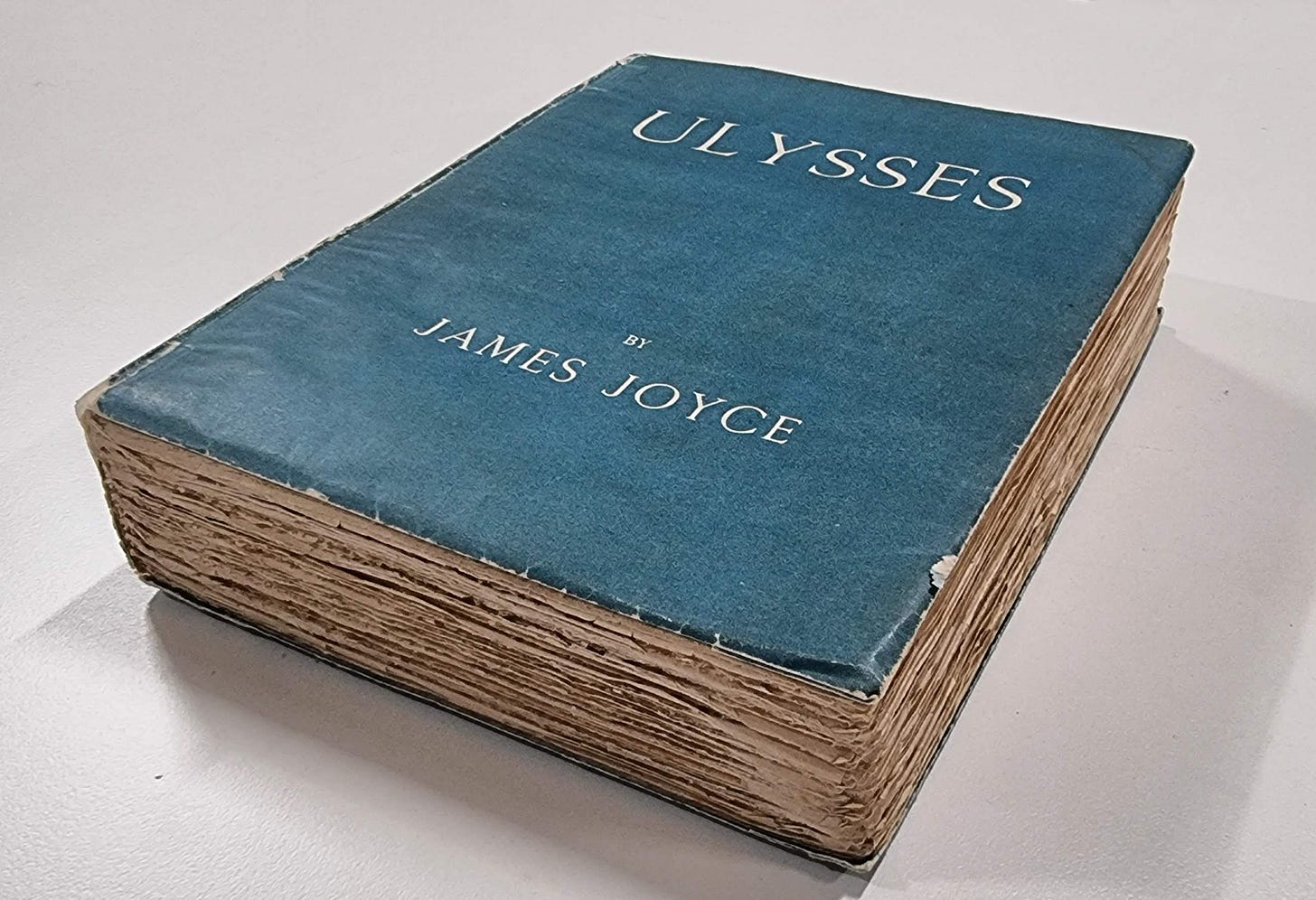

James Joyce's Ulysses Turns 100 Years Old Today

This famous novel takes place over the course of a single day, but James Joyce needed two decades to write and publish it

Housekeeping: I want to welcome the many new members of our community—thousands have joined our ranks in the last week. Much of this is due to interest generated by the article on “old music replacing new music,” which set a record for ‘clicks’ (ugh, what an unfortunate term) at The Honest Broker.

Yesterday, I spent an hour with Krys Boyd on NPR talking about the reasons why the music business is focusing so much on old songs, and what this means for younger musicians and our culture. Here’s a link to that interview.

I ought to forewarn new subscribers that we cover a lot of ground here. Today I’m making a rare visit to my archives—because this is the 100th anniversary of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Many people will tell you that Ulysses is the greatest novel of the last century, and even those who disagree will often acknowledge it as the most influential or, at least, the most difficult.

We could argue about those claims endlessly. But there’s a fascinating story behind this book.

So today’s centenary is a good occasion to revisit my account of how James Joyce created such an iconoclastic work—devoting two decades to putting down on paper a 350,000-word story that elapses over the course of a single day.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

How James Joyce Made Ulysses

by Ted Gioia

James Joyce’s father once commented about his son: "If that fellow was dropped in the middle of the Sahara, he'd sit, be God, and make a map of it."

In this rumination on the Joycean mindset, John Joyce wasn't talking about the novel Ulysses—he had few words of praise for that book. But he might very well have been describing the process that led to his son writing it—because, for all its complexities, Joyce’s novel is very much like a map or a traveler’s itinerary.

And the senior Joyce may have played a part in this aspect of his son’s famous book. He shared James's interest in the byways and notable locales of the city, and perhaps even inspired it with their shared walks, during which John Joyce pointed out Dublin's literary landmarks—the home of Jonathan Swift, the birthplace of Oscar Wilde, the places where Joseph Addison had strolled before them, and other such locales of interest.

But nowadays anyone looking at a literary map of Dublin will see that it has been rewritten since that time, and mostly by James Joyce himself, whose great novel involves a stroll around the city. Many of the author's admirers try to follow along in its footsteps, often on June 16—the date on which Ulysses takes place (picked by Joyce because this was the day of his first date with his future wife Nora)—but on other occasions as well. Even in his lifetime, Joyce celebrated this anniversary, and heard from readers of Ulysses who also commemorated Bloomsday, as it has come to be called.

In the mid-1950s, Bloomsday showed the first signs of turning into a kind of Dublin-based Mardi Gras, with a recreation of Leopold Bloom’s stroll, in period costume, starting from the character's home on Eccles Street, and following a route that included O'Connell Street, Parnell Square and the Martello Tower. But like St. Patrick’s Day, Bloomsday has spread beyond Ireland, turning into a celebration in which everyone gets to be Irish for 24 hours. The event is now commemorated in at least 60 countries, as well as virtually on the web.

A real life stroll that Joyce took in 1904—not on Bloomsday, but four days later on June 20—may have served as the initial spur that led to Joyce's later writing of Ulysses. Well, not really a stroll, more like a stumble. For this author, so fascinated by fallen characters—Humpty Dumpty, Adam, and Finnegan all show up in his books—came to his most famous work via a couple of falls of his own.

Joyce was often chided about his drinking by his brother Stanislaus, who feared that alcohol would destroy his sibling’s considerable talent. On that June evening, Joyce had so much to drink that he first caused a scene at the premises of the Irish Literary Theater, where he collapsed on the floor near the entrance, and others had to step over the promising young author, sprawled in his own vomit. But Joyce had another fall in store for him before the night was over, even more painful than the first.

After rising from this first stupor, he got into an altercation with a soldier. Joyce was badly bruised in the encounter—his later thumbnail summary was: "black eye, sprained wrist, sprained ankle, cut chin, cut hand"—but the future author of Ulysses was rescued that evening by a person who was almost a complete stranger. Alfred H. Hunter, a slight acquaintance of Joyce's father, found the young writer in some distress, and brought him back to his own home to sober up and recover from his wounds.

Joyce was impressed by Hunter’s unexpected intercession, and also by the character of the man who had played the role of Good Samaritan. Hunter was Jewish and allegedly a cuckold—in both ways a prototype for Leopold Bloom—and the incident planted a seed that would later 'bloom' into Ulysses. Two years later, on September 30, 1906, Joyce sent a letter to his brother in which he announced that he was planning on turning this encounter into a story, probably a short work akin to those he had already written for Dubliners. In another letter, from November 13, he mentions the idea again, and now it has a name: "I thought of beginning my story 'Ulysses', but I have too many cares at present."

“Even after it was published, could Ulysses be distributed without customs agents seizing and burning the books? And if it made its way into a bookstore, could it be sold without drawing a response form police and prosecutors?”

Clearly the connection with Homer's Odyssey was already in Joyce’s mind. And if Hunter would turn into Bloom, who would represent Ulysses, Joyce already had a real individual and fictional character slated for the part of Telemachus, Ulysses's son: the author himself and his literary alter ego Stephen Dedalus. By November 1907, Joyce had changed his mind of the scope of the work, and now began describing it as a novel. His brother Stanislaus writes in his diary on November 10: "Jim told me that he is going to expand his story 'Ulysses' into a short book and make Dublin a 'Peer Gynt' of it….As it happens in one day, I suggested that he should make a comedy of it, but he won't."

Related Essays:

How James Joyce Almost Became a Famous Singer

The Many Lives of James Joyce

Revisiting James Joyce's Dubliners

The Finnegans Wake Toolkit

Even though Joyce, as these comments make clear, had already decided, at this early stage, to embrace the Aristotelian unity of time—which limits the span of events in a story to 24 hours—his ambition to create a Dublin-based equivalent of Homer's Odyssey demanded a much larger scope than any he had previously attempted. On June 16, 1915 he told his brother that he envisioned 22 episodes in his Ulysses, but by May 1918 he had scaled back his plans and promised his patron Harriet Weaver that there would be seventeen. The finished work had eighteen episodes, and amounted to a massive 350,000 word novel—more than twice as long as Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man combined.

Yet almost every detail, incident and character in this sprawling book was first experienced by Joyce himself or collected from the real-world accounts of others before getting processed and transformed into the form of fiction. Sometimes the connections are complex—at least a half-dozen different women contributed in some degree to the character Molly Bloom—but the various lineages invariably link back to actual people and circumstances. Joyce may have gained fame as the writer who pushed fiction the furthest in modern times, but in another way he can be seen as the author who took the fewest liberties with his subject. He did not create ex nihilo but rather ex materia.

Even the character in Ulysses who seems to occupy the opposite end of the spectrum from Joyce / Dedalus, namely Leopold Bloom, also reflects aspects of the author, or at least his idealized image of himself. The high profile of a Jewish protagonist in the great Dublin novel is neither a departure from the book's Irishness nor a detour from the autobiographical essence of the work. Joyce saw himself as an exile from Ireland, both rooted in his homeland and at odds with it—an attitude that made him especially sympathetic to the plight of Irish Jews. (In Finnegans Wake, the hero appears to be a Protestant, so the contrast with the pervasive Catholicism of Ireland is echoed in the later book too.)

But this convergence was more than a matter of Joyce's psychological leanings. The era during which our author came of age was a time of Irish diaspora. Already in 1890, when Joyce was just eight years old, two out of every five persons of Irish descent in the world were living outside of Ireland, and the exodus continued non-stop for decades to come. True, the Irish—unlike the Jews at the time—possessed a homeland; but even at home, the Irish lacked sovereignty. The country would not gain independence from Britain until 1922. Joyce often commented on the similarities between the Irish and Jewish temperament, but just the brute facts of history supported his insight that Leopold Bloom of Hungarian-Jewish ancestry, could serve as a suitable emblem both for an ambitious Irish author and his long-suffering fellow Dubliners.

Joyce thus had two levels of meaning with which to launch his grand novel, a personal, autobiographical one and a Homeric epic one. And he also saw each of these stories as representing a larger cultural history—drawing on parallels between Irish and Jewish destinies. But in time, other levels of signification were woven into the book. Each chapter, as he saw it, could 'embody' a different organ of the body. But he also wanted to use the book to showcase a litany of different ways of writing. Joyce later defined "the task I set myself" as "writing a book from eighteen different points of view and in as many styles, all apparently unknown or undiscovered by my fellow tradesmen." The end result was a novel that infuriated many, amazed others, but—love it or hate it—stands out as one of the most ambitious projects in the history of literature.

The construction of this book, for all its challenges, was only a prelude to more obstacles to come. Finding a publisher posed a different set of problems. And the publisher needed to find a printer who was not afraid of criminal prosecution, given the book's content and the obscenity laws of the days. Even after it was published, could it be distributed without customs agents seizing and burning the books? And if it made its way into a bookstore, could it be sold without drawing a response form police and prosecutors? At every step of the way, Joyce faced potential stumbling blocks.

Thus James Joyce had his own perilous odyssey ahead of him, and his project took almost as long as Ulysses's own in the Homeric epics to complete. Homer tells us that Odysseus spent ten years fighting the Trojan War and another ten years in his much delayed journey home. For Joyce, the timetable is even more protracted. Ten years elapsed between the 1904 events that inspired the book and the commencement of its writing. Eight more years transpired before Ulysses was published by Sylvia Beach in Paris. Joyce needed to wait another eleven years before the court decision that allowed sale of the book in the United States. Almost thirty years after Bloomsday, in January 1934, the first US edition was released. The first UK edition did not come out until 1936.

In fact, someone could write a book about the making of Ulysses, and base it on the Odyssey as well. We have all the ingredients here—angry rivals at home in Ithaca (or Dublin, in the case of Joyce), and foes and obstacles in other farflung settings, everything conspiring to prevent the protagonist from fulfilling his destiny.

But achieve it he did. Along the way, Mr. Joyce proved—in more ways than one—to be the hero of his own story. This was the one layer to Ulysses that Joyce never intended to add. It was forced upon him by circumstances, most of them arising after the book was written. But I can’t help but find it fitting and proper that, in an age in which art became increasingly self-referential, the most avant-garde of novels proved so maddeningly true-to-life.

This essay originally appeared in a slightly different form on the Fractious Fiction website.

It's noteworthy that Joyce spent several years in Trieste, Italy

Maybe the greatest book almost no one has ever finished ...