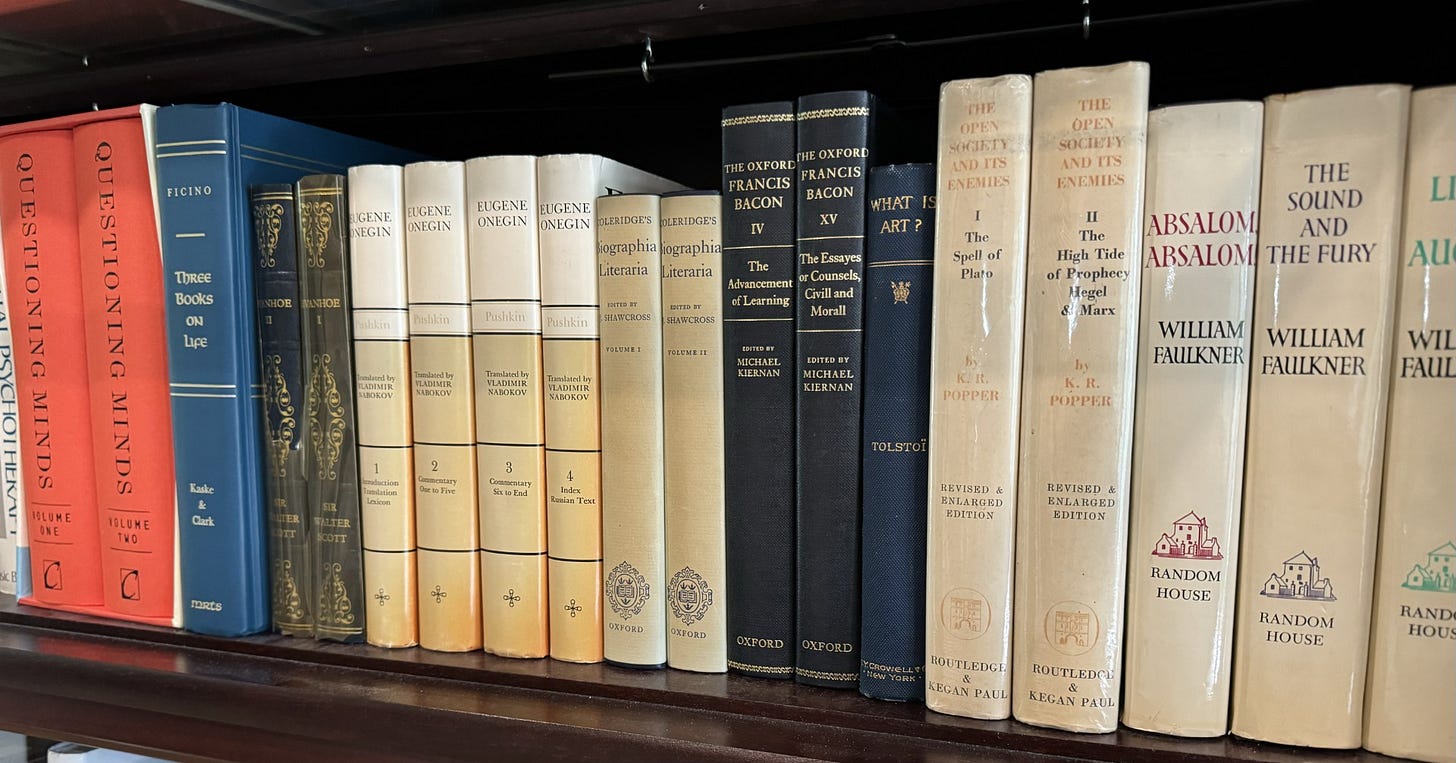

I’m talking about my favorite handheld device, and I don’t need a cloud to hold its contents. Just a shelf.

You guessed it—I’m referring to books. They’re the greatest hard storage concept in human history, and nothing else comes close.

The book is the ultimate killer app.

Please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

People have been predicting the death of the book for decades. The Internet was going to make them obsolete. But somehow they survived.

The launch of the Kindle in 2007 posed a bigger threat. Even I was convinced—at least for a while. I bought a Kindle and tried it out, plunging with enthusiasm into the world of eBooks and digital storage.

But a month later, I’d returned to physical books. It was a better experience in every way.

It didn’t help when Amazon started deleting books from Kindles. Much to the customers’ surprise, they learned that they didn’t own the book they had bought—they were merely “purchasing a license to the content.”

Access can be terminated. And Amazon is the ultimate terminator.

That’s never happened to any physical book on my shelf. I own thousands of them, and nobody has ever revoked my access. I can also sell or give them to others, and they will retain rights in perpetuity.

“The book is the ultimate killer app.”

You can’t do that with a Kindle. You’re not allowed to sell an eBook. You can’t even donate it to a library. Your license is restricted and non-transferable.

But transferability is how books and literary culture survive. Books are supposed to move without friction across generations and borders and boundaries. Some books have had dozens of owners over hundreds of years—creating a legacy unknown in the world of digital technologies.

Even more insidious, Amazon will update books on your Kindle—changing the text without the reader or author’s permission. That’s happened, for example, to books by Roald Dahl, R.L. Stine, Ian Fleming, and Agatha Christie. If somebody in a position of power decides that an author’s work is problematic, your e-book gets cleansed.

“Publishers can issue updates for any reason and generally don’t identify or explain revisions,” warns the New York Times. Many only found out about the cleansing of Christie and others when the changes got reported in the press. In some cases, the books had been stealthily altered years before—and readers simply hadn’t noticed.

Can you see how risky that is?

And it will soon get worse. We are entering a dangerous age when fake media—text, images, videos, audio—are more pervasive than the real things. Deceptive technologies have advanced at a lightning pace, and we still move at a slow, human pace.

That’s our vulnerability. We’re humans.

It doesn’t help that Amazon—the same company promoting eBooks—is also the leader in selling AI knockoffs and slop books. I don’t know if they are just negligent or plain evil, but they are doing irremediable harm to society.

If Amazon is the custodian of books and the literary world, I’d hate to see what an enemy looks like. As soon as any important book is released, the slop shows up on Amazon within hours—knockoffs with similar titles, designed to lure the unsuspecting.

And Amazon is only the most prominent malefactor. Thousands of other companies are also peddling this fakery.

Many citizens are only starting to grasp the threat posed by widespread institutionalized deception. This level of counterfeiting wasn’t conceivable a decade ago, or even a few months ago. But we’re now approaching a tipping point where counterfeits will overwhlem reality, a kind of Gresham’s law for the creative sphere.

In this coming dark age of bogus media, the physical book is more important than ever. My humble bookshelf is a fail-safe bunker where bots and AI agents and intrusive technocrats cannot enter.

Power brokers can now destroy digital documents instantaneously. But they have no power over dried ink on a printed page. Even the most repressive regimes struggle to control physical texts (and don’t think they haven’t tried).

That’s why I envision a glorious future for the book. It solves problems that didn’t even exist a few years ago. And will counter all new threats from digital tech in the future.

It’s our thin dried ink line between reality and deception.

At this same moment in history, I hear experts still predicting the end of the book. At first glance, these warnings sound plausible. It’s true that reading for pleasure has declined. Brain rot from screens is on the rise.

But that hardly matters.

We will soon need to read books for protection. We will need them for survival. We will seek them out because they offer an escape from the degraded digital domains, where duplicity is now dictated by the largest platforms with the richest owners.

Maybe some people think books are boring. But they just might change their minds when they’ve fully grasped what’s coming on their screens.

Go read Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, an oral history by Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich about the end of the USSR. She talked to hundreds of people who survived under totalitarianism, and books were their lifelines.

Books preserved their sanity. Books gave them hope. Books kept them going.

These same books were forbidden. They were seized and destroyed. But it didn’t stop the readers—because they were hungry for a truth outside the control of the powerful.

In those situations, people will risk their lives for a book.

“Books preserved their sanity. Books gave them hope. Books kept them going.”

When things get bad, you don’t need bestseller lists or blurbs or marketing campaigns. The book has a seductive allure that can’t be resisted.

It’s the last safe space for people who care. People who think. People who want something better.

And those people aren’t going away—I suspect there will be more of them in the new age of slopification. So I’m confident that the humble book has a glorious future.

I look at those books on my shelf, and I’m certain these storage units now residing in my home will survive longer than any data center built by the richest billionaire. And if the billionaires were smart, they might start holding on to some books too.

The book is a huge advance technologically over a laptop:

* Has virtually infinite battery life

* Is extremely shock resistant - can withstand a drop of at least 10 feet onto a concrete floor

* Although not extremely water resistant, even after complete immersion the data can eventually be retrieved

* Fully Random-Access,with the ability to add notes

* High contrast display

* Inexpensive compared to a laptop

Don't conflate 'e-book' with 'corporate-controlled licensed (e.g. Amazon Kindle) book'

My wife and I love paper books, we have owned many thousands over the decades, and I have spent many many hours in libraries and bookstores of all sizes, so... it is safe to say I know from books.

But... ever since I had two successive retinal detachments in my right eye seven years ago, regular printed books have been difficult to make out, and I have been 100% e-book. I continue to read as much as I ever have.

If you don't want to be beholden to Amazon or Rakuten (Kobo), it is very easy to purchase e-book files directly from publishers (or in some cases from authors) in the EPUB format that everyone uses these days, download them to the storage and backup media of your choice, and load them into a wide variety of e-reader devices and applications for viewing.