How Saxophonist Jimmy Giuffre Taught Me Organizational Theory

Or what I didn't learn about team-building at Stanford Business School

Years ago, I was writing a long chapter on saxophonist Jimmy Giuffre for my West Coast Jazz book, and I managed to track him down for an interview.

He was an unusual man with peculiar opinions, to say the least. Then again, that might be why he was such a creative jazz musician. In any event, I go into such situations prepared for anything.

Giuffre was 36 years older than me—so I obviously had to deal with a generational gap. But as our conversation proceeded, I realized that this was just the start of our differences. As he spoke about his guru (Wesley La Violette) and theories of life, I wondered whether I was talking to a musician or a mystic.

Put simply, Jimmy Giuffre did things by his own rules. But sometimes they were so odd, they didn’t even look like rules.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

For my research, I tracked down all his albums—not easy because, even back then, most were out-of-print. And the more I listened, the less I understood Jimmy Giuffre. Because each record was different, often dramatically different.

I couldn’t even begin to figure out his approach to bandleading. The instrumentation, for a start, made no sense to me.

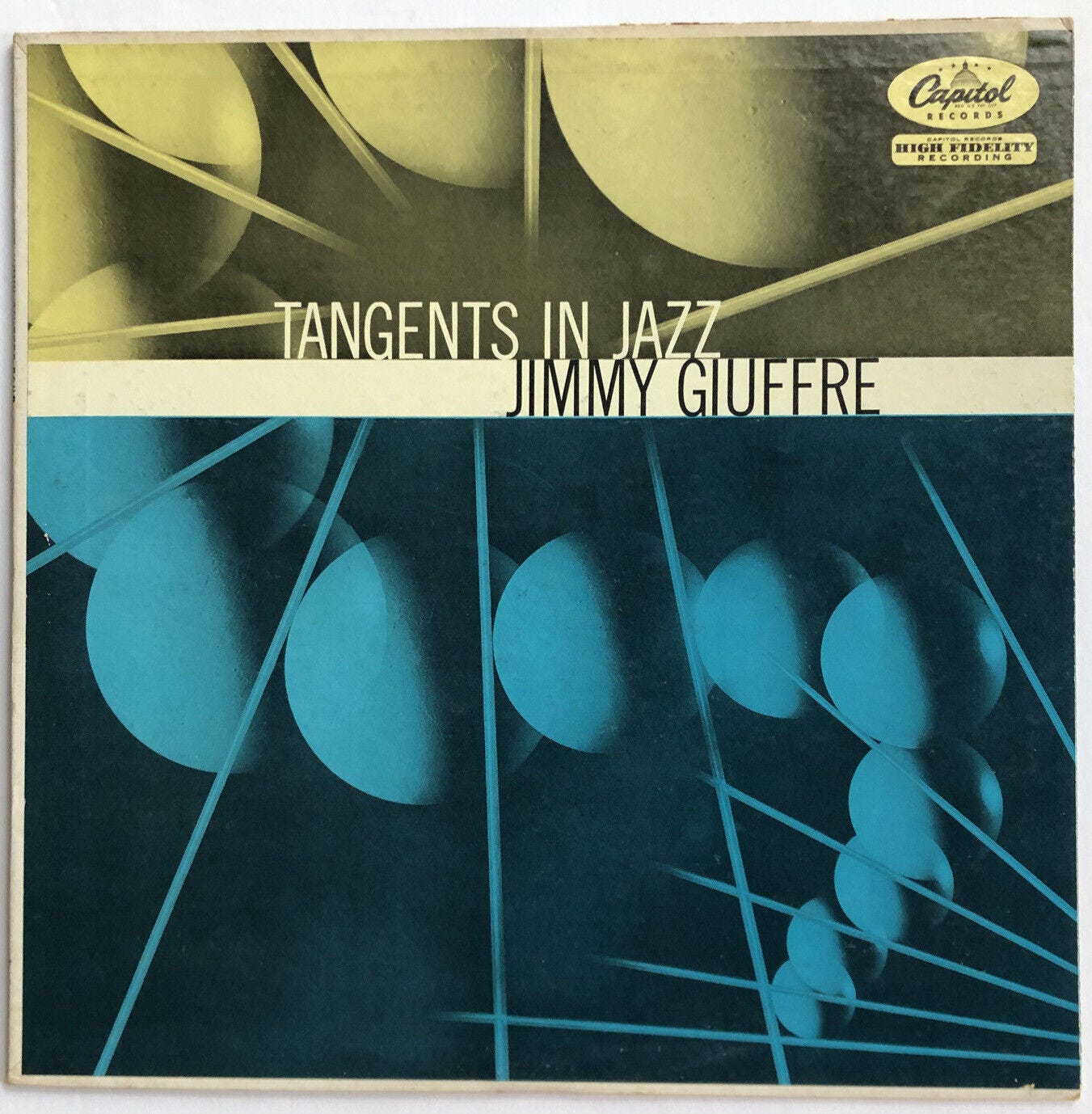

Let’s start with Tangents in Jazz, recorded in 1955, where the quartet has no chord-playing instruments—relying just on sax, trumpet, bass, and drums. Maybe, I thought, he was imitating the famous Gerry Mulligan pianoless quartet, which sold a lot of records with a similar lineup. But the next album, The Jimmy Giuffre Clarinet, found him abandoning sax for clarinet—as well as bass clarinet, alto flute, bassoon, English horn, celeste, and a bunch of other instruments you don’t bring to a jam session.

Music fans in the 1950s had no compass for dealing with music of this sort—which hardly sounded like jazz.

All this seemed risky to me, almost snubbing one’s nose at the jazz community. A musician would pay a heavy price for releasing album after album filled with sound palettes that few jazz radio stations would dare play.

But by the time of Trav’lin Light (1958), the instrumentation was far more radical, in fact unprecedented. Had any musician in any genre ever recorded (or even performed) in a trio consisting of clarinet, valve trombone, and guitar?

And Giuffre brought that same band to Newport for his celebrated appearance at the 1958 jazz festival. Once again, fans must have been shocked by a 1950s jazz combo with such unidiomatic sounds—with no piano or bass or drums (the key ingredients to most jazz rhythm sections) to set the beat and propel the groove.

By the way, it sounds great.

Follow-up projects found him playing alongside bass and guitar. Or piano and bass. Or bass and drums. Or just flying solo as on much of his 1962 recording Free Fall.

There seemed no rhyme or reason to such choices—which were always unexpected and never lasted long. So I was determined to get to the bottom of this. How did Giuffre make decisions on group formation?

When other interviewers pressed Giuffre on these kinds of subjects, he would take the topic and run off in almost any direction. In one article I read, he actually critiqued Ford Motor’s assembly line processes—not something I expected to hear from a saxophonist—and made unconventional comments on organizational structure.

This was, by chance, a subject I’d studied in business school under one of the best experts in the field. And I’d also put this learning into practice at McKinsey, where I’d worked right before leaving to write my jazz book.

I thought I knew a little bit about organization theory.

So when Giuffre finally agreed to talk to me, I decided to press him on this specific subject. For a start, I reeled off a list of all the odd combinations of instruments from his albums, and pressed him for an explanation.

His response shocked me. He didn’t really pay attention to the instrumentation, he claimed.

That can’t be true, I replied. Nobody in jazz makes more daring choices on band line-ups. There had to be a logic behind this.

Giuffre hemmed and hawed. And then he admitted that he picked musicians based on how well everybody got along. The instruments they played weren’t especially important.

That couldn’t be true. Or could it?

I had always assumed that you started by identifying the instruments you wanted in the band—which was pretty easy in jazz, because the formats were fairly standard. And then you hired the best musicians you could afford, based on how much the gig paid.

That was how I did it. That was how everybody did it.

Back when I interviewed Jimmy Giuffre, I was gigging constantly and the format was obvious. The best option was piano, bass, and drum with at least one horn. If I didn’t have enough money to cover that, I brought just a trio—piano, bass, and drums—to the gig. If I couldn’t afford that, I did just piano and bass. And if cash was really tight, I opted for solo piano.

And which players did I hire?

Back then, I wanted play with the best of the best. I kept careful tabs on all the jazz musicians in the greater San Francisco area, and my goal was to perform with the top cats. Even if I didn’t know the musician, I’d make a cold call and try to hire them, provided I could afford it. If I got turned down, I went to the next name on my list.

Didn’t everybody do it that way?

Not Jimmy Giuffre. He explained that musicians played better when they were happier. Now that was a word I’d never heard in organizational theory class.

Giuffre continued to spell it out for me—surprised that I couldn’t figure this out for myself. Didn’t I know that people are always happier when they were with their friends? So group productivity is an easy problem to solve.

In other words, if my three best buddies played bongos, kazoo, and bagpipe, that should be my group.

When I heard this, I thought it made no kind of sense. They don’t call it ‘show friends’—they call it show business. I couldn’t imagine following Giuffre’s advice.

But over the years, I’ve thought a lot about what Jimmy Giuffre said about group formation—which is not only unusual for a music group but also violates everything I was taught back at Stanford Business School.

I now think he was on to something. So I wasn’t surprised when I recently ran across an interview with pianist Paul Bley (conducted by Ted Panken), who said something similar:

“The trio format is flawed. If you’re going to put three musicians, it should be because they’re three musicians, and the fact that one plays the trombone and the other plays whatever is not the point. You’re hiring individuals. Any format is already dead.”

I note that Giuffre hired Paul Bley for his band back in 1961, when the pianist was still little known. I often wondered why Giuffre, who had worked without piano for many years, suddenly changed his mind around the time of his fortieth birthday. I don’t wonder anymore—I just assume that Jimmy and Paul hit it off together.

But even more persuasive to me is my retrospective consideration of my own performing career. I’ve tried to identify those times when I felt everything clicked, and the music reached some higher level of immediacy and expressivity. And guess what? I have to admit that, in my own life, the best music came in settings where I was working alongside people who were friends.

I doubt that Giuffre knew about John Ruskin’s quirky views on individualism from “The Nature of Gothic” (although with Giuffre, anything was possible). Ruskin was a must-read author 150 years ago, but not so much nowadays. But he had a jazzy sensibility—as much as that was possible in Victorian England.

Ruskin argued that the glory of medieval architecture depended on artisans refusing to take orders, and imposing their own eccentricities on the work at hand. So we end up with gargoyles and rule-breaking curlicues instead of streamlined buildings.

These words, written by Ruskin in the 1850s, have been very important to me over the years. But the funny thing is that I understood their implications for the arts long before I realized how they also applied to other things:

Imperfection is, in some sort essential, to all that we know of life.....Accept this then for a universal law, that neither architecture nor any other noble work of man can be good unless it be imperfect….The first cause of the fall of the arts of Europe was a relentless requirement of perfection…..

Now, in the make and nature of every man, however rude or simple, whom we employ in manual labor, there are some powers for better things….In most cases it is all our own fault that they are tardy or torpid. But they cannot be strengthened, unless we are content to take them in their feebleness, and unless we prize and honor them in their imperfection above the best and most perfect manual skill.

Giuffre had a comparable view, except that he wanted to do this in the 20th century, and as part of a progressive jazz environment.

Can I turn this into a rule? And, even more to the point, could you apply this to other settings? Could you start a business with this approach?

That seems like a recipe for disaster, at least at first glance.

But I now think even large corporations could benefit from a dose of Jimmy Giuffre’s thinking. One of the biggest mistakes in hiring practices, as handled by HR (Human Resources) professionals in the current day is an obsession with the “required qualifications” for the job. They won’t even give you an interview unless you mention the right buzz words on your resume. But the best people take unconventional paths, and this checklist approach will exclude precisely those individuals.

(I’ve even heard of a scam for getting interviews—which involves copying and pasting the job description word-for-word at the bottom of your resume. This apparently rings all the bells in their algorithms and gets you moved to the top of the candidate list.)

Giuffre’s quirky theory gets straight to the heart of the problems with contemporary society outlined by Iain McGilchrist in his book The Master and His Emissary. That book is ostensibly a study of neuroscience, but is actually a deep-thinking critique of institutions and cultural biases. The best decisions. McGhilcrhist shows, are made by holistic thinkers who can see the big picture, but the system rewards the detail orientation of people who manage with checklists and jump through all the bureaucratic hoops.

Yet I’ve seen—and I’m sure you have too—amazing people whose skill set can’t be conveyed by their resume. Not even close. I’ve worked alongside visionaries whose education ended with high school, but have ten times the insight and ability as their colleagues with graduate degrees and fancy credentials.

That’s why Duke Ellington is such a great role model for running an organization. He hired people because of their musical character, rather than their sheer virtuosity or technical knowledge. And he certainly paid no attention to formal degrees. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Duke went through decades of hiring for his band without looking at a single resume.

That piece of paper wouldn’t have told him a single thing he needed to know.

For all those reasons, I no longer dismiss Jimmy Giuffre’s peculiar views on group formation. I’d recommend them myself—maybe even especially in groups where no music is made.

Ted: "Yet I’ve seen—and I’m sure you have too—amazing people whose skill set can’t be conveyed by their resume."

Case in point: my father. Never finished College, but became an official in the state HIghway Department. Then, the state decided that non-degreed engineers could achieve the same status as College grads by passing a rigorous exam. Somehow, Dad didn't qualify for this exam! But who did they ask to create this exam?

Yup. None other.

This was a very thought-provoking piece. As a Project Manager working in the business world for my entire career, I actually feel Giuffre's philosophy has been confirmed by Harvard Business Review and other corporate influencers I've read who argue that building a team that feels safe, supported, and trusted and embodying principles of "servant leadership" yields the objectively best results in most cases.

In other words, if leaders pick the right people, stay out of their way, and offer them the support they need to work through problems, they will see better outcomes than the traditional methods of top-down control and planning, which simply aren't adaptive enough to keep pace with a much more highly complex, interdependent, and fast changing world than people were living in back at the time of Henri Fayol and other early theoreticians of management .

It was very interesting to read how this had been applied in jazz - the most democratic of musics - decades before the theoreticians and bean-counters had caught up!