Six Remarkable Facts About Nobel Laureate Czesław Miłosz

A new book on the famous writer's exile in Berkeley is filled with surprises

As a longtime resident of the Bay Area, I was charmed when I first learned that the greatest Polish poet of the late 20th century lived in Berkeley. But the reasons so many immigrant artists end up in California are usually more tragic than uplifting—although it’s sometimes hard not to look with amusement at the bizarre juxtapositions they create.

Consider this reminder, from Google maps, that Austrian avant-garde composer Arnold Schoenberg’s home in Los Angeles is a short walk away from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air house.

What’s even odder is that both homes served as shelters for exiles. Even the Fresh Prince moved to SoCal because his life got “twisted upside down” in his native West Philadelphia. That’s a sad story (reenacted at the start of each episode), but hardly as unsettling as Schoenberg fleeing the Nazis who condemned him as a composer of degenerate music, banned the publication of his works, and no doubt would have killed him if he had remained at his teaching post in Berlin.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Similar stories can be told of Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht hanging out in Santa Monica and its environs, where their neighbors included Alma Mahler-Werfel, the widow of Gustav Mahler, and philosopher Theodor Adorno. Igor Stravinsky, in contrast, was living on North Wetherly Drive in West Hollywood, not far away from Whisky a Go Go—he could have strolled down there to watch Alice Cooper record a live album at the club in 1969.

I was a young boy in Los Angeles back then, and my notion of these neighborhoods was so different from my later impressions of Mann, Schoenberg, Brecht, Stravinsky, and others. How could they possibly reside in such settings? Could Mann really write Doctor Faustus a few minutes away from Muscle Beach? Did Schoenberg actually take a break from his austere composing to play tennis with George Gershwin in Hollywood? It’s all true. But they didn’t make these unexpected moves to amuse us. Necessity and banishment created these unusual connections.

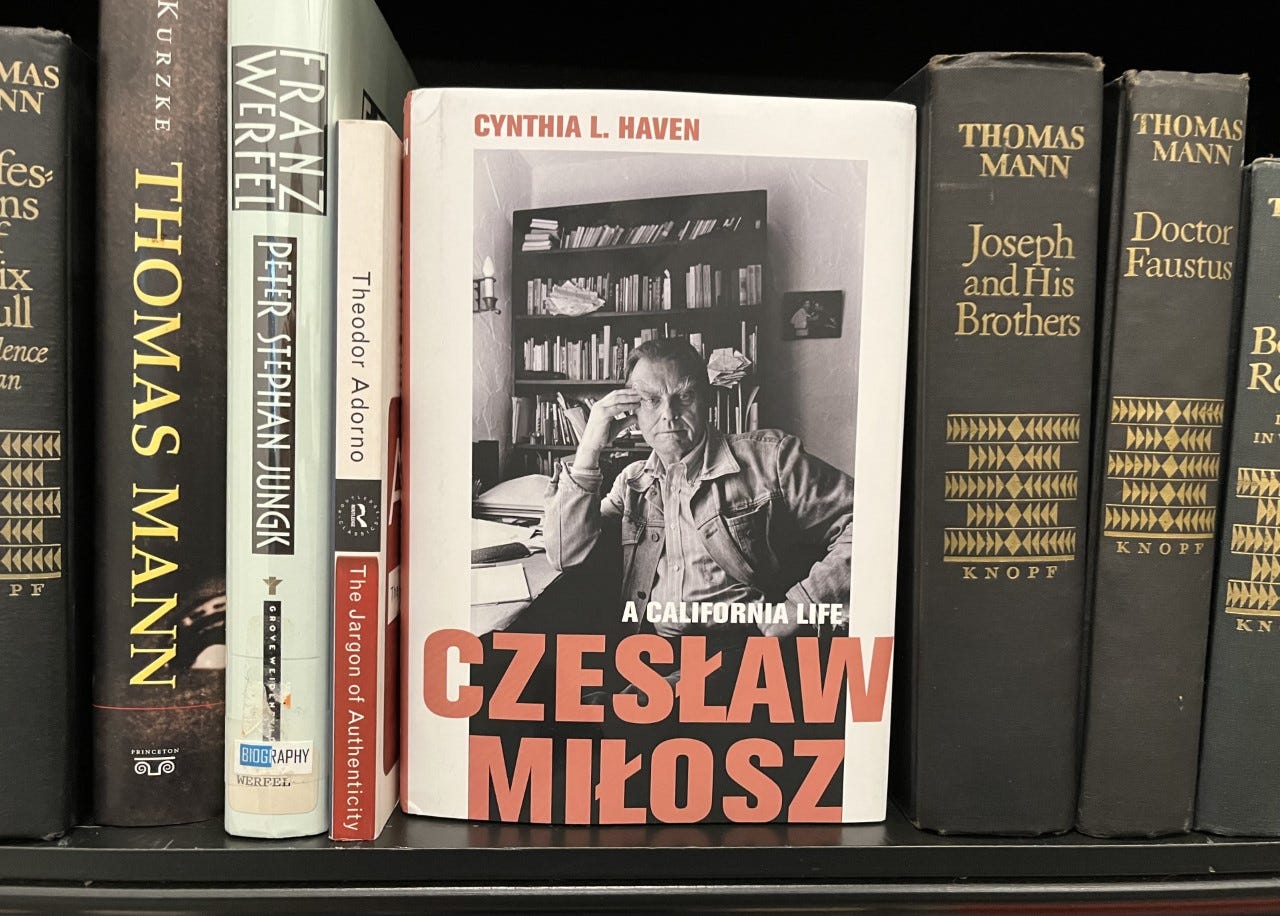

Until recently, I knew less about the exile of Nobel Prize laureate Czesław Miłosz at Berkeley. But the publication of Cynthia Haven’s outstanding new book Czesław Miłosz: A California Life has cut through the enigma of how one of the defining figures in European poetry survived—and perhaps even thrived—amidst the most rebellious and uninhibited center of youth culture in the United States.

Haven understands that this dramatic setting isn’t just a minor part of Miłosz’s story, but encapsulates so many of the powerful themes defining this poet’s life and work. And through Miłosz we can comprehend more fully these other seminal figures of exile in modern culture. Perhaps artists are always strangers in a strange land, but in the course of modern times, they often became literal nomads and outcasts, bringing their intangible gifts to unfamiliar, even hostile terrains. Haven’s probing and sensitive book goes a long way toward solving the mystery of how personal dislocation can spur creative expansion.

Miłosz arrived on the Berkeley campus in the early 1960s and even a native Californian would have found that setting full of surprises over the next few years. How could the profound eminence who wrote The Captive Mind, one of the most darkly skeptical and still-all-too-relevant memoirs of the Cold War, even coexist for a semester with the happenings on Telegraph Avenue and in People’s Park? Yet Miłosz lived in Berkeley for almost half of his long life, not only navigating through these turbulent settings, but in some ways discovering his own inner resources and capacities along the way—so much so that he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1980. Miłosz is still the only UC Berkeley faculty member to gain that particular honor. All the other Berkeley Nobel honorees have been economists or scientists.

Below are the six most inspiring things I’ve learned about Miłosz, most of them thanks to Haven’s book.

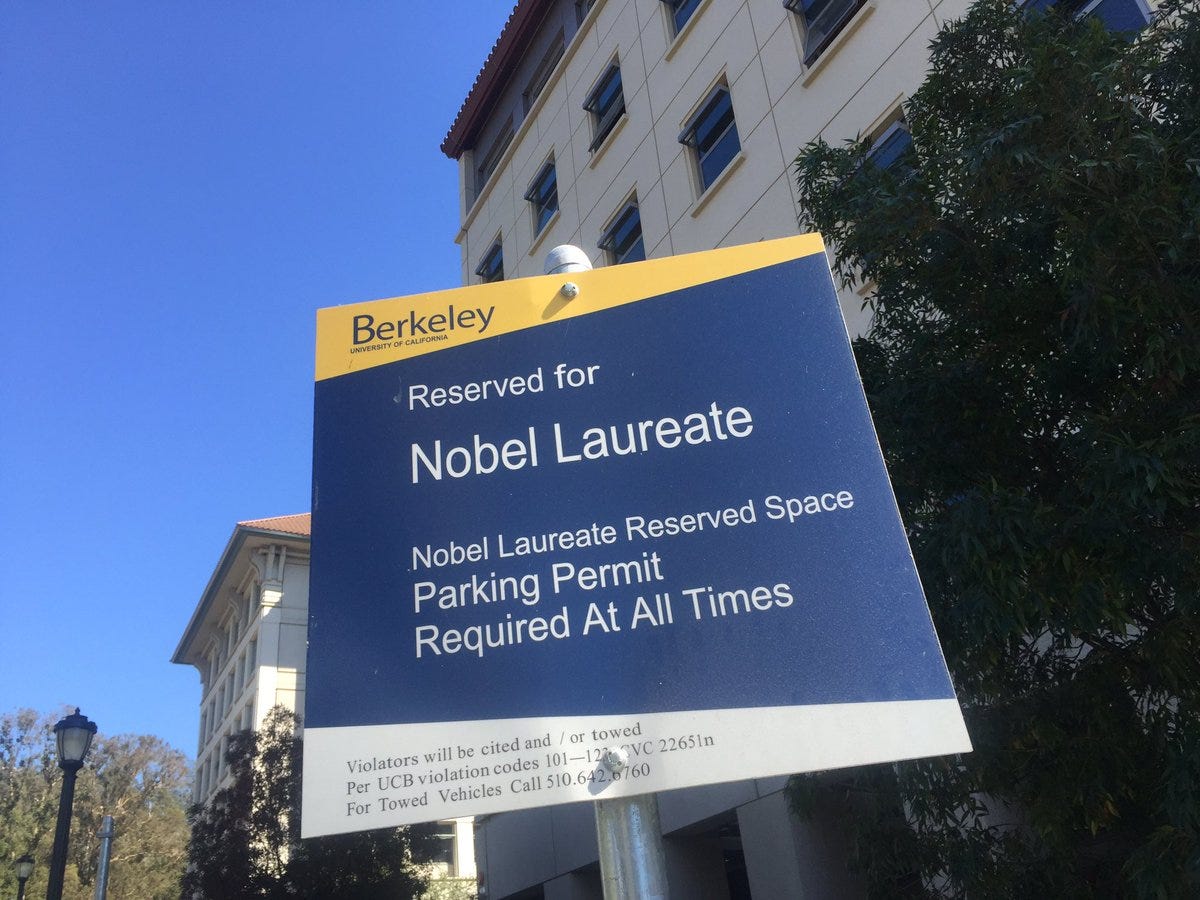

(1) Let’s start with the famous parking spots at Berkeley, which you can only use if you win a Nobel Prize. I probably find this all the more striking due to the countless times I’ve circled block after block near the UC campus trying to find a parking place. For a period of several years, I visited Berkeley two of three times every month—to see friends, go to concerts, visit bookstores and record stores, etc.—and the parking problem was (in the words of my computer science professor) a non-trivial task. I certainly took the poet’s profession more seriously after I learned that success in that field could result in such extraordinary rewards.

By the way, I once got into a physical altercation with a Nobel laureate (well, he caused it, to be honest). But that’s too long of a story to include here. I raise the matter simply because I sometimes like to imagine two Berkeley Nobel Prize winners arriving simultaneously in their expensive cars at this parking spot, ready to battle over a tiny but coveted parcel of California real estate—perhaps even stepping out of their vehicles to prove whose laureate’s laurels are the longest.

(2) On a more mystical note: I was moved by the miraculous way Miłosz escaped from a German prison camp in 1944. Haven provides these details:

“He got out of Poland by a miracle—except in a city that had only 6 percent of its population left, each survivor is a miracle. . . . In 1944 Miłosz was caught by the Germans and put in a makeshift camp. A majestic nun appeared that evening, insisting he was her nephew. For an hour, she spoke fluent German with his captors, and then led him away through the main gates. He had never seen her before, and he never saw her after that day. He never knew her name.”

That’s an extraordinary story. If you put it in a movie, audiences wouldn’t believe it for a moment. Only heroes rescue people from such dangers, not total strangers dressed in a convent habit. Yet it not only happened, but made everything else in the Miłosz story possible.

(3) The FBI agent who was assigned to spy on the Miłosz family, fell in love with the poet’s wife, and tried to steal her away. Now this is truly a subject fit for a film or TV series. Haven writes:

“One of the FBI agents assigned to her case fell in love with her and begged her to marry him, promising to be a father to her sons. Janka had spent years longing for quiet and security, and now this man was offering it, and she would finally be able to settle down and live as a family in a modern American home in the burgeoning postwar suburbs. He told her there was no future with Miłosz. . . .”

That’s a powerful rival—one who not only can predict, but perhaps even cause, your failure and destruction. And it must have been an attractive proposal. But she turned it down.

(4) Janka Miłosz plays a starring role in this next incident too. After her husband went to Paris, he was repeatedly denied permission to return to the United States. His wife worked tirelessly to get him a visa and reunite the family, even lobbying those at the highest levels of the government, including Secretary of State Dean Acheson.

But her finest moment came when she angrily confronted a bureaucrat at the State Department, shouting in his face: “You’ll regret it, because he is going to win the Nobel Prize.” Haven adds: “Back then, it must have seemed an impossible bluff, a wild shot fired in the darkness.” But decades later, Miłosz actually did win that predicted Nobel Prize.

(5) Here’s an insight into the more poetic side of Miłosz. What do you think he considered the most impressive and surprising aspect of California? Maybe Hollywood or Silicon Valley or the surfers on the beach?

No, none of those.

In a key passage, the exiled poet once described, with rare enthusiasm, his rapt admiration for a different aspect of Western living. Back in Europe, he had only known about one kind of pine tree. “A pine tree is a pine tree,” Miłosz explained. But not in California:

“Here suddenly there was the sugar pine, the ponderosa pine, the Monterey pine, and so on—seventeen species all told. Five species of spruce, six of fir. . . . Several species each of cedar, larch, juniper. The oak, which I had believed to be simply an oak, always and everywhere eternal and indivisible in its oakness, had in America multiplied into something like sixteen species, ranging from those whose oakness was beyond question to others where it was so hazy it was hard to tell right off whether they were laurels or oaks.”

Consider giving a gift subscription to The Honest Broker this holiday season.

I find this passage extraordinary, and a reminder of how different poets are from the rest of us. How many native Californians know that seventeen different species of pine appear on the American landscape? Most of us are too busy trying to find a parking spot.

(6) My final observation on Miłosz is a more melancholy one. But perhaps this is fitting for a figure who came of age in such a dangerous time and place. (Poland, as Haven reminds us, possesses “the distinction of having lost World War II twice”—conquered first by the Nazis, and later by the Soviet Union.)

Miłosz often complained that his students—and perhaps most Americans—lacked a “historical consciousness.” Yet when asked to explain what this grasp of history involved, he responded in a way that shocked me: “This awareness was half a knowledge of history and half a knowledge of evil.”

What a disturbing way of considering the study of history! Yet, upon closer consideration, I’m forced to agree with Miłosz’s gloomy assessment. So many of the mistakes made by powerful institutions and figures in our own time seem to arise from pure ignorance of the evils that human beings—often with the highest intentions—are able to inflict on one another. A close student of history soons learns the absurdity of this unwarranted optimism, so endemic to our technocratic times.

Miłosz felt that he had an advantage in grasping this profound connection between history and evil. He once remarked:

“I feel that the greatest asset that my part of Europe received in the history of the twentieth century, the privilege of our being the avant-garde of inhumanity, is that the question of true and false, good and evil, became operative again. Namely, good and evil, true and false have not been discovered through philosophical discourse, but empirically like the taste of bread.”

That’s not a kind of consciousness you expect to come out of life in sunny California. But maybe it’s precisely the type of learning we need to counter all those other things emanating from the Western shores, whether from Silicon Valley boardrooms or reality TV shows or elsewhere. Czesław Miłosz was far more real than the realest housewives of any of those benighted series. It’s a painful dose of reality he was given, but we do well to let him pass it on to us.

Thank you for being one of the last literate writers left in the US.

Reads like a detective story!