The Day NY Publishing Lost Its Soul

How did we get here? And how do we get back?

Everybody can see there’s a crisis in New York publishing. Even the hot new books feel lukewarm. Writers win the Pulitzer Prize and sell just few hundred copies. The big publishers rely on 50 or 100 proven authors—everything else is just window dressing or the back catalog.

You can tell how stagnant things have become from the lookalike covers. I walk into a bookstore and every title I see is like this.

They must have fired the design team and replaced it with a lazy bot. You get big fonts, random shapes, and garish colors—again and again and again. Every cover looks like it was made with a circus clown’s makeup kit.

My wife is in a book club. If I didn’t know better, I’d think they read the same book every month. It’s those same goofy colors and shapes on every one.

Of course, you can’t judge a book by its cover. But if you read enough new releases, you get the same sense of familiarity from the stories. The publishers keep returning to proven formulas—which they keep flogging long after they’ve stopped working.

And that was a long time ago.

Please support my work by taking out a paid subscription (just $6 per month—or even less if you sign up for a year).

It’s not just publishing. A similar stagnancy has settled in at the big movie studios and record labels. Nobody wants to take a risk—but (as I’ve learned through painful personal experience) that’s often the riskiest move of them all. Live by the formula, and you die by the formula.

How did we end up here?

It’s hard to pick a day when the publishing industry made its deal with the devil. But an anecdote recently shared by Steve Wasserman is as good a place to begin as any.

He’s describing a lunch with his boss at Random House in the fall of 1995. Wasserman is one of the smartest editors I’ve ever met, and possesses both shrewd judgment and impeccable tastes. So he showed up at that lunch with a solid track record.

But it wasn’t good enough. The publishing industry was now learning a new kind of math. Steve’s boss explained the numbers:

Osnos waited until dessert to deliver the bad news…..First printings of ten thousand copies were killing us. It was our obligation to find books that could command first printings of forty, fifty, even sixty thousand copies. Only then could profits be had that were large enough to feed the behemoth — or more precisely, the more refined and compelling tastes — that modern mainstream publishing demanded.

Wasserman countered with infallible logic:

I pointed out, if such a principle were raised to the level of dogma, none of the several books that were then keeping Random House fiscally afloat — Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (eventually spending a record two hundred and sixteen weeks on the bestseller list, and adapted into a film by Clint Eastwood), and Joe Klein’s Primary Colors (published anonymously and made into a movie by Mike Nichols in 1998) — would ever have been acquired. None had been expected to be a bestseller, and each had started out with a ten-thousand copy first printing.

But it was a hopeless cause. And I know because I’ve had similar conversations with editors. And my experience matches Wasserman’s—something changed in the late 1990s.

The old system offered more variety. It took greater risks. It didn’t rely so much on formulas. So it could surprise you.

I lived through the transition. My first editor was part of the old system. He knew that my debut book would only sell a few thousand copies—but he was okay with that. Even before it got published, he asked me to write a second book.

That also sold modestly. But he signed me for my third book—which was a big success. He had patiently nurtured my talent, because he had confidence it would develop. And the system allowed him to do this.

That wouldn’t happen today. Nowadays editors make a commitment to a single book, and it must sell in large quantities. Authors who don’t deliver are dropped faster than a bad Tinder hookup. It’s more like playing the lottery than building a writer’s career.

Back in those simpler days, I was what is called a midlist writer. That meant that I would sell enough copies to make a small profit for the publishing house. But I wasn’t expected to write bestsellers.

But during the 1990s, the midlist disappeared at major publishing houses. I only survived because my third book sold hundreds of thousands of copies. But even I struggled in this new environment. I now had to spend months writing book proposals and pitching projects to editors.

That hadn’t been true with my first editor. He never demanded a proposal. Instead he said: “Just write me a two-page letter describing the book.” That took me a day to do—and I got a contract.

Twenty years later, I was still getting book contracts, but navigating through the system was unbelievably cumbersome. Publishers didn’t want midlist writers anymore, so I needed to convince them that I could sell 50,000 or 100,000 copies (or more).

I somehow managed to survive this transition. But it was painful for me, and tremendously constraining for the culture.

You can’t play a game where everybody is always trying to hit a home run. But that’s the only game New York publishers know how to play today. They’re beefed up and bloated on steroids, aiming for the fences with every swing.

But it’s not working—literary culture can’t survive in a world of risk avoidance, stale formulas, and clownish covers.

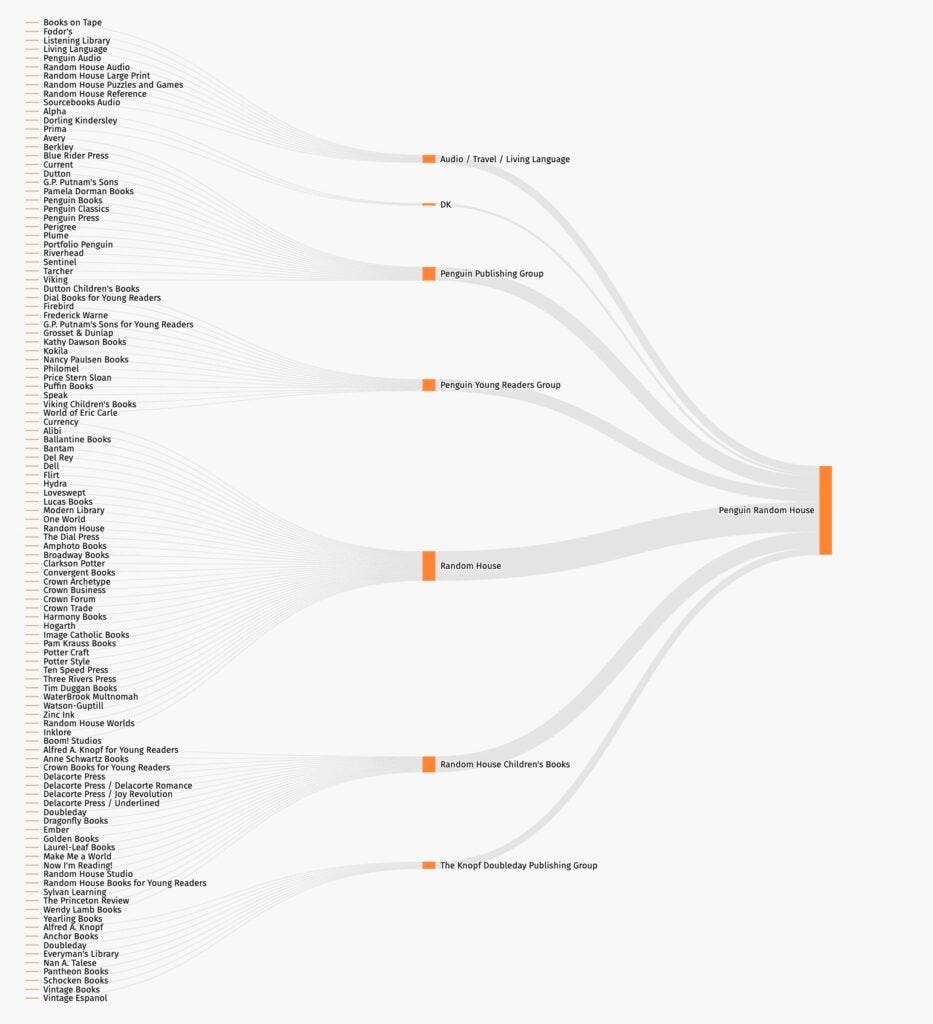

The death of the midlist didn’t happen by chance. It took place because of tremendous consolidation. Let’s consult Wasserman again:

One example tells the larger story: Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer founded Random House in 1927 and bought Alfred A. Knopf in 1960 and Pantheon the following year. Four years later, in 1965, they sold it to RCA and then RCA, in turn, sold it in 1980 to Si Newhouse’s privately owned Advance Publications for between $65 million and $70 million in cash. Newhouse ruled the roost for eighteen years and then sold in 1998 to the private German multinational conglomerate Bertelsmann, which paid a reported $1 billion, making Bertelsmann a publishing Goliath.

Here’s a chart that show you how crazy this consolidation has been. This is just the stratification at Penguin/Random House. (You can see the breakdown for all of the major publishers at this link.)

You can’t understand the stagnancy of publishing today without understanding this history. When Random House was a tiny independent company, it could make a tidy profit by publishing books that sold just ten thousand copies. But when you’re part of a billion dollar corporation, those books don’t move the needle—you need something bigger and splashier.

So you put large fonts on the cover, along with fancy shapes and garish colors. And the story inside those covers has to be tried and true.

You are now imprisoned by the formula.

The problem starts at the top. I can’t find out how much the CEO of Bertelsmann makes, but I do know that his compensation at his previous job was $1.7 million. So I assume he’s making at least as much at his new job.

This is great for him—but terrible for the book business. You can’t pay enormous salaries like this by publishing smart and bold midlist books. You’re not allowed to take risks. So editors have to reach for surefire books—celebrity memoirs filled with juicy gossip, formula novels with the potential for a Netflix adaptation, self-help books from Instagram influencers, and other dumbed down mass market fare.

If it works, the CEO gets that huge payday. But the literary culture goes down the tank—which is where we’re sitting right now.

We don’t need to accept this.

We can have a healthier, more robust book culture—but it won’t happen inside the intensely consolidated world of the Big Five publishers. We need fresh air.

Here’s the problem: Those Big Five control over 80% of the trade publishing market. Indie publishers exist, but they need more support—a lot more support—than they’re getting.

There are so many obstacles:

For a start, we need newspapers that review indie books. But newspapers have also disappeared—because of the same forces of consolidation.

We need indie bookstores that support books outside of the Big Five. But indie bookstores have struggled too, and many have shut down.

We need schools and colleges that educate the next generation of readers. But many professors have stopped assigning entire books—in a misguided attempt to adapt to digital swipe-and-scroll culture.

So we are at our last line of defense.

We still have individual readers who will seek out more challenging or provocative literature.

We still have book clubs that operate outside of the influence of the dominant hierarchies of consolidation.

We still have public libraries that aim to serve their communities.

We still have indie critics (many of them on Substack), as well as a few platforms where they can reach an audience.

And we still have a few renegades working inside the system—at schools, publishing houses, media outlets, etc.—who bravely resist the dumbing down. God bless ‘em.

I make a point of supporting these independent voices. I encourage you to do the same.

Don’t think for one second that we don’t need independent writers. The forces of conformity and centralization of power are stronger now than ever. Books have always been our safeguard in such troubled times. But when books are controlled and constrained by the entrenched system, they fail to provide us with meaningful alternatives.

Our safety and freedom only come from indie culture, alt culture, counterculture.

I don’t think we can fix the legacy players who created this mess. But we have a decent chance of building something outside their control. And if we make headway with books, we might just do the same for movies and music and all the rest.

Local indie bookstores play a crucial role for new authors. I was turned down by local publishers, so I self-published my first novel. A local independent bookstore let me stock some copies and allowed me to hold a reading. I read an excerpt, played some music. The result was my book was a summer best seller at their stores. One of the clerks told me I had more people there than some signed authors do. This success wouldn't have happened without the help of this independent bookstore.

Just loafing around college in the mid-70s I read One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Catch 22, Sometimes a Great Notion, A Clockwork Orange, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance...and multiple books by Hunter Thompson, Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, and Walker Percy. All these were powerful influences on the culture at large, contemporary writers writing about contemporary issues and concerns. You would go to parties and people will talk about books as much as they did music. I feel sorry for those who missed it. Nothing like that exists now.