In the Music Business, 80 Is the New 20

It's never been better for dead and dying musicians

Where did all the new music go?

Check out this update on a major Philly music venue from subscriber Bob Cooper:

I just got their most recent email and over the next two weeks, they are hosting nine shows. Seven of them are "tribute" bands for Pearl Jam, Fleetwood Mac, Sublime, Dave Matthews, Grateful Dead, and Rush. Just two shows are bands playing their own music.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

I checked out the venue’s website, and saw for myself:

Hey, I like the 1980s as much as the next guy with acid-wash jeans and denim jackets hanging in the back of his closet. But if you’re still vibing to that era, I’ve got some painful news for you….

And it’s not just the proliferation of tribute bands. I’ve never seen so many new recordings from dead musicians.

That’s especially true in my favorite genre, jazz. Who needs a time machine—just turn on jazz radio, where it’s always 1959.

Three years ago, I stirred up debate by claiming “old music is killing new music.” I shared alarming numbers—69.8% of tracks streamed were “catalog” songs (defined as more than 18 months old).

That was up from 65% in 2020.

But it’s gotten worse since then. Last week, market research firm Luminate released updated numbers, and they show that old songs now represent almost 75% of streaming.

Half the market is now deep catalog—which is how they describe songs more than five years old.

Rock is the genre where old songs totally rule. But pop and hip-hop are also turning into retro genres for the nostalgic

Not long ago, music was a young person’s domain—record labels courted the fickle, unformed tastes of adolescents and teens. The rest of us found our music in the niches and crannies of the business.

But something has changed. In the 21st century, the music industry has fallen in love with the dead and dying.

Investors have noticed this trend—hence the strange phenomenon that the biggest recent deals in music involve artists in their 70s and 80s.

This is a complete flip-flop from the previous paradigm. Eighty is the new twenty.

Instead of scouting new talent, record labels are digging into their archives to find previously unreleased tracks by the dearly departed. These are flooding the market.

A few are outstanding—but even more of these rediscoveries are lackluster, lukewarm, or just plain lousy.

Many are just old bootleg recordings of live dates. Hence the sound quality is often mediocre or worse. There are few surprises—the songs are usually familiar titles already released by these same artists decades ago with better results.

Or, even worse, the music coming out now was originally rejected by the musicians themselves. Now that they’re dead and gone, record labels can issue these discarded tracks, and hype them as though they are rediscovered classics.

So I’m hardly surprised that musicians are taking precautions while they’re still alive to prevent this from happening.

For example, singer-songwriter Lana Del Rey has announced that she is including a clause in her will to prevent posthumous release of unapproved material.

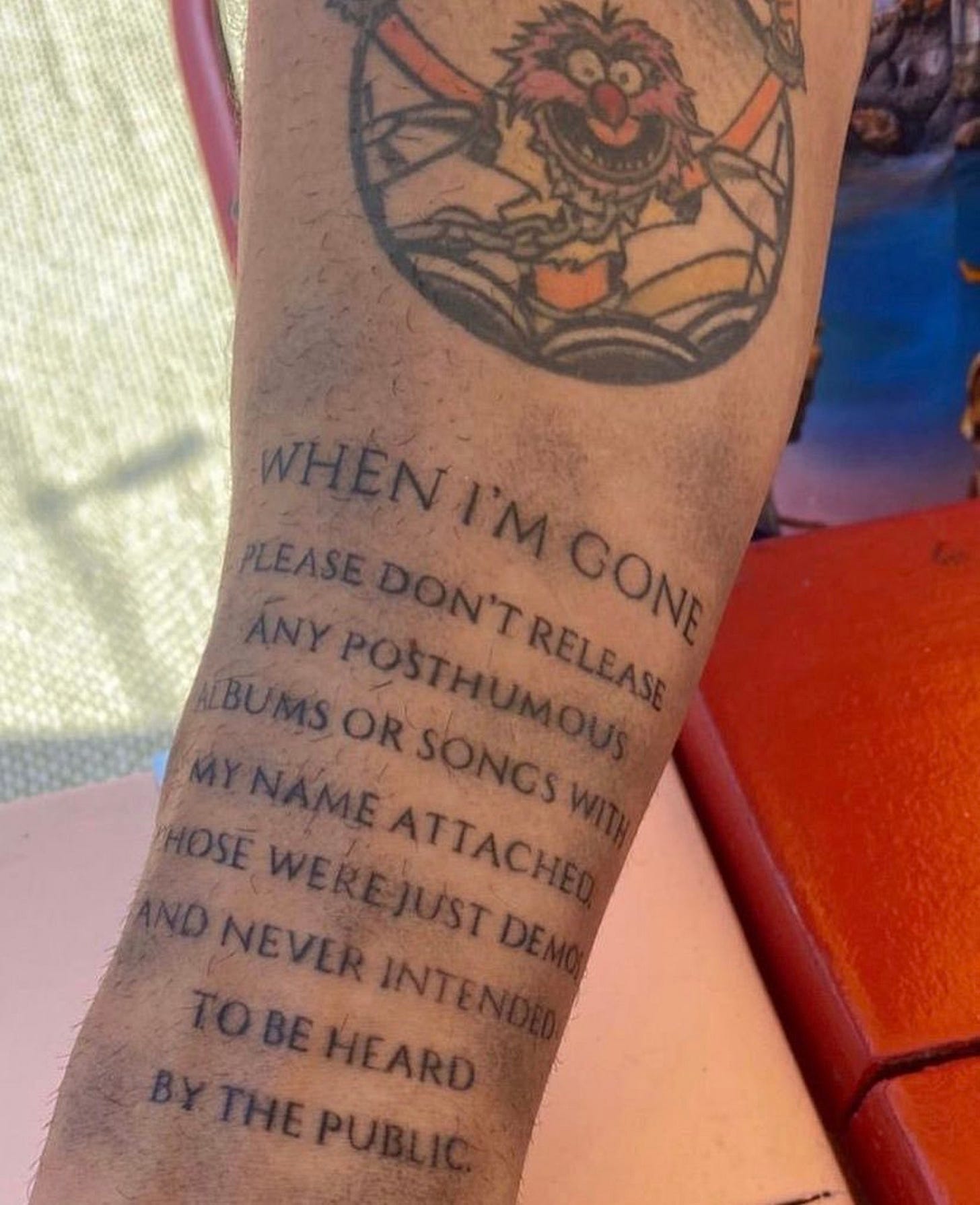

Anderson. Paak has gone a step further—as demonstrated by this photo he shared on social media.

That seems a bit extreme. But can you blame him?

I’m cautious about always deferring to the artist on these matters. The historical record is full of masterpieces that would have been lost forever if we had waited for official approval to release them. The most famous case is Franz Kafka, who asked his friend Max Brod to burn all his unpublished works.

But when Brod became literary executor of Kafka’s estate, he ignored the author’s explicit wishes, and as a result we have The Trial and The Castle—widely acknowledged as defining works of their era. I believe Brod made the right decision and, even more to the point, that Kafka himself would have been happy with how matters turned out.

But for every masterpiece like The Trial, we have embarrassments such as Go Set a Watchman or Michael, the posthumous Michael Jackson album that actually generated a class action lawsuit over its authenticity.

Here’s a discussion thread in which music fans offer their choices for the worst posthumous release ever—sad to say, there’s no shortage of candidates.

If you think this matter is tricky enough already, just wait until the technology for holograms and deepfake music becomes more robust and affordable.

It’s already starting to happen. Clumsy AI resurrections of dead musicians are all over YouTube. Most of them are painful to hear.

Thanks to AI, I’ve also heard Louis Armstrong sing “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” “WAP” and “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” I’m doing you a favor by not supplying links.

But we have only had a tiny taste of the coming era of zombie musicians, raised from the dead to make money for the living.

I heard from someone involved in creating a hologram show featuring a dead female singer, and what I learned horrified me. In this instance, the promoters needed to create the hologram from photos, but there simply weren’t enough surviving images of the deceased—so they hired an actress who resembled her, and used her as a model for their hologram.

In other words, the resulting hologram was a computer construct of an impersonator. Of course, that’s never specified in the marketing materials. Fans think they are seeing something indistinguishable from that artist in the flesh, but they are actually several degrees removed.

And with the advances in deepfake voice technology, these phony constructs can be made to sing any song, no matter how banal or misleading.

Just consider what happens when the cost of this technology drops sufficiently. When it makes it debut, the Elvis hologram plays in a fancy concert hall or perhaps a Vegas casino, but soon this captive King can be forced to sing at every diner, drive-in and dive.

The mind reels at the possibilities: Come see John Lennon singing at a adolescent’s birthday party or Whitney Houston warbling at the Waffle House.

How greedy are the heirs and estates of dead superstars? We will soon find out.

The legal implications here are murky, but the potential is unsettling. I doubt that our legislators will help us—in fact, they will probably do more harm than good, judging by their previous attempts to ‘fix’ the music business.

But a good start would be a voluntary code of ethics, made by the most trustworthy individuals in our music ecosystem, with guidelines on the proper respect due to the artists of the past. Then we can ask record labels and concert promoters to sign on to these precepts.

It’s best to do this now, before business interests based on exploiting the posthumous rights of musicians get much larger and more powerful. If we wait too long, we may find that we’ve replaced a vital and living music scene with a pantheon of the dead.

Re "How greedy are the heirs and estates of dead superstars? We will soon find out."

I've worked with the heirs and estates of authors. The answer is: super fkg greedy, especially the farther from the author an heir is.

Agree with everything stated. But I think another problem (and perhaps a chicken and egg scenario) is the lack of recording studios and the lack of finances for bands to record. The rise of EDM and solo artists has always seemed like a financial one to me — electronic music is cheaper to make than rock or jazz. One of the first things that happened post Napster was labels cut budgets for recording sessions. And much of the recording industry has been decimated; partly by this myth that home recording is just as good. Which is only the case if you write music like Billie Eilish (nothing wrong with that kind of music! But its easier to get one good vocal mic sound at home than do an actual band).

So part of the rise of old music now might just be that people want to hear music performed by a band rather than computer loops and samples — but there’s a huge gap of that in new music, at least in music that isn’t underground.