Jack Kerouac at 100: Part 2 (of 2)

I reassess the King of the Beats with both hope and trepidation—asking whether his work can still speak to us today

Below is the second (and final) installment of my look at Jack Kerouac on the occasion of his centenary. You can find part one here.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Jack Kerouac at 100, Part 2 (of 2)

By Ted Gioia

III.

In late 1945, Kerouac began working on a big book, entitled The Town and the City. The scope would have been impressive for any writer at age 23, but especially for Kerouac, previously incapable of completing his ever-changing projects. He wrote 1,183 pages during marathon sessions at his desk—much of it eliminated by the time Harcourt Brace finally released this debut novel in February 1950.

This work is more controlled than Kerouac’s later novels, but the basic formula would never change for him. His books were all drawn from life—in fact, Kerouac never wrote purely from imagination in any of his novels, and when he stopped having road adventures with his buddies, during his final years, his creative juices dried up completely. So it’s fitting that, in his first book, Kerouac simply took himself and all his friends, and presented them as characters in a story. Allen Ginsberg became Leon Levinsky. William Burroughs showed up as Will Dennison. Lucien Carr got turned into Kenneth Wood. The main character, Peter Martin, is Kerouac himself. Elsewhere the reader encounters Kerouac’s parents and many of his casual acquaintances in slightly disguised form.

Writers had previously drawn upon their own experiences as ingredients for their fiction, but Kerouac would soon be pushing this to an extreme. In a different age, he would have been a grand diarist, in the tradition of Samuel Pepys or James Boswell. But he had the insight to grasp that his generation was living through a cultural shift that needed to be translated into stories—and that he could do this by turning the incidents of his life, both large and small, into fictional narratives.

“‘You’re a character in a Kerouac novel?’ I asked in amazement. I couldn’t have been more dazzled if he had told me he had committed the Lufthansa heist or slept with Doris Day.”

This was made strikingly clear when the original “scroll version” of Kerouac’s breakout novel On the Road was published in 2007. Here the fictional characters’ names were gone—Dean Moriarty is simply called Neal Cassady, the real life inspiration for the protagonist. Carlo Marx now becomes Allen Ginsberg. And other real people take over their previously fictional roles. When the New York Times reviewed this original version of the novel in August 2007, Luc Sante admitted that “the scroll is essentially nonfiction, a memoir that uses real names.”

Just consider: If Kerouac had retained these real-life identities in the first edition of On the Road, it might now be considered as the prototype of the non-fiction novel. How ironic that much of the credit for legitimizing that innovation is now assigned to Truman Capote, who used it to great effect with In Cold Blood in 1966. Capote was one of Kerouac’s harshest critics, but in this instance, the King of the Beats anticipated him by a decade.

When On the Road was published, even in its disguised form with roman á clef characters, readers could feel the blurry line between art and reality—and welcomed it as an entry point into a new way of existing. That was actually the covenant implicit in the beatnik aesthetic: If you hung out with people like this, your own life could become a work of art.

That actually happened to my friend Paul Smith, a lovely person and bassist who was once a member of my jazz quartet. As a young man, he spent time with Jack Kerouac and other Beats—and then found he got turned into a character in the Kerouac novel Big Sur.

When he first told me this, between sets on the gig one night, I was awestruck. “You’re a character in a Kerouac novel?” I asked in amazement. I couldn’t have been more dazzled if he had told me he had committed the Lufthansa heist or slept with Doris Day.

Paul didn’t have much to say about those old days. I was left with the general impression that dealing with Kerouac in the flesh was somewhat less glamorous than it seems to an outsider like me—who only experiences it after the fact, in print.

The appearance of real-life beatniks in a Kerouac novel was a key part of its appeal. The lure of the road was only a superficial aspect—a kind of MacGuffin—in Kerouac’s literary vision. Far more important were the friends he gathered around him on his trips, valiant companions in a quest like the Knights of the Round Table. As Allen Ginsberg described it, Kerouac drew on a “tender consciousness, a realization of mortal companions whose presence together makes the event sacramental.”

The key figure in this puzzle is Neal Cassady, the patron saint of the American counterculture, although hardly worth considering as a literary figure based on his own writing ability. But Cassady’s significance has little to do with what he put down on paper—it’s what he did to people that counts.

For Kerouac, Cassidy was almost an alter ego, and showed up as a character in more than a half-dozen novels, most notably as Dean Moriarty in On the Road, a figure of almost like Gatsby-like significance in American letters. Ginsberg, for his part, fell in love with Cassady, and in the 1960s Cassady inspired a whole new group of bohemians, serving as driver on Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters bus. The New Journalism movement of that era also fed off of Cassady’s energy and personal charm, and he appears in the writings of Tom Wolfe and Hunter Thompson. For a while, Cassady lived with the Grateful Dead—Jerry Garcia called him a “12th-dimensional Lenny Bruce”—and I could devote a whole essay just to songs written about him.

What alluring qualities did Cassady possess that made him so irresistible? It’s hard to decipher them from his curriculum vitae, which includes:

Stints at three different reform schools;

Claims to have stolen approximately 500 cars between 1940 and 1944;

Three marriages, including one case of bigamy and a first marriage to 15-year-old LuAnne Henderson;

Multiple arrests, starting at age 14, and various periods of incarceration, including two years in San Quentin.

Cassady wasn’t even especially good looking. But photos convey a hyper-raw honesty and hungry sense of longing for the ecstatic—ingredients that drew others to him like moths to a flame. Even Cassady’s mug shots evoke this charismatic appeal.

Bigamy and grand theft auto are not the kind of credentials that advance your prospects on the literary scene nowadays, But in the overheated world of the beatniks, these various exploits made clear that Cassady knew how to be a rebel. Kerouac wasn’t capable of rebellion on this scale, but like Nick Carraway, he knew his Gatsby when he saw him.

For all his radical pretensions, Jack Kerouac never completely lost his innocent longings for something pure and beautiful—and that’s all the more surprising when we look at the seamier side of his cohorts and escapades. I suspect that’s why his work has held up the best of any of the Beat Movement novelists. Even today, at such a long distance, On the Road remains an endearing book, even an uplifting and transcendent one, despite the most ragtag plot and vagueness about the ultimate destination of this quintessential hitchhiker’s guide.

Not everyone was charmed at the time. When Kerouac and Cassidy stopped to visit William Burroughs in New Orleans on their next cross-country jaunt, the latter wrote to Ginsberg mocking the “sheer compulsive pointlessness” of these bebop pilgrims on a quest without definable goal. Kerouac’s biographer Ann Charter gets more to the heart of On the Road when she celebrates it s as the closest fiction has ever come to emulating ‘joyriding’—that sheer delight in movement for the sake of movement. “No book has ever caught the feel of speeding down the broad highway in a new car, the mindless joyousness of ‘joyriding’ like On the Road.”

The story of how the book was written adds to the mythic splendor. According to the usual account, Kerouac took a huge roll of teletype paper—stolen from a newspaper office where it was used to feed the United Press newswire printouts—and spooled it through his typewriter. Then he started writing feverishly, almost nonstop for 20 days, fueled by coffee and Benzedrine, capturing the bohemian spirit of life on the road in prose form. The end result was a novel of unprecedented spontaneity and jazziness on a 120-foot single-spaced scroll.

It was easy to mock this. Truman Capote, in his famous quip, said: “That isn’t writing—that’s typing.” But it was hard not to be impressed. In truth, Kerouac had prepared himself to write this seemingly improvised novel for a long time, previously working on various unfinished and discarded drafts before sitting down to write his scroll. And he continued to revise the manuscript in the ensuing years—despite promoting the legend of its spontaneous generation—and he had plenty of opportunities to do so, because six years would elapse before On the Road finally got published by Viking.

Even so, in those intense three weeks, Kerouac had finally found his true literary voice. I give him full credit: Nobody was writing like this in 1951. The preferred American style of prose was taut and blunt, and a whole generation had learned from Ernest Hemingway, Dashiell Hammett, and others who had developed this tough, chiseled idiom. Stream-of-consciousness wasn’t completely unknown in the US, and Faulkner had even given it some panache—but the idea of jazzy, free-form sentences describing counterculture life in spouts of youthful, dissident enthusiasm was Kerouac’s own. His best role model wasn’t a published writer, but the letters sent by his wild friend Neal Cassady.

Somehow he took these almost incoherent threads and turned them into a new way of writing fiction. And Cassady himself, transformed into character Dean Moriarty, became the driving force in the novel. This was a new kind of American hero, as much a loser as a winner—in fact, flaws and virtues are so jumbled in this figure that you reach the conclusion that some paradox was at the heart of the Beat Generation.

The very name of the movement made that clear. Beat both signified beaten down, but also raised up in the manner of a religious beatification. Up was down, and down was up. Kerouac flaunted the same contradiction in other names he gave to his counterculture movement—terms such as Dharma Bums or Subterraneans. In essence, this was a secularized religious concept, echoing the asceticism that Kerouac found so fascinating in Buddhist and Christian traditions, but somehow mixed with American hedonism. There had been nothing quite like it before in modern life, let alone modern fiction.

During those six discouraging years it took for On the Road to get published, Kerouac created most of his best work. He wrote Visions of Cody in 1951 and 1952; Dr. Sax was mostly written in 1952; Maggie Cassidy and The Subterraneans were completed in 1953—the latter allegedly over the course of three days, with the author again fueled by Benzedrine. Kerouac’s single most important contribution to literary theory, the brief essay “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose,” was written during the Fall of 1953. Mexico City Blues was conceived and written while visiting William Burroughs in 1955, this time put down on paper in a marijuana haze. Visions of Gerard and much of Desolation Angels were mostly written 1956.

These were Kerouac’s most significant achievements, yet he wrote them with virtually no encouragement or support except from a small number of people close to him. When he finally received $120 from Paris Review for rights to publish a section of On the Road, it was the most he had made from writing in years. But even when battling against a growing sense of failure and desperation, he continued to write, piling up manuscripts that today constitute the heart and soul of the Beat oeuvre.

How low did Kerouac sink during this period? Consider that when On the Road was finally accepted for publication by Viking, Kerouac was still living with his mother—except when he crashed with friends for short intervals—although he was now in his mid-30s. His schemes for earning a living had grown steadily more desperate, and he was now talking about hitchhiking to San Francisco and raising $25 by selling his blood to a blood bank. Then he would set up a hut down by the Mexican border, where Allen Ginsberg would join him. By tapping into Ginsberg’s unemployment benefits, they could last quite a while if they kept expenses under ten dollars per month. When the money was gone, they could always ship out as merchant seamen.

IV.

Kerouac was saved from this scrounging and scheming by the unexpected acceptance of On the Road after years of rejections. All the glory and fame he had long craved now came at him at warp speed. Glowing reviews in the New York Times and elsewhere turned him into an overnight sensation—but he didn’t know how to handle success. Kerouac had always been shy and an outsider, and wasn’t comfortable with admiring audiences. Often he needed alcohol to get through a public event, sometimes lots of it. The results were frequently disastrous, and stories of his outlandish drunken behavior circulated in literary spheres.

A high profile engagement with jazz musicians at the Village Vanguard ended after only a few days because of Kerouac’s drinking. On another occasion he got into a street fight on Minetta Lane in the Village, and was hurt so badly he needed to go the hospital—afterwards he feared he might have incurred brain damage.

His writing suffered from fame as much as did the writer. Shortly after the success of On the Road, Kerouac had a brief burst of productivity, writing one of his finest novels, The Dharma Bums, over the course of ten marathon sessions—sometimes producing more than ten thousand words at a single sitting. But after The Dharma Bums, Kerouac wouldn’t write another novel for four years.

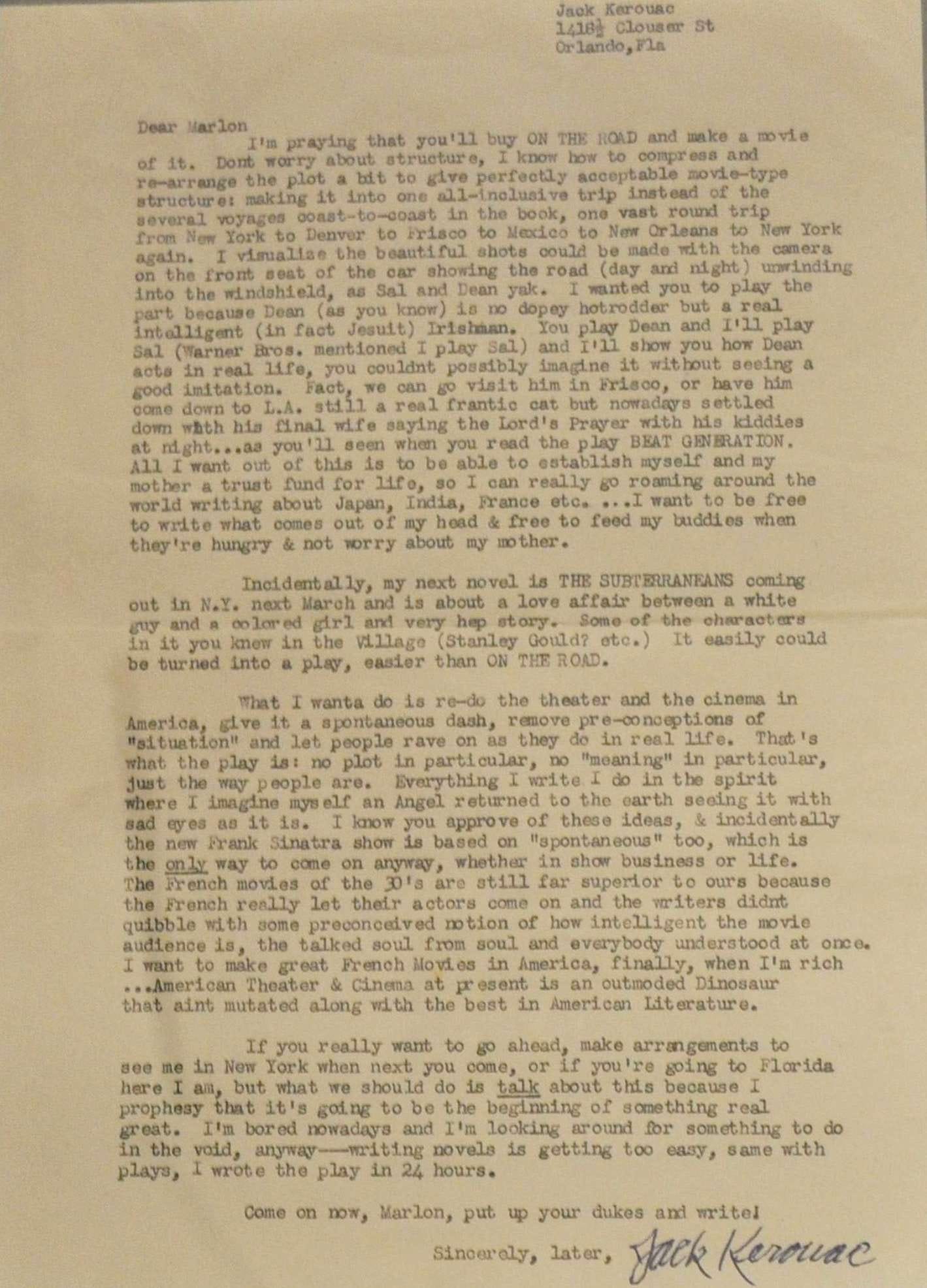

Kerouac paid his bills by doing occasional pieces at high prices, and there were no shortage of takers given his newfound fame. But even here, he often ransacked his old manuscripts for material, relying less and less on new inspiration. Some money also came from Hollywood, with The Subterraneans getting transformed into a 1960 film starring George Peppard and Leslie Caron, and also showcasing jazz musicians Gerry Mulligan and Carmen McRae. But Kerouac never enjoyed a big payday from the movie studios, although rumors circulated for a while that On the Road would get turned into a blockbuster film starring Marlon Brando. As it turned out, that classic novel wasn’t adapted for the big screen until 2012, long after the author’s death.

Fans forgave Kerouac for his excessive drinking and street fights—that was, after all, part of his public persona as a rebel. They were far more confused when he retreated into suburban private life, buying a conventional bourgeois home where he could live with his mother. She now set all the rules—his writing income went into their joint bank account. All checks had to be countersigned by mom, and she handed out spending money to Jack for beers and cigarettes. Unsavory friends such as Allen Ginsberg weren’t allowed to visit. No drugs were permitted in the family home. Etc. As it turned out, Kerouac’s mother, Gabrielle-Ange Lévesque (1895–1973), would outlive her son by four years. So his entire life was spent as a momma’s boy—such a sharp contrast from the way readers envisioned Jack Kerouac.

He had one last great work of fiction in him. An invitation to stay at Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s cabin on the central coast of California resulted in Kerouac’s 1962 novel Big Sur. The trip itself was a disaster, with Kerouac drinking more heavily now that he was out from under his mother’s thumb. At one especially paranoid moment, he even decided to leave the cabin behind, planning to hitchhike north. In an ironic twist, Kerouac couldn’t get a ride from 9 AM to 4 PM—every passing car ignoring the famous author of On the Road while he trekked up Highway One.

That would be the last time Jack Kerouac ever tried to thumb a ride. When he finally decided to return to the East Coast at the end of his disastrous California retreat, he turned in his train ticket and bought a seat on an airplane instead. But even if his body and psyche were in collapse, he somehow managed to write one last great book based on this visit—feverishly set down on a teletype roll over the course of ten days. But after Big Sur, published on September 11, 1962, Kerouac had no more to say. He made one last attempt to resuscitate his epic travels with a visit to France, but it only produced a second-rate 1966 novella, Satori in Paris.

In a 1964 interview, Kerouac admitted that his best work was behind him—completed in the 1950s “when nobody knew me, nobody cared.” Even his fans grew wary. Once while living in Florida with his mother, some youngsters came pounding on his door. When the famous author opened it, he saw a group of aspiring beatniks with “Dharma Bums” written on their jackets. But the visitors were taken aback by the awkward, middle-aged man they encountered, who bore no resemblance to the road warrior they had hoped to meet. Their disappointment was palpable. Kerouac, for his part, was at a loss for words, feeling himself acutely incapable of living up to the legend he had created over the course of so many books. He later admitted to David Markson that this was one of the saddest moments he had ever experienced.

This inability to connect with the younger generation of the 1960s is perhaps the most tragic part of the Kerouac story. He did more than anyone to pave the way for the hippie movement—and I don’t make that claim lightly. The whole culture shift of the 1960s was like a brand extension of beatness, with formerly counterculture ways now going mainstream in every city across the nation. Kerouac should have celebrated this, even presided as a kind of guru or wise tribal elder, but he merely felt left behind and out-of-touch.

He had never viewed his writing as a political statement, and now watched on in disbelief as so many agendas and ideologies claimed him as their own. He saw himself as an American in the spirit of Melville, Whitman, and Emerson, even as a kind of patriot. When Allen Ginsberg wrapped an American flag around Kerouac at a New York event, Jack took it off and lovingly folded the Stars and Stripes, putting it aside for safekeeping. He even told his biographer Ann Charters, over the course their work together on a bibliography in 1966, that he would be willing to go to Vietnam and fight as a marine.

Kerouac was no stranger to mind-altering substances, but the new drugs merely left him puzzled and distressed. While hippies glamorized pot and acid, Kerouac kept mostly to wine and beer. His one LSD trip, under the guidance of Timothy Leary, had been a disaster, and he blamed Ken Kesey and other 1960s rebels for the death of his friend Neal Cassady, who had gotten caught up in their psychedelic idealism, and collapsed alongside a Mexican railroad track while high on a rainy night in February 1968. Cassady was just 41 years old at the time of his death. When Kerouac heard the news, he got so drunk that police took him off to jail.

Kerouac would only survive Cassady by twenty months. The official cause of death was internal bleeding, but years of alcohol abuse had taken their toll. Even Kerouac must have seen it coming. He had put his will in order, and transferred ownership of his home to his mother—who had now lived long enough to see all three of her children dead and buried. Kerouac’s old cronies from the Beat Movement came to the funeral to pay tribute, but he had fallen out of touch or cut ties with many of them long before. He was just 47 when he died, but it was hard not to conclude that Jack Kerouac had already come to end of his road long before his body finally gave out.

V.

It’s tempting enough to dismiss Kerouac and his entire Beat Movement as a promise undelivered. They claimed to offer liberation from a monolithic, hidebound society, but seldom delivered more than tilting at windmills. Kerouac’s prose is sometimes inspired, even ecstatic, but not with the consistency of Faulkner, Proust, or Woolf. I cheer him on as I read page after page, much as I would a sax soloist at a jam session, and am frequently rewarded with a chorus of righteous sentences and hypnotic jive; but the reader never loses the feeling that Kerouac is operating at the limits of his ability to plan and control the words.

Like a motorist going too fast on those cross-country jaunts he loved to describe, the risk of a spinout or crash is ever present. And if you read enough of his work, you learn that dead-ends and breakdowns are an inescapable part of the experience. But I’m still not sure this is a flaw in the books. Could Kerouac really have achieved that tone of wild exhilaration with a more conspicuously planned approach? You might as well ask Coltrane or Rollins to write out their sax solos in advance. With Kerouac as with the jazz masters, much of the appeal comes from their willingness to throw all caution to the wind.

There was a price to pay for all this. So much of Kerouac’s life, like his plots, never achieved anything resembling closure. I’m reminded of his failed attempt to go mountain climbing with fellow-beatnik Gary Snyder—perhaps the most impressive individual in the whole Beat Movement based on the inspiring depth and breadth of his zen-infused life. Kerouac first complained bitterly when he learned he couldn’t bring a jug of wine in their rucksacks, struggled during the ascent, and chickened out in fear before reaching the summit. This earned him a new nickname: “The Buddha Also Known as the Great Quitter.”

To some degree, that sobriquet covers Kerouac’s whole life. Yet I cut him some slack, and grasp that, in a strange sort of way, these very contradictions made him an even more powerful novelist, perhaps a genuinely spiritual one. An honest novel of religious awe has to encompass the true nature of transcendence, realistically conveying that moments of ecstatic insight are few and hard to come by in our constrained human state—yet, for all the obstacles, this is as high of a quest as we can envision. You don’t take those kind of trips with the smugness of a master, rather with the humility of a disciple. That’s the story of On the Road, and it’s the story of all Kerouac’s great works. He may be a dreamer and a schemer, but the raw authenticity of his seeking resonates on every page.

“Escape no longer involves a risky journey on the road, but a corporately-controlled sinking into a phony, pre-fab Metaverse, where even hitchhiking requires an avatar and subscription account.”

More than any of his cohorts, Kerouac craved the beatification in the Beat Movement, and if he only got the smallest taste of it, that’s just another reason to extend our sympathy and compassion. He tried, fervently and desperately—and wanted to bring us along for the ride.

And I’m even more willing to embrace Kerouac in this stultifying cultural moment we live in a century after his birth. There is little resembling a counterculture in American life nowadays. Everything seems joined together in a monolithic and monochrome culture, and nothing is less cool or hip or fashionable than going against the grain. Even the youth movement, where we would naturally seek a counterculture, is caught up in fear and avoidance of anything that might genuinely break out of the mold. Escape no longer involves a risky journey on the road, but a corporately-controlled sinking into a phony, pre-fab Metaverse, where even hitchhiking requires an avatar and subscription account.

It’s hard not to miss Jack Kerouac in such a dead-end time, which sometimes resembles a culture suffering from arteriosclerosis, a hardening of the attitudes. I’m not sure even he could deliver much in the such an environment. But then I recall that Kerouac’s own time was perhaps even more rigid—filled with rules, blacklists, rampant censorship, fear, and pervasive conformity. Yet Kerouac not only managed to stand out as a free spirit in a constrained age, but even put some of his rule-breaking mojo down on paper.

Kerouac, that Buddha Also Known as the Great Quitter, had a different nickname for himself—on one of his crazy road trips he adopted the identity of a “Don Quixote of Tenderness.” I like that term, because no one was more mistaken than Don Quixote, who misread every situation and person in his own topsy-turvy way, but still earns our admiration—because sometimes the dreaming is more worthy of our respect than the deadening ways of the rest of society. That’s exactly how I view Jack Kerouac and his oeuvre.

Is there a single promising young American writer today who would make the following declaration as his credo and talisman—these words coming from the character Japhy Ryder (based on Gary Snyder, who is still with us and turns 92 in a few days) in The Dharma Bums:

“I see a vision of a great rucksack revolution thousands or even millions of young Americans wandering around with rucksacks, going up to mountains to pray, making children laugh and old men glad, making young girls happy and old girls happier, all of 'em Zen Lunatics who go about writing poems that happen to appear in their heads for no reason and also by being kind and also by strange unexpected acts keep giving visions of eternal freedom to everybody and to all living creatures.”

Or consider this beloved passage from On the Road:

“The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’”

I’m not sure how much wisdom I can extract from these words today, but I’m not ready to abandon such hopes, however naive. So count me among the rucksack rebellers, willing to say ‘Awww’ along with whatever crazy dreamers and mad ones still out there, wishing there were more of us to make a dent in the prevailing mindset. May all of us enjoy “strange unexpected acts” of kindness, and grant “eternal freedom to everybody and to all living creatures.” May we all learn how to become “Don Quixotes of Tenderness.”

So, Jack, I’m confidently celebrating your centenary, and giving you the go-ahead to keep on the road for a few more decades, maybe even another hundred years. And I’d be especially happy to see others picking up their own rucksacks, and joining us on the trip.

This was fantastic! I share your grief at seeing how "safe" people often play it these days, bowing to conformity and orthodoxy. It's anodyne and soul-crushing.

Thank you Ted. I think it is now time for me to dig out the old copy and read it again afresh.