Is the Middle Class Musician Disappearing?

I look at some gloomy numbers—and offer advice about leading a maximally creative life on a median-level income

The most taboo subject in the arts is how people pay the bills.

Students embarking on careers in creative fields deserve better information and more honest feedback on this subject. But artists are more likely to reveal tawdry details of their bedroom antics than a cash flow statement.

Often newbies are told that baldfaced lie: “Do what you love and the money will follow.” Which sounds great—but also like blind faith in the irrational.

Does the money really follow if you pursue your dream?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Sure, that happens sometimes. But disappointment and financial struggles are more likely. Those of us who teach and mentor young musicians (or other creative professionals) do them a disservice when we refuse to address this subject with candor and practical guidance.

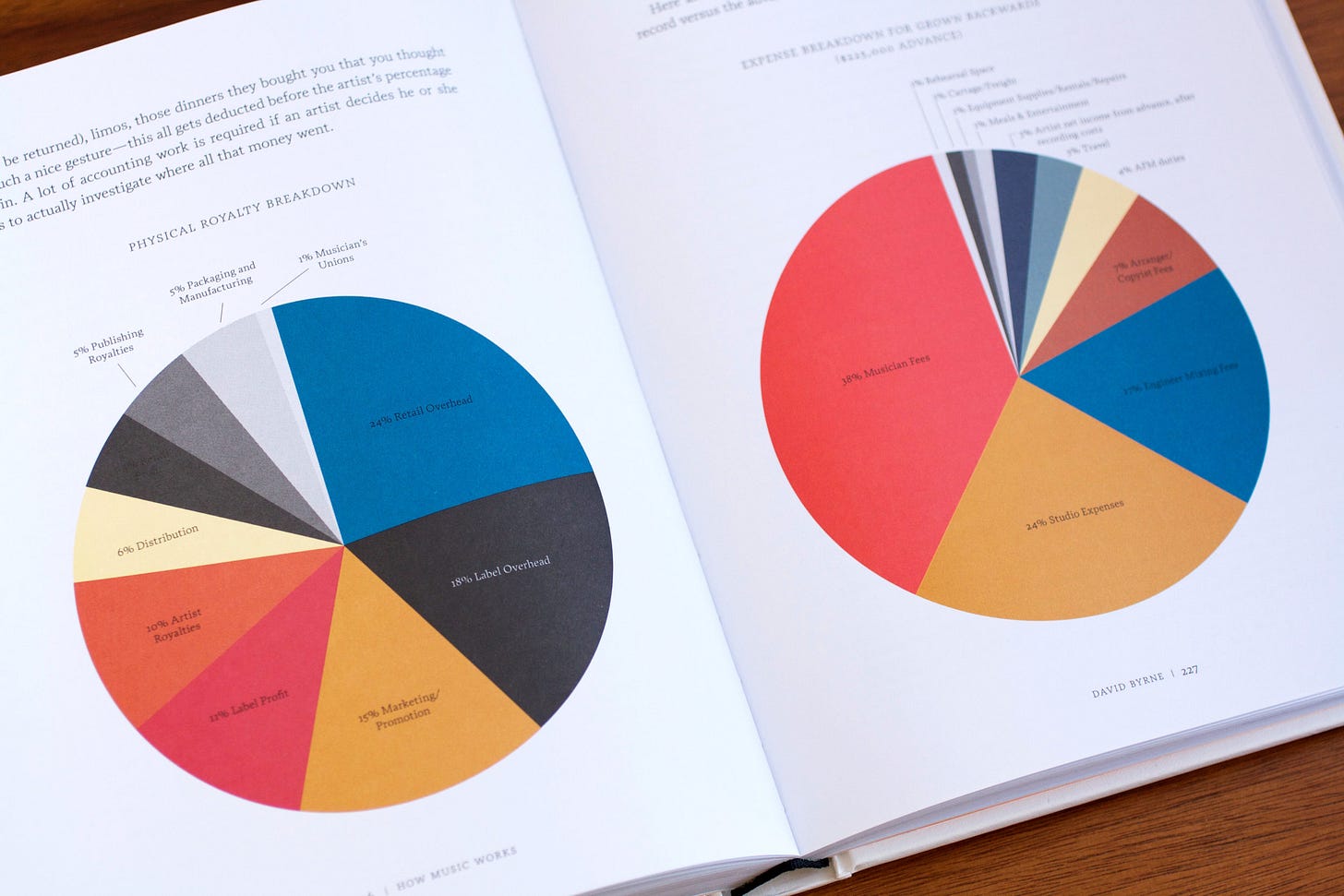

This is why I often recommend David Byrne’s unique book How Music Works. I initially read this book because I admired Byrne as a performer. The last thing I expected was detailed profit and loss statements for each of his major projects. But that’s exactly what he delivered in this book, even summarizing the information in easy-to-understand charts.

We’re fortunate that Byrne was willing to disclose so much information about his financial life. That’s a rarity—and, strangely enough, the taboo is just as strictly observed for both successful and unsuccessful artists. Musicians who make a lot of money are worried that they will look crass and materialistic if they tell people how much they earn. But performers at the opposite extreme are just as tight-lipped, ashamed to reveal how little they make. And musicians in the middle probably feel awkward that they are. . . . well, just in the middle.

Sad to say, there are fewer artists in the middle nowadays. I’m told that only 2% of creators on Patreon even earn the federal minimum wage. It’s hard to figure out how many people are making a middle-class living on music streaming, but I note that you don’t earn the minimum wage on Spotify until you generate more than 3 million streams per year. I imagine a similar stratification is happening to creators on YouTube, TikTok, and other platforms.

In other words, it’s easy to become a starving artist in the digital economy. And a few make enormous sums. But the more modest goal of living a middle-class lifestyle is harder to achieve than you might think.

A survey of more than one thousand visual artists found that the median income was below $30,000—that’s roughly half the typical household earnings in the United States. I note that 63 percent of respondents had art degrees, but on a scale of 1 to 10, they rated their education at only a 5 in preparing them for a financially stable career.

And they have good reason to complain. Only 19% made more than $50,000. In other words, their arts degree was more likely to put them below the poverty line than in the middle class.

Let’s hope they didn’t take out a lot of student loans.

Here’s the most revealing part of the survey: 29% of respondents relied on family financial support or an inheritance to pay the bills. Many needed to take on other work—in fact, only 10% devoted 40 hours per week or more to their art.

This is the real bottom line: Creative pursuits are increasingly turning into playgrounds for those with family money—typically from parents or a partner/spouse who works. That’s not very glamorous, so it’s usually left unmentioned. And journalists won’t ask about it either. They prefer to focus on success stories, not life in the trenches for the everyday working artist.

Much the same is true in my chosen field of writing. When I was starting out, there was a category called the “midlist author”—who operated in that nebulous region between bestsellers and poor-selling failures. The publishing industry has mostly lost interest in those authors, not because they aren’t profitable, but simply because they aren’t profitable enough.

Consider the mindset of the leading commercial publishers—and there’s the appearance that there are dozens of them, but it really boils down to a shortlist of 5 or 6 huge corporations nowadays who have swallowed up most of the familiar imprints. These publishing professionals would rather roll the dice and try to get a bestseller, even at longshot odds, than settle for a solid and profitable book that could reliably generate a middle class income for the author.

That same way of thinking is everywhere. It explains why artsy and indie films find it so hard to get financial backing. The middle of the marketplace simply isn’t exciting enough.

I remember the first time I was hired to help create a pitch for a startup to present to venture capitalists. I was an innocent young pup back then, and labored over all the spreadsheets and charts—and was very excited by what I’d found. My projections showed that a VC’s investment would generate annual returns of 35%. So you can imagine how shocked I was when an older, wiser startup veteran told me: “Ted, those returns aren’t good enough.”

“What do you mean?” I responded in a amazement. “How many investments give you 35% annual return?” “Not many,” my friend agreed, “but venture capitalists would rather chase after a bogus thousand percent return than pursue a realistic three-year payback. You don’t get on the cover of Sports Illustrated by making free throws.”

Sad to say, that kind of thinking has now entered creative spheres. But how creative can you really be if you need to please an enormous mass-market audience? When you go down that path, you need to stick close to all the familiar formulas—and that’s exactly what you see in much of our culture nowadays.

What does this mean for younger artists?

My brother Dana has worked closely with young poets, both in the classroom and other settings. He will tell them frankly: “You need to take money seriously in your vocation.” This may seem like the most obvious statement in the world, but many of them have never heard that before from a teacher.

Dana follows up on the blunt statement with very practical advice, speaking honestly from the heart and drawing on his own experience. We both grew up in a working class family and there was no support net for us if we faltered—unless we knitted that net ourselves. I think it turned out as a blessing in disguise for both of us. The need to pay our bills each month forced us to develop capacities we would not have had otherwise. And we definitely cherished our creative vocations all the more, taking seriously every hour we could devote to them, because we never took that time for granted.

When we finally quit the various day gigs, and focused on creative pursuits full time, we made the most of the opportunities at hand. But that didn’t mean there weren’t sacrifices along the way. Some of those sacrifices were painful and protracted. I’d be lying to you if I pretended otherwise.

I’ve found that students in music programs want this kind of honest feedback. I’m often surprised on my college campus visits how much I’m asked about the workaday jobs I had outside of music and writing. I once thought that those details were the least interesting parts of my life, but I now know the opposite is true. Young artists want realistic guidance, not platitudes.

So I tell them the blunt truth. I would have loved to enjoy the financial independence that would have allowed me to focus entirely on the arts, but how many people really have a trust fund to pay the bills? A spouse with a high-earning career is more common, but I’ll simply say that I married for love, not money, and spare you the details.

So my advice to students interested in the arts is based on my own practice: namely, that they should pursue their craft but also develop at least one money-earning skill before they reach the age of 30. It doesn’t need to be an elite career, merely something that will pay the bills in a pinch.

The second career can even be linked to your art. If you’re a musician, you might learn to tune pianos, lead a school band, or teach lessons. If you’re a dancer like my wife, you might become a Pilates instructor (as she did) or a practitioner of some other body therapy—which can range from recreation therapist (only requires a bachelor’s degree) to physical therapist (graduate training may take another 2-3 years). If you’re an author, you can learn to be a technical writer (median income $75,000) and churn out instructional guides, manuals, etc. I could give you dozens of other examples.

None of this should be surprising. But there’s one thing I want to emphasize. There is nothing shameful about developing work skills and earning a living. People look at composer Philip Glass with even more respect when they learn he worked as a taxi driver, plumber, and in other capacities for many years.

Or consider the case of jazz singer Sheila Jordan, a legend in the field and still active at age 93. She was mentored by Charlie Parker himself, and has won a shelf full of awards. But how many people know that she worked as a typist and legal secretary for decades, and only focused on music full time starting at age 58?

I respect her all the more for those sacrifices.

In other instances, artists needed to learn new job skills later in life after the glamor years were over. I still remember how surprised I was to discover that teen heartthrob Bobby Sherman, who had a number of hit singles when I was a youngster, became a paramedic and worked for a decade teaching first aid and CPR skills at the Los Angeles Police Academy. How can you not admire a teen heartthrob who has the maturity and drive to embark on a life-saving and life-changing second career?

Bobby Sherman shared this amusing story with an interviewer:

"On one call in Northridge, we were working on a hemorrhaging woman who had passed out. Her husband kept staring at me. Finally, he said, 'Look, honey, it's Bobby Sherman!' The woman came to with a start. She said, 'Oh great, I must look a mess!' I told her not to worry, she looked fine."

The paramedics carried the woman to the ambulance, but she made him sign an autograph first. Sherman continued to do occasional performances until 2001, but he didn’t need to rely on nostalgia and fading memories for his sense of self-worth and pride in his vocation. He was having a positive impact every day, and teaching others to do the same.

Not every artist has the makings of a paramedic. But each of has some untapped potential beyond our creative life, and good reasons to develop it.

This kind of flexible approach gives an aspiring artist the best shot at enjoying a genuine middle class income. Maybe they will hit the highest reaches of success and never need to apply those workaday skills. That happens for a few people, and I applaud them along with all their other fans. But they may actually be missing out if they never develop those other capacities.

They might even be better artists for having led a more expansive life. Few of them hear that message when they are embarking on a career in music or writing or the other arts, but they really should.

I started out in college as a performance major, wanting a seat in one of the majors. My applied trombone teacher held one of those seats. My instrument didn't come out of the case for the most valuable lesson he gave me. This was late in my freshman year. I met him at his house (he preferred his home studio to the school's) and instead of going to the studio he took me to his game room in the basement. He asked me what I wanted to do with my performance degree. I said I wanted a seat in one of the major orchestras. He asked me how many jobs I thought there were. I said I thought there were a dozen major orchestras in the US, so maybe 40 or so.

"That would include tenor and bass chairs, right?" he asked.

"Yeah."

"You're a little low. There are 20 or so orchestras that pay a living salary. Call it 80 or so jobs, and 25 to 30 year careers. Two or three jobs open up a year. How many people go on the audition circuit a year?"

"I don't know," I said. "But do the numbers and it has to be 1- 200 coming out of conservatories. Not all will go on the circuit. So, call it 100 a year?"

"More or less. Do you know how I got my job?"

"No."

He told me his predecessor took a sabbatical leave, and he was signed to a one year temporary contract. During the sabbatical, his predecessor announced his retirement. The orchestra signed him to a second one-year contract while they organized the audition. He applied, of course, and as a courtesy (because he was the incumbent) he was advanced to the final round. When the curtain came down, he was one of a few candidates they wanted to play with the section. The other members of the section told the MD and the audition committee, "We've been playing with him for two years. We all know he works in the orchestra. Just hire him." So he was hired.

"I was in the right place, at the right time, and I was prepared. But I got lucky, too. I didn't have to go through the preliminary round. You have the talent. Only you know if you have the drive to fulfill that goal. But you need to understand that the audition circuit is a crapshoot. Orchestras don't cover travel expenses for auditions: you pay for the opportunity to play.

"Think about it."

I did. I had already hedged my bet by continuing to take STEM classes. I changed my major to Biology a week later. I continued to take music classes, and continued lessons. We are coming on 50 years since that lesson. I had a great career as a university professor, and now I have a second career in pharmaceutical research. Oh, and I play in a community wind ensemble, a British style Brass Band, and I had my first rehearsal in the pit for a production of Meredith Wilson's The Music Man today. It isn't the career I envisaged in high school, but if I don't like a conductor, I don't have to play. If I don't like the music, I don't have to play.

There are a few things on my bucket list I haven't gotten to play: Hindemith's Symphonic Metamorphoses is at the top of the list. I have gotten to play some things I didn't expect to play when I changed majors: Sibelius' Seventh Symphony, Saint-Saens Organ Symphony, all the Tchaikovsky Symphonies, etc. I wouldn't change a thing.

The old joke is: What's the hardest thing to do on the guitar? Make money. It's sadly true. Discouraging.