I Return to Vinyl After 34 Years

But I now see firsthand how the music industry is fumbling this huge opportunity to revitalize its business

Some time around 1988 I abandoned vinyl. I never thought I’d go back.

But I’ve now learned: Never say ‘never’. In fact, our whole musical culture seems to be taking on a decidedly retro flavor—believe it or not, Fleetwood Mac's Rumours, released in February 1977, is still on the chart after 926 weeks—so it sorta makes sense we’re spinning vinyl in 2022. We just need to change a few Fleetwood Mac lyrics.

Yes, we’ve stopped thinking about tomorrow. . . .Yesterday’s here, yesterday’s here.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I was actually a late adopter of CDs back in those distant days. The first time I saw a compact disc was in 1983 at the San Francisco home of a college classmate from an affluent family—her father had purchased one of the first CD players. I looked at the pricey device with curiosity, but had no desire to buy one myself.

Can you blame me if I was slow in embracing the new digital format? I’d sacrificed for my vinyl albums—scrimping and saving, and cutting back elsewhere on my tight student budget in order to indulge myself at the record store. After deducting tuition, room, and board, I had around one hundred dollars per month left for everything else—I cheerfully allocated more than half of it to books and records. So those vinyl discs represented more than just my music collection, they literally embodied my core values, my top priorities, my coming-of-age story.

As a result, I viewed the arrival of the compact disc in the mid-1980s with apprehension and hostility. I even recall an afternoon at my friend Ken Oshman’s house where we did a side-by-side comparison on his ultra-high-end audio system, dissecting the differences between analog and digital music. I remember arguing that the compact disc had a certain sharpness and clarity to the sound, but vinyl offered greater warmth, and a richer depth of field for the listener. I insisted that I could hear the relative positioning of the members of a jazz quintet on vinyl in a way that the CD couldn’t approximate.

Just listen, Ken—can’t you hear that the saxophonist is standing just to the right of the bass player, and the drummer is off to the left, a little farther back. Your compact disc can’t do that.

But a short while later, I found myself running a startup jazz record label, funded by some Silicon Valley music fans. At this point in time, compact discs were a booming business, spurring growth for the whole music industry. Album sales were accelerating every month, and all the demand was for compact discs.

Record stores were opening that only stocked CDs, refusing on principle to sell vinyl. Analog, I got told repeatedly, was dead. Digital was the future. I should have questioned the conventional wisdom—because many of the best decisions in my life came from going against the grain. But I was so immersed in the new paradigm—it actually paid my salary—that I began to waver in my digital resistance.

First I bought a couple compact discs. Then a few more. And after a while, I only acquired CDs. This wasn’t as big of a deal as it sounds—because record stores were now rarely stocking vinyl, especially for the obscure new releases I preferred.

I had no illusions about digital sound. I recognized that it possessed a certain bright unreality, like the aural equivalent of fluorescent lights. But I assumed—wrongly, as it turned out—that the music business would eventually release an even better digital technology. It’s all just a matter of data, no? If you keep on adding more information in those tracks, eventually they sound just as good as, or better than, high-end vinyl. So I switched to CDs, and patiently waited for the next generation.

It never arrived.

What I didn’t realize was that the music industry no longer had any interest in R&D or improving audio technology. They were too busy shipping out CDs by the millions. Just a generation earlier, records labels such as Columbia and RCA had considered themselves tech companies, and funded ambitious projects to improve audio formats. But by the 1990s, the record industry had grown fat, dumb, and happy.

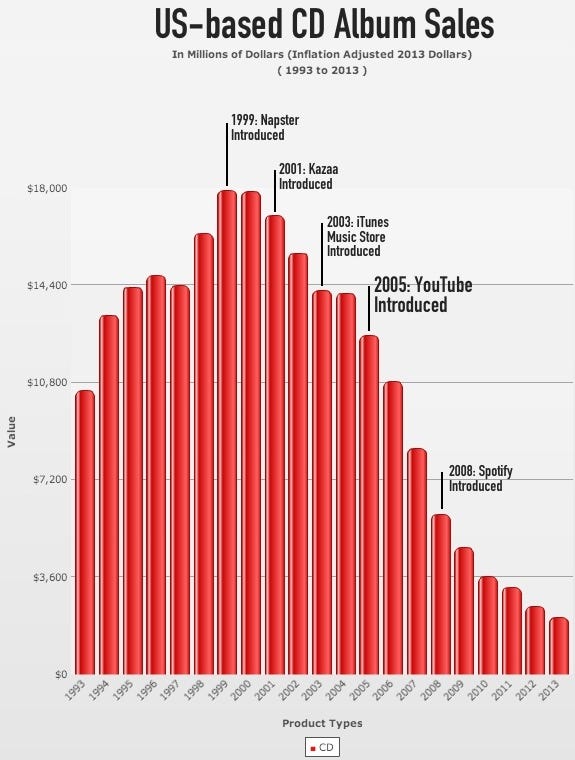

So it’s no surprise that the music business stopped growing in 1999. The arrival of the Worldwide Web, which presented so many growth opportunities, was viewed by the major record labels as a distraction and inconvenience. They could have built their own web platforms, but instead they preferred to do nothing on the web—and threaten anyone who did otherwise with litigation.

They celebrated when their lawyers destroyed Napster—although it would have been much smarter for them to take over control of the platform and run it themselves. But when Apple launched iTunes, they trembled, because Steve Jobs had even more lawyers on his payroll than they did. For two decades, they had put all their faith in lawsuits, and now they had encountered a company that wasn’t about to budge in the face of their threats.

So the labels capitulated. Totally. Online music wiped out the CD, and it happened with extraordinary speed—even before streaming, iTunes did most of the damage.

Even at this late stage, the major labels could still respond with an exciting new physical format for music (more on that below). But that would require vision, commitment, and investment—and the major labels have no capability of mobilizing those things in the new millennium.

I switched to streaming, like so many other music fans. But streaming, as I came to discover, was inferior to CDs in every regard except price. You don’t get liner notes, or photographs, or even decent track information. When I stream an album of contemporary classical music, I often struggle to learn the name of the composer. Or I’ll listen to a hot new jazz track, and have no way of learning the names of the musicians in the band. If I do a search for ‘new jazz’ on the platform, all I get are recordings with the words new and jazz in their titles.

I could go and on.

Many of these problems were obvious years ago, but still haven’t been fixed. It’s almost as if the people behind these streaming platforms don’t really care about music.

At first blush, that seems like an outrageous idea, but is it really? Just look at the people making all the key decision in streaming nowadays—very few of them have backgrounds in music or even come from the entertainment industry. Tech companies (Apple, Google, etc.) call all the shots, and the last thing they worry about is the music ecosystem, which they will happily pollute if they can sell more devices or advertising. Even Spotify, which makes almost all of its money from music, doesn’t like to be a called a music business—they proudly proclaim that they sell subscriptions, not music.

If you doubt it, just check out the “Business Description” in the company’s annual report. Do you see the word music anywhere?

That’s exactly the mindset that created a music distribution system incapable of telling you the name of the drummer, or the composer, or the singer, etc. etc. And if you push these people, and demand a richer experience, they tell you: We can’t tell you the name of the drummer, because it isn’t in the metadata.

Well, duh, then hire a few knowledgeable people, and let them add this information manually to your platform. I once ran a web platform called jazz.com, and with a tiny budget I published detailed personnel and background information on ten thousand jazz recordings over the course of just a few months. This isn’t an impossible task—in fact, it’s easily solved. And if Spotify doesn’t have the budget (hah!), they can crowdsource this effort from fans—who would love to help them fix this mess. But they have to care about the music, or the problem will never get solved.

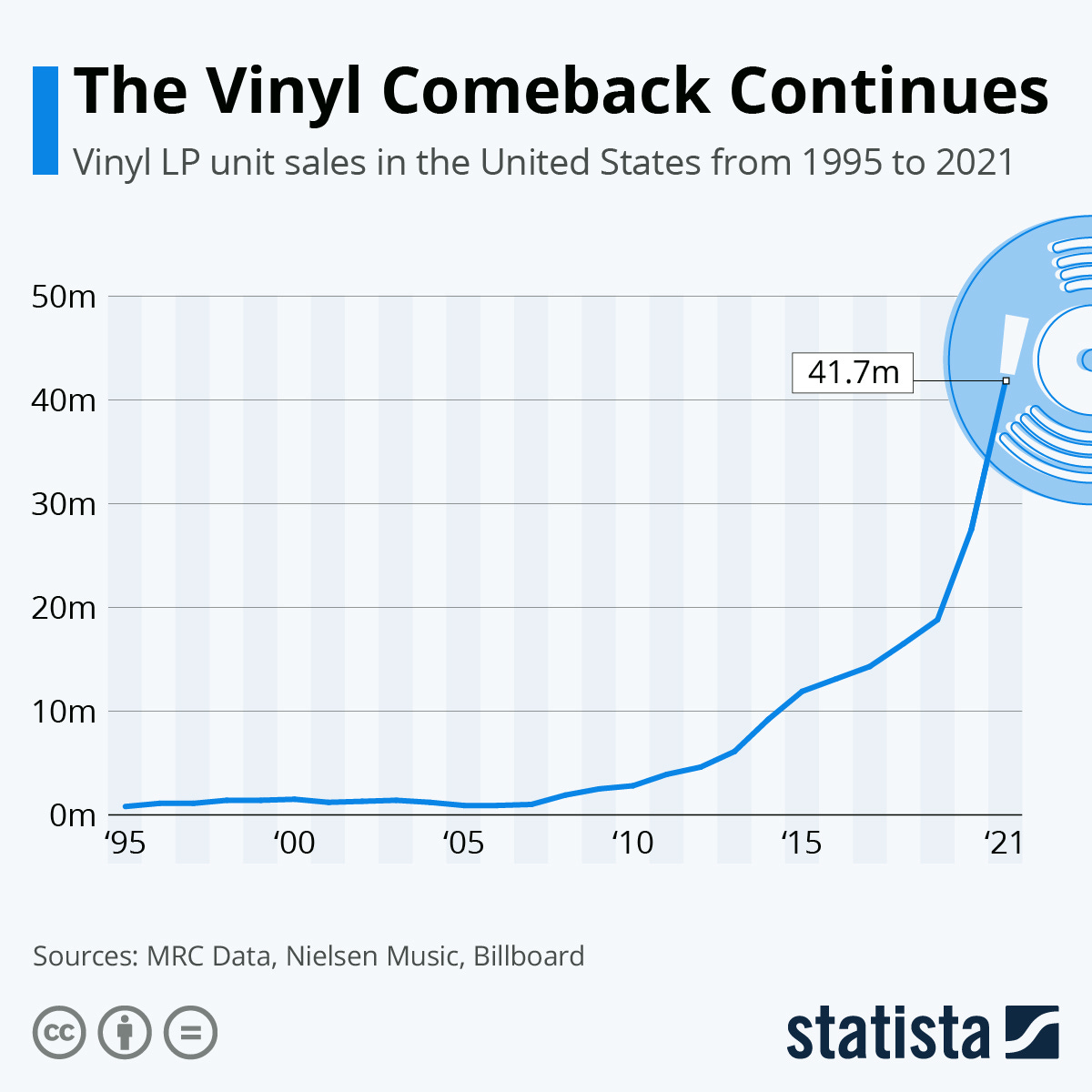

This is one of the reasons why so many people have returned to vinyl. It’s simply a better format. I’ve made the plunge myself.

My wife gave me a modest turntable for my birthday—I’d hinted to her that this might be a welcome gift. A few days later, I made my first vinyl purchase in more than thirty years. The record was Handel’s Concerti Grossi, performed by Trevor Pinnock and the English Concert.

I placed the turntable near my easy chair, and put the needle into the groove of the LP—it’s been a long time since I’ve done that. A second of static, like an invocation, then the music began. I soon fell into a pleasant reverie.

It didn’t take long for me to decide to buy a few more records. Most of them so far have been classical music albums, supplemented by a few vintage jazz releases from the past. I can see that this will get to be a habit.

Clearly I’m not the only one who thinks this. Vinyl is the fastest growing segment of the music business—and it’s not even a close race.

But now that I’ve returned to LPs, I see all the foolish things the music industry is doing to discourage fans from participating in the vinyl revival. And that troubles me.

(1) First, I was shocked at the limited availability of even celebrated recordings—although the vinyl revival has now been happening for years. Most of the titles I want to buy simply aren’t available. And when I do find one for sale, it’s usually a secondhand album that’s more than 40 years old.

The main reason for this is the limited manufacturing capacity for vinyl albums, but that leads to the second music industry blunder.

(2) With few exceptions, record labels have tried to avoid investing any money into manufacturing. So they outsource production of vinyl records whenever possible. This is serious mistake, and it’s driven by bad analytics and pure laziness.

Record labels once knew how to manufacture and distribute physical objects. They’ve forgotten those skills, and really don’t want to be bothered relearning them. Yet the return on investment for vinyl pressing equipment is very attractive. Any spare capacity can be sold at a tidy profit—there’s enough demand to run these machines around the clock. And the vinyl trend has proven that it isn’t short-lived—demand has been growing rapidly for more than a decade now.

The half-assed response of the labels is sad, but also revealing. This decision to sit back and do nothing is why they failed to take control of Internet distribution, and also why they allowed the whole price structure for music to collapse. And now they are showing similar complacency in the face of the one opportunity that could give them a permanent edge over the streaming platforms.

That leads to the third problem with the vinyl revival. . . .

(3) The level of greed is off the charts. Because it’s so hard to make money in music nowadays, the labels have decided to squeeze as much cash as they can from vinyl fans. This is one area where Spotify and Apple don’t call the shots, so why not charge twenty dollars for vinyl? Or maybe thirty dollars is better. Hell, let’s ask for forty, and see who will buy?

In other words, a technology that is 70 years old—and in which labels have invested almost zero additional dollars—is priced as if it’s a hot new innovation requiring billions of dollars in startup capital. This is like taking your old shoes, and trying to sell them for twenty times what you paid for them.

In a market where retro is hot, you might get away with this—at least for a short time. Some of my readers will probably respond: Well, if Taylor Swift fans are willing to pay forty bucks, it’s a perfectly fair price. That may be true, but it’s still a stupid price—because the vinyl revival won’t become a mass market phenomenon at these prices. I’ve spent a lot of time over the years studying the economics of pricing, and will tell you with absolute confidence that what record labels are doing right now will eventually be taught in business schools as a case study in mistaken priorities.

In a market with so much untapped demand, you start with a high price, and then gradually bring it down—meanwhile adding lots of manufacturing capacity. What the music business has been doing is the exact opposite. They make no investments in manufacturing capacity, and this allows them to price gouge, meanwhile discouraging demand and slowing down adoption. As demand continues to outstrip supply, they push up prices even more. The result is a profitable niche market, but the larger opportunity is in creating robust mass market demand.

The current vinyl marketing strategy it’s the exact opposite of what Spotify did. The streaming platforms were even willing to set prices below their total costs in order to accelerate adoption. Smart companies have been doing this for decades. I will remind you that many people insisted that Amazon would go bankrupt in the 1990s because it set prices below its fully absorbed costs. But this actually was how they conquered the retail space. Record labels should have begun pursuing that strategy with vinyl five years ago. Instead they did the exact opposite.

As long as I’m asking the major record labels to do things they will never consider, let me finish with the most important of all.

(4) The music industry could get rich by developing a next generation vinyl format. Let’s call if Super-Vinyl. It would have all of the advantages of the current physical products, but with better audio quality, durability, etc. Maybe it even comes with some digital or NFT twist. Let your imagination run wild.

This is the single biggest opportunity for record labels to take the music business back from Silicon Valley. Spotify and Apple wouldn’t have a clue how to respond to a high tech physical format in music—their business systems aren’t equipped to deal with that kind of competition.

The major labels could change the whole direction of the industry in their favor. But it would require vision, hard work, and investment. That was exactly how vinyl was developed in the first place, back at Columbia Records. It could happen again. The best approach would be a joint venture between several key record labels.

I would support a next generation vinyl-type product. Tens of millions of other people would do the same. Who in the music business is ready to step up and make it happen? I don’t see a single CEO in the industry with the vision and drive to do this, so I’m pessimistic. But I’d love to be proven wrong.

Meanwhile, I’m buying up more 40-year-old virgin LPs.

Great piece! Being just a bit too young to have any nostalgia for vinyl, the thing I REALLY miss are liner notes. For example, discovering Loreena McKennitt's music in the mid 90s and listening to it while reading the thick mini-book-length liner notes, with several paragraphs of backstory on each song was an absolute delight. I mean, these exist somewhere online if you really dig, but it's not the same.

I recently got a few new LPs. They sound amazing - except for the inner groove distortion! I have a nice Dual turntable, and I realize that this type of distortion is just an inherent flaw of vinyl. But it bothers me so much that I don't know if I'll keep buying records or just save up for a fancy streaming box to hook up to my stereo...