How to Commit Murder Inside a Locked Room

Few genres are more preposterous than the locked room mystery, but still I keep on reading

Below is a survey of my favorite subgenre of crime story, the locked room mystery.

The premise is simple. Readers are presented with an impossible crime. A victim is killed in a locked room. There’s no way the criminal could have committed the murder and escaped, yet somehow it happened.

Related Story:

My 13 Favorite Locked Room Mysteries

I can’t deny that the solutions are often bizarre, even preposterous. But I keep on reading these potboilers. I’ll let the rest of you obsess over other puzzles—Wordle or Sudoku or whatever scratches your itch. My fixation is, rather, with a corpse in a locked and bolted room.

In the next few days, I will share another article on the subject—a list of my 13 favorite locked room mysteries. But today I’m focusing on an overview of the genre, and paying tribute to its greatest exponent.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

How to Commit Murder Inside a Locked Room

By Ted Gioia

Ever since Edgar Allan Poe pinned a murder on an orangutan swinging in and out of an otherwise inaccessible window, the locked room mystery has provided more unusual and frankly preposterous plot twists than any other branch of fiction.

I have a fondness for these stories that is hard to justify on their purely literary merits. They emphasize intricate plotting, almost to a ridiculous extent, and sometimes at the expense of the other qualities we seek in fine writing. In many ways, locked room mysteries are more like chess problems or logic puzzles—which I also enjoy—than conventional narratives. But there’s also something magical about these stories. They present an impossible scenario: a crime has happened under circumstances that defy belief. And this fantastic element imparts a flavor of awe and perplexity to the genre that, for me, no other kind of crime story can quite replicate.

If you approach these tales with the proper frame of mind, the ridiculous aspects become sources of delight—no different from the outrageous elements in a play by Ionesco or Beckett. Perhaps we should simply classify the locked room mystery as a branch of absurdist literature, and leave it at that. The entrance of the orangutan is exactly what such a story needs and deserves.

You want spoilers? Let me give you some.

Here are a few solutions to various locked room mysteries—and this is just a taste. The knifed victim in the locked room actually killed himself with a sharp icicle, which melted leaving behind no weapon, merely an unexplained stabbing in a sealed chamber. In another case, a miniature gun is hidden inside the receiver of a telephone, shooting the victim, whose body is found later behind a locked door, apparently murdered while trying to call the police. And how about the time poison gas was stored in a mattress, but only released when the warmth of the victim’s body heated it to the proper temperature—and it has, of course, dissipated by the time the police break down the door of the locked and bolted bedroom.

In another story, a bat flies in through a chimney, dislodges a ceremonial knife, which falls into the heart of the sleeping victim—soon after discovered dead from a stabbing wound inside an impregnable room. Or consider the canopy of the four-poster that turned out to be a cleverly-constructed suffocating device, lowered on to the sleeping victim by means of a mechanical gizmo operated in a secret chamber on the floor above his bedroom—then retracted after the murder, leaving a suffocated corpse inside (you guessed it) a locked room.

I could go on and on. I won’t even begin to list all the variants of disguises, lockpicking techniques, hiding places, acrobatic killers, relocated bodies, etc. that figure in these stories. However, I will give you one piece of advice: the first person to discover the body is usually your best suspect.

When locked room mystery author Clayton Rawson surveyed how this subgenre has evolved over the decades, he could only lament the impossibility of pushing it any further. “The variations on these basic methods of dealing death,” he writes, “have reached fantastic heights: icicle stilettos, rock salt bullets, air bubbles injected into the veins, daggers fired from air guns, tetanus lurking in the toothpaste, and all that huge assortment of concealed automatic mechanisms, the mere description of some of which is enough to scare a person to death — which, incidentally, has also been done!”

If locked room mysteries ever receive the respect they deserve, John Dickson Carr (1906-1977) will become an author of renown, studied at universities and discussed at symposiums. They might even put up a statue in his honor (preferably inside a locked and bolted room). He is the greatest master of this subgenre and, from my perspective, the competition isn’t even close.

Others with greater pedigrees in detective fiction agree in this assessment. In 1981, a survey of mystery fiction experts was conducted to determine the greatest locked room stories, and Carr’s novel The Hollow Man (1935) was picked as the best of all time. Three of his other works were in the top ten: The Crooked Hinge (number 4), The Judas Window (written under his pseudonym Carter Dickson, at number 5), and The Peacock Feather Murders (also written as Carter Dickson, at number 10).

But this only scratches the surface of Carr’s oeuvre, which comprises almost a hundred books written under several names. Alas, many of them are out-of-print or hard-to-find, even as a devoted cult following continues to honor his unparalleled mastery of the locked room mystery almost a half century after his death.

Snobs will tell you that this type of story is little more than a pulp fiction stunt, but Carr stands out from his peers for very rare skills that any author should envy. First, the connecting threads of his plots are as grand as anything you will encounter in highbrow literary fiction. There are so many moving parts in some of his stories that you want to put down the book and sit back in awe that Carr can handle all of them without dropping a single strand. I’m tempted to describe this as a quasi-mathematical skill, but Carr always proclaimed his absolute hatred of math (which he called “the last refuge of the halfwit”)—and there’s even an anecdote about him punching a friend simply because he had mentioned the word algebra.

And, in fact, Carr’s other great writing skill undermines any attempt to brand him as an “analytical” writer. For he had an exceptional talent for infusing his tales with dark supernatural overtones and a marked flavor of sheer weirdness. It’s as if H.P. Lovecraft and Agatha Christie had a precocious love child who combined both their temperaments in a single vocation. That mixture of the ratiocinative and the eldritch makes Carr’s books irresistible—they are like spiderwebs both in their intricacy and the overtones of dark dangers dimly perceived.

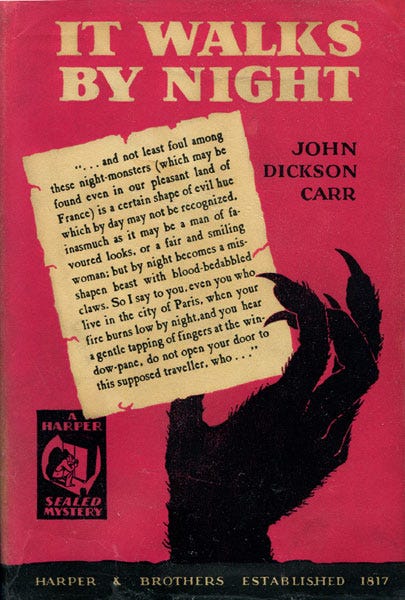

Unfortunately for his biographers, Carr was just as imaginative in reinventing his life story as he was in creating his locked room puzzles. He claimed he was born in Paris, and educated at Harvard College. The truth was less glamorous: he hailed from Pennsylvania and first embarked on his writing career at Haverford College. But before long he channeled most of his creative energy into his work on the printed page. His breakout moment came when Harper & Brothers published his debut novel It Walks by Night in 1930.

They paid him a three hundred dollar advance for the book—equivalent to almost $5,000 in current dollars. The way he secured his publishing deal already testifies to his mastery of the mystery genre. Carr brought the typescript manuscript of his novel to New York, and gave it to a sales rep at the publisher, who read it with great enthusiasm. He passed it on to a colleague, who was equally impressed. They went in tandem to T.B. Wells, the chairman of Harper & Brothers and editor of Harper’s magazine, and wagered a dinner that he couldn’t guess who committed the murder in the story. Wells lost the bet, but Carr got his book contract on August 14, 1929. He was 22 years old.

When the book was released, Harper & Brothers marketed it as “a weird, satanic, terrifying mystery.” The final third of the book was wrapped in a thin, paper seal—and came with a promise that the purchase price would be refunded if the book was returned with the seal unbroken.

Few things were more upsetting to John Dickson Carr than critics who harped on the absurdity of the ‘solutions’ to the great locked room mysteries. “Call the result uninteresting if you like,” he grumbled, “or anything else that is a matter of personal taste. But be very careful about making the nonsensical statement that it is improbable or far-fetched.” He adds: “If a man offers to stand on his head, we can hardly make the stipulation that he keep his feet on the ground while he does it.”

At one point in the 1950s, Carr bragged that he had come up with 83 different solutions to the locked room mystery—but he was still in mid-career at that point, and no doubt continued to add to his deep bag of tricks with each passing year. To his way of thinking, the locked room story was akin to the conjurer’s trick, whose goal is to mystify, and could rely on virtually any expedient in order to produce that effect. He lamented the fact that the magician gets to keeps his techniques secret, while the mystery writer must reveal all of them in the final chapter. This almost invariably produces a deep sense of disappointment in the reader. “We expect too much,” he explains. “You see, the effect is so magical that we somehow expect the cause to be magical also.”

Carr may be the Michael Jordan of this type of fiction, but as with any kind of puzzle, the locked room mystery has continued to attract masters who, even in the face of all these precedents, still aim for grander and more elaborate effects. The days are long gone when an angry orangutan could impress the connoisseurs of the locked room mystery. Even the most famous mystery writer of them all, Arthur Conan Doyle, took a similar tack in “The Adventure of the Speckled Band”—which he claimed was his favorite story featuring the beloved sleuth Sherlock Holmes. Here a snake fulfills a similar role as the swinging primate in Poe’s tale. But a half century later, when we arrive at Carr’s The Hollow Man, the “explanation” of how the crime happened requires a full 25 pages. And in Shoji Shimada’s The Tokyo Zodiac Murders (1981), the author identifies the murderer with more than sixty pages left in the book—the remainder explaining not only how the murder took place in a locked room, but also the method the victim used to kill seven women after his own death.

This is virtuosity, no matter how reluctant you are to assign that word to writers of potboilers. Has any administrator every juggled with timelines so complex? Has any battlefield tactician had to overcome so many obstacles on such inhospitable terrain? Sometimes I feel I need to construct a GANTT chart just to understand the explanation at the end of some of these novels.

The locked room concept possesses such inherent appeal that it has even managed to wiggle its way outside of the genre fiction pigeonhole (a kind of mental locked room in the publishing world mindset, might I say?) and into other narrative forms. There’s a whole video game market built on escape games, a kind of reversal of the murder mystery story where getting out of the room is the way to avoid murder. Isaac Asimov draws on the locked room concept for his science fiction novel The Caves of Steel. In Umberto Eco’s Baudolino, a picaresque postmodern tale set in the late twelfth century, our semiotician author uses the locked room device to explain the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. The Emperor’s vassals are so befuddled by this that one even exclaims (in ironic judgment on the whole subgenre): “Human folly has imagined horrific crimes, from Cain on, but no human mind has ever been so twisted as to imagine a crime in a locked room.”

All in all, the authors who have tackled the locked room concept include some of the most creative minds of the last two centuries. But these others look like dabblers compared to John Dickson Carr, who not only focused his magisterial skills on the subgenre, but made it a major focus of an entire career. Kingsley Amis, himself a master of both literary and genre fiction, once lamented that Carr had “received the highest praise without ever becoming either a popular success or a highbrow fad.” Then Amis added: “Words like ‘gripping’ and ‘absorbing’ should have been allowed to remain in the womb of language until the advent of Carr/Dickson.”

Amis wrote those words 40 years ago, but not much has changed since then. Except that John Dickson Carr is far less known today, and bookstores are even less likely to keep his novels on the shelf. Much to my disappointment, there’s not a single one available for sale at any book retailer in my neighborhood—every book of his I own I had to purchase over the Internet, typically a secondhand, dogeared copy because new editions haven’t been issued in decades. But I wouldn’t be surprised if this changed at some point, maybe when these books start entering the public domain in a few years.

But why do we need to wait? The hunger for good storytelling hasn’t gone away, and media mega-corporations will invest millions on turning a good plot (or even a not-so-good one) into a film or streaming TV series. And Carr’s plots are as well constructed as anything you will find, with plenty of suspenseful atmospherics just waiting for screen adaptation. My hope is that, before too long, some deep-pocketed producer will figure this out. In the meantime, the books are waiting there for anyone who cares to savor their magic.

Thank you Ted for bringing this murder mystery to light. John Dickson Carr mysteries are next on my reading agenda.

The way you write about John Dickson Carr reminds me of how a few people have written about Patrick O'Brian. So much to read, but your life is blessed by reading "Master and Commander" and the many sequels.