Six Recent Studies Show an Unexpected Increase in Classical Music Listening

Something has changed in the last 12-18 months, especially among younger listeners—but why?

Last year, I went viral with an article about the rising popularity of old music. But I focused on old rock songs. Many of these songs are 40 or 50 years old. And in the world of pop culture, that’s like ancient history.

But if you really want old music, you can dig back 200 or 300 years—or even more, if you want. But does anybody really do that?

Conventional wisdom tells us that only around 1% of the public cares about classical music. And it doesn’t change much from year to year.

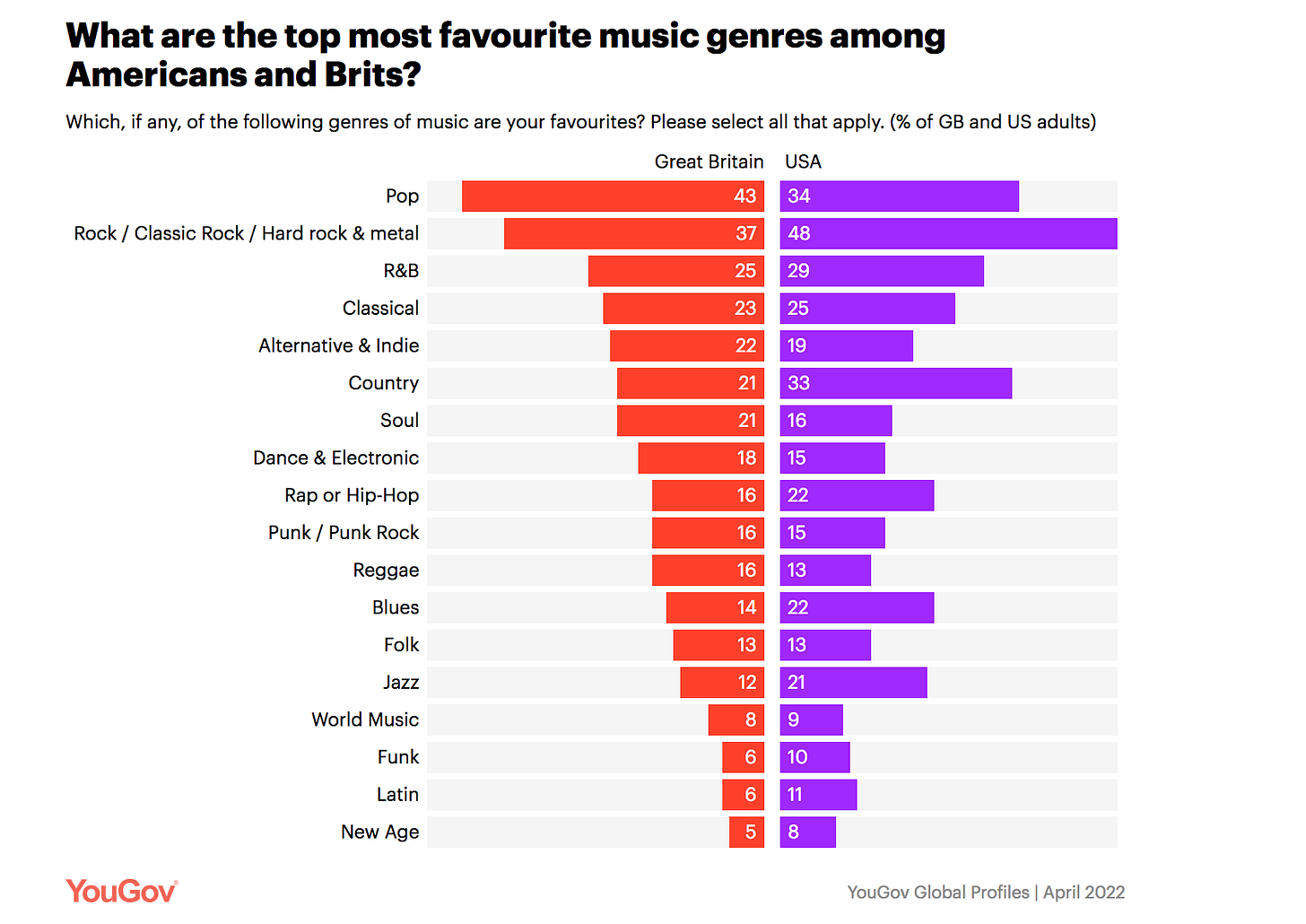

For proof, just take a look at this chart:

If you love concerts at the philharmonic, you read these figures with much weeping and gnashing of teeth. If classical music were any smaller, it would be a rounding error. Or—even sadder—it would be like jazz.

But that data only covers the period up to 2021. And 2022 was different.

In fact, it was remarkably different.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture.

Both free and paid subscriptions are available.

If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Over the last 12 months, I’ve started to see surprising signs of a larger audience turning to classical music. Last year, I wrote about the amazing saga of WDAV, the first classical music radio station in US history to take the top spot in its city.

I analyzed the numbers, and tried to get to the bottom of this unexpected success story. At the time, I wrote:

Women are the key drivers here. The station boasts a double-digit share in the female 35-44 category. But this probably is tilted heavily toward mothers, at least if we factor in the next bit of evidence—which reveals that WDAV has a mind-boggling 38% share among young children.

But then a few weeks later, this research report was issued:

I need to point out that respondents were allowed to mention multiple genres—but even given that loophole, who would expect classical music to rank ahead of country music, hip-hop, or folk?

This can’t be true. The numbers must be wrong. Or, maybe, people are lying to pollsters.

But then a survey of holiday listening trends in the UK revealed the unprecedented popularity of orchestral music—especially among younger listeners.

According to the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra:

The national poll of 2,000 adults turned on its head the long-held assumption that orchestral music is a music genre for older people. Instead, the RPO study revealed that 74% of people aged under 25 will engage with orchestral music this Christmas, compared to just 46% of people aged 55 or over.

The RPO shared more demographic data in its annual report, published a few days ago—including the fact that “more people are listening to orchestral music today as part of their daily lives than was the case before the pandemic (59% up from 55% pre-pandemic)” and the trend is “strongest among younger people.” A previous post-pandemic research project by the same organization indicated that “78% of under 25s were interested in experiencing an orchestral concert this year.”

And according to the BBC, still another survey reveals that “under 35-year-olds are more likely to listen to orchestral music than their parents.” The article also notes that the hashtag #classictok on TikTok has generated 53.8 million views.

“Whatever the reasons, the impact is clear. Starting about 12-18 months ago, something shifted in music consumption patterns.”

Could something similar happen in opera?

Maybe it’s already starting. The Met has more than its share of problems, but paid ticket sales are up and the audience is surprisingly young. “Single ticket buyers represent 75% of our sales and the average age of a single ticket buyer is now 45 years old, which is remarkably younger than it was,” Peter Gelb remarked a few days ago.

And, in the strangest twist of all, the Met is having great success with brand new operas by living composers. Both Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones and Kevin Puts’s The Hours have attracted sellout crowds.

Blanchard seems to be morphing into an opera composer in this new stage of a variegated career. But he isn’t the only jazz musician to make that leap. One of Wayne Shorter’s final projects was the opera Iphigenia, created in collaboration with Esperanza Spalding. Here, too, performances were sold out.

What’s going on here?

Maybe that old orchestral and operatic music now sounds fresh to ears raised on electronic sounds. Maybe the dominance of four-chord compositions has created a hunger for four-movement compositions. Maybe young people view getting dressed up for a night at the opera hall as a kind of cosplay event. Or maybe the pandemic had some impact on music consumption.

And it’s true, the pandemic did cause a major increase in the purchase of musical instruments. People got serious about music—so much so that they wanted to play it themselves. Perhaps it changed listening habits too.

But whatever the reasons, the impact is clear. Starting about 12-18 months ago, something shifted in music consumption patterns.

Not long ago, I would have shaken my head in disbelief at this report. But given all the converging survey data shared above, I can only conclude that the culture is shifting in some meaningful way.

Given these findings, the success of classical musicians on social media should come as no surprise. With just a quick search, I found many young classical musicians with 100,000 or more followers on Instagram.

Consider the case of French violinist Esther Abrami—who boasts 275,000 YouTube subscribers, 255,000 Instagram followers, and 380,000 fans on TikTok. Her video performance of Libertango has gotten more than one million views. Okay, maybe that won’t put Taylor Swift out of business, but it proves that Astor Piazzolla’s music can speak to a mass audience.

Not all of this music fits into traditional notions of classical decorum. Piazzolla only operates on the fringes of the concert hall repertoire. But other examples of crossover classical on social media are even more non-traditional. For example, Nigerian American opera singer Babatunde Akinboboye mixes up Rossini with Kendrick Lamar—and calls his concoction hip-hopera. But he can also sing The Barber of Seville without any postmodernist tricks, and deliver the goods.

I’ll let others critique these mash-ups. For my part, I’ve never been obsessed with scrupulous historical authenticity. I’m happy to see Shostakovich’s chamber music promoted as “heavy metal on strings”—I think that’s an apt description. (If you doubt it, listen to the same work performed on electric guitars.) These reframings of old sounds attract tens of thousands of new listeners, and I have a hunch that Shostakovich himself would have been pleased.

Any vibrant genre should have many different entry points—and that’s always been the case. I loved the Flash Gordon theme song when I was a child, and only later learned it was composed by Liszt. And, over the course of decades, millions of American couch potatoes binging on TV learned about Rossini through The Lone Ranger.

If you fear that this populist connection harms the dignity of the operatic repertoire, you don’t really know the history of the idiom. Rossini was providing populist entertainment long before he got turned into a purveyor of highbrow culture for elites.

But there are other ways of bringing classical music to new listeners. Harriet Stubbs, for example, has explored a different approach, playing 20-minute concerts at her London flat, and opening the windows so passers-by can hear. It seems like a tiny gesture, but she may have reached a half million pedestrians by giving 250 of these concerts.

“People who thought they didn't care for classical music came back every day because of the power of that music," she later reported. And that’s the key point. How people start the relationship with classical music is less important than where they take it.

By all indications, they are now taking it further than anybody anticipated. And by my measure, this culture shift is still in the early stages.

I’ll make one last point—and it very much needs to be made. There’s heavy irony in the fact that major institutions (such as the BBC) are sharply cutting back their support of classical music right now.

Just last week 462 composers and musicians signed a petition protesting the BBC’s massive cuts to classical music. (The BBC responded with a bland form letter marked by errors.)

This is actually the moment when the BBC and others should be doing the opposite. They should go with the momentum, not fight against it.

Of course, that implies a reversal of everything we thought we knew about the genre. In the past, elitist institutions gave classical music support because the grassroots audience was so small. Now the resurgence is happening on the ground level, and the petrified institutions that dominate our culture aren’t even paying attention.

I could lament this gap between perception and reality. But instead I prefer to celebrate it. What’s happening among the audience is what really counts. That’s always been true and always will be true. If powerful decision-makers at the BBC and elsewhere don’t recognize this, that’s their loss.

This shift started with little or no support from the top. And it may even become more vibrant if out-of-touch mangers and administrators aren’t involved. They can be heavy-handed when they barge into a music scene, or haven’t you noticed? We invite their participation—but, honestly, we will almost certainly have more fun without it.

How many kids like me in the 1950’s and 1960’s were introduced to classical music via Looney Tunes?

One side comment. When one gets into the 6th and 7th decade of life-the desire to hear certain popular AM/FM radio songs for the umpteenth time loses its attraction.

This makes a ton of sense. Most of the teenagers I've worked with have, at some point, shared similar frustrations about detesting the older generations' beliefs that they are more superficial, less-intelligent, and less capable than their elders. Combine this with a drive towards drifting back towards the real world (total time spent on the internet is trending downward with time, not upward anymore), and this may be part of a counter-cultural response towards rejecting where we've been over the past decade or so and where we're going. If this is true, I'm very much along for the ride!