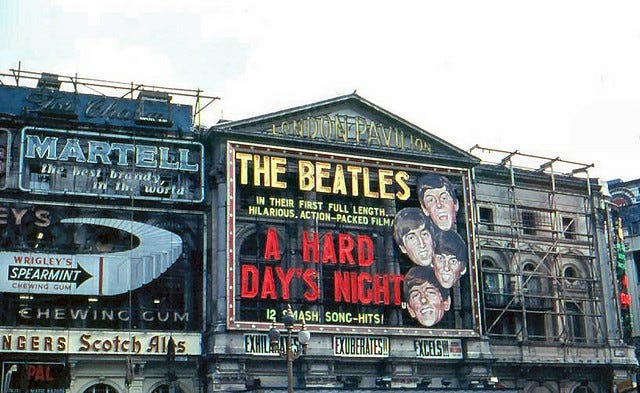

The Beatles as Comedians

They might have been the Marx Brothers of the Age of Aquarius

In 1964, the Beatles were the most popular music act in the world—but who knew how long it would last? Mop-top boy bands from Liverpool might just be a passing fad, like hula hoops and lava lamps.

So the band got rejected by producer Nat Cohen when they approached him about financing a Beatles movie. He was unimpressed, and moved on to other projects (including Percy —a film about a penis transplant).

As the Romans said, there is no accounting for taste. But United Artists saved the day, agreeing to make a low-budget Beatles movie—although they did it mostly to get rights to a soundtrack album.

“What we lose on the film we’ll get back on this disc,” admitted a United Artists exec. And they planned to make this movie fast and cheap.

Please support The Honest Broker by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

The budget was just £200,000, and the filming only took seven weeks. The goal was to exploit the Beatles’ popularity while it lasted. So everything was rushed—John Lennon wrote the title song in one (hard day’s) night, and the band recorded it in just three hours (although musicologists still argue over the opening chord).

But the studio met their deadlines, starting production in March 1964 and somehow getting the movie into theaters in early July.

The response was unprecedented—so many cinemas wanted A Hard Day’s Night, that 1,600 prints were in circulation at the same time. The film generated $14 million in its initial release.

Beatles fans loved it—of course they did. But so did critics. In the Village Voice poll that year, A Hard Day’s Night finished second, only falling behind Dr. Strangelove. Time magazine later picked it as one of the 100 best films ever made.

Somehow, against all odds, these four young musicians, lacking any film experience, had managed to make one of the greatest comedies of all time.

Some critics even compared the Beatles to the Marx Brothers—one of the finest comedy ensembles in cinema history. It’s actually quite an apt comparison.

John Lennon’s demeanor and verbal humor definitely reminds me of Groucho Marx. And Ringo is a court jester in the style of Harpo Marx. Paul and George both show a knack for deadpan humor. You can call it a cross between Chico and Zeppo Marx.

You can’t deny it—in aggregate, they are a stunningly good comedy team. And they were all amateurs.

This had never happened before.

When they turned Elvis into a film star, they cast him as a romantic lead in a war movie. When Frank Sinatra finally established himself as a legit movie star, it was in another war movie. In many other films of that era, musicians had almost no acting responsibilities in the their movie appearances—they just got a few minutes on screen to perform a song.

But the Beatles aimed much higher—even on their tight budget and production deadline. They not only went for laughs, but did so in their own mordant postmodern way. At some moments, you might be fooled into thinking that Beckett or Ionesco had written some of their lines.

So give director Richard Lester and screenwriter Alun Owen credit for seeing comedic potential in these four musicians. But you also need to give the Beatles credit—because they chose Lester and Owen.

Lester had deep roots in comedy and music. He had worked with Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan on three TV series in the 1950s. But John Lennon had been especially impressed by Lester’s The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film, an Oscar-nominated short movie that the director had made for just seventy pounds—filming it over the course of two Sundays in 1959.

It’s a shame that Lester only had the chance to make two Beatles movies—A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and the followup Help! (1965). The band had too many other opportunities and commitments. And filmmaking was tough—especially the more tightly scripted Help!

John Lennon later recalled:

I realize, looking back, how advanced it was. It was a precursor to the Batman “Pow! Wow!” on TV – that kind of stuff. But [Lester] never explained it to us. Partly, maybe, because we hadn’t spent a lot of time together between A Hard Day’s Night and Help!, and partly because we were smoking marijuana for breakfast during that period. Nobody could communicate with us.

But even if the Beatles walked away from this opportunity, others rushed in to take their place. In 1966, The Monkees TV series followed an almost identical formula—mixing Beatles-esque pop with madcap humor. The Batman series from that same year was even more popular, turning the classic superhero story into campy and surreal comedy, where even fight scenes were played for laughs.

But the most lasting impact of the Lester/Beatles collaboration can be seen in the later rise of the music video as a quasi-narrative way for launching pop songs. In the early 1960s, filmed musical performances were on TV every night, but nobody was doing it like Richard Lester and his four young collaborators.

There are so many lovely touches in these films. I especially like the Beatles’ apartment in Help!—which is like a cross between an out-of-control mancave and Pee-wee’s Playhouse. Or the scene in the Indian restaurant where the house band plays a Hindustani version of “A Hard Day’s Night” in the background. And, of course, the recurring chase scenes, which capture a sweet slapstick craziness.

The screaming female fans who constantly chase the lads from Liverpool is straight out of Buster Keaton’s Seven Chances from 1925. But when the Beatles aren’t running away from ladies, they are pursued by police or sacrificial cults. Sometimes it seems like half of the running time of these films is actual running.

The Beatles were a natural at all this. So even if they stopped making comedy films with Lester, they never abandoned comedy. Lester did manage to convince John Lennon to join the cast of How I Won the War (1967), where a Beatle (finally!) plays a soldier, but radiating lots of dark humor in a Catch 22 kind of way.

But this would be Lennon’s only appearance in a non-musical film. In the future, he would save his Groucho Marx-style ironic quips for TV interviews and song lyrics.

Ringo, a natural comedian, had the most ambitious career in films, even while still a member of the Beatles. He appears in Candy (1968) and The Magic Christian (1969)—both based on campy Terry Southern novels. The latter was filmed in the same studio where the Let It Be project started—and almost at the same moment.

He occasionally got drawn back into film projects (perhaps most notably as narrator for Thomas the Tank Engine). But he never really took the plunge into a full blown movie career, and I’m left disappointed that he didn’t do more on screen.

The Beatles, as an ensemble, also leave me wanting more from their comedic talents. But, to their credit, they still retained their sense of humor, even after ending their partnership with Lester. It shows up in their animated feature Yellow Submarine (1968), their TV film Magical Mystery Tour (1967), and even in the film footage for Let It Be, from the very end of their collaborative career.

When almost eight hours of that material finally got released in 2021 as The Beatles: Get Back, the public could see how playful and comic these musicians were right before their breakup. They spend hours clowning around, making faces, doing parodies, and goofing off.

Sometimes this showed up in their songs. But a lot of it happened in-between takes and during rehearsals. I can’t help concluding that each of these four music superstars had an alter ego comedian inside just waiting for a chance to come out.

In a final epilogue, George Harrison struck up a friendship with comedian Eric Idle, who convinced the former Beatle to finance the Monty Python film Life of Brian, after EMI backed out. Harrison wrote a check for three million pounds—allegedly because he wanted to see the movie. John Cleese later joked that Harrison purchased the most expensive movie ticket of all time.

But it proved to be a shrewd investment. The film made $20 million at the box office. But Harrison also got a cameo appearance.

Those few seconds in front of the camera are almost a symbolic statement of the Beatles’ elusive relationship with the comedy world. Those lads had such talent—and not just as musicians. And for a while it seemed like they would be joking with us forever.

But it was gone in a flash, a historic movie career squeezed into just a few hectic months. You can see both A Hard Day’s Night and Help! in three hours. If you haven’t done so, find a way to do it. It’s time well spent from your hard day (or night).

Let's not forget the 1966 and 1967 Xmas records, very Goonish, "You Know My Name (Look Up the Number), and the Immortal "Rutles", which would not have happened without the involvement of George Harrison. He supplied the work-in-progress Beatles Documentary to screenwriter and active participant Eric Idle—Dirk McQuickly and narrator for the mockumentary—and also had a very deadpan cameo in "All You Need is Cash" as a BBC-ish TV reporter, noting the collapse of "Rutlecorps". George also was on Idle's "Rutland Weekend", on board to sing "My Sweet Lord" but really wanting to be a pirate. Richard Lester said that, of the four, Harrison was the one with a true comic bent.

George Martin saw their comic potential and signed them to EMI largely because of it. One of them quipped in an interview many years later that “everyone from Liverpool is a comedian”.