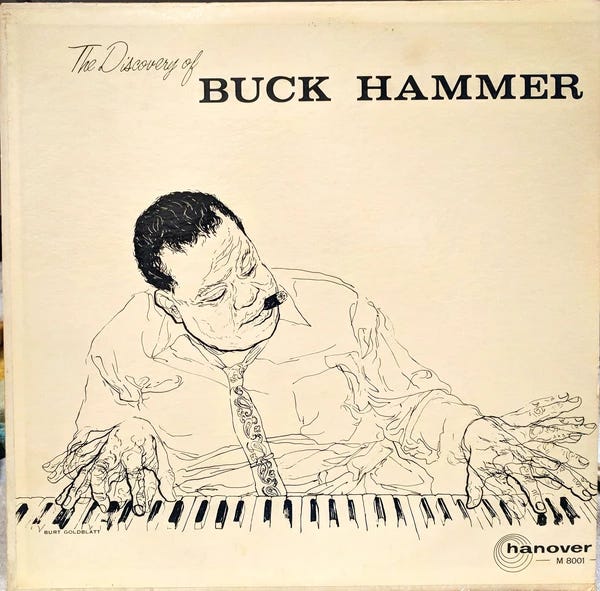

The Discovery of Buck Hammer

A remarkable blues musician emerged from obscurity, but something about him just didn’t seem right

The story of blues pianist Buck Hammer could hardly be more dramatic. After a long career in the honky tonks and juke joints of his native Alabama, Hammer recorded his only album during a 1956 visit to Nashville. He seemed poised to make the leap from obscurity to fame in the final days of his life.

“Buck Hammer for many years refused all offers that would have involved his leaving Glenn Springs, Alabama,” explained music writer Ralph Goldman in the liner notes to this late-career debut recording. “At least a dozen bandleaders and agents of the country circuit are known to have sought him out and made tempting offers and when he finally consented to visit Nashville, in the winter of 1956, to record these few sides he did so with no particular enthusiasm, but as result of a promise made to his brother Martin.”

Blues fans were grateful that Hammer’s sibling had prodded him to visit a recording studio, especially because the pianist died just a few days after completing the session. Shortly after the release of this posthumous album in 1959, a critic in the New York Herald Tribune lamented that “Hammer’s death was a tragic loss to the world of jazz.”

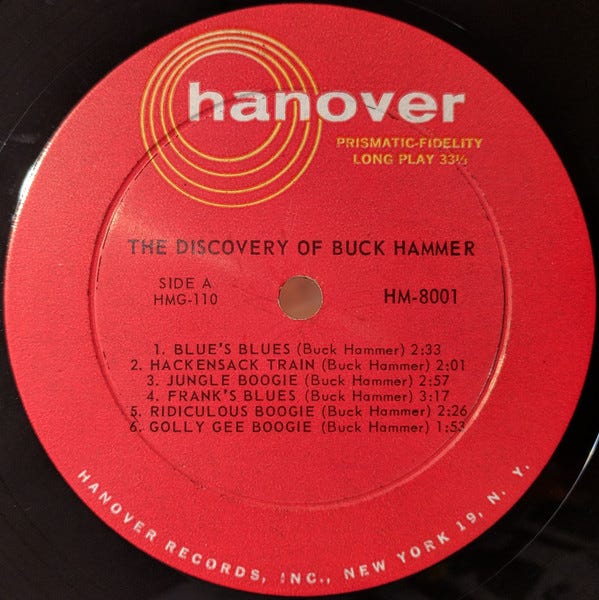

The released tracks showcased Hammer’s prodigious skills as a roots-and-blues pianist with a penchant for boogie woogie. “Some of the left-hand figures seem literally impossible,” Goldman enthused. In the words of critic Gordon Goodman: “Hammer was a true original stylist.”

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The timing for the release could hardly have been better. In 1959, the blues and folk revival movements were in their early stages, and ardent fans were fascinated by vernacular musicians who had received virtually no attention since the 1930s. In many instances it was unclear whether artists such as Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, or Skip James were alive or dead, and their ultra-rare recordings were sought out with passion by diligent collectors.

Over the course of the next few years, the most dedicated of these blues lovers would even go on the road as amateur private eyes, trying to find these venerable performers in the flesh. Some of these artists even resumed their careers, after a hiatus of decades, as senior citizens—discovering to their amazement that, despite years of obscurity, they were now treated as royalty of American music.

Consider the case of Furry Lewis, who made historic recordings in the 1920s, but for most of his life earned his living as a city sanitation worker in Memphis. Yet at the end of the 1960s, he was ‘re-discovered’ and found himself doing concerts with the Rolling Stones and appearing on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

The same might easily have happened for Buck Hammer, had he not died so soon after his emergence from his native Alabama.

But something about his story didn’t add up.

The first warning signs were small ones. For example, why weren’t there any photos of Buck Hammer on his album? Only a simple drawn portrait, vague in its details, graced the album cover. And who were these music critics praising Hammer’s skills. Had anyone ever heard of Ralph Goldman or Gordon Goodman, the supposed experts validating Hammer’s biography and credentials?

It’s possible that the name Ralph Goldman was an allusion to real-life music critic Ralph Gleason. Gleason himself had played no role in the release of the album, but he listened to it with interest, and made a surprising discovery. Some of the passages in Buck Hammer’s music were literally impossible to play—unless the pianist had three hands.

Gleason phoned record producer Bob Thiele, responsible for the Hammer session, and demanded an explanation. Thiele admitted that some over-dubbing had been used on the album, so that two different piano tracks had been combined on the released takes—in other words, this was actually music for four hands.

But there was an even bigger scandal here: none of the piano parts had been played by Buck Hammer.

In fact, there was no Buck Hammer.

On December 14, 1959, Time magazine broke the story. The album had been an elaborate hoax perpetrated by TV celebrity Steve Allen. Allen is perhaps best remembered as the first host of The Tonight Show, still running after 77 years. But Allen was also a skilled pianist and songwriter, as well as a devoted fan of jazz. He not only featured musicians such as Art Tatum or Thelonious Monk on his TV show, but would even give them the opportunity to play three or four numbers. Few individuals in the history of network television have been more supportive of the music.

Yet Allen wanted to play a prank on music writers. He had heard Cannonball Adderley make some derisive remarks on how little critics knew about music, and decided to test that hypothesis. Could he release a fake album by a non-existent musician, and feature tracks impossible for a single pianist to play? Would the critics get fooled?

As a clue, the cover art for The Discovery of Buck Hammer actually showed that the pianist had extra hands.

Despite these giveaway hints, many critics bought into the story. “Downbeat magazine awarded Hammer three-and-a-half stars,” Allen later boasted—a pretty good score for music by an over-dubbed talk show host.

But he also made clear how much the music industry of that era was obsessed with what I have called elsewhere the “Primitivist Myth”—the notion that the best African-American music is performed by untutored performers from the backwoods who make up with enthusiasm for what they lack in proper training. It’s an awkward concept, but a pervasive one, and it probably still exerts an influence over the work of some music writers. The Buck Hammer story, filled with details of an amazing pianist sprouting up on his own in rural Alabama was an ideal lure for critics with this clumsy ‘primitivist’ point of view.

Allen, for his part, had a long history of perpetrating pranks of this sort. Those who have seen the surviving videos of his TV talk show will already know how much he anticipated the unscripted humor of a David Letterman or Conan O’Brien, especially in high-risk skits where unsuspecting real individuals get drawn into the proceedings. Allen, however didn’t restrict these stunts to his TV show, but brought his arsenal of gimmicks and tricks to situations where such zany antics were unknown and unsuspected. In addition to the Buck Hammer scam, he released a similar album entitled The Wild Piano of Mary Anne Jackson—but the only wildness here was the keyboard work of the uncredited Mr. Allen. In other situations, he disguised his own work under aliases such as “French bossa nova composer” Marcel Valentino or poet William Christopher Stevens.

For his Buck Hammer prank, Allen relied on the help of Bob Thiele—who, just a few years later, would produce A Love Supreme for John Coltrane and “What a Wonderful World” for Louis Armstrong, among other now classic projects. Thiele, who died in 1996, published an autobiography a few months before his passing, where he describes Steve Allen as a “one-time business partner, as well as a longtime friend, supporter, confidante, and collaborator”—but he makes no mention of the Buck Hammer controversy. Who can blame him? I’d rather be remembered for A Love Supreme, than for a hoax.

But I can’t really feel outrage against either Allen or Thiele for perpetrating this prank. You can even view the Buck Hammer project as a kind of satire or meta-commentary on the music world. Don’t get me wrong, I’m happy when music fans celebrate the pioneers of the past; but when they fetishize the good old days and revere overly romanticized images of old musicians, they distort and obscure the real history of American music.

The actual history of the music is compelling enough, thank you very much.

My only disappointment is that none of the Buck Hammer tracks are available online. They are not on YouTube or any of the streaming services. Unless you track down a copy of the rare original album, you can’t hear them.

And that leads to the most ironic part of the whole story. That prank album hasn’t been available for more than a half-century. This means that there’s a legitimate opportunity for real Buck Hammer rediscovery and revival. And this time the music has genuinely been in hiding for decades.

I hope your piece will inspire someone to reissue the album.

Steve Allen was a genius.