Is Mid-20th Century American Culture Getting Erased?

They call it the "Greatest Generation"—so why is its art disappearing?

A few days ago, The Atlantic published an article on esteemed author John Cheever (1912-1982). But the magazine is almost apologetic, and feels compelled to admit the “final indignity” suffered by this troubled author—”less than 30 years after his death, even his best books were no longer selling.”

What a comedown for a writer who, during his lifetime, was a superstar contributor to The New Yorker, and got all the awards. Those included the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the National Book Award, and the National Medal for Literature.

But that’s not enough to keep any of his books in the top 25,000 sellers at Amazon. Try suggesting any of Cheever’s prize-winning works to your local reading group, and count the blank stares around the room.

And it’s not just Cheever. Not long ago, any short list of great American novelists would include obvious names such as John Updike, Saul Bellow, and Ralph Ellison. But nowadays I don’t hear anybody say they are reading their books.

And they are brilliant books. But reading Updike today would be an act of rebellion. Or perhaps indulging in nostalgia for a lost era.

The list goes on—Joseph Heller, Bernard Malamud, Carson McCullers, Robert Penn Warren, Katherine Anne Porter, James Agee, etc. Do they exist for readers under the age of forty?

Their era—mid-20th-century America—really is disappearing, at least in terms of culture and criticism. Anything from the 1950s is like an alien from another planet. It simply doesn’t communicate to us, or maybe isn’t given a chance.

And what about music?

The New York Times recently noticed that mid-century American operas never get performed by the Met. It’s almost as if the 1940s and 1950s don’t exist at Lincoln Center.

During those years, the United States was at the peak of its global power and influence. Its cultural institutions were well funded and widely admired. America was blessed with an extraordinary generation of talented artists, both émigré and homegrown.

But the operatic masterpieces of the period are now mostly forgotten.

If you want to support my work, take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

The author Joshua Barone calls attention to Vanessa (1958) by Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti, which won a Pulitzer Prize and was hailed as a modern masterpiece at its debut. There were 17 curtain calls on opening night, and the Times announced that this was “the best American opera ever presented.”

Barone asks:

Why, then, is it impossible to see Vanessa at an opera house like the Met? That’s a question with deeper implications: If one of the finest, most enduring American works of the mid-20th century can’t make it to the grandest stage in the country, what hope is there for others from its time?

But Vanessa is hardly an isolated case. Other operas from that era found a crossover audience on Broadway—and seemed poised to become the next Porgy and Bess.

Street Scene (1946), by Kurt Weill and Langston Hughes, crossed over to Broadway, and helped pave the way for the later success of West Side Story. Weill won the first Tony for his score, and some of its songs had crossover success with Benny Goodman an other jazz bands.

Regina (1948) by Marc Blitzstein boldly anticipated the later genre-crossing of postmodernism, incorporating ragtime, spirituals, Chicago jazz, Victorian parlor music, the modernist orchestral vocabulary, even rapped vocalizing. It also played both in opera houses and on Broadway, and was lavishly praised in its day.

The Consul (1950) by Gian Carlo Menotti had a long successful run on Broadway and won a Pulitzer Prize and the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award as “Best Musical.”

But don’t expect to see any of these works performed at the Met.

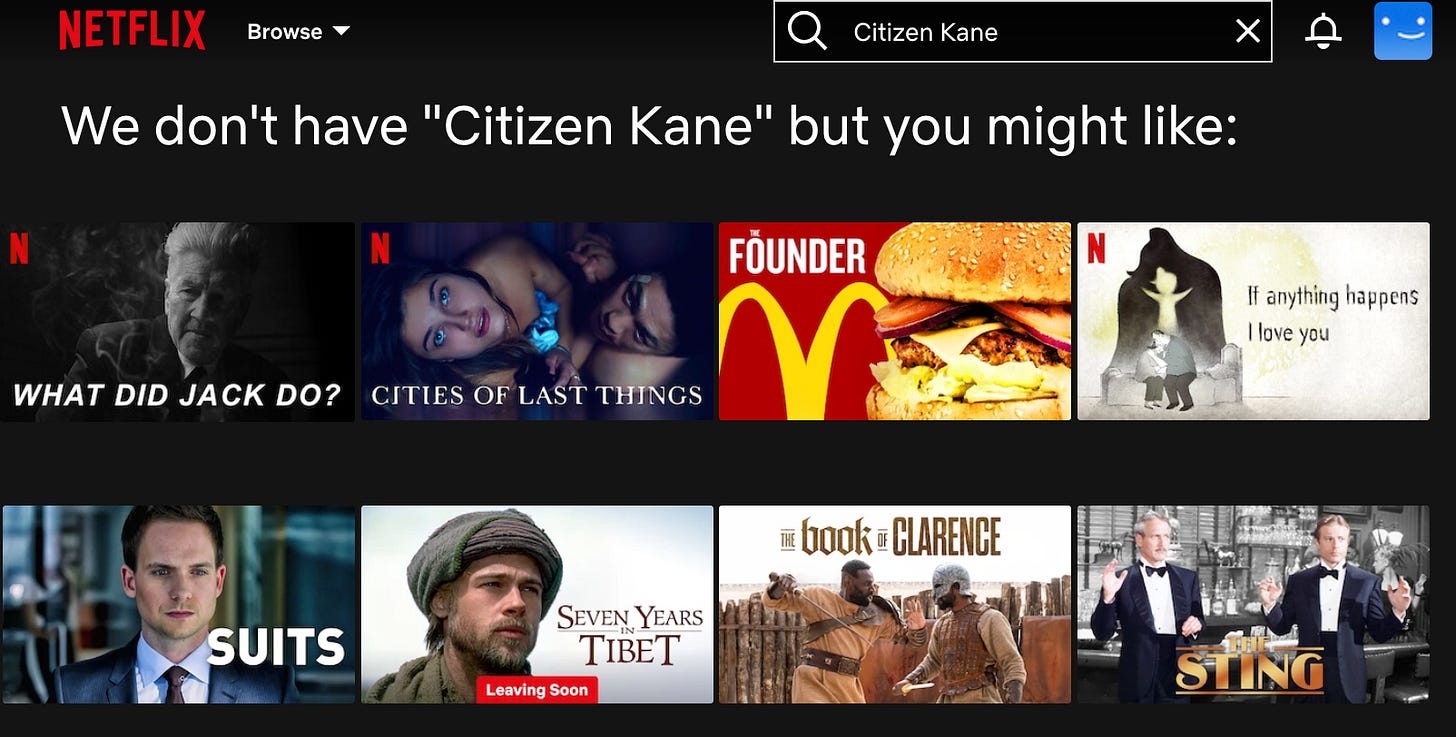

When I try to find Citizen Kane on Netflix, the algorithm tells me to watch a movie about McDonald’s hamburgers instead.

That institution will support music by living American composers, and old operas (almost always European) from before World War II—but avoids the period in-between.

Is it possible that America could reach the peak of its global power after World War II, but fail to produce high culture works of lasting merit? That seems unlikely, no?

But I see the exact same thing in jazz. Most jazz fans want to listen to music recorded after the the emergence of high fidelity sound in the late 1950s. So they are very familiar with Kind of Blue (1959) and what happened after, but know next to nothing about jazz of earlier periods.

If I were making a list of the greatest American contributions to music, my top ten would include Duke Ellington’s music from the early 1940s and Charlie Parker’s recordings from the mid-1940s. But even jazz radio stations refuse to play those works nowadays. So what hope is there that these musical milestones will retain a place in the public’s cultural memory?

Jazz musicians who died in the mid-1950s, such as Art Tatum, Charlie Parker, and Clifford Brown should rank among the great musicians of the century, but somehow fall through the cracks. Maybe if they had lived a few more years, they would get their deserved acclaim. But the same fans who love Monk, Miles, Ornette, and Trane often have zero knowledge of these earlier figures.

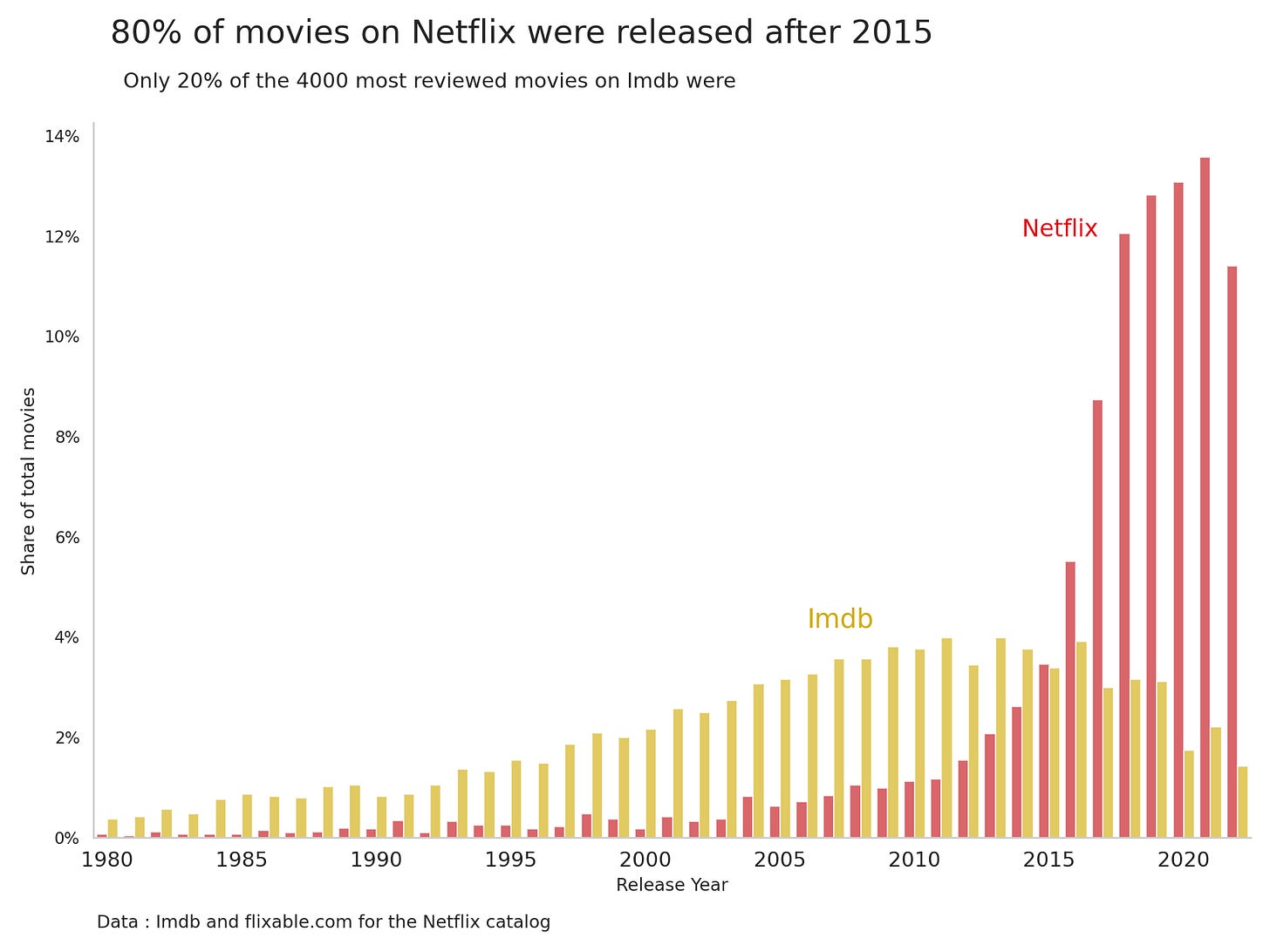

Now let’s consider cinema from the 1940s and 1950s. It doesn’t exist on Netflix.

You might say that Netflix has eliminated the entire history of cinema from its platform. But it especially hates Hollywood black-and-white films from those postwar glory years

Citizen Kane is the greatest American film of all time, according to the American Film Institute. But when I try to find it on Netflix, the algorithm tells me to watch a movie about McDonald’s hamburgers instead.

The second best American film of all time is Casablanca, according to the AFI. When I tried to find it on Netflix, the algorithm offered me an animated film from 2020 as a substitute.

The sad reality is that the entire work of great filmmakers and movie stars has disappeared from the dominant platform. It wouldn’t cost Netflix much to offer a representative sample of historic films from the past, but they can’t be bothered.

Is there any creative field where America’s best work from the 1940s and early 1950s is cherished and celebrated?

The symphonies from that era have almost entirely disappeared from the repertoire.

The popular songs are no longer familiar to us (except for a few holiday tunes resurrected each Christmas).

The musicals (by Cole Porter, Rodgers & Hammerstein, Irving Berlin, etc.) are clearly superior to today’s Broadway fare, but are fading from the public’s memory.

Not all of these works deserve lasting acclaim. Some of the tropes and attitudes are outdated. Avant-garde obsessions of the era often feel arbitrary or constraining when viewed from a later perspective. Censorship prevented artists from pursuing a more stringent realism in their works.

But those reasons don’t really justify the wholesale erasure of an extraordinary era of American creativity.

What’s happening? Why aren’t these works surviving?

The larger truth is that the Internet creates the illusion that all culture is taking place right now. Actual history disappears in the eternal present of the web.

Everything on YouTube is happening right now!

Everything on Netflix is happening right now!

Everything on Spotify is happening right now!

Of course, this is an illusion. Just compare these platforms with libraries and archives and other repositories of history. The contrast is extreme.

Please support my work by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

When you walk into a library, you understand immediately that it took centuries to create all these books. The same is true of the Louvre and other great art museums. A visit to an Ivy League campus conveys the same intense feeling, if only via the architecture.

You feel the weight of the past. We are building on a foundation created by previous generations—and with a responsibility to future ones.

The web has cultivated an impatience with that weight of the past. You might even say that it conveys a hatred of the past.

And the past is hated all the more because history is outside of our control. When we scream at history, it’s not listening. We can’t get it cancelled. We can’t get it de-platformed. The best we can do is attach warning labels or (the preferred response today) pretend it doesn’t exist at all.

That’s how Netflix erases Citizen Kane and Casablanca. It can’t deny the greatness of these films. It can’t remove their artistry, even by the smallest iota.

But it can act as if they never happened.

This is especially damaging to works from the 1940s an 1950s. These are still remembered—but only by a few people, who will soon die.

This is the moment when works from 80 years ago should pass from contemporary memory and get enshrined in history. But that won’t happen in an age that hates history and wants to live in the eternal present.

Like Peter Pan, the web (and increasingly its users) doesn’t want to grow up.

But that eternal present is a lie, an illusion, a fabrication of the digital interfaces. And this not only destroys our sense of the past but also undermines our ability to think about the future.

In an environment without past or future, all we have is stasis.

So it’s no coincidence that culture has stagnated in this eternal digital now. The same brand franchises get reheated over and over. The same song styles get repeated ad nauseam. The same clichés get served up, again and again.

You need to understand that the web turns everything into a meme. And a meme is always repeated. So when all of culture gets addressed this way, stagnation is inevitable.

If you think the past is a heavy burden, just wait and see how heavy the present feels after it grows to such monstrous proportions.

But there’s a whole universe that exists outside of your phone. All you need to do is turn away from the screen—even for just a short while—to understand that the culture of now is embedded in something much, much larger.

When we do that, we start seeing that our legacy from the past is an inherited treasure—and both offers us riches and imposes responsibilities.

The day will come when we, too, hand off our cultural heritage to future generations. It would be best if we had something more than memes and brand reboots to give them. Taking some measure of history—past, present, and future—is where that starts.

Most people who know about pre-war jazz know of me as the former bassist with the Jim Cullum Jazz Band, the host band for the (now retired) public radio series "Riverwalk Jazz." These days I live in Soutwest Florida and work mostly with bands and singers of the Great American Songbook. A few years back, during a vacation to New York, I was invited by Jon-Erik Kellso to play one of the Sunday afternoons at the Ear Inn on the Lower West Side. I had lots of fun with Jon's "Ear Regualrs." The clarinet player, Dennis Lichtman, invited me to hear his Tuesday band at Mona's on the Lower East Side. My girlfriend and I found ourselves among the few people in the place with grey hair. The dominant style of jazz I heard was pre-war Swing. At midnight the jam session began, and there was a long line of young players waitng their turn to sit in. I heard very little post-war style jazz, and most of it was just swingin' like crazy. I was very happy to know that such a righteous bastion of pre-war jazz existed and was thriving. I hope it's still going strong.

And now I'm encountering quite a few youngsters interested in the old, Jurassic stuff. A cadre of 20- and 30-somethings in Austin led by cornetist David Jellema. The Parker Jazz Club donwtown run by a guy who remembered me from his High School days in San Antonio and visits to The Landing where we played 6 nights a week (I was there for 19 years).

Currently I've been working in Naples Florida with 26-year-old Decyo McDuffie, a gifted singer consumed with absorbing vast quantities of Songbook masterworks, interpreting them through the lens of his hero, Nat Cole. The group of us working with and mentoring him are all in our 60s and 70s. Last week Decyo led us in a Nat tribute in a nice auditorium in Ft. Myers. We got a standing ovation and played an encore.

Crazy, baby!

Invisible Man is one of my favorite books. I've read all the short stories of John Cheever, 5 or 6 Bellow novels (Augie March is in my top 25), All The King's Men and The Heart is A Lonely Hunter, The Natural and A Death In The Family would all be in books I strongly recommend. But I'm a screenwriter and a novelist with an MFA from Columbia, so I suppose I'm an exception.

What I would say is that the 1940s and 1950s are outside of the living memory of pretty much anyone alive, and so the work from that long ago that lives on is exclusively what's truly canonical (I'd guess Invisible Man because of race pre-CRA; Augie March because of Mid-Century Jews, and maybe All The King's Men because of politics. Definitely Citizen Kane, 12 Angry Men, All About Eve, Sunset Boulevard, Vertigo, Paths of Glory, and The Seven Samurai are all heavily referenced movies that most film fans are familiar with, if only because the structure and style of those films defines the decades of films that follow, more than the literature defines the subsequent books.)

If you look at the book sales data, the opposite is the actual problem: contemporary novels are selling worse than any contemporary novels have, and you could probably make the same claim about film. The mania amongst young film buffs around the Criterion Collection and Letterboxd suggests a contemporary obsession with nostalgia (for great work, no doubt!) that is particularly novel to this moment. The problem seems to be not that we are forgetting too much, but that we are not in fact creating enough. If you look forward a few decades from the 40s and 50s--say the Boomers' adolescence and salad days--you'l find that this work is still hugely influential on the culture. PTA is adapting a Pynchon novel for his newest picture; many young film buffs prefer Space Odyssey, Godfather, Star Wars and Jaws to anything contemporary. Philip Roth is still considered the Jewish writer par excellence, Joan Didion the female writer, and James Baldwin the Black writer. As long as some of the audience that experienced the work in the moment is still alive, it is nearly as vital and part of the cultural consciousness as when it was first released.