The Best and Worst Hit Songs of the 1960s

Spicy opinions from Chris Dalla Riva's new book 'Uncharted Territory'

Chris Dalla Riva is a guru of data analytics on popular culture. He’s been a longtime friend to The Honest Broker, and I’ve learned a lot from his work.

And now Chris has released a fun and fascinating book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. This is the closest music writing gets to the freewheeling conversations ardent fans have among themselves about bands, songs, and rising or falling reputations.

But Uncharted Territory also draws on the scrupulous research that is Chris’s trademark. (You might have seen some of it on his Substack Can’t Get Much Higher.)

With his permission, I’m sharing an extract below on #1 hit songs of the 1960s. The entire book deserves your attention. You can learn more at this link.

Please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

From UNCHARTED TERRITORY

By Chris Dalla Riva

When I decided that I was going to listen to every song to ever get to number one on the Billboard Hot 100, I wasn’t in a great spot. My mental health was suffering greatly, and I was working a job that I hated. Every waking moment outside of my job was spent with my guitar. Some nights I would literally fall asleep playing. Still, I did not feel good. And nothing seemed to help. Therapy. Medications. Exercise. Socializing. It was all a wash.

For some reason, I decided that a musical quest might help. I set out to listen to every number one hit since the Hot 100 was started in August 1958. Why? Again, I was a musician. I thought it might help my songwriting. Maybe I could unlock some secret to writing a hit and use the knowledge to quit my job. At the same time, I thought it might be good for my sanity. I would only listen to one song a day. Listening to one song a day is an easy thing to accomplish. Maybe one little win could right my mind.

And it kind of did. A friend soon joined me on my journey. Each day, I would text him the number one hit. We’d both listen a few times. I’d play along on my guitar. We’d talk about it and rate the song out of ten. I started tracking those ratings in a spreadsheet. Slowly, that spreadsheet began to balloon as I tracked a ton of other facts and figures. Trends began to emerge, and I started to write about them. My musings became Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music that I wrote as I spent all those years listening to every number one song.

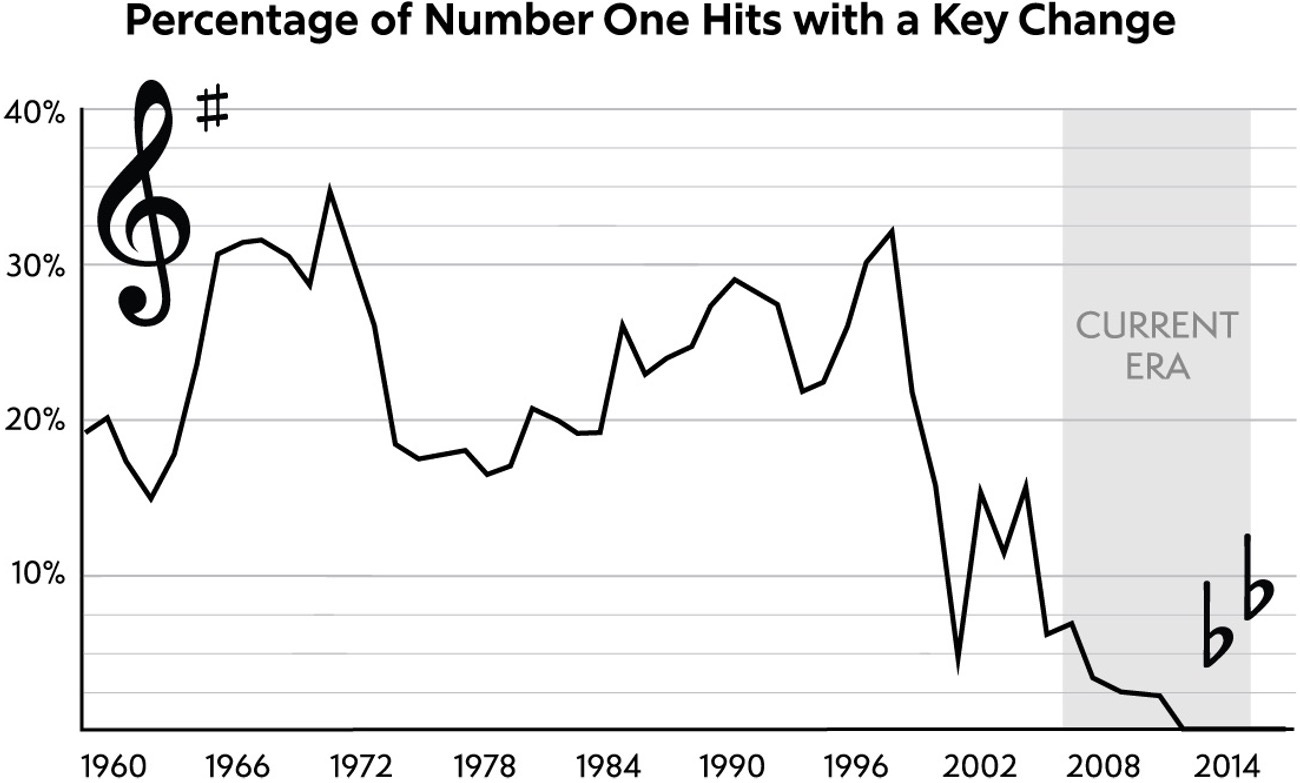

While this book is packed with charts, graphs, and tables designed by my friend Caileigh Nerney (see an example above), I still wanted to keep songs at the center of my journey. In fact, at the end of each chapter, I highlight the best and worst number one hits of each era as determined by myself and various friends and critics. Below we highlight those songs from the first three chapters of the book, sorted chronologically by when they hit number one. While you may not agree with all of my takes on these songs—that’s fine, I intend them more as conversation starters than conversation enders—I think you will agree that it’s important for us to be able to articulate how we feel about art.

NUMBER ONE HIT SONGS FROM THE 1960S

HIGHLIGHTS

“Georgia on My Mind” by Ray Charles (November 14, 1960)—The reason this song has been recorded hundreds of times is because the melody sounds like it was delivered from the high heavens. That’s not a shock. That melody was written by Hoagy Carmichael, the man behind classics like “Stardust” and “Heart and Soul.” But the reason you know this version of “Georgia on My Mind” rather than any other comes down to a different person: Ray Charles.

To state the obvious, Ray Charles was a talented piano player. You can hear that talent shine on the jazzy fills he sprinkles throughout this song. But his greatest instrument was his voice, a voice whose subtle slides and slurs could make Georgia feel like your home even if you’d never been within a thousand miles of it.

“Runaway” by Del Shannon (April 24, 1961)—Allegedly when Del Shannon recorded this song, he was so nervous that he sang flat. It was up to producer Harry Balk to speed the tape up to get the vocal in the right key. But I can understand why Del Shannon was nervous. From the fuzzy guitar to the cascading piano and the twisting proto-synth, “Runaway” makes a breakup feel like the end of the world. And if you are to properly capture the romantic apocalypse of the lyric “Tears are falling and I feel the pain / Wishing you were here by me / To end this misery,” you probably shouldn’t be able to control your nerves.

“Running Scared” by Roy Orbison (June 5, 1961)—Roy Orbison is filled with fear at the beginning of this song. “Just running scared each place we go / So afraid that he might show,” he sings over a lone acoustic guitar. Though he repeats the fearful title at the top of each of the first four verses, there’s also a fire burning within him. And that fire grows stronger as new production elements emerge section by section. First, it’s percussion. Then strings. Then wistful back-up vocals. When the song reaches its climax, Orbison’s voice is quavering over a full band. “My heart was breaking, which one would it be?” he bellows. “You turned around and walked away with me.” As the song fades, someone is running scared. But it’s not Roy Orbison.

“He’s a Rebel” by The Crystals (November 3, 1962)—The music industry has been filled with shady characters since its inception. “He’s a Rebel” is a good example of this because, despite what every copy of the record says, it’s not actually by The Crystals. The Crystals were on tour when Phil Spector decided that he wanted to record the song. So, he brought in a different group called The Blossoms to do it. The Crystals had no idea until they heard it on the radio. Because of a questionable contract, Spector was able to use their name without their consent.

Even through all that trickery and deception, there’s no denying that “He’s a Rebel” is a musical achievement. When the song opens, it sounds thin, a circular piano riff barely twinkling over some drums. But somehow when you get to the chorus, the song is humongous, sax-wailing, and voices swirling. I’ve listened to this song countless times, and I’m still not sure how Spector and “The Crystals” were able to pull it off.

“My Girl” by The Temptations (March 6, 1965)—When Smokey Robinson wrote “My Guy” for Mary Wells, I imagine he thought he’d never write a better song. “My Guy” is just so expertly crafted that burgeoning songwriters should study it. But then a year later, he decided to write a response to “My Guy” for The Temptations. Response songs were very common during the 1960s. Chubby Checker hits it big with “The Twist.” Joey Dee jumps on the bandwagon with the “Peppermint Twist.” Only one name made sense for Smokey’s response: “My Girl.”

“My Girl” is not just the greatest response song of all time, it might be the greatest song period. I’d go so far as to argue that if a random DJ in the twenty-first century cut off whatever booty-shaking track they were playing at the club on Friday night and put on “My Girl,” nobody would complain. Decades later, the ascending guitar riff and finger-snapping rhythm that drive this track remain as fresh as ever.

“Ticket to Ride” by The Beatles (May 22, 1965)—The Beatles’ most miraculous skill might be how they could smash together disparate styles. That skill is on full display in “Ticket to Ride.” The verses are a jangling pop song with a droning guitar note throughout, reminiscent of an Indian raga. The bridge is strait-laced rock ‘n’ roll. The outro is a country and western hootenanny with a looping, falsetto vocal. You wouldn’t notice these stylistic differences without paying close attention, though. The Fab Four make them sound like they’ve always gone together.

“You Keep Me Hangin’ On” by The Supremes (November 19, 1966)—Even if there were no vocals on this track, you’d feel the uncertainty. The key shifts back and forth between sections. The guitar riff sounds like a telegraph signal that you can’t decode. And it might be. Because at the beginning of this song, Diana Ross can’t make sense of anything. “Set me free, why don’t you, babe?” she pleads with her lover. Though anxiety persists throughout, her questions turn to demands at the end: “Go on, get out, get out of my life.” Sometimes you need to take matters into your own hands.

“(Sittin’ On) The Dock of The Bay” by Otis Redding (March 16, 1968)—Topping the charts in the wake of Redding’s death, this is a record that can trick you. The rise and fall of the melody, the nautical sound effects, and the whistling all capture a tranquil day by the water. But that’s only part of the story. Listening to the lyrics and Redding’s delicate delivery, we see a lost narrator. Part of the reason he is “wasting time” on the dock of the bay is because he has nowhere else to go and wants to forget it. No matter how many miles you roam, certain things are inescapable.

“I Heard It Through the Grapevine” by Marvin Gaye (December 14, 1968)—This song is about humiliating heartache. It’s about finding out your lover is done with you indirectly, through rumors circulating on the streets, rumors you are the last to be privy to.

That rumor starts with the keyboard playing a circular riff in its lower register. Then it moves to the drums, a soft thump, your heartbeat. Then it finds its way to the guitar and strings echoing the initial whisper of the keyboard. With each step, the truth becomes more apparent. Then Marvin Gaye arrives, the pain dripping from his voice, a voice whose range and control are nearly inhuman. He knows the truth, and even if “a man ain’t supposed to cry,” he can’t hide his pain.

LOWLIGHTS

“The Battle of New Orleans” by Johnny Horton (June 1, 1960)—Jimmy Driftwood, an Arkansan educator, wrote this song to pique his students’ interest in American history. It must have worked. The composition went on to win Song of the Year at the Grammys in 1960 after being popularized by Johnny Horton. As some of President Andrew Jackson’s exploits have become widely recognized as horrific (e.g., Indian Removal Act), hearing about his military triumphs set to a rollicking banjo isn’t something your average person would voluntarily subject themselves to.

“Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini” by Brian Hyland (August 8, 1960)—This song is about a girl who is embarrassed by the yellow polka dot bikini she is wearing and runs from place to place to stay covered up. She starts in a changing room, then runs to a blanket, and then into the water. While in the water, she’s described as “turning blue” before the final line declares that there isn’t anywhere else for her to go. Call me crazy, but I think this irritating song might have a sinister, deathly undertone that everyone else has missed. And even if I’m imagining it, it still makes me feel sick.

“Moody River” by Pat Boone (June 19, 1961)—Written about a girl who drowns herself out of shame for her infidelity, “Moody River” fits squarely within the teenage tragedy tradition. Sort of. The lyrics of “Moody River” do tell of a tragedy, but the music does not. The arrangement is built around a piano that lives at the intersection of cheery and jangly. There is no law dictating that music and lyrics align, but having those two things at odds in this song makes the narrator sound more like a sociopath than a high schooler experiencing unspeakable trauma.

“Wooden Heart” by Joe Dowell (August 28, 1961)—This song is a cover of a waltzing German tune that Elvis Presley took to the top of the British charts. I guess the thought process was that if it were a hit for Elvis in the United Kingdom, then somebody in the United States needed to record it. That somebody turned out to be Joe Dowell. While Dowell’s voice is bland, “Wooden Heart” isn’t helping him out. It’s built around a keyboard that might have the honor of being the most annoying recorded sound in the twentieth century.

“Go Away Little Girl” by Steve Lawrence (January 12, 1963)—My sister Natalie was walking through the room while I was listening to this song. 27-year-old Steve Lawrence crooning the words “Go away, little girl / I’m not supposed to be alone with you” stopped her dead in her tracks. “Is this by a pedophile?” she asked.

Despite how creepy that couplet might sound, the lyrics are not anything criminal. The song was composed by Carole King and Gerry Goffin about a man tempted to cheat on his lover. Albeit patronizing, the term “little girl” was common fare in pop songs at the time. In this era alone, it’s used in five additional songs, including The Beatles’ “I Feel Fine” (e.g., “I’m so glad that she’s my little girl”) and Tommy Roe’s “Sheila” (e.g., “Man this little girl is fine”). But when you need this many words to explain why a creepy-sounding song actually isn’t creepy, you’re probably not going to have people lining up to listen to it.

“Mrs. Brown, You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter” by Herman’s Hermits (May 1, 1965)—While the palm-muted guitar on this track does create some interesting texture, any interest you might have in that texture is destroyed by a painfully plain vocal singing about how “it ain’t no good to pine” for a girl like Mrs. Brown’s daughter.

“The Ballad of the Green Berets” by SSgt. Barry Sadler (March 5, 1966)—When looking back at the 1960s, we often remember the scores of artists who wrote songs in protest of the Vietnam War. But there really were people who supported it. “The Ballad of the Green Berets” is proof of that. Topping the charts for five weeks on its way to becoming the tenth best-selling single of 1966, SSgt. Barry Sadler’s military march is an unabashed celebration of the armed forces, the soldier in his song dying with only one final request for his wife, namely that their son also serve. Now knowing about the endless, pointless destruction of the Vietnam War, this musical wish is hard to stomach.

“Honey” by Bobby Goldsboro (April 13, 1968)—Telling the story of a man whose wife died, “Honey” falls within the maudlin tragedy song tradition. But what makes this sappy song stand out is that it’s not clear whether the narrator ever really liked his wife. He describes her as “Kind of dumb and kind of smart,” while also recounting how he laughed himself to tears when she almost hurt herself falling in the snow. With lines like, “She wrecked the car and she was sad / And so afraid that I’d be mad, but what the heck,” the only thing you should feel after “Honey” is hope that you’ll never be in a relationship like this.

“In the Year 2525 (Exordium & Terminus)” by Zagar and Evans (July 12, 1969)—In Dave Barry’s novel Tricky Business, he describes a band that is forced to work the party circuit after they fail to make it big. When the group is asked to play a song that they don’t like, Barry describes how they then perform a retaliation song to punish the audience. “In the Year 2525” is described as the “hydrogen bomb” of retaliation songs. While I don’t know if I’d go that far, it’s a strange song that predicts the future in thousand-year increments. If Zager and Evans are correct, then in the year 4545 you’ll no longer need your teeth because “You won’t find a thing to chew.” Dentists, please beware!

You can share your own picks for best and worst hit songs from the 1960s in the comments. Learn more about Chris Dalla Riva’s Uncharted Territory at this link.

And in the spirit of "Go Away Little Girl," I give you "Young Girl" by Gary Puckett & The Union Gap. It only made it to #2 on Billboard (somehow "Number 2" seems appropriate here) so I guess it was out of contention for this list. But it made MY Spotify playlist called "Songs for Stalkers & Other Pervs" (originally named "Songs for Rapists, Pedophiles, Stalkers & Other Pervs." Spotify made me change it a few years ago.) https://open.spotify.com/playlist/1nxTPVd2pjLsgelCLhab7G?si=79ec19a9643544ed

If I'm being honest, I enjoy the alleged lowlights far more than the songs listed as highlights.