How Songs Created Western Rational Thinking

And Socrates sends me on a mad chase into the wild world of musical dreams

Today I’m sharing a section from my new book Music to Raise the Dead.

You can only read this book on Substack. It’s a special feature for subscribers. I’m publishing one chapter here per month.

Each installment of the book can be read on its own. But if you want to go back to the beginning or check out previous chapters, click here.

Today, I reveal how songs served as the foundation for Western rationalist and logical thinking. If you were putting this into a flow chart, it would look something like this.

In the previous installment, I showed how the great pre-Socratic thinkers—Parmenides, Empedocles, Pythagoras—were actually musicians whose vocation was centered on their songs. Today I focus on the next stage in this hidden story, namely the amazing moment in ancient Greece, when Socrates established philosophy as a musician’s vocation.

This has significant implications. And the deeper we dig into this, the more surprising they are.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Can Songs Actually Replace Philosophy? (Part 2 of 2)

By Ted Gioia

When I first studied philosophy, the course began with Socrates—he was the originator of Western rationalist thinking, or so I was told. You can draw a direct line from him to analytic logic and the codification of a scientific worldview.

But where did Socrates get the idea of philosophizing? Strange to say, he got it from music.

They never taught me that in philosophy class. They never taught me it music class. I wonder why not.

Just take a look at Socrates’s own account of his vocation, as related by Plato. “In the course of my life,” Socrates explains, “I have often had intimations in dreams ‘that I should make music.’”

This is an unexpected revelation. And he continues:

“The same dream came to me sometimes in one form, and sometimes in another, but always saying the same or nearly the same words: Make and cultivate music, said the dream. And hitherto I had imagined that this was only intended to exhort and encourage me in the study of philosophy, which has always been the pursuit of my life, and is the noblest and best of music.”

Socrates speaks these words in the final hours of his life, as documented in Plato’s dialogue Phaedo. And here, after a dramatic declaration that he has always viewed philosophy as a type of music, he expresses anxiety that he may have misinterpreted his dream revelations.

“The dream was bidding me do what I was already doing….But I was not certain of this, as the dream might have meant music in the popular sense of the word.” He worries about this possible misstep—which might have been a grave error. So Socrates decides to spend his final days making songs.

“I thought that I should be safer if I satisfied the scruple, and, in obedience to the dream, composed a few verses before I departed.” His first effort on this new path was a hymn—the traditional way of invoking a deity or divine source of inspiration.

This is one of the strangest passages in the entire history of Western thought—although one that hardly gets any attention. We need to give it due consideration, but before proceeding with Socrates, we must take a brief intermission. We have to address a larger and intensely relevant question: namely, why are visionary dreams so often connected to songs?

We have encountered this connection before—in our studies of vision quests and hero’s journeys—and will do so again (repeatedly!) in later pages. But here it shows up in the least likely setting. Socrates, the progenitor of rigorous Western thinking, tells us that his true vocation was not a matter of logical propositions, but related to dreams and music.

How do we deal with this?

Was Socrates a victim of superstition, like so many of his predecessors? Are his views on this matter just more mystical balderdash? Or is the linkage he proposes between dreams and music still relevant today.

To answer this question, I reached out to professionals in the music world and asked them to share their own experiences about dream-inspired songs. I knew of a few examples already, and suspected there might be many more, but nothing prepared me for the avalanche of responses I received—which continued for weeks. More than a hundred people eventually responded to my query, and the intensity and immediacy of the stories they shared convinced me that I had struck a raw nerve.

I had asked a question rarely discussed within the dominant institutions of the music world. Dreams aren’t dealt with at music conservatories, or in textbooks on composition, or inside the offices of music industry execs. But, as I soon found out, musicians themselves take dreaming very seriously. They convinced me that powerful experiences of music transmitted in a dream state, far from being a primitve practice from a discredited past, are surprisingly common even in today’s commercial music.

I reached out to professionals in the music world and asked them to share their own experiences about dream-inspired songs….Nothing prepared me for the avalanche of responses I received.

Not only do songwriters give credit to dreams for their music, but these experiences often result in their most successful songs. Paul McCartney claims that the melody to “Yesterday” came to him in a dream—on waking he rushed to the piano to play it before he forgot what he had heard. The resulting song became the most widely recorded Beatles composition, with more than two thousand cover versions. In 1999, “Yesterday” was still so popular—34 years after its initial release—that it won a BBC poll as the best song of the 20th century.

And something similar happened shortly before the Beatles broke up. McCartney now had another dream—in which his dead mother appeared to him, and told him to “let it be.” This eerie vision again resulted in one of the bestselling and most impactful and popular songs of the century.

And the same thing happened with the Rolling Stones—Keith Richards claims he wrote “(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction” in his sleep. He actually recorded it on a cassette player during the night, and had no recollection of doing so in the morning. The catchy guitar riff on the tape was followed by the sounds of snoring, as Richards fell back asleep. But the result was not just the band’s biggest hit to date, but one of the defining anthems of rock music.

Similar stories could be told about Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze,” Sting’s “Every Breath You Take,” Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are,” Carl Perkins’s “Blue Suede Shoes,” and many other familiar songs. Go take a look at Bob Dylan’s collected works, and count how often he refers to dreams. Roy Orbison even gave the title In Dreams to the album compilation of his greatest hits in deference to this source of inspiration.

Is all this mere coincidence?

Sometimes the stories told about dream-inspired music defy belief.

Bob Weir, of the Grateful Dead, insists that his bandmate Jerry Garcia, after his death, appeared to him in dreams to convey song ideas.

Carlos Santana believes that the Mona Lisa—yes, the woman in the painting—appeared to him in a dream and transmitted lyrics.

Patti Smith wrote a song after dreaming that Jim Morrison of the Doors rose as a stone angel from his grave.

Johnny Cash tells how Queen Elizabeth helped out with a song while he was in a dream state.

The stories are endless, and endlessly bizarre. But no one can dispute the results: the bestselling artists of modern times tell of amazing music transmitted to them, again and again, during their hours of sleep.

And this is just a quick overview of modern rock. An inquiry into dream-inspiration in classical music would involve us in a long account covering the entire history of the idiom, from the medieval songs of Hildegard of Bingen to the modernistic compositions of Igor Stravinsky and beyond. My correspondents have provided me with numerous examples from other genres, too many to share here.

After I asked friends about dream songs, music critic Andrew Gilbert decided to test out the concept with his next interview subject, Indian tabla master Zakir Hussain. Gilbert mentioned my research to Hussain, then asked if he had ever received inspiration for a piece of music while in a dream state.

Hussain responded with an extraordinary story, captured on video—where he tells of returning to the home of his dead father Alla Rakha (1919-2000), one of the great innovators in Hindustani classical music, and learning compositions from him in dreams.

A few days later, I was speaking to Chris Brubeck on the occasion of the centenary of his father, jazz icon Dave Brubeck. When the subject came around to dreams and music, he too had many stories to share. Perhaps most striking was the account he gave of his father’s work on a musical mass. Dave had almost completed the work, but one gap remained—he needed music for the “Our Father.” “He went to sleep at our house,” Chris explained, “and the music came to him in a dream. And it was one of the most perfect things he had ever written. The experience was so powerful that it spurred a spiritual conversion in his life.”

Here, as in so many other instances, a decisive moment of transformation is mediated by a song. When I tell people that music is life-changing, they think I’m speaking metaphorically or symbolically. But I’m dead serious about all this. This book has many examples—but I can only scratch the surface here. More than a few of my readers have experienced this firsthand. Other haven’t—not yet!—but will.

Despite all this, music pedagogy doesn’t pay much attention to dream time. Perhaps it should. My research suggests that musicians themselves are often too embarrassed to raise the issue—although they have important things to say when questioned directly about dream music. In this regard they are not much different from the Native American practitioners of vision quests, who often prefer to keep private the sources of their inspired songs, and sometimes only share information after intense interrogation from researchers.

Who can blame them? The whole subject of visionary dream songs seems tainted by its occult nature. But more to the point, anyone who relies on inspiration from the muse (or from other mysterious sources), and receives it in such uncanny ways, fears losing such a powerful and fragile connection with propitious forces. Researchers into shamanism learned this long ago. The most powerful songs can be too important to share or discuss.

But, sometimes, the researcher won’t even ask.

I have been guilty of these lapses myself—even when vital information was staring me in the face I was incapable of grasping it. I was recently looking through my research notes for my book on the Delta Blues, and I see again and again how my sources were offering me information about dreams and visions. But I had zero interest in the subject, and would pass over these remarks. They seemed irrelevant to me, perhaps even boring.

For example, people who spent time with the great Delta blues singer Booker “Bukka” White (1906-1977) in his final days, said I should look more deeply into his “sky songs.” White claimed that these songs originated when he reached up into the sky, where the music was granted him by his muse. White actually recorded two albums named Sky Songs, after his rediscovery by blues fans in the 1960s. Yet when I was researching White’s life and times, I was far more interested in other details—his incarceration, his life on the road, and especially his rise to fame, largely on the basis of 14 tracks recorded in a single day in 1940. Those seemed like the more relevant subjects for a music historian.

But I ought to have dug more deeply.

Even his famous 1940 session should have stirred my curiosity. The historical record makes clear that White wrote these deeply moving songs, which rank among the most intense works in the whole history of the blues, over the course of just two days. I should have asked more questions about how this miracle happened.

How can you possibly compose 14 timeless songs in just a few hours? That’s a far more important matter than any merely biographical inquiry. If I had taken this subject seriously, my blues research would have taken me up into the sky, and the otherworldly visions that made these historical recordings possible. But, back then, that wasn’t a journey I was prepared to take.

Let’s now return to the case of Socrates, where we discover an uncanny similarity to the stories we have just heard about rock stars and shamans. Here we learn that the vision quest and its songs assert their preeminence at the very beginning of the Western philosophical tradition. We have already heard Socrates’s own testimony for this, as communicated by his student Plato; and any scholar who wants to dismiss his comments as the sentimental ramblings of an old man has to deal with the awkward historical fact that Socrates was executed for precisely this allegiance to the divine voice that spoke to him in dreams.

The charges against Socrates, at his trial in Athens in 399 BC, included these two specific crimes: (1) He failed to honor the same gods as his fellow citizens and: (2) He introduced new deities of his own. Socrates defended himself against these accusations, but he refused to deny his relationship with a personal deity (or daemon) that communicated with him privately.

This is, of course, the same muse we encountered back in Chapter 2—when we looked at the origins of the musical conductor. Only now it’s a famous philosopher who not only tells the same story, but puts his life at stake by doing so.

It’s a “divine or spiritual sign,” he admitted. “This began when I was a child,” he explained. The voice continued to manifest itself over the years, warning him against certain actions. As part of this same public testimony, Socrates clarified that his distinctive style of questioning—the famous Socratic method, still practiced today as the most venerable and respected path towards wisdom—had been “enjoined upon me by the god, by means of oracles and dreams, and in every other way that divine manifestation has ever ordered a man to do anything.”

Socrates may have died because he listened to this voice, but that hardly discouraged his disciples from following his dangerous example. In fact, Platonism never abandoned the supernatural beliefs that presided at its birth. Almost five hundred years later, the esteemed Greek biographer and essayist Plutarch continued to focus on this peculiar detail in the life of Socrates. “Are we to call Socrates’ personal deity a lie, or what?” asks Theocritus, in Plutarch’s On Socrates’ Personal Deity.

“Whenever he was in situations which were opaque and unfathomable by human intelligence…his personal deity invariably communicated with him and made his decisions inspired.”

And more than two hundred years after Plutarch, the most famous Platonists of the era promulgated a new series of texts, known as the Chaldean Oracles. These were a philosophical hymn or poem in hexameter allegedly transmitted during a dream state. This work, which only survives in fragmented form, has even been called the “Bible of the Neoplatonists.”

But this was hardly an isolated example. Macrobius’s Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, which appeared around 430 AD and builds on the account of a journey to heavenly realm preserved by Cicero, drew on this same tradition of connecting wisdom with visions. Even at this late date—more than 800 years after the death of Socrates—leading thinkers continued to consider dreams as more reliable sources than the rationalistic cogitations most of us associate with philosophic inquiry.

These sober Neoplatonic philosophers have left us with strange texts, referring to rituals that possess an uncanny resemblance to the rites of sorcerers and witches. Scholars of the current day are troubled by the invocations used at these ceremonies, which seem little more than “a random selection of so much vocal gibberish.” But closer examination reveals recurring patterns in this apparent glossolalia, suggesting that a hypnotic beat may have turned these strange words into the same kind of channel to alternative states we have already described in conjunction with shamanism.

“By rhythmically chanting these sounds,” surmises Ruth Majercik, scholar and translator of the Chaldean Oracles, “the adept was able to effect the proper conjunction with the god.”

Similar promises can be found in virtually every belief system of the ancient and medieval world. We find it in Gnosticism, Hermeticism, the Greek Magical Papyri, and of course in Christianity, and other religious contexts, spanning everything from the Merkabah mysticism of Judaism (with its fixation on chariots very similar to what we’ve seen in Parmenides) to the famous night journey described in Chapter 17 of the Koran.

But what makes the Chaldean tradition so unusual is that it may have promised an actual conjunction with the spirit of Plato himself, who had been dead for centuries. Here, as in so many other contexts, the dividing line between philosophy and mysticism disappears, and song and rhythm provide the means to break down the boundary.

A full account of the role of music and visions in the annals of philosophy is beyond the scope of this book. But some readers may have a simple question: namely, when did philosophy finally abandon these superstitious beliefs? When did the discipline give up magical/musical thinking and operate on the firmer ground of human reason?

The short answer is: Never.

Even a cursory account reveals how music continued to haunt the great philosophers:

Marsilio Ficino, the most influential Platonic philosopher of the Renaissance, composed hymns in the manner of Orpheus. He aspired to a ritualistic connection with divine powers surprisingly congruent with what we found in the Derveni papyrus back in Chapter One.

We find the same thing during the Age of Enlightenment, where this faith in transcendent song shows up everywhere from the opera libretti of Voltaire to the “musical dialogue” of Diderot’s Le Neveu de Rameau.

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, Schopenhauer was forced to concede, in the course of his massive work The World as Will and Representation, that music, not philosophy, “expresses the innermost nature of all life and existence.”

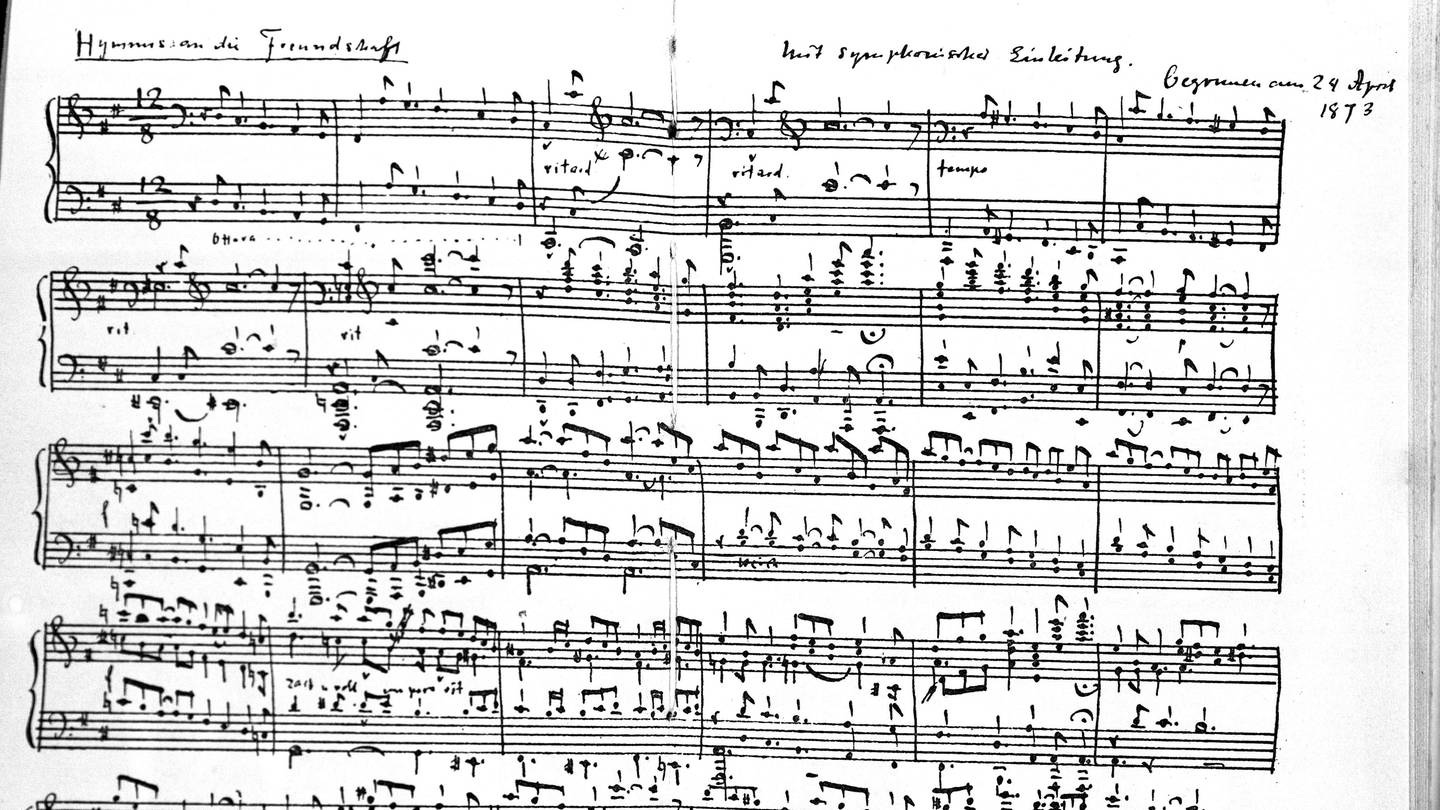

Nietzsche had a similar fixation on music as a path to transcendence. As a youngster he speculated that it “leads us upwards,” and chastised composers who abandoned this responsibility. “There is no work by Nietzsche in which music is not more or less present,” asserts his biographer Georges Liébert.

In fact, three of Nietzsche’s books deal with musical composition as a central concern. To some extent, music set the blueprint for his entire approach to philosophy, and he often described his texts as though they were pieces of music (just as Socrates had done). The Genealogy of Morals was envisioned as a sonata, and Thus Spoke Zarathustra as a symphony.

Nietzsche, also like Socrates, decided to compose his own musical works. He failed to achieve the renown he coveted in this field, yet never lost his obsession with the power of song. In his final years he offered up his most concise evaluation of the art, in an oft-quoted aphorism: “Without music, life would be a mistake.”

We could tell similar stories about Kierkegaard, Spengler, Bergson, Wittgenstein, Sartre, and other seminal thinkers. Sartre even resolves his philosophical novel Nausea with an extraordinary incident in which his protagonist Roquentin cures his existential angst by listening to a jazz record—a stunning conclusion to a dark and deep narrative. Even if they disagree on the destination, each of these philosophers concurs with Socrates’s sense that music provides something essential for the journey. Songs leads to wisdom that texts cannot reach.

There’s only one way for philosophers to avoid taking this journey, and that’s by restricting their ambitions. Instead they settle for banal and worthless goals. When I studied philosophy at Oxford, a generation ago, a joke circulated among the students. A famous analytic philosopher, so the story went, promised to give a lecture on the “Meaning of Life,” but when eager listeners assembled to learn this proffered wisdom, they found that the actual subject of the talk was merely the meaning of the word ‘life’.

In fact, I’m not sure this was just a joke. It might have been an account of an actual lecture that took place in the university’s hallowed halls. Given the narrow focus on linguistic analysis that passed for philosophy in that setting, just such a fruitless enterprise was actually the norm. Most of my studies, back then, took place under the guidance of a philosophy professor who had just published a 500-page book on the philosophy of grammar, and he and his colleagues worked zealously to dissuade students from reading Sartre, Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, and others who sought for a meaning in life that couldn’t be reduced to meticulously constructed propositions.

Text had finally triumphed over sound—but at what cost?

Too often the dominant rationalist worldview demands that we choose between music and texts. You can even trace this back to Plato, too—who both admires music but often seems to fear it. And he had good reason for that. Although he gained renown as a philosopher, musicians were his rivals. You might even call them competitors in the wisdom business.

But you don’t need to choose. You can have the benefits of both the words and the music.

What happens when you combine words and music in a particularly charged setting where some kind of transcendence is pursued (and sometimes actually achieved)? We have a word for this intersection: it’s called a ritual. But other people might describe it as a rock concert, or a rave, or a visit to a jazz club.

In ancient times, mystery cults promised a similarly democratizing experience—and attracted huge numbers of adherents. Perhaps a person could reach the same destination without the benefits of music or ritual, merely by studying the right texts in a philosophy class. But why would anyone discard those time-honored musical assists for the journey? They have proven their efficacy in the past, and will again in the future.

This approach is especially relevant in the current moment, because philosophical thinking in the postmodern age increasingly takes on the guise of a discourse about discourse. Call it what you will: deconstruction, the proliferation of epistemes, the dominance of simulacrums, language games, radical hermeneutics, or whatever. Its names, like the demon’s, are many. But these are not the journey, rather a self-satisfied proclamation of the dead-end, albeit this cul-de-sac is celebrated in many different clever and impressive ways.

The fact that any escape is still possible, at this late stage of history, is amazing to consider. But somehow an escape path does still exist in those realms of ritual and music, miraculously immune to this emaciated theorizing. The fact that they remain immune is testimony to the miracle and to their lasting power.

Let’s summarize what we’ve learned in this chapter.

(1) The earliest conceptual thinkers in Western culture operated within the musical quest tradition. They often conveyed their ideas in the hexameter associated with the hymns of Orpheus and other sung works drawing on divine inspiration.

(2) The innovations of Parmenides, Empedocles, Pythagoras, and other philosophers who laid the groundwork for Western rationalism cannot be understood unless we grasp the shamanic and musical aspects of their activities—which stubbornly resist reduction to mere texts.

(3) Dreams, visions, and trances were part of this tradition from the start and (as with the Native American vision quest), often involved aspects of rhythm and music.

(4) Even Socrates—venerated as the key figure replacing superstitious beliefs with rational, philosophic thinking—relied upon visions and inspiration from his tutelary spirit. This muse was also the source of his Socratic method, which remains the basic foundation for all philosophic inquiry. By his own admission, Socrates viewed his entire vocation as a kind of musical practice.

(5) The death penalty imposed on Socrates by the citizens of Athens was specifically due to charges that he relied on this “private daemon” for inspiration. Other “philosophers” met violent deaths, and for similar reasons—their songs and muses put their lives at risk.

(6) The punishment of Socrates instigated a long tradition of cleansing culture and intellectual life of its musical quest elements—a process that has never wholly succeeded, because the quest remains of essential value to both art and philosophy.

(7) Philosophers never completely abandoned music. From Plato to Sartre and beyond, they have repeatedly turned to songs in search for powers and potencies mere words cannot achieve.

(8) Among musicians too, the quest has been marginalized; but a careful inquiry reveals that even in the modern commercial music business, artists repeatedly rely on dreams and visions for inspiration—and these have produced a surprising number of their most successful works.

(9) Music fans instinctively grasp this, and often search for wisdom in their favorite songs, or even define their values and lifestyles on the basis of their musical experiences.

(10) These considerations validate our approach here, namely treating music as a source of visionary inspiration. Philosophers and musicians both knew this in the past, but have mostly forgotten it. The loss has been incalculable in both vocations. To some extent, the visionaries in each generation—both among musicians and philosophers—have to rediscover the pathway on their own.

The goal of this book is to aid in that process of rediscovery.

[Click here for the next chapter of Music to Raise the Dead: “Were the First Laws Sung?”]

FOOTNOTES

Socrates’s own account of his vocation: This and below from Phaedo, translated by Benjamin Jowett, in Plato, The Republic and Other Works (New York: Anchor, 1973), p. 492.

Gilbert mentioned my research to Hussain: The video, released in November 2020, can be found at this link. It’s also embedded in the text above.

A few days later, I was speaking to Chris Brubeck: Comments by Chris Brubeck, from interview with author, December 5, 2020.

This began when I was a child: Plato, Apology, translated by G.M.A. Grube in Plato: Complete Works, edited by John M. Cooper (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997), p. 29.

enjoined upon me by the god: Ibid., p. 30.

Are we to call Socrates’ personal deity a lie: Plutarch, Essays, translated by Robin Waterfield (New York: Penguin, 1992), pp. 319-320.

a random selection of so much vocal gibberish: This and below from Ruth Majercik, The Chaldean Oracles, Second Edition (Gloucestershire, UK: Prometheus, 2013), pp. 25-26.

Schopenhauer was forced to concede: Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, translated by E.F.J. Payne (New York: Dover, 1958) Vol. II, p. 406.

Nietzsche had a similar fixation: Julian Young: Friedrich Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 37.

There is no work by Nietzsche: Georges Liébert, Nietzsche and Music, translated by David Lellauer and Graham Parkes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), p. 1.

Without music, life would be a mistake: Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, translated by Antony M. Ludovici (London: Wordsworth, 2007), p. 9.

Incredible. Mind stretching. I'm anxious to have this book as a hold in your hand printed bound book so I can better read it, highlight in it, see it on the shelf, others see it in my hand, hold it up on camera and more. Print the book. I'm loving this!

I can't say I've had a dream directly inspire a song (yet!). However, I did have one situation where I was able to solve a challenging computer programming problem in a dream.

I woke up and could still see the solution, wrote the code to implement the algorithm, and it worked perfectly.

Our subconscious minds are far more powerful than we are normally aware of.