The Bands Are Never Coming Back

The era of group collectives dominating the charts has ended, probably forever—and it's an issue much larger than just music

I recently did a count on the Billboard Hot 100, but I already knew what it would show. Fewer than 5% of current hits are by bands. Even when the name sounds like a group—meet The Weeknd, my friends—it’s really an individual.

There were actually more hit songs by people who have adopted band names than genuine bands on the list.

What is that all about?

Here’s a quiz—which of these are bands, and which are individuals?

Tank

deadmau5

Juice Wrld

Cat Power

Grimes

Lost Frequencies

Bad Bunny

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

If you correctly identified all of these as individuals, I commend you. You scored 100%. On the other hand, you may want to consider getting a life.

Tomorrow’s quiz will be: EDM producer or account password?

Baby boomers are puzzled by this state of affairs. If you take the Summer of Love—that’s 1967 for those puzzled by the label—as a baseline, the music world was all about ensembles and partnerships. Revisiting the songs in rotation on the most popular radio station in LA from that period (KHJ), I found that only one-third of the songs came from individual artists.

I must immediately add: The Summer of Love wasn’t typical, and any comparisons of other eras with the glory years of rock music are highly misleading. The push for collectives and cooperatives reached a peak in the 1960s, but it was an anomaly. I doubt I will ever see another period when commercial music will be so focused on group identities.

Many art forms—novels, poetry, etc.—have never experienced a genuine era of cooperative creativity. Great artists are rarely team players, no matter what their field of endeavor.

“Bach and Handel were born within a few days of each other, and might have made a great partnership—a Baroque equivalent of Lennon and McCartney—but it would never have happened, even if they had lived on the same street.”

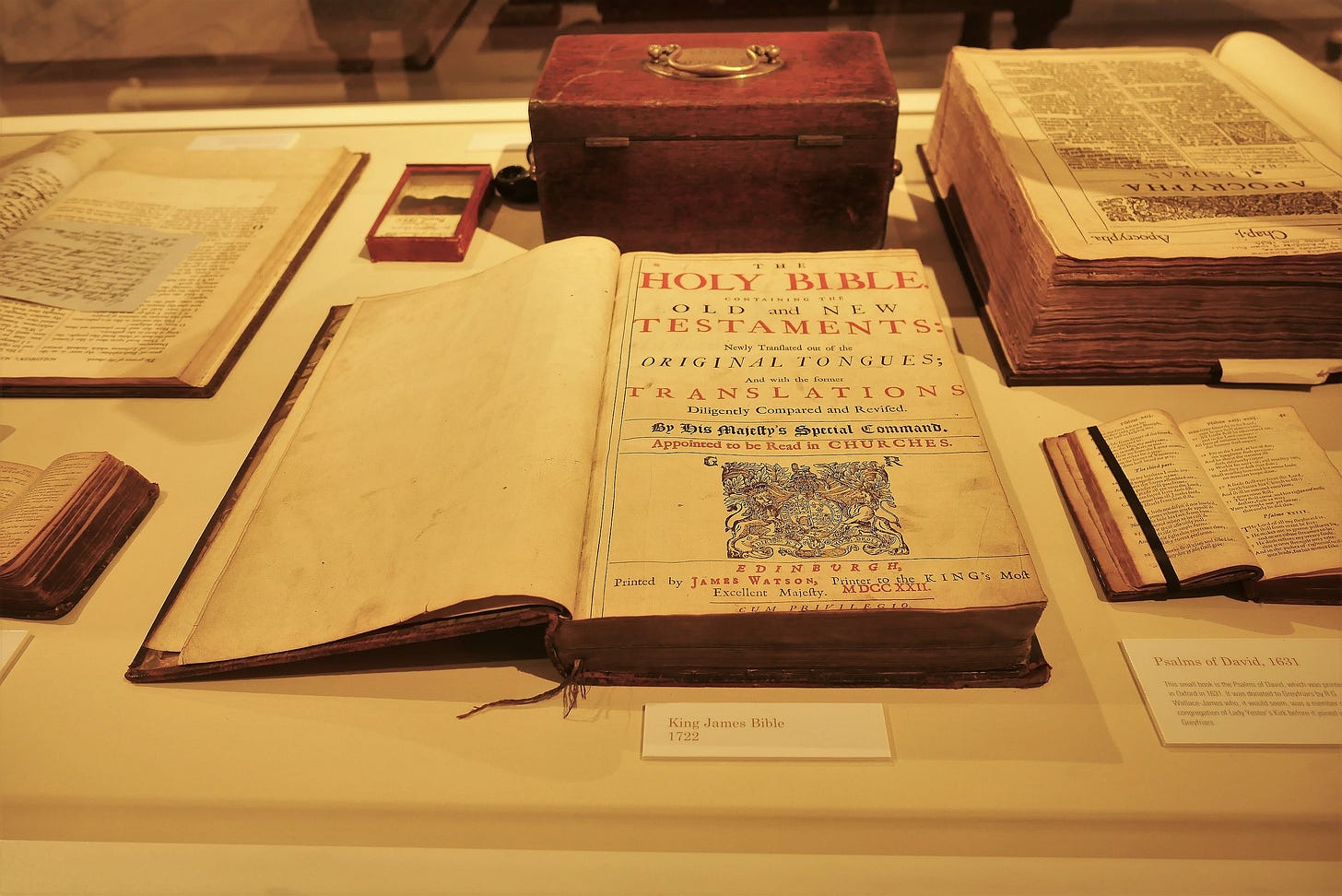

“No great work of literature was ever created by a committee,” according to a pessimistic adage. Some dissenters will point to the King James Version of the Bible, created by a group of 47 translators working on 6 committees between 1604 and 1611. That’s certainly the most often quoted work in the English language, and it was a team effort from first to last.

Yet others insist that this is truly the exception that proves the rule: the only time a committee ever created an influential literary work in English, they argue, was when divine intervention protected the “Word of God.”

I’ve sat on other committees that could have used a little help from above, and it never arrived.

I prefer not to dig into the question of literary collaborations—which would get me into endless squabbles about whether the great epic poet Homer was actually a group of individuals, etc. etc. I will simply point out that the rise of collective creativity in music is a very strange thing, and that nothing we encounter in other idioms prepares us for the prominence of groups during the last seventy years.

That period is now coming to an end, and we are returning to the mindset of the 1940s. Back then almost every successful band was built on the identity of a famous bandleader. With very few exceptions (The Ink Spots, the Casa Loma Orchestra, etc.), the hits got assigned to individuals. Even when Benny Goodman or Glenn Miller or Artie Shaw relied on outside composers, arrangers, and soloists, their name went on the recordings and posters. Duke Ellington, for all his considerable ability, didn’t write all the music associated with his band—but how many fans even knew the name Billy Strayhorn back then? Or that a host of other Ellington hits were either composed by (or borrowed from) other members of the band?

If you look at the hit songs from 1940s, the situation is very similar to today. Around 95% of them are attributed to individuals, even when musicians in the band and behind-the-scenes did much of the heavy lifting.

And if you go further back in time, the situation is even more marked. Haydn could have collaborated with Mozart, but never considered it. Bach and Handel were born within a few days of each other, and might have made a great partnership—a Baroque equivalent of Lennon and McCartney—but it would never have happened, even if they had lived on the same street.

Great composers, like unruly preschool children, don’t play nicely with others.

Why did this change with the arrival of rock music? Rock is a very individualistic form of expression, so you might think that ensembles operating under a collective name would be rarities. But the exact opposite happened, especially in the 1960s.

What was the cause?

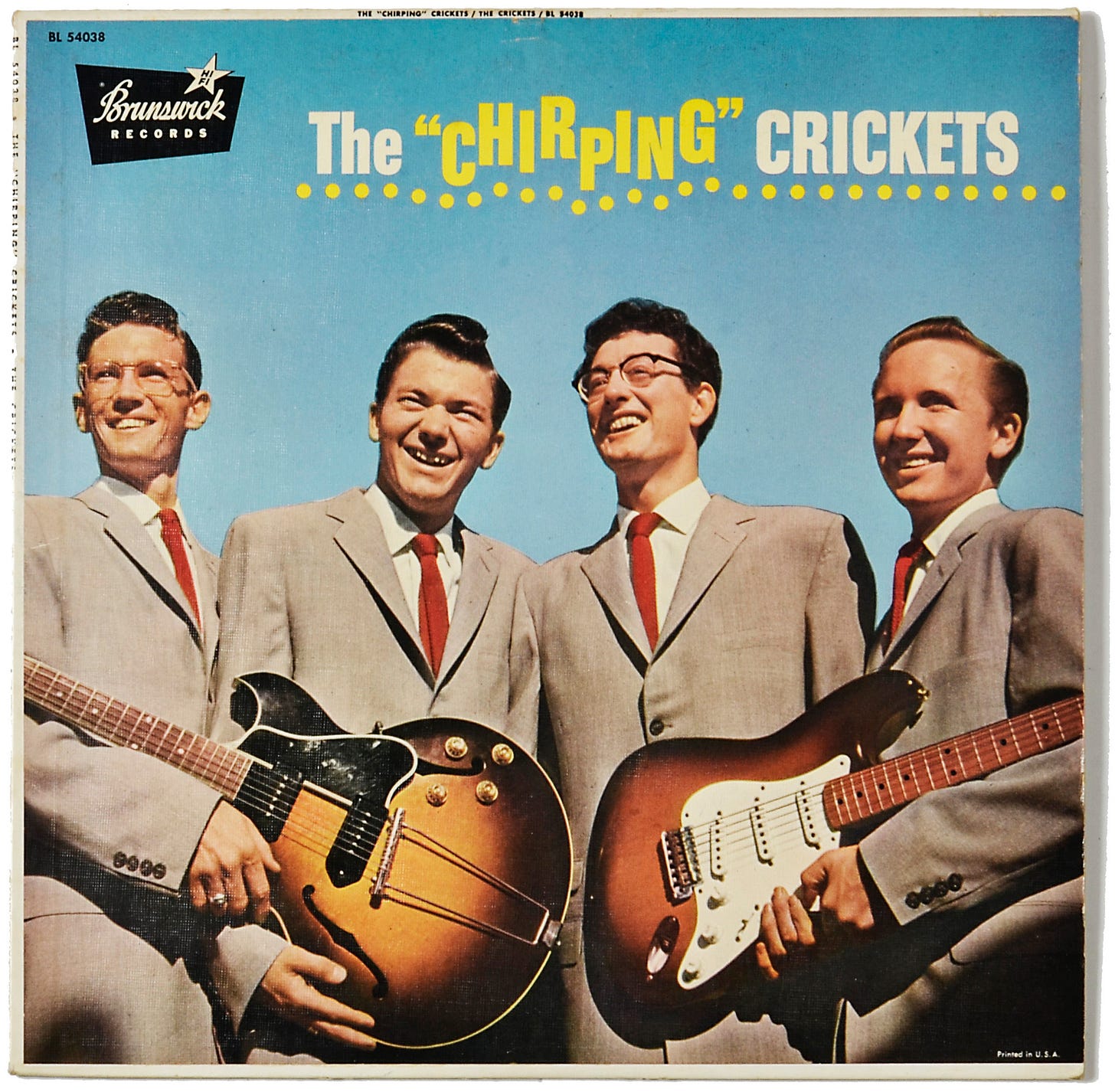

Clearly the Beatles and other bands from the British Invasion played a decisive role. But recall that the Beatles decided on that name in imitation of Buddy Holly and the Crickets—a rock ‘n’ roll band formed in Lubbock, Texas in January 1957. So that’s where I’m assigning credit. Buddy Holly launched a trend that lasted roughly a half century, legitimizing collective creativity in a world that usually celebrates individual achievement.

“That’ll Be the Day” was released in May 1957, and became a huge hit during the summer. The sleeve of the album featured the “Chirping Crickets”—and Holly’s name doesn’t even appear, although you can see him in the cover photo. It was the only big hit song of 1957 attributed to a group. But things already started changing in 1958, when the Champs, the Platters, the Coasters, and other bands had songs that climbed the charts.

There was something absurd about the name of Holly’s band—crickets, whether chirping or otherwise, didn’t convey the sense of a bold new movement. Rock ‘n’ Roll deserved something grander, edgier. Yet I note that many radical movements adopt ridiculous names, calling themselves beatniks, hippies, yippies, punks, grungers, or whatever. Even the Internet was originally built on the backs of companies with absurd names—Google, Yahoo, Twitter, etc. We’ve gotten so used to those identities, that the foolishness is forgotten.

That techie lightheartedness is disappearing too, by the way. Google wants to be called Alphabet nowadays. Facebook has adopted the ponderous identity of Meta. The biggest tech IPOs of last year showcased companies with ominous and lugubrious names such as Informatica or Expensify. Yahoos need not apply anymore.

Next week’s quiz: Tech IPO or failed Marvel superhero?

The same taste for absurd names launched the rock rebellion. The Crickets inspired the name Beatles, and soon the strangest animals and objects got turned into revered band identities. Just look at the charts from the following three decades, and scratch your head at the wild zoo on display: Monkees, Byrds, Turtles, Eagles, or just simply the Animals. But, really, anything could provide the name of a huge band, from doors to cars. The only rule was that the name should stop making sense.

Stop making sense.

Stop making sense.

Once again, music fans take all this for granted. But anyone with a larger perspective on the history of music could have figured out the trend wouldn’t last. Since the Renaissance, music has been a star-driven business, focused on individual artists of exceptional talent. The idea that genius would subsume itself in a bizarre collective name is unrealistic. For a time, Brian Wilson was willing to be just a “beach boy” and John Lennon a misspelled beetle. But this wouldn’t last. It couldn’t last.

In fact, the last time the music world embraced collective identities with such vehemence was the medieval era. The surviving musical manuscripts from that period frequently leave out the names of individual contributors. But composers were expected to be anonymous back then—the Church decided which music was preserved, and works were intended for the greater glory of God, not the renown of a single artist.

I tend to view the 50-year period of rock bands as something similar. A kind of spirituality prevailed, even in the thick of the music business. The musicians themselves might be individualists, or even narcissists, but the worldview of rock was about togetherness, sharing, love, peace, and cooperation. I don’t think it’s coincidence that the Beatles, so influential in legitimizing collective bands, kept repeating that same message: come together, all you need is love, we can work it out, with a little help from my friends, etc.

The message couldn’t have been clearer. And when they came to the end, in a song literally called “The End,” they turned it into a moving capstone for their entire legacy:

And in the end,

The love you take,

Is equal to the love you make.

I will sign up for that. It’s as good a mission statement as any I’ve heard.

This was the worldview that somehow blended strong egos into a cooperative ensemble, at least for a decade. And nowadays? It’s not just the band names that have gone missing in action, but the optimistic vibe proclaiming that we can, for all our differences, work it out and come together. That’s no longer the dominant paradigm in our current culture, in case you haven’t noticed.

So I guess I miss the bands—and probably always will—but I miss that attitude of a larger pervasive love even more. If we could regain it, I’m even willing to let musicians call themselves deadmau5 and Juice Wrld or whatever password equivalent they can contrive, with no complaints from me. And if we lose that sense of joining together, even the most audacious individual identities will hardly compensate.

Yes, but . . . don't you think the Crickets were a response to the doo-wop groups, which were all, well, groups? The Orioles (early '50s), the Crows, the Drifters, the Flamingoes (I'll be Home era), the Turbans, the Cadillacs, the Eldorados, the Platters, etc.? Not bands, in that they didn't play instruments, but all collectives. And if you're going to cite Buddy Holly and the Crickets, what about Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys? I get your point, that individuals dominate today, but there are plenty of groups, still, even if they don't dominate the charts.

There was also the Band - perhaps the ultimate example of eschewing individuality for the group collective and ironically, perhaps also the textbook example of how the rise of the individual can tear a group apart.