The Death of the Magazine

Or what happens when journalism forgets about quality writing

Magazines are businesses, much like other companies. But there’s one big difference—they almost always get smaller, not bigger.

And I’m not just talking about the number of pages.

For a start, let’s look back at 1960, and make a comparison. Here are the five largest companies on the Fortune 500 back then.

Each of these companies has encountered many problems since 1960—but they all grew significantly. Even if we adjust revenues for the declining value of the dollar, most have outpaced inflation.

Investors who held a portfolio of these stocks enjoyed share price appreciation, and even the worst performing company here (US Steel) paid out enormous dividends to shareholders over the decades.

Now let’s look at the five most popular print magazines in 1960. How do you think they did?

In 1960 the magazines with the most circulation in the US were:

Reader’s Digest (filed for bankruptcy in 2009 and 2013)

Life (regular print editions ended in 2000)

Ladies Home Journal (last print issue in 2016)

Saturday Evening Post (still publishes 6 issues per year, but print circulation is down 95% from its peak)

McCall’s (last print issue in 2002)

You may think that media is a better place to invest than the declining US steel industry or a Detroit carmaker.

After all, magazines in the US don’t have to compete with offerings from China and Germany and Japan. They are always on top of the latest fashion and trends—it’s their business to do that. And they all adapted quickly to the Internet, selling digital ads and taking full advantage of video, audio and other forms of online interactivity.

But none of it worked. The magazine business turned into a death trap for investors.

If you want to support my work, take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

Now let’s compare the magazine business with the movie industry.

Hollywood studios have changed so little that this joke from a 1930 play by Kaufman and Hart can still be understood by audiences today, almost a century later. In this scene a Hollywood gossip columnist admits that the studios gave her a free house in Beverly Hills.

This dialogue ensues:

We still recognize the names Paramount, Fox, Warner, and MGM even after 93 years—because film studios are built to last.

But not magazines.

Even the biggest success stories are vulnerable. I don’t believe there’s a single print magazine right now that’s a sure thing. Even the most popular ones might be gone in another 10-15 years.

That brings us to the subject of the recent layoffs at National Geographic—which lost 13% of its headcount a few days ago.

There have been so many media layoffs recently, that few people paid any attention to this move. Everybody has forgotten about National Geographic.

But they really should pay attention. The rise and fall of the NatGeo brand provides an illuminating case study in how media empires are destroyed.

That’s because, make not mistake about it, National Geographic was once a huge empire—much larger than its current parent company Disney.

Not long ago, 12 million families in the US subscribed to National Geographic, and many held on to every issue. Even in my working class neighborhood, I saw copies displayed on home bookshelves as some kind of iconic repository of the world’s riches.

You didn’t just subscribe, you joined the National Geographic Society—it was almost like being a member of the Explorers Club. As early as 1930, more than one million people in the US alone had joined—and that was during the Great Depression.

There’s a famous joke in the film It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), where George Bailey brags:

“Only us explorers can get it. I’ve been nominated for membership in the National Geographic Society.”

That got a lot of laughs in 1946.

But the magazine did have a special aura. The National Geographic Society financed Robert Peary’s trip to the North Pole, and Richard Byrd’s first flight to the South Pole. Scientists have received 15 thousand grants from the Society over the decades.

The spin-off businesses were enormous, and included everything from maps to jigsaw puzzles. The National Geographic TV specials—which started in 1964—proved especially lucrative, and Elmer Bernstein’s theme song music was almost a clarion call to adventure.

No media company understood brand extension better than National Geographic.

So these popular shows eventually led to a National Geographic cable channel. This was a serious endeavor before Disney took over majority control, and started promoting shows like Sharks Versus Dolphins: Blood Battle.

No print magazine was more ambitious. National Geographic gradually established a business empire as globe-spanning as the explorers it financed. Not even a Great Depression or World Wars could stop it. But National Geographic could not survive the collapse in the magazine business.

Operational control was transferred to Disney in 2019, and this soon turned into another kind of sharks-versus-dolphins bloodbath. In 2022, six editors were fired—the cuts focused on longform journalism, science, and travel.

Those had long been trademarks for the entire brand. But now they were squeezed out in favor of more fast-paced ‘content’ (ugh!).

“Legacy media’s unwillingness to pay for good writing is the single biggest warning sign that its decline is irreversible.“

National Geographic would now focus on “short-form video, specifically via TikTok and Instagram Reels.” The company had no “plan to reduce its monthly print magazine publishing schedule" (or so they claimed at the time)—but more stories would “originate from social videos captured in the field.”

How did that work out?

Not well—at least for the magazine. In June of last year, National Geographic announced that all remaining staff writers had been fired. Stories would now be written entirely by freelancers.

But it won’t be easy to read those stories in print. That’s because US newsstand sales of National Geographic were terminated.

This is an ugly story for anyone who cares about the magazine and its contributions to culture and society. Somehow we went from a smart and widely read periodical that was embedded into a scientific and philanthropic society to a bunch of photos on social media and SharkFest on TV.

That’s depressing—whether you care about money or culture or just plain old geography.

But what happened to National Geographic has happened to many other magazines, and will continue to do so. Consider the case of American Heritage magazine—it was run by Pulitzer Prize-winning historians, and was such a lovingly produced periodical that readers kept and displayed each hardbound(!) copy.

American Heritage did for history and US culture, what National Geographic did for world geography.

But not anymore. Its last print issue came out in 2013.

Even the famous names that survive are almost laughably irrelevant in the culture. Sports Illustrated once featured amazing writers—the magazine even hired Ernest Hemingway (and paid him $15 per word). But who would pick up that rag nowadays with any hope of reading top notch writing?

Time and Newsweek and others have survived on supermarket newsstands, but they look anemic—so much smaller and dumber than they once were. But just consider the writers who once worked for Time, a roster that includes James Agee, Calvin Trillin, Pico Iyer, Robert Hughes, and many other illustrious names.

Nowadays authors at that level would be on Substack, or some other similar platform. That’s because their name would be their personal brand, and they wouldn’t need a periodical—and certainly not a magazine in terminal decline.

And that gets us to the heart of the problem.

In the year 2024, the traditional magazine is rarely the best platform for serious journalism—and that’s true for both print and digital media. The legacy outlets are all chasing short form ‘content’ (ugh!) now, and have lost confidence in good writing.

But here’s the strange thing. Readers are hungry for the longer, smarter writing that these periodicals refuse to publish. As a result, readers increasingly bypass the magazine and deal directly with writers.

That’s the new reality in media. Readers are now more loyal to writers than they are to periodicals. They seek them out. They trust them more. The magazine as an aggregating concept is increasingly irrelevant.

It doesn’t help that pay rates at magazines haven’t kept up with inflation. Not even close.

Legacy media’s unwillingness to pay for good writing is the single biggest warning sign that its decline is irreversible. You might think that National Geographic or Sports Illustrated would try to hire the best talent it could find—that’s the obvious way to turnaround a journalism business.

But they don’t see it that way. They lost confidence in writing years ago.

“Imagine if you owned the Lakers or the Yankees, and put all the emphasis on the team brand—but kept reducing the pay to actual players.”

Back in the mid-1960s, the top magazines frequently paid their best writers a dollar per word. If rates had kept up with inflation, top journalists could get almost ten dollars per word today.

Good luck finding a writing assignment at that rate. The bitter truth is that a dollar per word is still considered attractive in freelance journalism.

A few venerable names still flourish on the newsstand and have maintained high standards—for example, The New Yorker (founded in 1925), The Atlantic (founded in 1857), Harper’s (founded in 1850). I believe that readers are sufficiently loyal to these magazines, and they might survive over the long run.

I note that these outliers still believe in showcasing high quality writing. They haven’t been TikTok-itized (the media equivalent of a lobotomy)—at least not yet. That’s the only reason they have a chance.

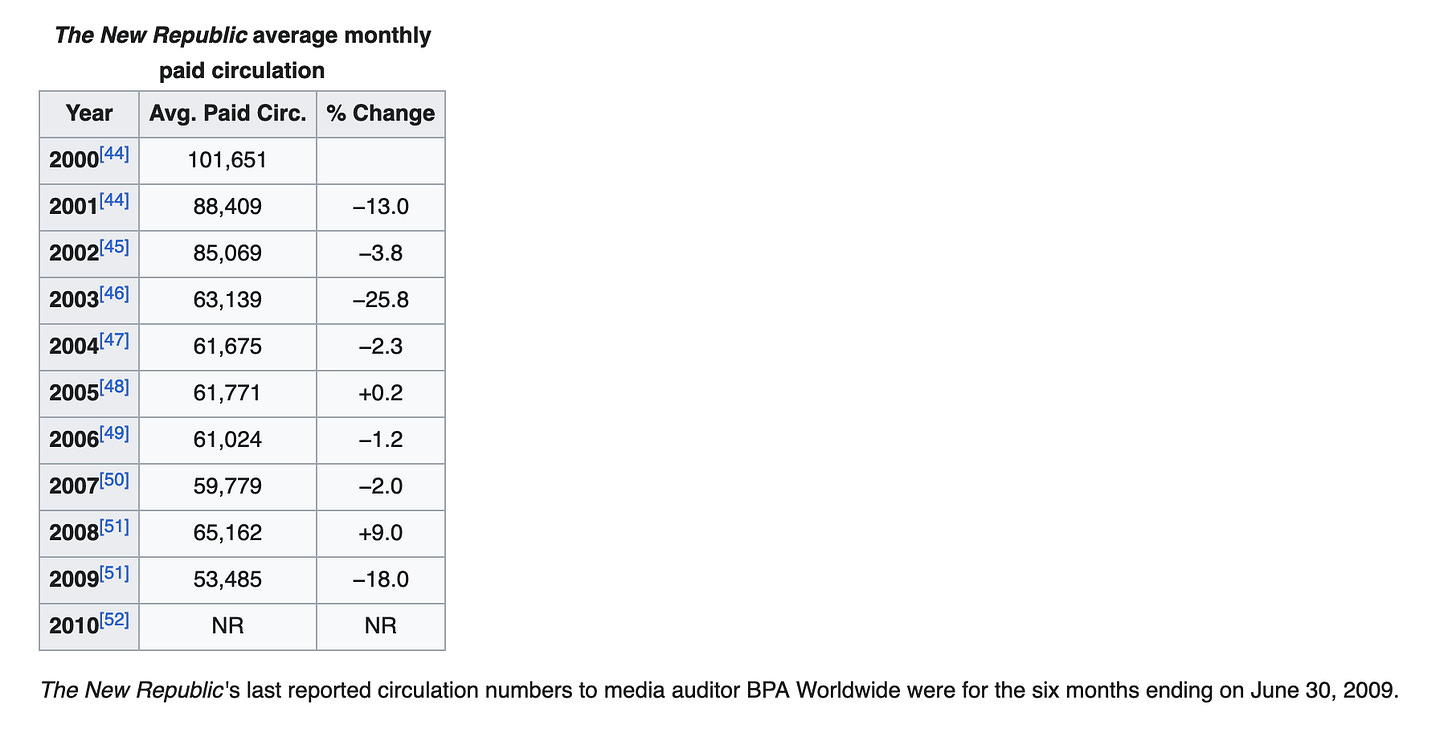

But then I look at what happened at The New Republic, and realize that nobody is immune. That periodical, founded in 1914, had extraordinary influence in its day—people like me read every issue.

But the Internet put the squeeze on print circulation—which fell in half before the magazine stopped reporting the numbers.

Then a super-wealthy technocrat showed up to buy The New Republic. The savior was Chris Hughes, who helped launch Facebook with his college roommate Mark Zuckerberg, and had deep, deep pockets. But even his wealth couldn’t fix the problems.

The New Republic, published weekly for most of its 100-year history, had already cut back to twice monthly. But Hughes made further cuts to just 10 issues per year.

At the same time, the new owner threw a blowout party for the magazine’s centenary, with every power broker in DC in attendance. But it might as well have been a funeral. Just a few days later, an editorial shakeup led to mass resignations.

The magazine never really recovered from that. Hughes gave up on the project, selling out to Win McCormack. The print edition lingers on, but bears little resemblance to the must-read periodical that once featured writing by George Orwell, Virginia Woolf, W. E. B. Du Bois, John Maynard Keynes, Thomas Mann, Edmund Wilson, and other seminal figures.

I focus here on print periodicals, but online magazines aren’t doing any better. The recent calamities at Vice Media and BuzzFeed show how far the once mighty have fallen.

The latest victim is Axios—which could rebrand itself as just Axe, given its latest editorial move three days ago.

Meanwhile, it’s hard to get solid financial information on Salon, Slate, The Daily Beast, and other web media outlets, but none of them retain the reputational luster they once had.

Is there a single web magazine making big bucks?

This is the death of the magazine. There’s no other way to describe it.

But, fortunately, it’s not the death of journalism. Journalism might acutally start growing again. That might already have started happening.

The number of magazines I buy via subscription has declined steadily over the last decade. In fact, I now spend more money subscribing to Substacks than to magazines. Judging by the available data, others are doing the same.

This creates a vicious circle—it’s one of those doom loops I write about:

Magazines lose circulation, so they cut costs and put the squeeze on writers.

The most popular writers leave to launch their own newsletters (or a podcast or some other freelance venture).

This creates further subscription erosion, and the magazine needs to cut costs further.

The whole cycle repeats.

There might be a way to reverse this downward spiral. But the end result would not look like a traditional magazine.

I could envision a range of alternative approaches—all involving bold new ways of hiring and showcasing talented writers. But they all require a mindset and skillset rarely found in the magazine business.

The best role models are from outside of publishing. Sports teams and movie studios are good examples of flexible businesses that have already figured out that audience loyalties are attached to star talent—not business brands. They have learned how to manage that talent, and this alone keeps the larger enterprises healthy and growing.

But old school publishers aren’t thinking in these terms. Instead, they keep shrinking the page count, cutting back on the number of issues, reducing headcount, paying writers and editors less, and looking for gimmicks to increase clicks.

That doesn’t work.

Imagine if you owned the Lakers or the Yankees, and put all the emphasis on the team brand—but kept reducing the pay to actual players. You might continue to sell tickets over the short and even medium term. But to survive over the long haul, you eventually need to support the team brand with commensurate talent at each position—and that talent needs to be nurtured and paid more than peanuts.

Just saying BuzzFeed over and over again isn’t enough. You can even slap the National Geographic name on all sorts of merchandise—but it will still be a dying brand.

Magazine publishers should already know this. But they don’t. And the best they can hope for, if they persist down the current path, is to sell out eventually to a private equity fund—who will manage the endgame with ruthless efficiency.

That’s already happened to much of the newspaper industry.

I’ve seen it repeatedly. When forced to make tough decisions, companies destroy their own selling proposition.

But it’s hard to fix a business by making the product worse. Airlines have gotten away with that—surviving even as they erode service levels—but only because there’s no other comparable option for long distance travel.

Some tech monopolies are doing the same. But you need monopoly power to force inferior quality on an unwilling public.

Magazines aren’t like that. Each time they cut back, they simply accelerate the downward death spiral.

So if you see a newsstand filled with magazines, go and enjoy it now. Because in the future, you will only see something like that in a museum of defunct media.

I’ll mourn their passing. But those who work in journalism can’t waste too many tears on these dinosaurs—these disappearing magazines of the past. That’s because we all need to get to work building something solid to take their place.

Eventually I will have so many paid substack subscriptions that the writers will get together and charge one flat fee for all their writing in one place and thereby reinvent the magazine.

I concur with the entirety of your observations. And I'd like to add another:

The New Yorker and The Atlantic are held up as survivors and paragons. But while I subscribe to both, I am flummoxed by their daily/newsletter offerings. I wish to support thoughtful and observant editorial content - which just doesn't happen when such material is microwaved and not lovingly (and leisurely) prepared. I have the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Philadelphia Inquirer to allegedly provide me with "news" - although they seem to be following each other down the "lifestyle" rabbit hole. What I crave is a curated menu of well-prepared entrees that I can mull over and roll over my intellectual tongue - savoring every morsel. Fat chance.

The world is awash in cleverness; I seek wisdom from people much smarter and more accomplished than myself, who can weave their thoughts into a tapestry of provocative (and well-supported) clarion calls to my noggin. Knee-jerk responses from Remnick, et al really don't pass muster.

Long-form journalism may have left the building (I can recall when The New Yorker regularly had articles that spanned two or three issues). But I'm afraid the headlong rush to "punchy" content has led to a punch-drunk audience. And the cycle will continue to keep on unabated until...well, I'm not sure what turns it around. But the debasement and decline of intellectual property in all of its guises is but a tocsin of the death of a society.