My Afternoons with the Singing Bowl Lady

I'm not a New Age guy, not even close. But I keep returning to these singing bowl sessions

After all these years, I thought I’d heard every kind of music. And then, I met the Singing Bowl Lady.

That’s actually what it says on her door: Singing Bowl Lady.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I live in a city that brags about its weirdness. So why shouldn’t there be a Singing Bowl Lady in my neighborhood? She makes those bowls sing in a little retreat upstairs from a donut shop and next to a local contractor. She also freelances in other places around town—and even makes house calls.

I call this music, but that word hardly captures the experience of hearing her bowls sing. Let me put it another way: When the sounds begin, I’m not just listening to the music—instead I actually become the music.

At least that’s how it feels.

I know all this sounds too New Age-ish for many of you. In my defense, I will say that I don’t rely on any alternative form of medical intervention—I’ve never even visited a chiropractor, acupuncturist, hypnotist, or even a massage therapist.

I just visit the doctor, and that as rarely as possible.

My ignorance of these things is extreme. I can’t point to my chakras, and am not sure if they are the same as reiki, or something completely different. I couldn’t tell you the difference between an enneagram and a planogram. I haven’t even had my fortune told, unless that little piece of paper in the cookie counts.

The bottom line is that the closest I get to alternative treatment is a few bottles of vitamins and supplements—and even those usually reach the expiration date on the label before I finish the bottle.

So I am not a New Age kind of guy.

But I make an exception for the Singing Bowl Lady. And it’s all because of what I learned while writing my book Healing Songs, which I published back in 2006 (more on that below).

Healing Songs wasn’t a very New Age kind of book either. It actually survived peer review, and got published by a legit academic press—back in the days when I worried about such things. When I started writing it, I was a total agnostic about the healing power of music. I really didn’t have an opinion one way or the other. I was merely a music historian who wanted to document what others did.

Even so, writing that book shook me up. It forced me to consider different capacities of music and sound, far beyond any I’d previously grasped. By the time I finished writing it, my whole conception of music had expanded considerably.

I even acquired a singing bowl of my own, but just a small one. I keep it near me while I work.

But until I met the Singing Bowl Lady, I had never experienced what it sounded like when a skilled practitioner worked the big bowls.

Reward your nearest and dearest with a gift subscription to The Honest Broker this holiday season.

I’ve been immersed in music my whole life, but still had never actually felt such huge sounds pulsating throughout my entire body—an experience almost as tangible as it is auditory. Even the most intense live music events hadn’t prepared me for that kind of music.

Just because we can’t see sound, we tend to minimize its power—but that’s a big mistake. There’s a reason why doctors use ultrasound to break up kidney stones and cataracts. At my last visit to the dentist, the hygienist told me she was using ultrasound to clean my teeth. Just this week, I read about a program to treat Alzheimer’s with ultrasound.

These things are happening everywhere—and not just at the Singing Bowl Lady’s sessions.

Sound is power. That’s been a major thrust of my work over the last three decades, but even I continue to be surprised by the full implications of this simple statement. Researchers at UCLA are actually using ultrasound to wake people out of comas—including one case in which a man had been in a minimally conscious state for 14 months.

They brought him back to life with a small sound-emitting device that looks like a saucer in your kitchen cabinet.

As you probably know, my new book—which I’m publishing in installments on Substack—is called Music to Raise the Dead. What they’re doing at UCLA comes pretty close to that.

I call these musical instruments. And why not? That’s exactly what they are, by my measure: instruments channeling organized sound to produce a change on the hearer.

The singing bowls are much like that. When I visit the Singing Bowl Lady, my whole body feels like it’s a vibrating string in a musical performance. No concert or recording has ever given me that same feeling—not even close.

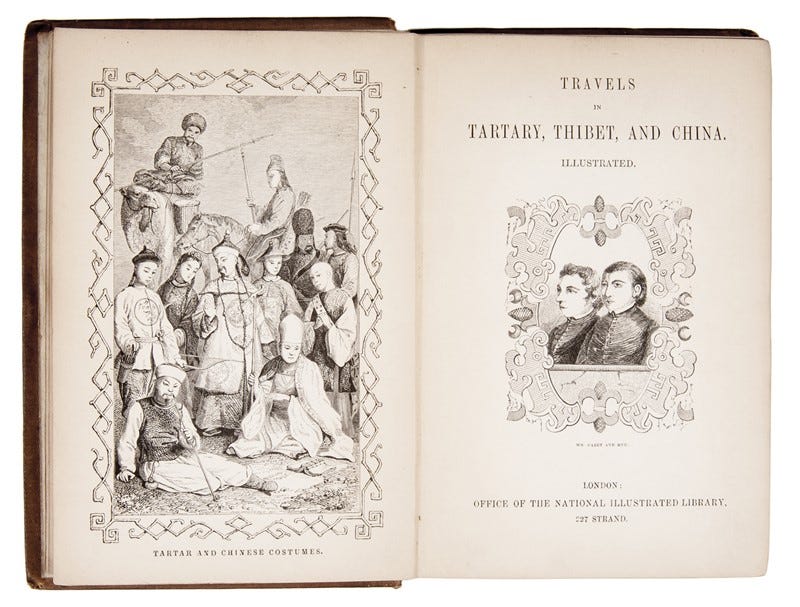

Back when I was writing my Healing Songs book, I became frustrated over how little had been published about singing bowls. They are often described as Tibetan in origin, but I searched through various primary sources in vain for more details—even going back to the narrative of the great Tibetan yogi Milarepa from the twelfth century. That’s a fascinating case study, but the bowls aren’t mentioned at all in it.

I got more information from Perceval Landon, a traveler to Tibet in 1902-03,. He explained that “the Tibetans have not reached the stage at which noise ceases to be the first aim of the musician. By this I do not necessarily mean that the noise is always an ugly one.” That’s not much to go on, but the concept of a pleasant noise is compatible with the experience of hearing the bowls singing with all their power.

An even older description came from 19th century missionaries Evariste-Regis Huc and Joseph Gabet, who described a ‘doctor-in-chief” who cured the sick with “cymbals, sea-shells, bells, tambourines, and other instruments.” This too is fairly vague, but I note that the singing bowls can produce a bell-like tone, and would fit in with these other sources of musical vibration.

But the single most useful source for the account in my Healing Songs book was an amateur researcher named Frank Perry. He had examined more than 4,500 singing bowls and classified them into 45 different types.

But even Perry had little information on the origin of the singing bowl tradition. He noted, however, the widespread belief in their healing properties. He also commented on the growing reliance on bowls made of crystal rather than metal.

The Singing Bowl Lady—who also goes by the name of Sandee Conroy—relies on both metal and crystal bowls, but especially the latter. She works surrounded by five or more enormous crystal bowls. They look like bass drums turned on their sides.

Each is tuned to a different frequency, and the large size allows for a very low penetrating sound. But even the concept of tuning is a loose one here—I was amazed at the range of bending and fluctuating tones that could be produced by even a single bowl. After our last session I asked her demonstrate how she did this, and if I hadn’t seen it firsthand, I wouldn’t have believed what I heard.

I can’t really convey in words what it feels like to be enveloped in this sound—it must be experienced firsthand. But I will share a few specific experiences.

I thought I would use my hour sessions with the bowls to meditate, but I found myself so overwhelmed by the experience of vibrations spreading through my body that I couldn’t really focus on anything except the moment-to-moment visceral feeling. Even in the most flow-inducing moments of performing jazz on stage, I’ve never felt so intensely that I had become the music itself.

Sandee warns people up front that she plays the bowls with great intensity, and even offers ear plugs for those concerned about the volume. I was apprehensive when I heard this—I tend to dislike very loud music, and have even walked out of concerts for that reason. But I found that the volume of the singing bowls is something very different. Because the power is channeled into my body, I welcomed the intensity. It feels invigorating and energizing. I wouldn’t want it any less intense.

Some of my experiences during these sessions seem to defy logic or common sense. One of the most striking is the moment when the vibration moves back in forth from different parts of my body in a set rhythm. The most typical situation is when the vibrations start moving back and forth between my right ear and left ear at predictable five-second intervals. If I didn’t know better I would think the source of the sound was moving back and forth across the room, but that obviously isn’t happening. I’ve found that this experience occurs no matter where I am located in relation to the bowls.

In other instances, the music seems to move back and forth from my ears to my neck, or from leg to leg, or in some other pattern, but always with a marked and repeated rhythmic pulse.

Sandee says that some people feel that the sound is located in the precise part of their body where they were recently injured, or had an operation, or find otherwise sensitive. I didn’t experience this, but I can easily believe it. It’s obvious that the vibrations penetrate every part of your body, so I’m hardly surprised that someone would feel it centered on the limb or organ they worry most about.

About 20 minutes into a session, something surprising happens to my breathing. All of a sudden I will feel an extraordinary expansion in my lung capacity. The subjective feeling is that I’ve never breathed this deeply before. I even tried an experiment, using a meditation technique I follow at home, where I count while inhaling. At home I find that I typically count to 4 before my lungs feel full, although sometimes I get up to 6 or 7. I tried replicating this while experiencing the singing bowls, and discovered I could easily count up to 10, with no strain. In fact, I felt that I could inhale even more than that if I wanted. This is a very liberating sensation, although I would have never guessed that something as basic as breathing could have a dimension previously hidden from me.

This leads to the single most predominant sensation I have during and after a singing bowl session, namely the feeling that every part of my body, internal or external, has been flexed, loosened, made more limber, comfortably stretched. I am reminded again of those ultrasound tools that break up kidney stones or cataracts. As strange as it sounds, I could easily imagine athletes using the sound of these bowls to deal with tight muscles, pinched nerves, or rehab of various sorts.

Sandee typically relies on a kind of wand—a cross between a conductor’s baton and a two-headed mallet. The center is wood, but one end is rubber and the other suede. By moving these in different ways around the periphery of the bowl, the sound goes through a rainbow of different textures, gradations, and other aural colorings.

I share a video link with some reluctance—because a recording absolutely fails to convey the firsthand experience. But for educational purposes, this film clip does demonstrate the specific techniques involved in playing a bowl.

Sandee told me that the bowls usually produce the sounds she wants, but even after all these years they still can surprise her with unexpected responses. She specifically compared this to a jazz improvisation. “I used to get upset at this,” she explained, “but I’ve learned to work with it, adapting to the sound the bowl wants to make.”

I like that analogy to jazz. It feels right, too. Playing jazz is an immersion into the immediacy of the moment. The singing bowls are like that too. But there’s one big difference—it took me years to tap into the genuine power of playing jazz. But the bowls hit me with full force on the first encounter.

I’ve already said too much. The words don’t capture the experience, so I really ought to opt for Wittgensteinian silence. That’s because you need to feel those bowls up close and personal. And maybe, if your city is weird enough, there’s a singing bowl lady—or singing bowl dude, or whatever—near you. If so, make their acquaintance.

Great article. One very off track comment, pursuant to this: "I was apprehensive when I heard this—I tend to dislike very loud music, and have even walked out of concerts for that reason." I like Mark Knopfler for his songs and his guitar playing, but I also admire him for what I read about when his band Dire Straits was getting started and people in small venues kept on telling the band to play louder. Knopfler woudn't let them ... consequently decades later, Knopfler still has his hearing while many rock musicians, even some much younger than him, don't.

Wish I had a crystal singing bowl, have several metal ones.

Could it be that these bowls and similar instruments such as bells, have partials that are not always harmonic, and that adds to the interest and strangeness to Westerners? Orchestral instruments have primarily harmonic partials, and as such seem more cerebral, rational, and linear to me. (Don't get me wrong, I love symphonic music!)

Wish I could be there, or had heard La Monte Young's Just intonation experiences . . . one of the reasons "samples" don't work is not due to the sound itself, but the fact that most MIDI instruments that play them are stuck on the equi-tempered scale . . . "temperament" may be a lost art, and perhaps is of greater importance than we imagine nowadays.