Special Bonus: A Look at the Expanded 2021 Edition of The Jazz Standards

Here are two songs from my new guide to the 267 essential jazz compositions

A few days ago, the revised and expanded edition of my book The Jazz Standards was published by Oxford University Press. I’ve never had more fun writing a book than in creating this guide to the jazz repertoire—which covers 267 essential songs. These were songs that I first learned in my earliest days as a jazz musician, and they’ve remained familiar friends over the decades.

The first edition of The Jazz Standards, published in 2011, earned praise from Sonny Rollins, Dave Brubeck, Lee Konitz, and other jazz luminaries—a tough audience to please, because they know these songs intimately. I must have done something right to get their approval. But the full range of the response to The Jazz Standards went far beyond my expectations. In fact, more readers contacted me in response to this book than about anything I’ve ever published.

These were more than fan letters, but smart responses from readers who also felt a deep affinity for the jazz repertoire, and had things to tell me. Many shared new information on the jazz songs I’d written about in the book, some of them providing details never previously published. I started taking notes of all the new stuff I wish I had included in the book. Meanwhile my own further research gave me additional insights into these old jazz songs. I gradually realized that a revised edition was warranted—a move that would also give me a chance to include additional songs.

Oxford University Press gave me the green light to pursue this updated and expanded edition, much to my delight. We decided to pursue it in tandem with the new third edition of The History of Jazz, which was published in March. I suggested that we release these two updated books as companion volumes, which the new cover designs (below) convey.

As a special feature for subscribers to The Honest Broker, I’m sharing below entries on two songs from the book.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, arts, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Moose the Mooche

Composed by Charlie Parker

What does it take to get your name attached to a jazz standard? Emry Byrd, a shoeshine stand operator on LA’s Central Avenue known to friends and clients as “Moose the Mooche,” was a polio victim who could only move around on crutches or in a wheelchair. But Charlie Parker didn’t name a song after him out of pity or compassion; rather, it was a relationship of dependency. Byrd sold drugs out of his stand, and was Parker’s heroin supplier during the musician’s early days in Southern California.

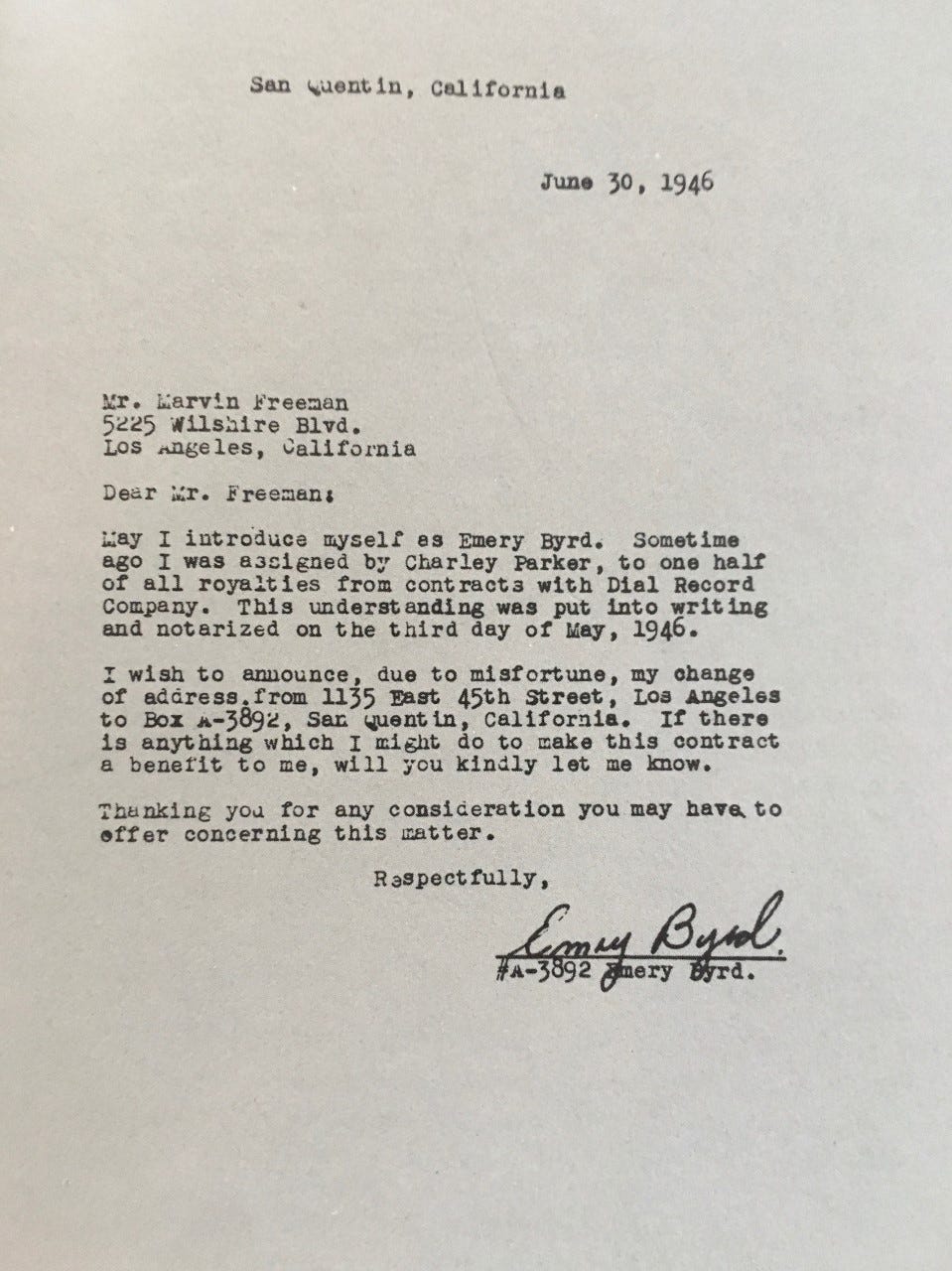

But the story of Bird and Byrd gets more interesting. In an unprecedented move, Moose the Mooche not only got a song named in his honor but somehow managed to secure rights to half of the royalties to Charlie Parker’s recordings for the Dial label. Only a few weeks elapsed between Parker signing a deal with Dial (on April 3, 1946) and his subsequent assignment of rights to Byrd in a notarized document (dated May 3, 1946)—no doubt in exchange for services rendered. Byrd’s next appearance in Parker’s biography comes in the form of a letter the drug dealer sent to Dial Records (dated June 30, 1946), requesting that all future payments be sent to his new address at San Quentin penitentiary.

You can accuse Parker of short-term thinking, but that’s also how this song was composed. Roy Porter, the drummer on the date who drove Bird to the session, later claimed that “Moose the Mooche” was written during the short trip to the recording studio—with the first notes sketched in the vicinity of 35th and Maple Street in Los Angeles, and the chart finished before they drove up in front of Radio Recorders, located at 7000 Santa Monica Boulevard. I accept the possibility of this, given the 10 mile distance involved, but Parker must have already had most of this melody in his head before putting it down on paper.

It’s certainly one of his finest efforts. Most bebop charts are filled with long, complex phrases—and Parker himself wrote many of that sort. But “Moose the Mooche” is constructed out of short, choppy jabs. Much of its power derives from declamatory three-note phrases in the higher register, alternating with more chromatic asides in the lower register. Even when played by a single horn, it almost sounds like a conversation between two lovers, but more passionate than tender.

The chords are just the familiar “I Got Rhythm” changes so popular with jazz musicians. Bands usually play ‘rhythm changes’ fast, and Parker recorded the song at around 200 beats per minute, and most of the later recordings of the song are even faster. In his live recordings, Parker typically played it at more than 250 bpm. Check out, for example, his 1953 sprint through “Moose the Mooche” at Birdland alongside pianist Bud Powell.

Lately I’ve noted a growing reluctance among rising jazz stars to play bebop songs at the blistering tempos of yesteryear. That’s a shame, because there are few things more exhilarating than hearing a top tier band off to the races on rhythm changes. “Moose the Mooche” can adapt to different approaches, for example the shifting metrics of Aaron Goldberg’s rendition, or Joe Lovano’s slow stroll through the chart. But this is still one of the best songs for occasions when restraint is thrown aside and jazz high-jinks are in order.

RECOMMENDED VERSIONS

Charlie Parker (with Miles Davis), Hollywood, March 28, 1946

Bud Powell (with Charlie Parker), live at Birdland, May 29, 1953

Shelly Manne (with Charles Mariano), from More Swinging Sounds, Los Angeles, August 15-16, 1956

Art Blakey (with Philly Joe Jones and Roy Haynes), from Drums Around the Corner, New York, November 2, 1958

Barry Harris, from Barry Harris at the Jazz Workshop, recorded live at the Jazz Workshop, San Francisco, May 15-16, 1960

Hank Jones (with Ron Carter and Tony Williams), from The Great Jazz Trio at the Village Vanguard, recorded live at the Village Vanguard, New York, February 19-20, 1977

Warne Marsh, from Star Highs, Monster, Holland, August 14, 1982

Joshua Redman, from Wish, New York, 1993

Roy Haynes (with Kenny Garrett and Roy Hargrove), from Birds of a Feather, New York, March 26-27, 2001

Joe Lovano (with Esperanza Spalding), from Bird Songs, New York, September 7-8, 2010

Aaron Goldberg with Miguel Zenón, from Bienestan, Brooklyn, New York, May 13-14, 2011

Don’t Get Around Much Anymore

Composed by Duke Ellington, with lyrics by Bob Russell

Many listeners over the years have assumed this song was called “Mister Saturday Dance” based on a common mishearing of the opening lyrics (“Missed the Saturday dance . . .”). But my favorite garbling of the title came from an inebriated regular at a bar where I once played the piano. He stumbled up to the keyboard late one night, after another evening striking out with the ladies, and asked me if I knew how to play “Don’t Get Much Around Here Anymore.”

The song originated as a counter-melody composed for “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart” that got recycled into “Never No Lament,” which Ellington recorded with one of his finest bands in 1940. This peculiar version leaves out the B theme and final A theme recapitulation in the opening statement. Ellington frequently broke the rules of song form during this period, but this particular “innovation” will sound quite odd to anyone familiar with how this song is typically played nowadays. There are compensating factors, however: the melody serves as an ideal vehicle for alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges—who, according to Rex Stewart, may have provided the riff that originally inspired the song—while Cootie Williams also contributes an outstanding solo.

By 1942, lyrics by Bob Russell were added, and the song had been rechristened as “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore.” Yet the world-weary words seem at odds with the merry-making music. When Ellington presented the composition at Carnegie Hall, as part of the famous concert that also saw the debut of his magnum opus Black, Brown and Beige, he announced it under the new name but retained the anomalous opening half-chorus from the studio recording. The lyrics were not featured, and the melody was still assigned to Hodges, who played it with, if anything, even more passion than on the 1940 recording.

In March of that same year, an understated cover version by the Ink Spots, brandishing their sweet barbershop harmonies, reached the top of the R&B chart. This success gave Ellington a stunning, if pleasant, surprise soon afterward, when he strolled into the William Morris Agency office, hoping to borrow a few hundred dollars. While he was waiting, an office boy gave him a letter that had been sitting around for him. Duke opened it to find a check for $22,500—all due to “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore” and fueled by the Ink Spots’ big hit.

The ASCAP strike prevented Ellington from seizing the opportunity with a vocal version of his own; he wouldn’t release one until 1947. But his label reissued his 1940 recording under the new name, and it also reached the top of the R&B chart in late May. The song never left his repertoire in later years. Given its popularity, “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore” was demanded by audiences wherever Duke performed, but he often slipped it into the dreaded (at least by many Ellington devotees) “medley” that he frequently used to get such requests out of the way.

If any vocalist owned this song, it was Al Hibbler, who joined Ellington’s band in 1943 and stayed on for eight years. He recorded “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore” on many occasions, but my favorite, hands down, is the version he made with Rahsaan Roland Kirk in 1972. For this project, Hibbler engages in his trademark hemming and hawing, which makes it sound as if he is making up the lyrics as he goes along. Kirk, for his part, acts as if he is auditioning for some demonic rhythm-and-blues band. Even Duke, a connoisseur of unconventional sounds, must have been envious.

Like many Ellington hits, this one shows up in surprising places. Paul McCartney performed an old time rock-and-roll arrangement of the song on his 1987 “Soviet” album CHoBa B CCCP, and his version is quite endearing. After hearing this track, one might almost think that Little Richard or Chuck Berry had written the tune. Other unexpected covers of this song include a rendition by Harry Connick Jr. for the soundtrack for When Harry Met Sally and Willie Nelson’s heartfelt performance on his platinum Stardust release from 1978.

Yet for all its popularity—and it does get around much, the title notwithstanding—this song is devilishly hard to update into a modern jazz version. The melody almost demands a conventional swing rhythm and the harmonic sequence does not rank among Ellington’s most inspired. For that reason, this standard is rarely performed by the younger generation of progressive players who probably find it easier to relate to Duke’s ballads than to a dance-oriented number of this sort.

RECOMMENDED VERSIONS

Duke Ellington (recorded as “Never No Lament”), Los Angeles, May 4, 1940

The Ink Spots, New York, July 28, 1942

Duke Ellington, live at Carnegie Hall, New York, January 23, 1943

Duke Ellington (with Al Hibbler), New York, December 20, 1947

Ella Fitzgerald, from The Duke Ellington Songbook, Los Angeles, September 4, 1956

Mose Allison, from Young Man Mose, New York, January 24, 1958

Johnny Hodges (with Billy Strayhorn), from Soloist, New York, December 11, 1961

Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Al Hibbler, from A Meeting of the Times, New York, March 30, 1972

McCoy Tyner, from Solar, live at Sweet Basil, New York, June 14, 1991

Dr. John (with Ronnie Cuber), from Duke Elegant, New York, 2000

Thank you for pointing me to the Kirk vs Hibbler track. Rashaan is one of my most beloved musicians. To me he was a man who could 'by mere playing go to heaven.' I often think about the time I saw him in a small club in Boston in '71 or '72. He was honest, and open with the audience, glad to reply to comments, even if they were scary. One of the audience had a big meat cleaver and said something like 'bring the revolution' to Rashaan. Of course he was blind to the cleaver, but still calmly talked the fellow down. Kirk fully utilized the power of music to excite, surprise, elevate, communicate bare painful truth.

Interesting background on "Don't Get Around Much Anymore". The title has a timely meaning for many people nowadays. I lost my sense of smell and taste in December 2019 which means that I haven't been to a restaurant since then. I would have to go with the Johnny Hodges Billy Strayhorn version as my favorite.