My Warning About AI Music from 1988

Did I get it wrong or right? You tell me.

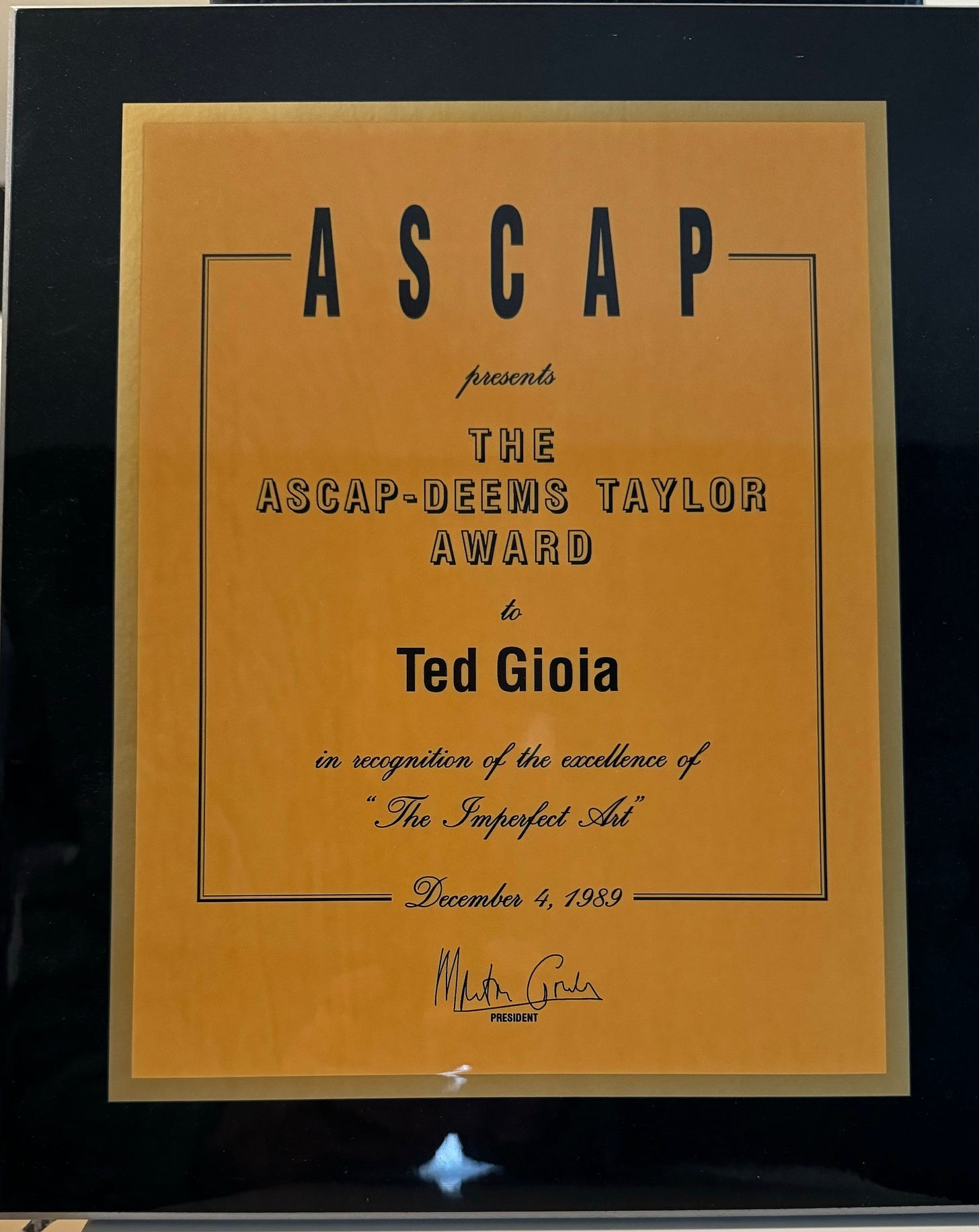

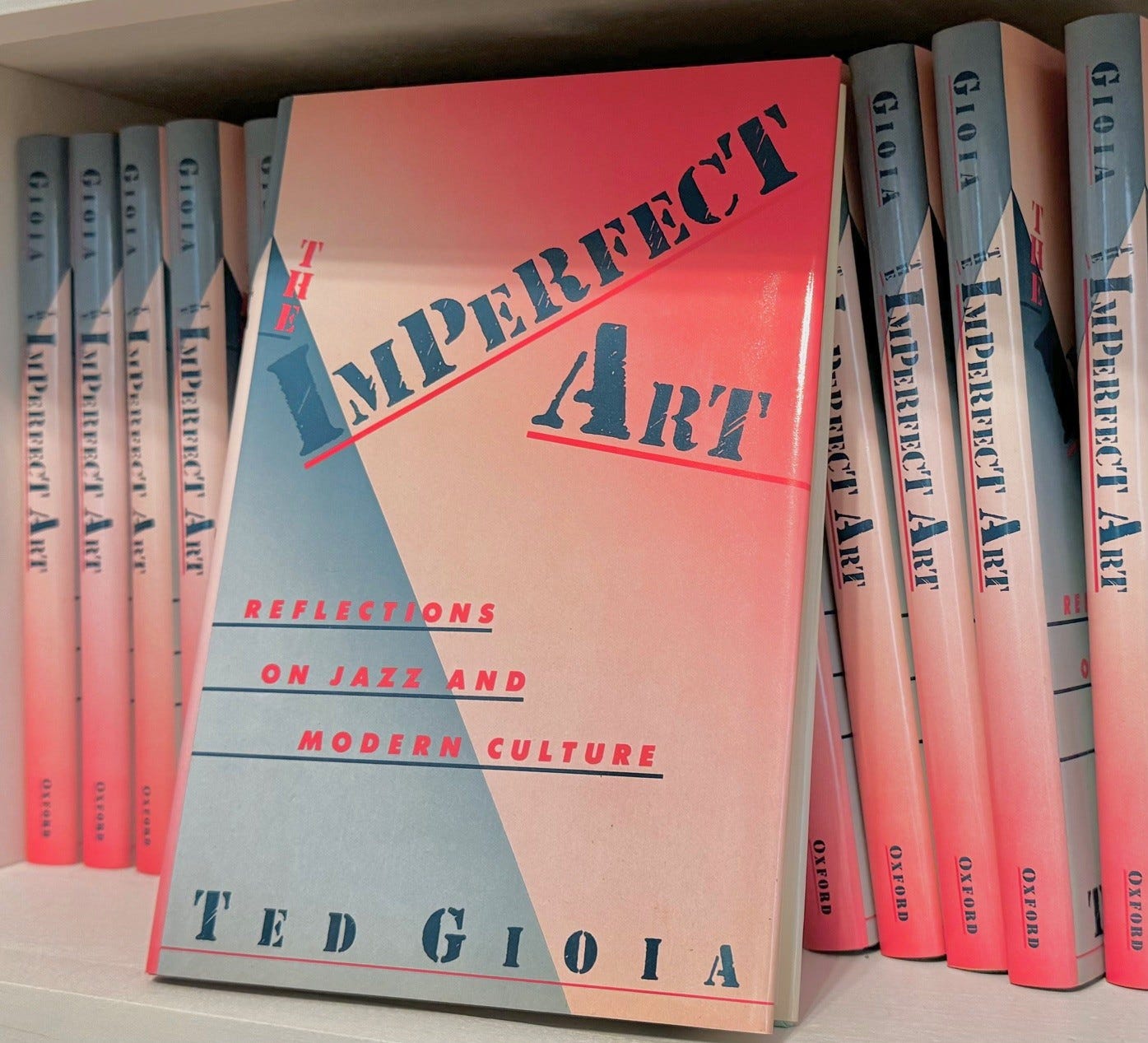

At the very start of my career, I wrote a book called The Imperfect Art—and it’s still finding new readers today. Just last week I learned that a Chinese translation is underway. A Spanish translation will also soon get published.

I started writing this book when I was still a student—more than forty years ago. So it’s ongoing popularity is very pleasing to me. I always try to write works that readers will still value in the future. But it’s rare that you live long enough and see this actually happen.

But in my case, I wrote a book that might be even more relevant today than when it was first published—as you will see below.

In The Imperfect Art, I celebrated the human element in jazz. Even flaws and blemishes are part of its beauty, I claimed.

If you’re a jazz soloist, your goal isn’t perfection. That’s for machines. Art is expressive of the human condition—and that’s always a messier affair. Miles Davis taught me that even mistakes can make a solo better, not worse.

The late Jim McNeely, a fantastic jazz composer, said something similar in a discussion of recordings by Miles’s longtime collaborator Gil Evans.

Some of Gil’s writing was so rhythmically tricky to play that the recordings that Gil did are full of these little mistakes that the players make, and when you hear it recorded later by other ensembles, where they’re nailing it, it sounds weird….

On Gil’s own recordings, the word I keep thinking of is there’s a charm about those, because they weren’t played perfectly….

There’s this humanness of the rough edges on Gil’s original records that to me are just beautiful.

That was part of what I was trying to convey as young music critic in my defense of the human element in creative works. To many people, this seems paradoxical. How can errors make art better? But once you’ve encountered it again and again, you realize that expressive creativity isn’t like a math problem—it’s more a matter of heart and soul.

Some day I will write an article about my favorite mistakes in music. There are plenty to choose from.

By the way, sports are no different. If NBA players were perfect, and never missed a shot, fans would quickly lose interest.

Please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

This extract from my first book has been widely quoted over the years. And it helped launch a new approach to art—known today as imperfectionist aesthetics.

Imagine T.S. Eliot giving nightly poetry readings at which, rather than reciting set pieces, he was expected to create impromptu poems—different ones each night, sometimes recited at a fast clip; imagine giving Hitchcock or Fellini a handheld camera and asking them to film something—anything—at that very moment, without the benefits of script, crew, editing, or scoring; imagine Matisse or Dali giving nightly exhibitions of their skills—exhibitions at which paying audiences would watch them fill up canvas after canvas with paint, often with only two or three minutes devoted to each ‘masterpiece.’

These examples strike us as odd, perhaps even ridiculous, yet conditions such as these are precisely those under which the jazz musician operates night after night, years after year.

I published this at the end of the 1980s—a long, long time ago. But even back then I mentioned the possibility that machines might some day make music that was technically perfect.

The idea didn’t appeal to me back then. And it still doesn’t today. But here’s what I wrote in 1988.

Imagine a computer that has been programmed to compose musical works in any style. Even if the computer produced works stylistically and qualitatively indistinguishable from Mozart’s, we would still be unwilling to consider them as comparable to the Austrian composer’s pieces. The two are incommensurable. Mozart’s works are artistic masterpieces, and the computer’s output, however admirable, is something else entirely. The latter’s perfection no more reflects on the composer’s art than the existence of motor boats affects our judgment of how difficult it is to swim across the English Channel.

Thus, not only is our interest in the human element in art a justifiable concern, it is in fact a necessary concern….Art, in the words of the great modern aesthetician Benedetto Croce, is “expressive activity,” and lives and dies by the success of that expression.

I wouldn’t change a word of that today. In fact, this is more urgent to understand now than it was back then.

Art is a human expression. That’s why we don’t consider a sunset or rainbow as works of art—no matter how beautiful they are. The essence isn’t the beauty, it’s that persnickety human ingredient.

Without it, you don’t have art. That’s true no matter what an AI song sounds like. Or how much money it makes.

You don’t need to be a critic or philosopher to figure this out. People call this stuff slop because they know instinctively how different it is from human creative work. They feel repulsion when confronted by it.

It’s like visiting a wax museum. The attempt by the inhuman to imitate the human is always creepy.

And the more closely the machine replicates a human, the creepier it gets.

This is a categorical divide that can’t be fixed with more AI training and software upgrades. Art is part of human culture, not machine learning—and the gap will never be bridged.

That’s what I said when I was in my twenties, and I put it in my book.

Did I get it right or wrong? What do you think?

I heard that Persian rugs makers woukd always tie one knott in their rugs wrong on purpose. The idea being only God was allowed to be perfect. There is an inherent beauty in something that has room for improvement. People for example.

Your foresight proved right. And this is why the artists and humanists will save us from AI. Original human creativity is the supply it needs the most to survive. 🤖 🎶