How Nobel Candidate Javier Marías Became King of a Caribbean Island Because of a Novel

There are many strange things about author Javier Marías, but the strangest is his accession to the disputed throne of the Kingdom of Redonda

There are so many bizarre ingredients to this story, I don’t even know where to begin—except with a disclaimer. Everything here is true, even the parts that seem the least likely. In this instance, truth is not only stranger than fiction, but fiction made the truth even stranger.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The Nobel Lit Prize Candidate Who Would Be King

by Ted Gioia

Part I: What Is This Famous Novelist Hiding?

Javier Marías, the Spanish novelist who recently celebrated his 70th birthday, is one of my favorite living authors. Yet he’s still a bit of a mystery to me—even after having read almost everything by him I can get my hands on.

In fact, the more I learn about Marías, the stranger he seems. It’s hard to read his books without imagining him keeping deep and dark secrets. Perhaps even living a double life under an assumed name or names.

That may seem unlikely, or even impossible, for such a well-known international figure. After all Marías is frequently mentioned as one of the leading candidates for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He may be the most prominent living novelist writing in Spanish—which, perhaps to your surprise, has more native speakers around the world than even English.

How can someone so visible have a secret life?

Marías is himself to blame. His novels keep returning to the same story again and again. They almost always deal with a prominent intellectual—usually an academic, or writer, or translator—who has an undercover job, usually as a spy or intelligence agent. Even the people closest to these characters are kept in ignorance of what their work actually involves—and the glimpses that we, the readers, get of this subterranean existence are filled with dubious ethical choices, blatant lies and deceptions, even violence and murder.

“I sometimes feel you that you must be careful about what you make up and write down in books,” Marías confesses, “because occasionally it comes true.”

Based on my description, you might think that Marías is the author of spy novels, a kind of Spanish Ian Fleming or John le Carré. And that wouldn’t be entirely wrong—Fleming, the creator of James Bond, actually figures in the plot of Your Face Tomorrow, the remarkable trilogy that is Marías’s most impressive achievement. But I don’t want you to be misled. My favorite Spanish author is closer in spirit to Marcel Proust or Henry James than to any genre writer. His heroes are scholars and intellectuals first, and only spies by accident.

But even the intellectual aspects of these books tell us of hidden lives. Marías quotes Shakespeare frequently (not a typical practice for a Spanish novelist), but always from plays and scenes where characters fear those around them are living a double life, or are hiding their own secret activities. The title from A Heart So White is drawn from Lady Macbeth’s private admission of her bloody guilt. The title of Your Face Tomorrow, taken from Henry IV, Part 2, is interpreted by the author as an expression of the uncertainty of knowing the real truth about our closest friends or even about our own future selves. Marías especially likes to quote from Othello, that ultimate source of psychological speculation about the hidden activities of our nearest and dearest.

What is this author hiding?

Adding to my suspicions, many of the novels draw their stories from Marías’s own life—indeed, the protagonists resemble the author to an uncanny extent. Marías has even written an entire book about the problems he’s created for himself by using his own experiences as building blocks for his stories. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that Javier Marías has glimpsed the dark side. Or perhaps more than glimpsed it. Maybe he’s even operated in its shadow, or its innermost sanctum.

In one of his works, Marías quotes the penultimate letter from his mother, who was also capable of keeping secrets—so much so, that he was unaware of her final illness until literally the last moment, only learning about it immediately before her death. In this eerie letter, she recalls how she was alarmed at her son’s sadness when she had last seen him, and speculated that he perhaps had some hidden reasons for it:

“The capacity for respect that leads me to forget the secrets people tell me, for I never reveal them and I try to make peace, has been useful to other people more than once … and to you boys? Can’t I help you?. . . . I know that there is something I don’t know, and that always makes me give free rein to my imagination when it has to do with you boys. . . . There are so many problems around all of you!”

Something is lurking beneath the surface here, no?

All that is just idle speculation on my part. Yet one aspect of Marías that is a matter of public record is as strange as anything you will encounter in contemporary fiction. Through a peculiar sequence of events, he became the ruling monarch of the kingdom of Redonda.

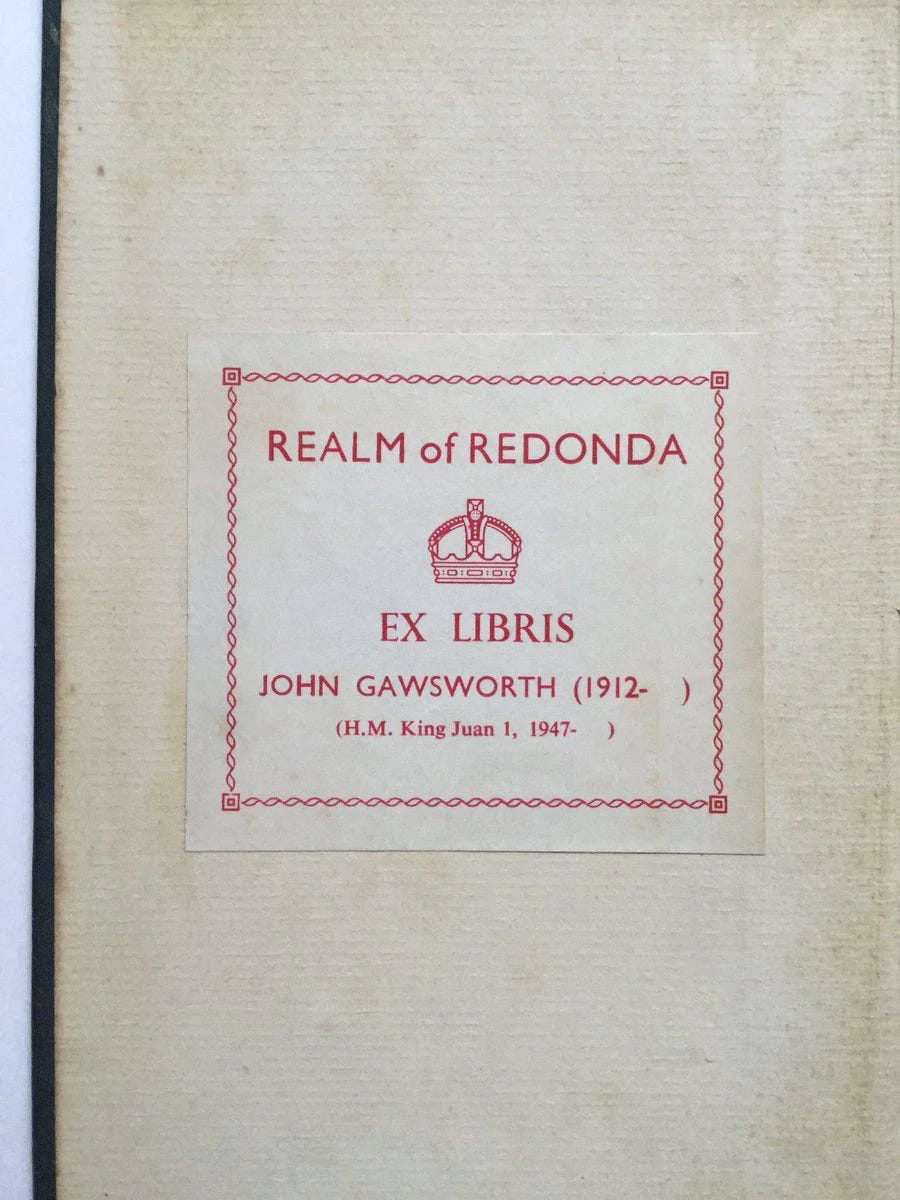

This is one of the most peculiar instances you will ever find of real life imitating art. Marías would have never ascended to the throne if it wasn’t for his obsession with shady, secretive characters, and one of the most interesting of them all is an almost forgotten writer named John Gawsworth (1912-1970).

You will need to pay attention to the details of Gawsworth’s odd life to understand the story I’m telling. But that’s an engaging task, and it will be worth your while to learn about this individual. Gawsworth may not have been an especially skilled writer, but his life is the stuff of movies.

Part II: Who is John Gawsworth, and What Was His Secret?

To start with, Gawsworth was not his real name—he was born as Terence Ian Fytton Armstrong, probably in West London. He claimed he was a descendant of the ‘Dark Lady’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets, but at other times he would brag of his relationship to Ben Jonson or John Milton’s wife. But it was hard to figure out who he really was.

Gawsworth wanted it that way. He used a confusing number of other names over the years. That’s perhaps an accepted practice for authors, where these aliases take on the respected title of pseudonyms. But Gawsworth pushed this embrace of secret identities to an extreme. If you find his published works—not an easy task, I warn you—they might be attributed to Orpheus Scrannel or Fytton Armstrong or some other identity. And the locations where he published his works are even more peculiar: Tunis, Calcutta, Vasto on the Adriatic coast of Italy, Setíf in Algieria, Cairo, and other locales.

Why was Gawsworth in these places? How in the world did he manage to publish his writings there? What were his reasons for all the traveling and name changes? And, above all, why was Javier Marías, Nobel candidate, interested in this individual—who, by his own admission, was a mediocre author with limited literary talent?

Marías never adequately explains his obsession, but readers of his books can easily answer it. The key characters in his books travel for their secret career as a spy or espionage agent, and their surface activities as a writer serve as a perfect excuse. After all, writers don’t need to check in at the office, and can show up almost anywhere—parties, embassies, sleazy bars, backroom poker games—without anyone being surprised in the least. Was John Gawsworth one of these double agents?

There’s always a giveaway clue in these cases. In almost every instance, the writer or intellectual or academic in question served some time in the military—which is part of their public record—and usually in intelligence or on-the-ground in some trouble spot. I’ve heard people hint that beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who recently passed away at age 101, was actually a spy. That’s a far-fetched notion—but their best evidence is his position as a Lieutenant Commander in the Navy, handling responsibilities in some dangerous settings before becoming a beatnik. But in this instance Gawsworth fits the bill perfectly. Of the few surviving photographs of the author, one shows him in a Royal Air Force uniform, and looking every bit like a military man, even wearing a medal.

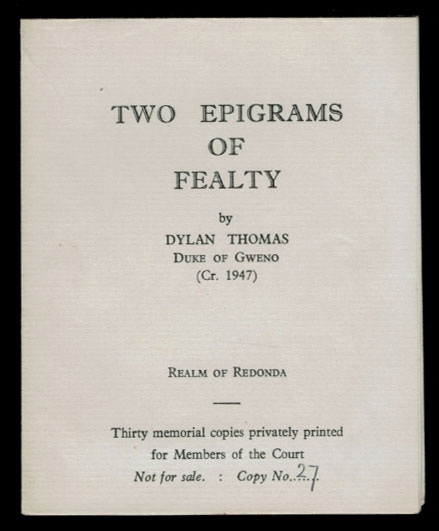

But if Gawsworth’s military responsibilities are vague, his cultural connections are almost ridiculously impressive—especially for a figure destined to be forgotten by the literary world. In his day, he was the youngest member of the Royal Society of Literature, an elite group which even today has only 600 members. He counted some of the most famous writers of the century among his friends, including Dylan Thomas, Lawrence Durrell, and Henry Miller—each of whom he later honored by making them dukes of the Kingdom of Redonda. He met William Butler Yeats and Thomas Hardy late in the their lives, and also hung out with a range of other intellectual celebrities from Rebecca West to Havelock Ellis. And the renowned authors he hadn’t met still found a place in his life, because he owned Charles Dickens’s skull cap, a pen once used by William Thackeray, and other items that we would nowadays call memorabilia.

But even more to his credit, Gawsworth made a point of helping out writers who needed assistance. He would pester the Royal Society, insisting that they provide financial assistance to these writers. His efforts on behalf of Arthur Machen and M.P. Shiel are especially noteworthy, because these writers had served as his own mentors and now he was trying to return the favor.

Part III: How Did John Gawsworth Become a Beggar and King at the Same Time?

The connection with Shiel led to Gawsworth taking on his most unusual pseudonym of all as King of Redonda. Gawsworth was fiercely loyal to this old friend, even keeping his ashes in a biscuit tin—and allegedly using a pinch of them as a condiment when dining with a honored guest.

As executor to M.P. Shiel, he inherited not just a tin of ashes and some literary rights of meager value, but more importantly, the throne of Redonda—little more than a big rock in the Antilles, but with a documented history dating back to Christopher Columbus who gave the island its name in 1493, when it was dubbed Santa María la Redonda. Shiel had received Redonda from his father Matthew Shiel, the son of a slave who had mixed Caribbean and Irish ancestry, and had claimed title to the island in 1865.

In fact, his dad had crowned himself as King Matthew I and declared the small island’s independence of all foreign powers. It’s not clear how many inhabitants there were then, if any—the rock is mostly a roosting place for sea-birds, whose guano and some aluminum phosphate are the only natural resources of value. The island’s independence has not gone unchallenged. Sovereignty is currently claimed by Antigua and Barbuda, and by Britain in the past. But the history is murky, and the relative lack of interest of other nation states made it possible for the monarchy to persist, albeit in exile.

When Shiel died, his kingship passed on to his executor Gawsworth. And few monarchs have made more use of such a tiny domain. He enthusiastically added another new identity to his list of pseudonyms: His Majesty King Juan I. And he began naming dukes and admirals, drawn from his friends, many of them famous. It’s an impressive aristocracy, whose ranks included J.B. Priestly, Vincent Price, Dylan Thomas, Ellery Queen (a pseudonym in its own right), Dorothy Sayers, Lawrence Durrell, and Dirk Bogarde. Dylan Thomas even wrote “epigrams of fealty” in response to the honor.

Gawsworth himself would soon need charitable handouts. His alcoholism punished him both physically and financially, leading to his dismissal from the Royal Society, and later to eviction from his home. He was a street person, and without a permanent mailing address he couldn’t receive his pension or government assistance.

Lawrence Durrell recalls his last encounter with Gawsworth sometime around 1956, when he encountered the King of Redonda by chance on the streets of London in a beggarly condition but pushing an enormous baby carriage.

How strange to see this familiar figure with young children, thought Durrell—in fact, there would be room for twins or perhaps even triplets in that massive pram. But a peek inside showed that there were no children enclosed, merely a huge stash of empty beer bottles that he was returning for their deposits, obviously planning to use the money to replenish his stock of spirits. This was 14 years before Gawsworth’s death, but by all indications his literary career was already over. When he died in 1970, Gawsworth was a forgotten figure from a distant past, whose passing went by all but unnoticed

Part IV. How Did Javier Marías Ascend to the Throne of Redonda?

This obscurity was so extreme that when Javier Marías shared Gawsworth’s story some twenty years later in his book Todas las Almas (translated into English as All Souls in 1992), many readers believed he had made up the entire mad tale of the King of Redonda who hobnobs with the rich and famous and ends up a beggar on the streets of London.

But the story was scrupulously accurate and honest. Marías had long been obsessed with this figure, having written about him even earlier in a newspaper article from 1985, and addressing Gawsworth again in his nonfiction book Negra Espalda del Tiempo in 1998.

At this juncture, it’s hard to separate truth from fiction—then again, that’s always the cussed problem with novelists, and few more cussedly than with Marías. If I can judge correctly from the novel All Souls, Marías’s passion for Gawsworth began as a kind of macabre book collecting challenge—the dead man’s works were devilishly difficult to find. But his quest was no doubt amplified by the curious details of the rise and fall of the King of Redonda. And, as many collectors know from their firsthand experience, it’s easy to get obsessed with the stories behind the collectibles too. Marías tried to piece together the scattered facts of Gawsworth’s life and times, a process that proved just as challenging as getting his hands on those rare books.

At a certain point in the collecting process—and I’ve seen this firsthand with the great blues collectors of the 20th century, and even in my own life—you begin to take on a larger responsibility for the people whose work you collect. You defend their reputations. You work to get their books or records back into print. In some instances, you even track them down, often now old and decrepit, and try to restart their careers. (That was the whole final phase of blues collecting mania of the 1960s, and perhaps the most fascinating chapter of them all.)

In Gawsworth’s case, there would be no encores of this sort. He might easily have lived long enough to meet his champion Javier Marías, but that wasn’t his destiny. But Gawsworth did make one last attempt at creating a legacy in the final days of his life. Broken down and near death, he told his friend Jon Wynne-Tyson (1924-2020), an author and environmentalist, that he was making him not only his literary executor, but was also bequeathing him the Kingdom of Redonda. At Gawsworth’s death in 1970, Wynne-Tyson became King Juan II.

But all kings must plan for their posterity, and Wynne-Tyson, who died a few months ago, also needed an heir to hold the tiny (or perhaps non-existent) throne. And who was more deserving, or a more loyal subject, than the famous Spanish novelist who had done so much to celebrate the Kingdom of Redonda and its literary monarchs?

Accordingly, he passed on the title to Javier Marías. If Marías hadn’t led a double life with a second job before, he certainly had one now. And like Gawsworth before him, Marías has made full use of his disputed claim to this minuscule piece of land, less than one square mile of uninhabited rocky terrain in the West Indies. He assumed the title of King Xavier. He has handed out titles. He has preserved history—even acquiring, I’m told (but who knows what to believe in those whole twisted tale?), the “Royal Archives” of Redonda—namely ten boxes of Gawsworth’s private papers.

“I sometimes feel you that you must be careful about what you make up and write down in books,” Marías confesses, “because occasionally it comes true.”

But to Marías’s credit, he has paid the best possible homage to the past by setting up the Kingdom of Redonda publishing imprint, which he uses to preserve the works of those forgotten authors from the past, even those who had less than a tiny piece of rock and a disputed title to their name.

What a wonderful tale! Thank you for introducing us to such fascinating people!

https://www.sommollet.cat/noticia/92924/un-llibre-del-viatge-de-javier-dieguez-al-regne-de-redonda