My Lost Gumby Essay

Or how I overcame ontological horror with the help of a rubbery toy

“It is more important in life to lose than acquire.”

Boris Pasternak

I’ve lost so much of what I wrote in my early days. But that’s a blessing in disguise. Much of it was strange and unlikely to please any editor—or please me nowadays, in my sober and mature years.

The larger truth is that I was an unusual dude at age 20. Sure, I’m still an odd duck in most ponds. But my eccentricities have softened over time. Back then I was more bohemian than Prague City Hall.

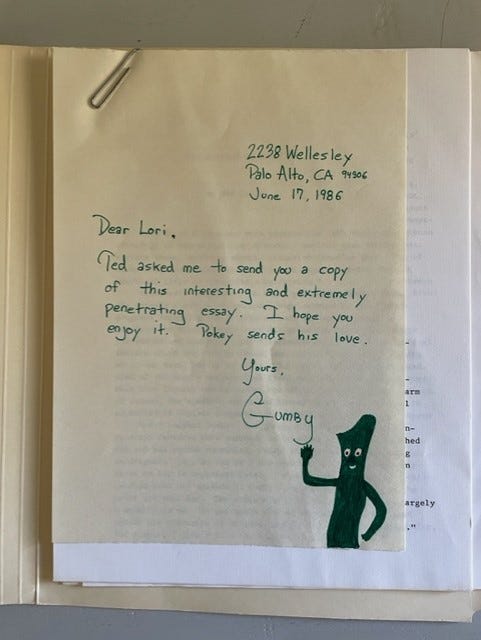

So I was both fascinated and fearful when an old friend discovered a photocopy of a philosophical essay I wrote in my 20s about Gumby, the clay animation TV character from my childhood.

Gumby (and his sidekick Pokey) were pretty bohemian too—and more than a little creepy. But Gumby was also a genuine brand franchise, spun-off in rubbery dolls, lunch boxes, and various toys.

For some unknown (probably Freudian) reason, I bought a Gumby doll in my twenties, and started bringing it with me to various meetings and locales. I pursued this as a type of existential experiment.

I observed Gumby’s impact on people and situations. And I gradually formulated a theory of Gumby. This, of course, demanded an essay—which shared the results of my inquiry into Gumby-ness.

I knew it was an outlandish essay, even back then. But I told myself that it was exactly the kind of thing Husserl (a real native Bohemian) might have written if he’d resigned from the University of Freiburg to take a job at Toys R Us.

My friend recently rediscovered this essay, and sent it to me. (I had destroyed or discarded my own copies.) I’ve decided to publish it here—as a bit of a curio.

If you lack an appetite for bizarre cultural criticism, you are advised to stop reading at this point.

But I share this writing here, despite its eccentricities and blemishes, for good reasons.

The most redeeming feature of my lost Gumby essay is that it testifies to my willingness to take chances as a writer, even at that young age. Believe it or not, I actually thought this could be published back then.

Even more surprising, a famous magazine almost accepted my Gumby essay. But the editors eventually decided (no doubt wisely) that it was too outre for their readers.

So it was a pipe dream but still a good thing—this mindset encouraged me to think differently and put my faith in risky projects. The Gumby essay below was also a stepping stone in learning how to make serious points in extravagant, unconventional, or semi-comic ways—which is still a useful technique for all writers who aim to persuade or please.

With that proviso, I share my lost Gumby essay. I’ve cleaned it up a bit, but present it largely as it was written back then.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

My Lost Gumby Essay

or How I Overcame Ontological Horror with the Help of a Rubbery Toy

By Ted Gioia

As a child, I devoured indiscriminately the full range of TV network offerings—movies, game shows, sporting events, sitcoms, variety shows, and above all, the various programs lumped together under the catch-all title of children’s television.

Children’s TV in those pre-Sesame Street days, was largely a matter of cartoons, supplemented by occasional programs featuring ‘real’ figures such as Captain Kangaroo and Bozo the Clown. They were all grist for the mill of my pre-adolescent curiosity.

Like all children, I projected myself into the story. I asked: Could I grow up to be a Captain of kangaroos? Would I be a Bozo some day

I followed these protagonists with a rapt attention that few circumstances, and certainly no TV show, evoke in me today. But there was another kind of children’s program back then, featuring neither live figures nor cartoons. This alternative hero defied the moral authority of Captain Kangaroo and rose above both the Hobbesian anarcho-capitalism of Looney Tunes and the Rousseau-esque innocence of Disney.

I’m talking about Gumby.

How I loathed Gumby!

His gooey, fluid movements and non-descript features were anathema to my young mind. I watched him and his equine companion, Pokey, with something bordering on Sartrean nausea.

Yet, as far as I can recall, my reaction drew on little empirical data. I can’t remember watching even one episode of Gumby from start to finish. I never got that far. The content of the show is still largely a mystery to me.

It was Gumby himself who disturbed me—and not by his character or actions, but by his very Gumby-ness. Put simply, I didn’t like the looks of him.

Was it possible that I might grow up to be a Gumby myself? I rejected that notion with all the force I could summon in my 5-year-old soul.

“Towards the end of Jean-Paul Sartre’s monumental work Being and Nothingness, he reflects that viscous substance have the rare effect of both attracting us and disgusting us at the same time.”

I had few scruples about the other television shows I watched. Violence in children’s programs—then an issue in the news—did not upset me. If anything, witnessing brutal punishment meted out to the likes of Elmer Fudd and Wile E. Coyote both nurtured my latent sense of justice and fair play, as well as provided me with intense Aristotelian katharsis.

During the free hours not devoted to TV, I played cops-and-robbers and various other imaginative games of retribution and schadenfreude—senseless and violent, but not much different from what the politicians and other grown-ups were doing in their distant worlds. My collection of toy guns amounted to something of a plastic arsenal, stored in a cupboard between assorted games named after various forms of destiny (Risk, Chance, Monopoly, Sorry, Life, etc.) and my growing collection of comic books and bubble gum cards.

There was, however, no Gumby among my toys.

I would have even preferred another Slinky—that would have made a total of five in my possession (all unwanted gifts from birthdays and holidays, still unused in the box). Or something infantile, even to my young untrained mind, like a Mr. Potato Head. Having a Gumby was like having kooties—the fewer, the better. And none best of all.

As time passed, my visceral abhorrence of Gumby gave way to benign neglect. I was becoming an adult, and the concerns of childhood were replaced by other, more pressing cares.

When I next encountered Gumby—more than a decade later—it was with transformed feelings. While walking on the UCLA campus, I encountered a young guy dressed up, for inexplicable reasons, in a life-size Gumby outfit.

Such a sight was impossible to ignore. The costume was amazingly real-to-life, and it exuded that distinctive industrial greenness so unique that it ought to be called Gumby Green.

I was amused by this Gumby impersonator. But—and this is the strange part—I positively envied him. I wished I had a Gumby costume just like his. Where could I procure one?

I had gone from Gumby-phobia to Gumby-philia in an instant.

All this would hardly be worth recounting, except for my suspicion that a more general philosophical truth lay behind my epiphany in Westwood. In short, I grasped that Gumby provided an existential touchstone, and not just for me. My hunch was that Gumby could be a pathway for others.

Test this idea yourself.

Raise the subject of Gumby during a casual conversation. Okay, that’s not always easy to do—so bring a toy Gumby with you to various events.

Then watch how people react.

Gumby will evoke powerful feelings—both positive and negative—in everybody he encounters. Some people will grab your Gumby and caress him lovingly. Others will sneer and mock. But nobody will be indifferent.

This is simply not the case with other figures of children’s TV. Bugs Bunny, Mickey Mouse, Mister Rogers, all three Stooges—these we may like or dislike, tolerate or dismiss, but none reaches as deeply into our psyches as Gumby.

But why?

The key to solving the mystery of the Gumby Syndrome (I’m going to become renowned for naming it thus) can be found in the writings of French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Towards the end of Sartre’s monumental work Being and Nothingness, he reflects that viscous substance have the rare effect of both attracting us and disgusting us at the same time.

Mud, glue, and all the various types of goo and stickum which we encounter day to day are often things we openly despise, but with an undercurrent of fascination.

And if you combine them, all hell breaks loose. Place a Gumby next to a plate of oysters, and diners will start a riot. Half will run to the doors, while the other half come with fork, knife and open mouth.

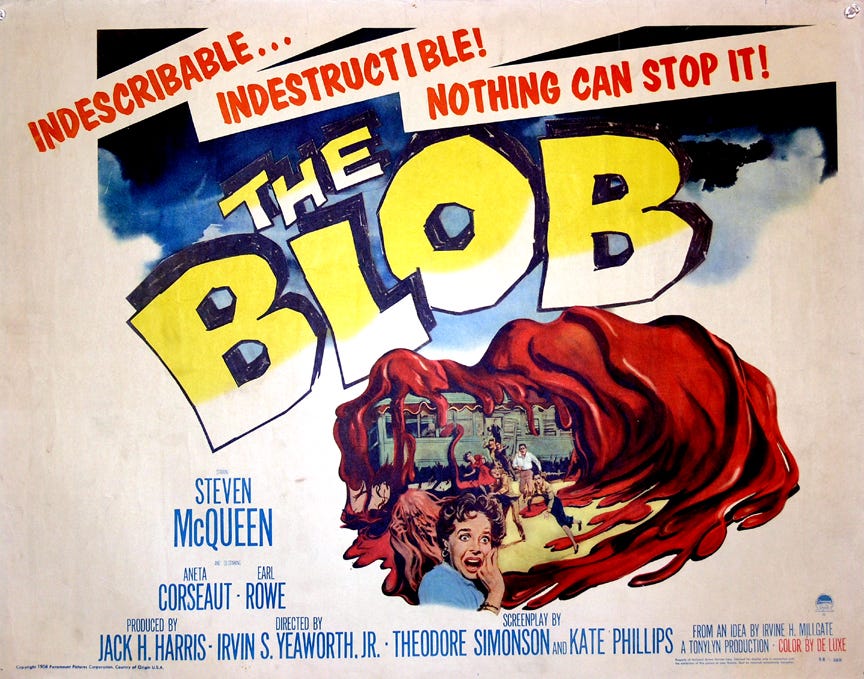

Children instinctively feel this even more than adults (who block out such primal feelings). Hence the mud pies and Silly Putty of youth. That’s why a movie like The Blob, with its depiction of formless, pulsating eco-matter on the loose, is bound to be a hit with the kids. But even grown-ups can’t totally escape the Blob’s disgust/attract magnetism.

You see the same thing in foods that children find fascinating—Jell-O, bubble gum, or peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. The appeal is driven by texture and quiddity, not taste.

Many are the things we graciously give up with the passing of youth—including most of the viscous substances discussed above. We often come to abhor the same gooey victuals we loved as children.

This dialectical shift from attraction to disgust in the face of blob-like substances can serve as a narrative device in stories. At one point in a Raymond Carver tale, a couple driving to a friend’s house for dinner speculate on all the things that could go wrong during the coming meal. “What if they serve Jell-O for dessert?” the wife asks despairingly. The prospect fills them with vague alarm.

Carver demonstrates here the same equivocal response to the viscous (“le visqueux,” rendered somewhat disappointingly as “the slimy” in the standard English translation of Being and Nothingness) as his Parisian predecessor. Cartesians, for their part, may see in this ambiguous response a conflict between our spiritual essence, which is repulsed by the pure materiality of formless matter, and our physical essence. These dualists invariably reject any Gumby-like reduction of personhood to soulless rubbery matter.

Issues of personal psychology may also intervene here. I note that Sartre possessed a Gumby-ish face and figure. I’m tempted to speculate on how such individual traits may influence a thinker’s worldview. But that’s beyond our scope here.

Other thinkers of a Derridean postmodern tenor may embrace this ambiguity. They celebrate the différance embodied in substances crossing boundaries between solids and liquids, form and content. In any event, the result is the same—a notion of Gumby (and Pokey too) as a touchstone, a way of comparing different ways of conceptualizing existence.

My own experiences with Gumby, however, were the exact opposite of what you might expect. Rather than losing any child-like fascination with the viscous, I only gained it on the brink of adulthood. Not many grown-ups react this way. I can’t imagine Gumby surviving in prime time—he flourishes amid the prepubescent audience of Saturday morning television. That is his natural constituency.

But Gumbyphobic grown-ups have little to be proud of. Their reaction to this Claymation pioneer shows clear signs of repression. My own armchair psychoanalysis substantiates this theory. During the course of many Gumby experiments, I have noticed the more neurotic, the more jaded, the more stuck-up the individual, the less receptive he or she is to that gentle green protagonist.

But those rarely encountered children in adult form, the perpetually young-at-heart, will usually approach Gumby with veritable glee. May we all retain such childish delight in our mature years.

“I was once involved in intense negotiations with Japanese businessmen, and needed to find a power play to intimidate these tough bargainers….”

Gumby has even provided me with a guide to action in uncertain situations. That’s why I keep a Gumby on my desk, and advise others to do the same.

Almost everyone who comes near your Gumby will comment on it. So it’s worth having Gumby on hand if only for his utility as an ice-breaker and for the proverbial ‘lull in conversation.’ But even more important is the way Gumby discloses each person’s inner truth.

A stranger comes into your presence, and shows clear signs of enjoying Gumby. Even picks Gumby up and plays with him. That’s a person you can trust—this individual is free from ontological horror and comfortable with the organic basis of reality. But those who reject your Gumby, who move away or make disparaging comments—the less you have to do with them the better.

Of course, Gumby is not suitable for all situations—but there are viscous substitutes that work in a pinch. I was once involved in intense negotiations with Japanese businessmen, and needed to find a power play to intimidate these tough bargainers. I asked around—seeking some way I could assert myself in these tense Tokyo meetings.

I sought advice from a friend who had lived many years in Japan. “I know exactly what you need to do,” my buddy replied. “Here’s something that will make them fear you. At the start of the meeting, offer each one (as a gift—they can’t refuse, hah!) a big hunk of black licorice. I know for a fact that the Japanese will almost faint at the prospect—they find the texture and appearance totally disgusting.

“You just need to insist that they taste it immediately, before the meeting begins. You will have them on the run from that moment on.”

That’s the power of viscous substances, my friends. Gumby is merely their archetype and heroic embodiment.

I am told, by those who follow such things, that Gumby is undergoing a revival nowadays. I even read in a magazine that “the signs of a Gumby renaissance are everywhere and unmistakable.” I must admit that, in my current state of mass media deprivation, I’d been largely unaware of this exciting development.

But now that the Gumby renaissance has been brought to my attention, I can only applaud wholeheartedly and hope that post-adolescents everywhere will join the movement.

There are many in our midst who would do well to rediscover the charms of Gumby. He is our surest pathway to escaping existential agnst. And by opening ourselves up to him, we also open ourselves to that child, still full of wonder and untarnished by the passing years, who lies latent in all of us. And a rubbery toy is a lot cheaper than therapy.

1.) Gumby, Silly Putty, Play-Doh, Slinky... I loved them all. I had a strong aversion to plastic though. Refused to put my mouth on anything plastic and refused to eat with plastic utensils.

2.) Dude, how could you not play with your slinky? If you start it out just right, you can get a slinky to walk down an entire flight of stairs. It's amazing.

3.) If you had played with Gumby as a child, you would know that eventually (if you spend enough time bending it into different poses) the metal wires inside that allow it to retain a pose will pop through the rubber giving a young child an early lesson in aging and mortality. And also, you have to find new meaning and ways to play with the broken down disfigured formerly perfect Gumby.

4.) One of the most frustrating aspects of Gumby is that the natural desire to have Gumby ride Pokey is thoroughly thwarted by the fact that Gumby's crotch is triangular and Pokey's back is square. It's just impossible.

5.) I now want to obtain a Gumby.

6.) You could vary your experiment by only carrying around a Pokey.

I love seeing animated cartoons used as jumping off points for discussing philosophy!