Jack Kerouac at 100: Part 1 (of 2)

On his 100th birthday, I consider whether the King of the Beats still speaks to us today—or is just a dated relic of a hipster past

The 100th birthday of Jack Kerouac will be celebrated all over the world today. Or will it? How many people still take Kerouac and the Beat Movement seriously in the current moment?

Even the word hipster has turned into a joke and insult nowadays—and that’s a term that will always be linked to Kerouac and his cohorts. So it’s worth asking how many people still march to the Beats as their different drummers, and whether the books they left behind can still serve as guides in a society that has lost its faith in the counterculture. You could even make a case that there is no genuine counterculture anymore.

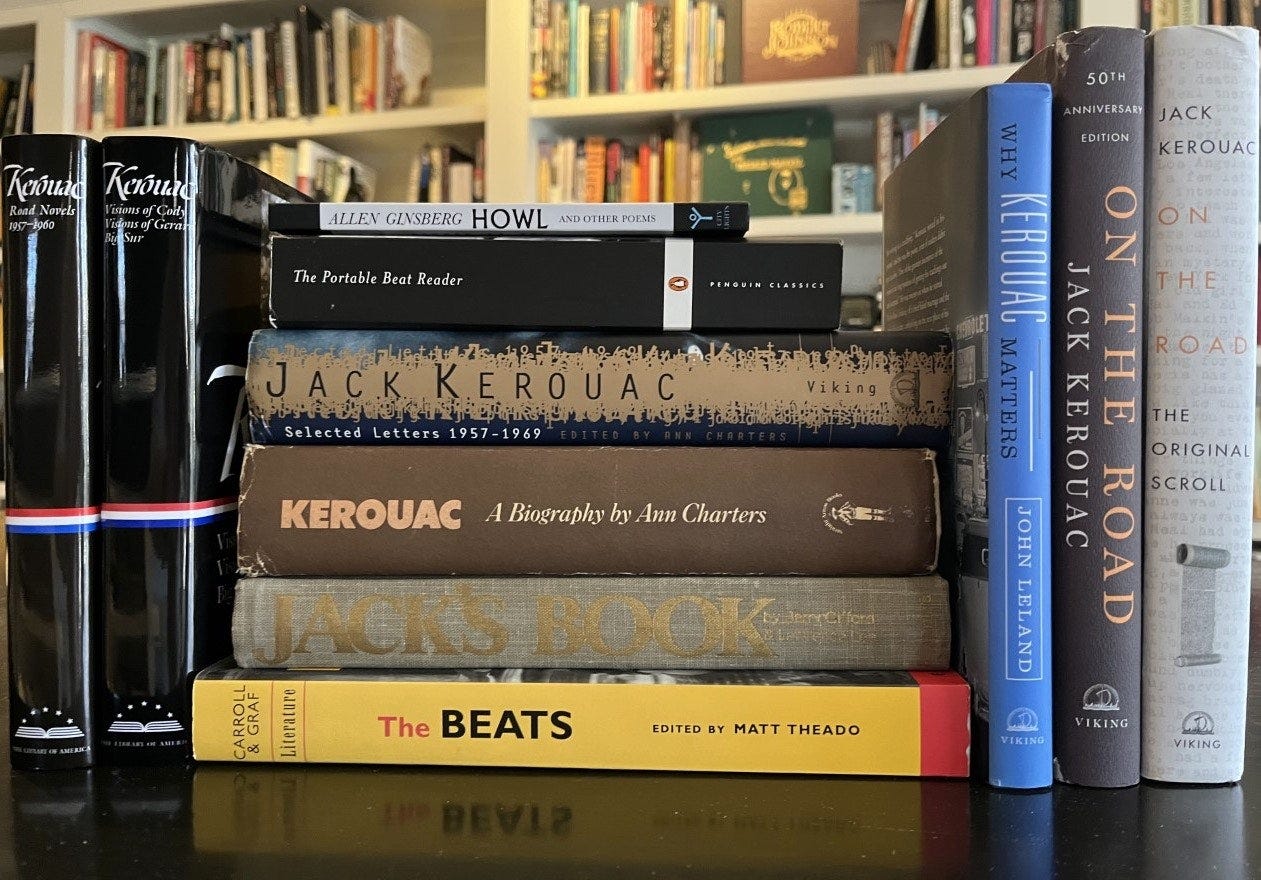

But let’s be fair. If you open up Allen Ginsberg’s Howl right now, you will discover that it describes San Francisco today just as well as it did back in 1956—maybe even better. Merely mix in a few names of tech companies and trendy consumer brands and it could pass for contemporary reportage. And Kerouac’s On the Road not only still sells copies but now gets treated as a serious work of fiction, despite decades of mockery. In fact, it’s easier nowadays to see the author’s links to Melville, Whitman, and all those other crazy American dreamers.

So with both hope and trepidation, I returned to Jack Kerouac recently, trying to gauge how much he still means in the current moment.

Note that my assessment below is too long to fit in a single email installment of The Honest Broker, so I’m breaking it up into two parts.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

JACK KEROUAC AT 100: Part 1 (of 2)

by Ted Gioia

I.

Literary reputations don’t last long nowadays. When I published a series of essays on one of my favorite novelists, John Fowles, to commemorate the tenth anniversary of his death, I seemed to be the only person who even noticed the milestone—and Fowles had been a literary lion just a few years before, with bestsellers and movie deals to his credit.

And it’s even worse for John Updike, Norman Mailer, and Saul Bellow—maybe the three most celebrated American novelists of their day, yet now missing in action from course syllabi, magazine essays, and (most telling of all) bookshop shelves. Much the same might be in store for J.D. Salinger and even Ernest Hemingway, who both hang on as important names, but are more often mocked than praised in the overheated world of social media lit crit. Harper Lee might even get cancelled, a mystifying development for a writer considered so forward-looking just a short while ago. Philip Roth still has devoted fans and a seemingly impregnable reputation, but in a strange twist, his high-profile biography got pulled from the market just 15 days after release.

I could go on and on. And if it seems like I just took a cheap shot at one of your literary heroes, please remember I’m merely the messenger.

I suspect that several of those reputations will eventually come back to life—but it may not happen for another generation. In fact, I have a hunch that a whole bunch of scholars, circa 2050 AD, will get tenure by rediscovering novelists from the Erased Generation. But for the time being, I can only say (in the words of 2 Samuel 1:19): How the mighty have fallen!

Then we come to Jack Kerouac, who still seems to be going strong at the hundred year mark. In the last decade, filmmakers have turned On the Road and Big Sur into movies, and Kerouac has also shown up as a character in Beat (2000), Howl (2010), and Kill Your Darlings (2013), as well as a major figure in the 2011 documentary Love Always, Carolyn. There’s even a Beat Museum now, across the street from City Lights bookstore—another survivor, seemingly immune to the cultural destruction around it—where you can buy Kerouac T-shirts and coffee mugs.

Judging by these varied projects, Kerouac still seems young at this three-digit age. Yet it’s not entirely clear whether it's his books that validate him as a legend, or his legend that validates his books. I suspect that Kerouac is embraced more as a symbol of free-spirited independence (an ironic fate given the realities of his life, as I describe below) rather than as an author to read and emulate.

Like so many of his readers, I came to love Kerouac when I was still in my teens, and I find my feelings are still a jumble when I try to revisit and reassess his literary reputation so many decades later. Are those beatnik novels genuine masterpieces or just empty posturing—or maybe a little of both?

In a way this confusion is fitting, because everything about Kerouac’s life was a jumble of contradictions. He is lionized as the symbol of independence and rebellion, but actually spent most of his life residing with his mother. Celebrated as the ultimate hitchhiker, the patron saint of wanderers on the road, Kerouac rarely thumbed a ride—even his famous trip cross country, celebrated in On the Road, required a number of bus tickets, and he never tried anything comparable again. He became a hero of activists and protesters, but his own political allegiances were as conventional and conformist as they come.

Or consider how Kerouac got enshrined as a guide to the jazz culture of his time, but his grasp of the music was never more than haphazard, albeit wide-eyed and enthusiastic. He couldn’t write about Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, or Billie Holiday without misspelling their names. He thought vibraphonist Lionel Hampton played saxophone, and referred to legendary bebop drummer Max Roach as Max West. You can admire his passion for the music and, to Kerouac’s credit, he even captures much of its spirit in his prose, but you can’t really take him as a reliable guide to it.

The paradoxes began literally at his birth. Although Jack Kerouac is considered a quintessential American author, he was actually baptized as Jean Louis Kirouac, a name that harkens back to his family’s French Canadian origins, and links him more distantly to Cornish Celtic ancestors who carried the name Kerouac’h. Kerouac didn’t even learn English until first grade—and thus belongs in the rare group of great writers in that language (Nabokov, Conrad, Brodsky, etc.) who originally spoke another tongue.

I’d love to imagine Kerouac as the descendant of a mystical Celtic bard, and who knows that could very well be the case. But the more significant truth is that Jack Kerouac has always been a magnet for reader’s imaginative fancies. I’m no exception to the rule: When I first read his books, I projected my own aspirations and ideals into them. I probably still do that.

When I consider Kerouac nowadays, so long after I first encountered his work, I’m struck more by his innocence than his independence. I love him more as a dreamer than a rebel. I prefer his rapt idealism over the details of his endless road itineraries. I especially resonate with the sentiments of kindness and compassion that permeate his books. I suspect that those qualities, for all his flaws and failing (and there were many), will play a key role in preserving and perpetuating Kerouac’s literary legacy.

And I note, in passing, that the posthumous American literary reputations that seem the most rock solid right now often involve individuals who come across as genuinely caring people in their books—I’m thinking here of Kurt Vonnegut, Ray Bradbury, Octavia Butler, and David Foster Wallace, for example—while those who took center stage as self-referential, preening, and Maileresque (can I coin that word?) haven’t retained their charm quite so well.

I place Kerouac with that former group. He was no saint, but his instincts were kindhearted. He wanted to be a Dharma bum, even if he didn’t fit the role very well. Even in his books, where he inevitably shows up as a character, he often preferred to give himself the role of a sidekick, assigning more glamour to another protagonist and a transcendent worldview he hadn’t quite mastered himself. He never claimed to possess the highest wisdom, but was instead a constant seeker after it—and that sense of the search is at the heart of his oeuvre. You rarely hear the word humility applied to any great American novelist, but Kerouac genuinely earned it.

Who else, except Jack Kerouac, would envision God as Pooh Bear, as happens in those glorious final sentences of On the Road? Here’s Mark Murphy delivering that famous passage in his intro to a track on his album Bop for Kerouac. Such childlike hope still gives me chills, and I hesitate to analyze the dream too deeply.

If you study Kerouac’s biography, you discover that he earned that humility in the most painful way possible. He tried and failed at almost everything in his life, from his football career to his marriages and affairs, and no one knew it more than Kerouac himself. But the writing sustained him through all of the disappointments, although it was a failure, too, for more years than it was a success.

In fact, you could make a case that Kerouac only genuinely lost his way after he was granted adulation and acclaim in large doses during those final desolate years of his life. The reality of pop culture celebrity could never match the overheated dreams that preceded it. But if he was just one more failed dreamer, his readers love him all the more for that fact.

At least, I do.

II.

Long before Kerouac wrote On the Road, Kerouac had already fantasized about a liberating journey. His mother decorated his boyhood bedroom with the nursery rhyme motto: “Jack be nimble, Jack be quick,” and he apparently took the admonition to heart at every phase of his life, whether eluding tacklers during his brief but promising football career—which might have blossomed into genuine stardom at Columbia University until a broken leg and his own restlessness derailed his sports ambitions —or later moving to his own personal beat on the roads of America.

Kerouac fittingly ran away from home at age eight, accompanied by some childhood friends, only to learn that a night outside cold and wet wasn’t as romantic as it had seemed. That failed boyhood escape could serve as the symbol of his later life. Yet the urge to move, even without destination, never entirely left him.

But Kerouac always set himself up for disappointment when he went on the road. He simply wanted too much from his trips, his epiphanies, his glimpses of enlightenment. He was a utopian, and it rarely ends well for people of that temperament.

If you doubt me, just look at the names. In his most famous novel, Kerouac appears as the character Sal Paradise—and paradise is the one thing we are denied in this fallen earthly realm. Even the words beats and beatniks, which became inextricably linked to Kerouac and his entire cohort, possess a utopian resonance. The beat was the rhythm of jazz, it was beaten-down outsider on the fringes of society, but above all, for Kerouac, it signified the beatified visionary on a pilgrimage to a better life.

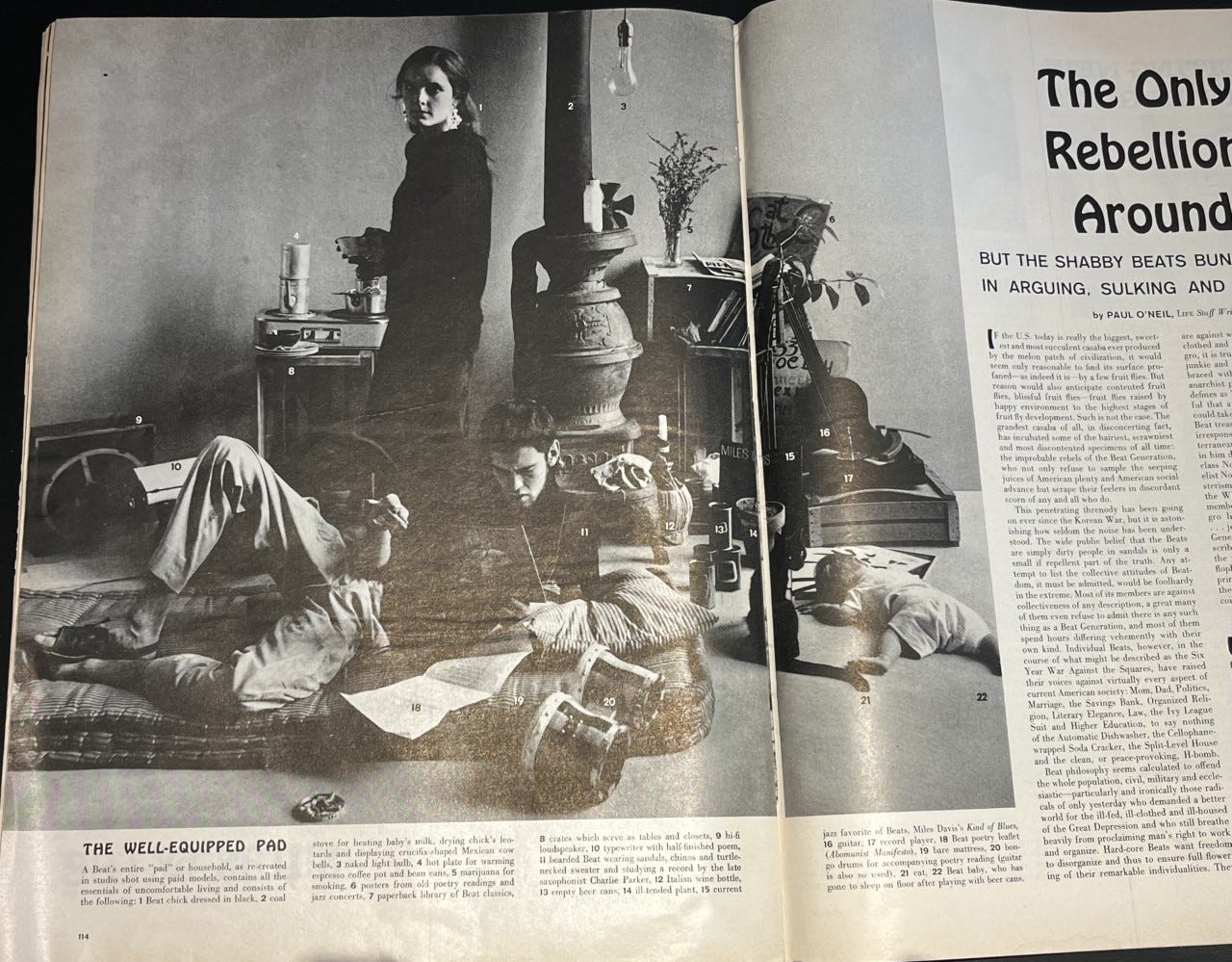

The Beat Movement he set in motion wasn’t very large, at least at start. Everyone was talking about the Beats at the close of the 1950s, but Life magazine confidently assured its readers that there were “probably less than a thousand Beats now in San Francisco.” In Los Angeles, they estimated the numbers as “no fewer than two thousand.” How they came up with these numbers is a grand mystery—was there a counterculture census underway?—but Life further explained that “perhaps ten percent” of the movement consisted of African-Americans.

The media turned the Beats into a joke. Yet somehow the Beat Movement morphed into the hippie scene a few years later, and by then the number of counterculture free spirits had grown into the millions. And though you may not want to give Kerouac full credit for setting this revolution in motion, he really belongs at the top of the list of mid-century thinkers who anticipated how American life would evolve—or, even more to the point, offered a guide on the printed page.

Kerouac’s life itself served as a kind of mythology. And that was true even before he published a book. Readers of The Spectator, the student newspaper of Columbia University, were already caught up in that mythology back in the 1940s, when Kerouac first appeared in its pages as a promising football star, but he soon started taking on all kinds of other archetypal qualities. By the time Kerouac was arrested in 1944 as an accessory to murder, after his friend Lucien Carr killed David Kammerer in Riverside Park, he had turned into a troubling tabloid newspaper character. And then The Spectator breathlessly reported both Kerouac’s refusal to pay his $5,000 bail, and his decision to get married —while still in jail!—with guards escorting him to the Municipal Building for the brief ceremony, then bringing him back to his cell.

Kerouac hadn’t even published a book at this point—that was still years in the future—but people already knew his name and shared gossipy details of his behavior.

The real story is not quite so strange as the legend, as was often the case with Kerouac. He married his girlfriend Edie Parker because she needed that commitment before her parents would provide bail money for Kerouac. But already, at age 21, the future writer was living a life that seemed straight out of a movie script. A short while later he moved to Michigan with Edie, where he got a job counting ball bearings at a factory. It’s like a scene out of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, no? But soon Kerouac had left Michigan (and marriage) behind, shipping out as a merchant marine—but first reconnecting with a strange young man named Allen Ginsberg, another friend of Carr’s, at the West End near Columbia the day before he left.

But this trip—like so many Kerouac took with such vague, yearning aspirations—was a disaster. He jumped ship at the first opportunity, put away his sailor’s garb, and headed back to New York. Kerouac was now a dropout from football, from college, from marriage, and the merchant marines.

Returned to Manhattan, the future author of On the Road moved into Allen Ginsberg’s dorm room—Ginsberg would soon get suspended from Columbia for this and other infractions. Kerouac just as quickly moved on to the apartment of William Burroughs. These friends began to hatch plans on how to become famous writers. In effect, this was the birth of the Beat Movement, a literary and cultural alignment that would shake up American life over the course of the next two decades. . . .

That’s part one. Click here for JACK KEROUAC AT 100 (Part 2).

I read Kerouac before I took my first trip across country in 1960, from NYC. He made a great impression on me on freedom with sex, beatific, personal experiences he related. Kerouac enlightened me to contemporary thinking. I had three years of Cooper art college; five years living in the Yukon Wilderness, on the river, learning about hunting and gold panning. I read Hemingway, Mark Twain, plus the writer from the south east and one from California, who brought a dog to the gold fields. Names I forgot but which you will know instantly. Remember the author in Ca. whose family came from Serbia? He wrote a book comprised of letters from him to his family. Thanks for bringing me back to those days, where I ought to start my memoir. I wasn't patient for keeping a journal. Now I know how important a journal is to a writer, an artist, an adventurer.

Nice article. I never read On the Road when I was a kid. It wasn’t until five years ago I read it. He took the kind of trip many of us wish they could have — but didn’t — sometime in our life. On a separate point, maybe some authors aren’t chic today. Hemingway comes to mind with his outsized life but if you read his short stories and work before For Whom the Bell Tolls, it’s beautifully written full of great ideas. If you neglect him, you’re only cheating yourself. Going back to On the Road. My favorite character: Dean aka Neil Cassidy. Outsized in so many ways.