How Sigrid Undset Went from Secretary at an Engineering Firm to Nobel Prize Winner

I look back at a sadly neglected novelist and her literary masterpiece from 100 years ago

Back when I launched The Honest Broker in April 2021, I promised (or warned) that I would break the rules and cover unusual subjects.

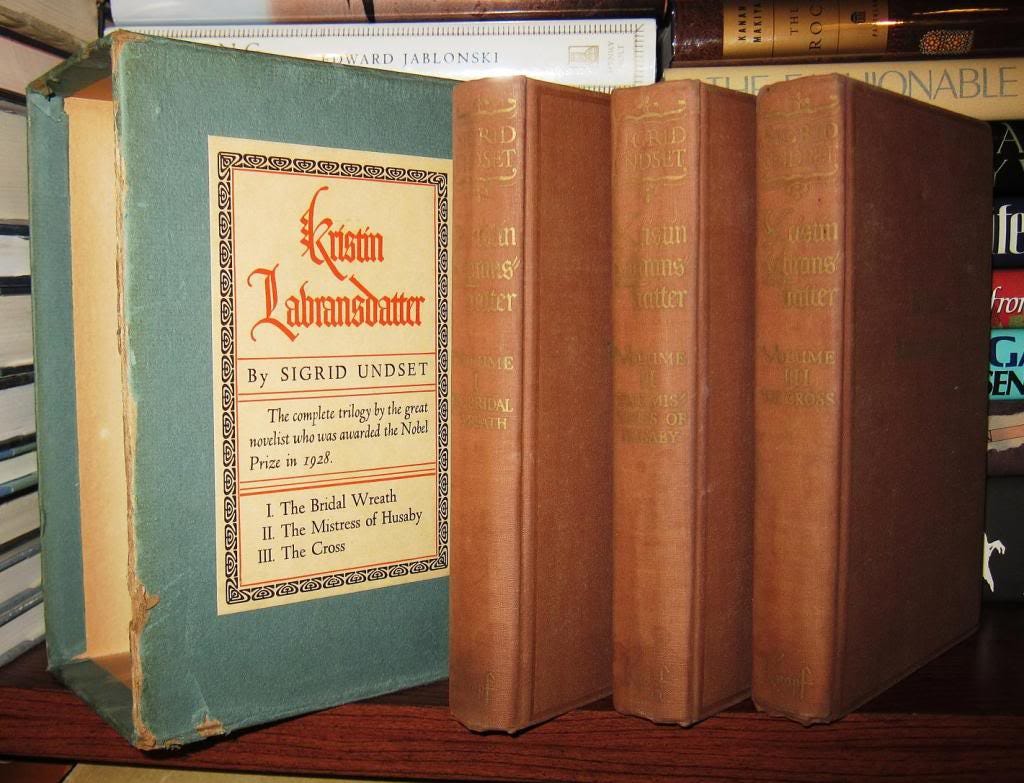

And just to live up to that promise, I’m reviewing a 100-year-old book that almost nobody reads. And for a very good reason—it’s an immense Norwegian novel filling up more than 1,200 pages over three big volumes. The book has a cumbersome title no New York editor would allow in the current day, and the plot is dauntingly complex.

You have my permission to quit at this point and check out some TikTok videos.

Hmm, some of you are still here. So let me tell you happy few (as Shakespeare would call you) that I love this bulky novel, Kristin Lavransdatter by Sigrid Undset.

Undset was the daughter of an archeologist who died when she was just eleven years old, and she never attended college—that simply wasn’t an option back then. Her highest level of education was a year at secretarial school.

After completing her vocational course at age sixteen, Undset was a capable typist. This got her a job as secretary at an Oslo engineering company. For the next ten years, she worked in this same office, relying on her modest income to support her widowed mother and younger sisters.

Undset might have spent her whole life as a secretary—a job she disliked. But she dreamed of becoming a writer.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Sigrid Undset was an unlikely literary star. Modernist themes were on the ascendancy in those days, but she wanted to write medieval romances. So at night, after work, she researched her subject, studying the sagas, old ballads, and chronicles of the Middle Ages.

You might say she lived in the past. Or in a fantasy world of her own creation.

But Undset wanted to deal with these kinds of tales in a brutally realistic manner. She started writing stories where, in her own words, “everything that seems romantic from here—murder, violent episodes, etc. becomes ordinary—comes to life.”

Her first novel was rejected by publishers. But her second book got noticed—and caused a scandal. The opening line announced: “I have been unfaithful to my husband.” The book got denounced for immorality, but sold well. (Are you surprised?) By the time of her third novel, she was making enough from writing to leave the engineering office behind.

At this stage, Undset embarked on an ambitious multi-volume novel that is now her best known work. Kristin Lavransdatter is seldom read nowadays, especially outside of Northern Europe, but it deservedly earned Undset a Nobel Prize in Literature in 1928.

Undset, for her part, later donated the gold medal from her Nobel Prize to support Finland’s war effort in the face of Stalin’s 1939 invasion. Her books were banned by Nazi Germany, and she soon had to flee to the United States, where she lived in Brooklyn Heights, New York from 1940 to 1945.

Here she rented a small apartment at the Hotel Margaret, on the corner of Columbia Heights and Orange Street. It’s hard to imagine the author of Kristin Lavransdatter in this neighborhood where, over the year, writers of a quite different orientation, from H.P. Lovecraft to Norman Mailer, have resided.

Undset gave lectures in the US, and Made influential friends (Willa Cather, Dorothy Day). She also undertook a secret project for first lady Eleanor Roosevelt—compiling a list of Norwegian libraries, historical buildings, and scientific repositories that needed to be protected in the event of occupation by the Allied forces.

After the war Undset returned to Lillehammer, where she had previously done her best literary work. But by the time of her death in 1949, Undset was already fading from the fickle memory of the literati. In a world of young beatniks and Cold War manias, her soul-shaking medievalist narratives simply didn’t fit.

That was hardly fair. Undset had been developing stream-of-consciousness techniques in her prose even before Joyce published Ulysses. And the medieval world in her writings is eerily contemporary in some ways, especially in Kristin Lavransdatter.

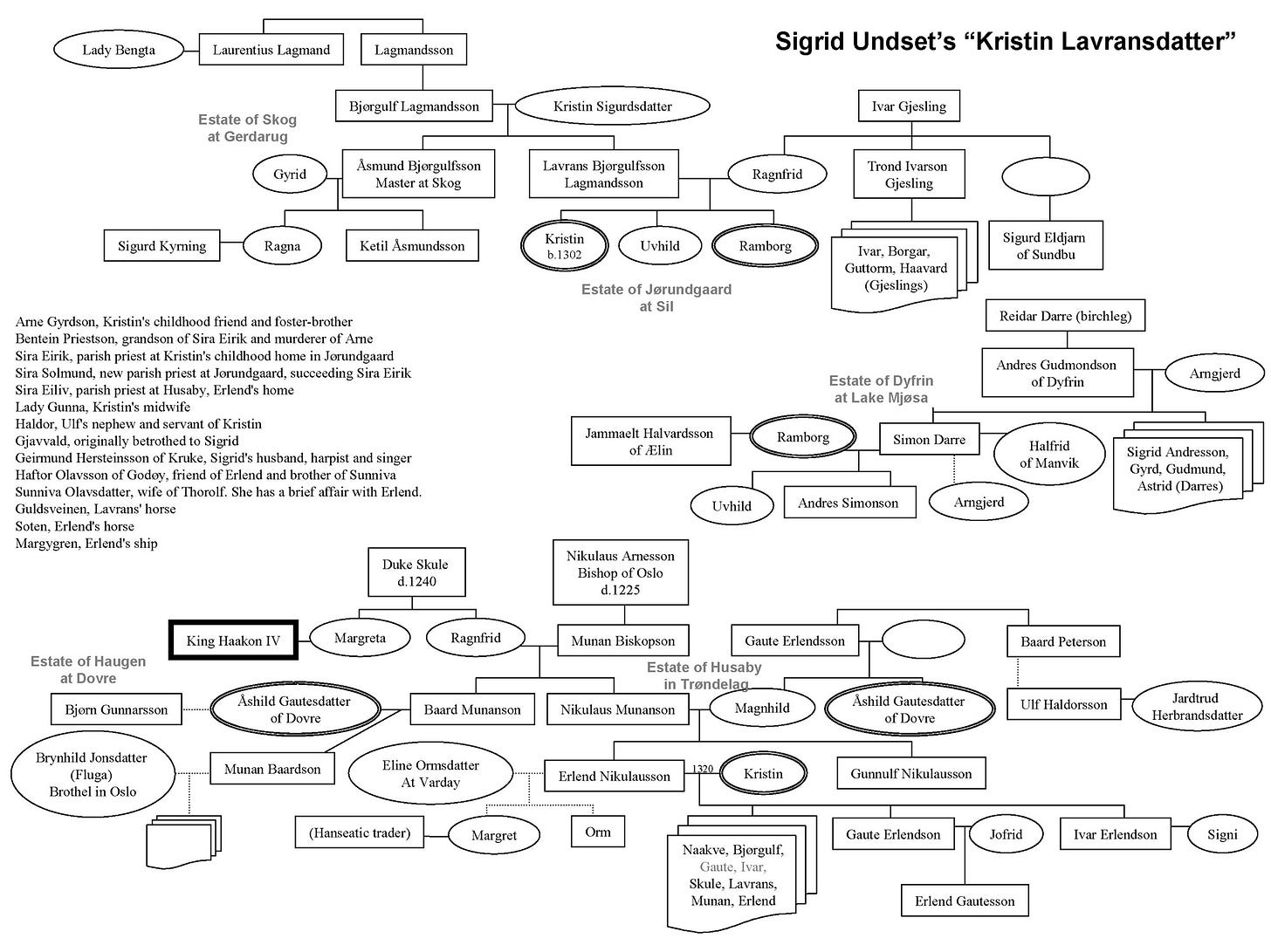

When I warned about the intricacy of the storyline, I wasn’t joking. Here’s a guide to the main characters of Kristin Lavransdatter.

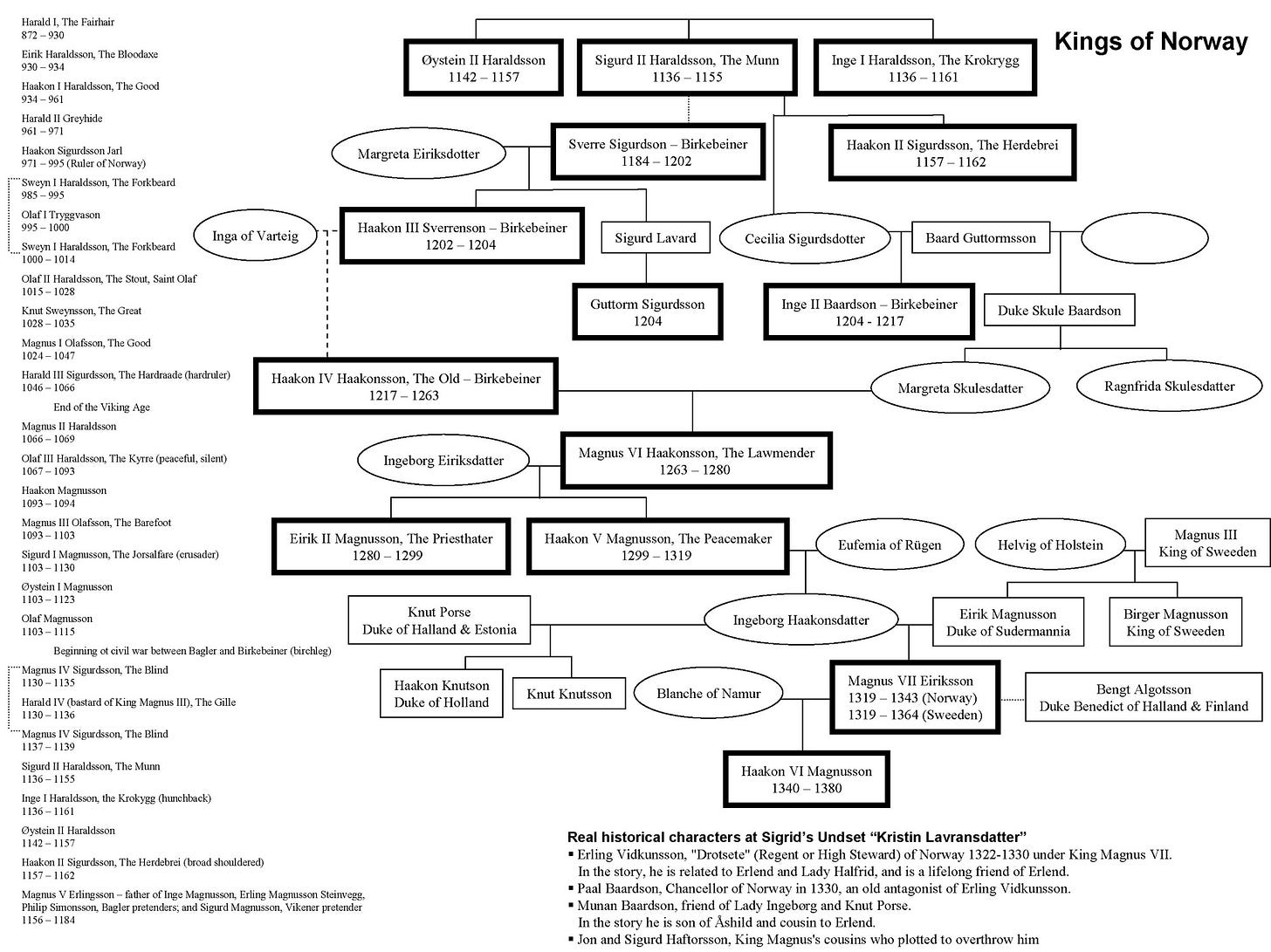

And because the story takes place in the 14th century, you really ought to know these historical figures too. Please don’t get your Haroldssons and Sigurdsons confused.

But don’t despair. Kristin Lavransdatter is really just a love story—but one of the most savagely honest love stories ever written.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Romance fiction may delight, but it rarely surprises us—after the first chapter, you can almost predict everything that’s going to happen. They will soon train AI how to churn out these stories. In fact, it may already be happening, judging by some recent offerings on the streaming platforms.

But nothing is more tired and predictable than the medieval romance. This type of story has been a literary dead end for hundreds of years—so much so that Cervantes was already mocking it when he wrote Don Quixote (1605), the ultimate send-off of the genre. And to be honest, the medieval romance had mostly exhausted its narrow range of devices a century before Cervantes made fun of its clichés.

We all know the formula. It requires a bold knight and a lovely, highborn lady, passionate love, and high adventure—with sword fights and secret rendezvous along the way. But the incidents are so predictable, and the emotions so stylized that whatever reality that might have set these stories in motion in the Middle Ages has long been lost to us. Instead we have stick figures, faux Lancelots and Guineveres, perhaps suitable for parody (along the lines of Monty Python and the Holy Grail) but lacking in any psychological depth or plausibility.

That’s where Sigrid Undset enters the picture, and shakes everything up. Not only did she return to the medieval romance in the twentieth century in this epic work, published between 1920 and 1922, but she somehow reverses a thousand years of morbidity, bringing a long dead genre back to life.

In honoring her achievement, the head of the Nobel Committee Per Hallstrom praised Undset’s way of presenting her characters “sympathetically but with merciless truthfulness”—not an easy combination for any author to achieve. Even more impressively, Undset conveyed the seemingly paradoxical notion that “the generations of the Middle Ages also enjoyed a more varied inner life than the present generation.” In other words, she not only overcame the stale narrowness of the medieval romance, but turned it into its exact opposite, a gripping inquiry into the full emotional turmoil of the human condition.

Perhaps the most stunning thing here is that Undset did all this without giving up the key ingredients of the genre. In Kristin Lavransdatter, we still have the bold knight and the highborn lovely lady, the passionate romance with flirtatious couplings, dangerous escapades, and swashbuckling sword fights. But in this novel, they are stripped of their fanciful and stylized aspects and invigorated with a degree of realism that’s almost painful to witness.

In some ways, this book is more like The Sopranos than Romeo and Juliet. The characters here will surprise and disappoint you by turns, inspire your admiration at one juncture, and repugnance at the next. Even when you love them, you still cringe. Perhaps that’s the essence of its appeal.

I might say that Undset turns medieval stick figures into real people, but that doesn’t do justice to her achievement here. You haven’t really encountered people like Kristin Lavransdatter in everyday life, or her ardent lover Erlend Nikulausson, or her rebuffed suitor Simon Darre. I’m tempted to call them hyperreal. They are as complicated and contradictory as the members of your own family, but in a turbocharged and amplified way. This heightening of lived experience is amplified by the deadly circumstances of their life and times, where dangers loom that hardly exist in the 21st century.

You and I are unlikely to get into an axe fight, or find ourselves in the king’s torture chamber, or excommunicated by cleric authorities, but in 14th century Norway these things were, if not everyday occurrences, actual penalties for people who made bad decisions. By displaying her powers of character description in these contexts, Undset created a powerful narrative that redefines our sense of the past and notions of superiority to long-dead predecessors and ancestors.

When we first encounter Kristin Lavransdatter, she is the young daughter of Lavrans Bjøgulfsøn, a devout and sober Norwegian nobleman, who is trying to find a suitable marriage partner for her. For those familiar with medieval romances, this is the expected starting-point, and the reader is not surprised when Kristin’s betrothal is announced to Simon Darre, son of a respected local landowner, or when a rival for her affections emerges, the dashing and headstrong Erlend Nikulausson. The romantic triangle is a tried-and-true device, and the driving force in countless plots from all eras and regions of the world.

But the way this triangle develops is quite unconventional. Our male romantic lead, Erlend, is no Mr. Darcy, and for every heroic quality he reveals, he also displays some disturbing character flaw. If this were a Hollywood script, the producer would send it back to the bullpen for rewrites. But this same unnerving character imbalance is just as salient in the two other participants in our love triangle.

Kristin is willing to sacrifice everything for her love, and you can’t help admiring this total commitment to her chosen partner—until her headstrong ways threaten to destroy everything else in her path. The loser in this game, Simon, would normally demonstrate his inadequacy, if this were a conventional romance, but instead he shows the most noble and heroic, if also self-destructive, traits of them all.

The end result is a book where you repeatedly wish you could enter into the story and advise the characters to reconsider their rash actions. But it wouldn’t make any difference. They are warned sufficiently by the other characters in the book, and to no avail.

But Sigrid Undset pulls off something remarkable here. Our compassion and respect for these flawed characters never abates, even as they disappoint us again and again. This runs against every rule of narrative structure, especially in romantic storytelling, where the reader is supposed to admire the lovers as idealized participants in a lovey-dovey fantasy world.

Undset’s work is often published and read in a single volume nowadays, but was originally released over the course of three years, in three separate volumes—Kransen (The Wreath) published in 1920, Husfrue (The Wife) from 1921, and Korset (The Cross) from 1922. While reading this book, I anticipated that the characters would rise above the self-imposed obstacles of the first volume—getting their act together, so to speak—and achieve something approaching triumph or resolution in the final chapters. That’s how plots usually develop. Complications emerge, but only to be resolved. Sigrid Undset, however, plays by different rules. Her story gets deeper, but at no point does it get simpler, nor do her characters abandon their paradoxical, but all too human, demeanor.

Undset’s intense spiritual worldview amplifies these expectations. Religion plays a large and recurring role in the plot, and we have some hope, or even expectation, that her main character will achieve a degree of saintliness. But few things are rarer than saints walking the earth—even in a spiritually-charged novel—and the tiny steps Kristin Lavransdatter makes toward a beautiful life, are almost always preceded or followed by stumbles, and occasionally complete reversals. Our hopes for her are never dashed, at least not completely, yet neither are they gratified by larger-than-life triumphs.

Yet we do well to remember that actual life, as we experience it, does not follow the narrative structure of a Netflix miniseries. And Undset’s seeming stubbornness in withholding expected cadences merely increases the verisimilitude of her finished work.

In fact, this novel is all the truer to its author’s worldview for its post-Edenic complexities. And perhaps all the more potent in its impact on readers, who may recognize themselves in its pages for the simple reason that Sigrid Undset does away with medieval figureheads and saintly lives. In this way, she somehow presents tales from the distant past that seem uncannily like the celebrity stories of our own time—but the resemblance is to the messy affairs from private lives (Kanye and Kim, Amber and Depp, etc.), and not the stylized formulas the stars present on screen.

Wow. Every summer I regularly visit a local park in Oslo, just 10 minutes walk from my apartment. This park has a very small restaurant and I have a special agreement they stock ouzo only for me. I love this place where I can stay for hours (if weather is OK) reading, listening to podcasts or meet friends. This park has a statue of Sigrid Undsæt and I often thought: When will I read some of her works? I’d never thought of the possibility an american (mainly) music writer would be the one who put me in action. I will visit my local second hand book shop. I’m sure this shop can supply with the trilogy and when summer arrives I will be in my local park, by the statue of Sigrid reading this history. It’s impossible not to do so after reading what Mr. Gioia wrote (and being a norwegian).

I read “Kristin” during the pandemic and was totally engrossed by it, for all the reasons you listed. Also, it was unsettling to read Undset’s very vivid description of the Black Death while COVID was raging across the globe. Pandemics will upend whatever plans humans have laid, then as now.