How Musicians Were the First Heroes—And Their Songs a Kind of Superpower

In this section from my new book, I explore the secret origins of musicology as a guide for dangerous journeys

Below I share a section from my new book Music to Raise the Dead.

Each part of the book can be read on its own. But if you want to check out the rest of it, click here for an overview and links to the chapters I’ve already published.

For the time being, this work is only available online via my Substack.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Where Did Musicology Come From? (Part 2 of 2)

By Ted Gioia

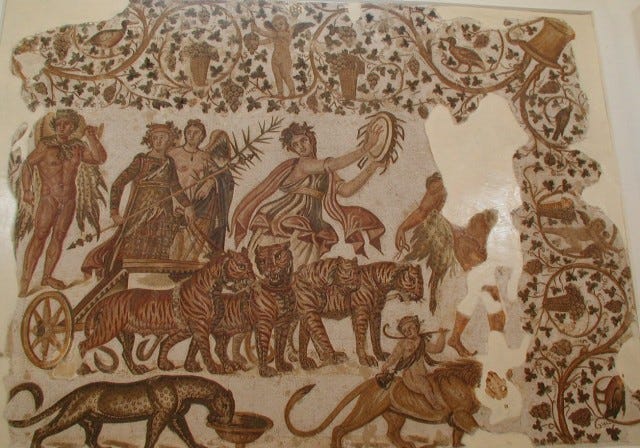

Magical, musical chariots are everywhere in the early history of religion.

These vehicles are constantly invading the air space of people down below—and descriptions frequently focus on the sound they make. In Hindu texts, they are called Vimanas, which translates as chariots, but some commentators prefer to describe them as aircraft. After all, they make lot of noise and fly in the air, so why not?

This conveyance is described in the Mahābhārata as “divine, brilliant as the morning sun, filling the horizon with its roar.” Elsewhere we are told that when “demons hear the sound of the chariot, they arm themselves and close the gates of the city.”

In another passage, we encounter a fierce battle scene described as a kind of rhythmic performance. The chariot wheels are part of the music:

“Then the beat of drums and tabors, the din of chariot-wheels and of kettledrums, and the fierce lion-roars of the heroes erupted throughout the Kuru forces. Arjuna’s bow Gandiva sounded like thunder; the sound reached the heavens and the horizon.”

Some of the surviving ancient passages are puzzling, such as the Edicts of Ashoka from the third century BC. This inscription on stone describes how “the sound of the drums becomes the sound of morality, showing the people the representations of aerial chariots.” Scholars continue to debate the meaning of this passage, but it clearly refers to the rhythmic or sonic aspect of a magical journey.

Here, again, we are reminded of the shaman’s drum—which also is considered a mode of transportation. The shaman rides it as if it’s a horse. And its rhythmic power propels a similar kind of magical mystery tour.

Of course, the most famous flying chariot in Western culture comes from the ancient Greeks. In their mythic worldview, Apollo drove the radiant chariot of the sun each day—bringing light to the world. I note that Apollo is also the god of music, and that he is often depicted holding a lyre.

We will encounter magical and musical chariots again in the next chapter. There we try to understand a fantastic journey described in the fragments of Parmenides, who is sometimes considered the founder of metaphysics and ontology in Western philosophy. But his sole surviving work is (as we shall see) a song about a mystical trip by chariot.

The curious thing here is that Parmenides and the other Greek pre-Socratics are not considered religious or mystical figures, but rather as the inventors of secular and scientific thinking. Yet even there, at the origin of our own logical conceptual framework—literally the birth of Western rational thought—we encounter the rhythmic propulsion of a flying chariot.

What in the world—or out of the world as the case may be—is going on here?

In fact, these aerial conveyances are so common in various ancient traditions that many UFO conspiracy theorists are convinced they represent spaceships from extraterrestrials. That theory was outlined most famously by Erich von Däniken, who sold some 70 million books about these so-called Chariots of the Gods, the title of his most famous work. According to that hypothesis, any music made by these vehicles must be truly otherworldly.

But based on the research we’ve already seen in the preceding chapters, no visitors from outer space are required to explain these old narratives. They describe journeys of personal transformation, not interstellar trips, and the persistent descriptions of rhythm make clear that we are dealing with a trance experience aided by music. We described the scientific and biological basis for these journeys back in chapter three.

The sources of this in the Judeo-Christian tradition go back to the prophet Ezekiel. This is a key scripture celebrated in songs, images, and textual commentary—yet interpretations of it have been shrouded in secrecy. Saint Jerome, in a letter, relates that the opening passages of the Book of Ezekiel involve “so great an obscurity” that they “are not studied by Hebrews until they are thirty years old.”

That might be an understatement. Various Jewish sources indicate that even mature age was insufficient to approach this sacred text. Gershom Scholem, the leading modern guide to the subject, discusses “conditions of admission into the circle of Merkabah mystics” which involve (much like the Native American quests discussed previously) both “moral requisites of initiation” as well as “physical criteria” before you were allowed to study the magical, musical chariot.

And what exactly is described by the prophet Ezekiel?

The passage relates a vision of a chariot in the sky, transporting four creatures. The whole account is less than a thousand words, but it focuses with intensity on the wheels of the chariot and their sound, “like the noise of great waters, as the voice of the Almighty, the voice of speech, as the noise of a host.”

It’s worth noting, in this regard, that the first studies of entrainment—when brainwaves match external rhythms, creating a sense of euphoria—were based on observing people hypnotized by rotating wheels. In the case of Ptolemy, the first to study this effect, the spinning wheels allowed flickering glimpses of a light behind them, shining through the spokes. This created a rhythmic visual pattern that proved trance-inducing. In other words, both the appearance of the chariot wheels and their sound serve as evidence that the prophet’s vision was what we would nowadays call an altered mindstate, instigated at least in part by rhythm.

The Merkabah mystic aspired to similar ecstatic experiences of the divine as already described elsewhere in this book—in accounts of Orphic practices, shamanic rituals, vision quests, etc. Yet scholars have been immensely frustrated by the surviving descriptions of these mystical Merkabah journeys, which seem almost deliberately nonsensical.

Many of these old documents and fragments are filled with precise measurements, as if the authors were trying to be as clear and specific as possible. But Scholem is forced to admit that “the enormous figures have no intelligible meaning.” The scenes described, despite their superficial precision, are “impossible really to visualize” and “reduce every attempt at such a vision to absurdity.”

In a strange sort of way, all these bizarre attempts at quantification remind us of musicology in the present day. The idea that you can take something as magical as music and reduce it to numerical relationships, seems a misguided or even impossible mission, at least at first blush. But that is exactly how music is now studied, codified, and taught.

Even the prevalence of the term digital music, which once might have seemed a joke or oxymoron, indicates how readily we embrace numerical systems as substitutes for the essence of the songs we sing. We do well to remember, however, that the moment we start singing, the digital realm is left far behind. When those first notes escape from our lips, we have entered a more powerful—and unpredictable—experiential realm.

But long before MP3 files existed, musicologists aimed to do something similar. They took something as intangible as a song, which seems more an emotional force than a mathematical truth, and reduced it to numerical relationships. In a way, I find it charming that the Merkabah mystics aspired to something similar, only in their case the numbers never really added up. They couldn’t—because what the mystics experienced firsthand rejected such narrow constraints.

So I will spare you the enumeration of gates, seals, angels, and secret names that these mystics have left us. They simply reinforce the message that the map is not the territory, and that no verbal description captures the ecstatic, life-changing experience of the journey itself. We find the exact same thing in other written texts from other visionary traditions. They try to convey in clumsy representations something that no words or data stream can adequately encompass.

This is why music plays such a significant role in all of these mystical practices. Songs tap into a power that transcends representation. But you already knew that from your firsthand experiences as a listener. For many individuals, music is their only pathway into ecstatic mindstates. And even for the adept who has mastered the journey, the song is often the most important thing brought back from the trip—or, in many cases, music served as the engine that propelled it forward in the first place.

We find this too in Merkabah narratives, where the visionary cannot hope to bring back the chariot or throne, but can return with a song. So we shouldn’t be surprised that the Maaseh Merkabah, one of the most important documents of this tradition, is a collection of hymns. These are not devotional songs in the typical sense, but were actually heard by travelers into the world beyond during their trip, and retained on the return journey.

Here again, the music eludes verbal description—but not for lack of trying. Consider this passage from the Pirkei Hekhalot, which tries to convey what it’s like to hear music associated with the chariot:

“He seats you in a wagon of radiance and he blows the equivalent of eight thousand myriad horns, three thousand myriad shofarot, and four thousand myriad trumpets.”

That’s some rockin’ band—bigger than any earthly orchestra in human history. But the description can’t be taken literally, can it?

As with so much of this literature, the details are offered not to inform or define. Instead they alert you that no amount of data will ever capture the actual experience of the visionary. So don’t expect to download this soundtrack on a MP3 file.

We can hardly imagine the actual music, let alone recreate it. True, some lyrics have been preserved, but they only make matters worse. These are a maze of allusions to secret names of God, references to various angels, and arcane details of prayers and procedures. There must have been something extraordinary that took place when the mystics heard such exalted music, but we will never extract it from the surviving texts.

In this chapter, I’ve highlighted the powerful Merkabah tradition. But it matches the quintessential vision quest of Native American culture in virtually every key detail. I hardly need to point out that the practitioners of these two traditions would have no knowledge of their counterparts across the ocean. And there’s no reason to believe that Robert Johnson would have had any connection with either of these spiritual disciplines. Yet, as we showed in the previous chapter, the mythic life story assigned to this blues legend evokes a similar worldview, surprisingly unchanged even in the context of 20th century American society.

Call them what you will—myths or legends or historical facts. But all these traditions converge on a story about songs acquired by a bold visionary on a dangerous journey.

In each instance, the path of enlightenment is always described as a risky trip, so daunting that few are prepared to undertake it. Even the preparation for the journey is difficult—often including fasts or other sacrifices—and is focused on music almost to an extreme degree. The Merkabah aspirant, for example, must sing "many songs and hymns." The travel itinerary itself is even scarier, involving gatekeepers and custodians along the way, who might be dangerous foes or helpful guides—namely, the conductors we studied back in chapter two.

But in each of our case studies, arrival at the highest level is rewarded by music. Finally, the traveler who successfully navigates through these obstacles can then return to normal life, empowered by the music and the experience.

This way of describing religious practices probably surprises many readers. But it really shouldn’t. We’re unfamiliar with this heroic narrative only because religion has become just as codified as music. Or maybe even more codified than music.

Let me ask a simple question: What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word religion?

Many of you are immediately reminded of all the rules and regulations, starting with the Ten Commandments, but encompassing so many other texts declaring “Thou shalt” or “Thou shalt not.” Or maybe you think of creed and dogma, all the doctrines you’re supposed to believe in order to become a member of the team in good faith. Or perhaps you think of ritual and ceremony, with costumes for the celebrants, and all the stylish accessories from incense to stained glass. Or maybe you simply remember the words of some prayer, perhaps one you recited yesterday, or maybe one half-remembered from your distant youth.

But what you probably didn’t think of was ecstasy, euphoria, trance, and out-of-body experiences. That’s not the usual associations with religion in the current day, no matter what your creed (or lack thereof). Yet for the believers of the period that gave us Merkabah mysticism, things were entirely different.

And that just wasn’t true for Jewish initiates who had learned this secret lore, it was also true for Christians—who celebrated saints of their own era famous for their visions. It was true for Gnostics, and for Neo-Platonists. For those ancients we call pagans, it was true of every mystery cult, and there were plenty of them. A spiritual practice that didn’t promise something ecstatic and out-of-the-ordinary was a poor thing indeed. Rules and dogmas are dry stuff by comparison.

Perhaps that’s implies a deficiency in our own religious institutions. But that’s a topic for a different day. For our purposes, we remain focused on music, but you can easily grasp the larger implications of what we have encountered.

These spiritual disciplines always required songs, and in aggregate represent the earliest examples of musicology. But even if you refuse to accept the reality of journeys to another world, you still must have experienced at least a taste of the transcendent power of music. Unlike institutional creeds, music has never abandoned its covenant—which is basically to shake, rattle, and roll; excite and incite; get up and boogie; and totally rock.

Okay, they didn’t use exactly those words to describe things back in the early centuries AD. But they must have felt something like that during their rituals and initiations.

We have now examined a number of traditions that have embraced the power of trance-inducing music, and can identify what they share in common.

I note that many of these practices—for example, the Merkabah mysticism examined above—do not use the word hero. But don’t let that fool you. These traditions are the genuine source of the hero’s journey as it flourishes, albeit degraded and dumbed-down, in current-day pop culture. In fact, these old traditions are the only proven pathway for the visionary journey. We can claim that with confidence because the specific techniques and rituals show so much congruence wherever we encounter them.

We will continue to examine other examples in the pages ahead—for example, in exploring the Arthurian legends of courtly knights and their adventures in pursuit of the Holy Grail, which may be the single most influential instance of quest literature in the history of our culture. Even so, we have already come far enough in this book to define what genuine heroism looks like.

So let me conclude this chapter with a description of the real hero’s journey, which was the original focal point of musicology. I’ll try to summarize it in eight steps.

First and foremost, you must understand that the hero is you. Or, put differently, each of us has the opportunity to take this journey. That was the breakthrough promised in the Derveni papyrus and the Egyptian Book of the Dead, which made an extraordinarily egalitarian and democratizing offer to its readers. Before that time, only gods or military and political leaders could attain a hero’s status. But when these bold musical pathways went mainstream (as we might describe it today) the journey became open to everyone, even you.

Of course, not everybody will take this path. Most people will never even know that the journey is possible. Others may find out about it, but want to avoid the rigors of the trip. The same sources that offer it to us are absolutely consistent on this point. Anyone who aspires to this kind of heroism will need to make sacrifices. So only a few will even start on the path.

Sometimes these sacrifices are just deprivations—fasts or ascetic behavior or even physical pain—but the disciplines can actually take a wide range of forms. They might require intense studies or memorizing specific cultural lore. They might involve approaches to meditation or other techniques that are more psychic than physiological. In fact, there’s a rich web of traditions, which we will explore later in this book, in which sleeping and dreaming are the key techniques for the aspiring initiate.

But in every one of these traditions, we encounter music. And the range of its uses is mind-blowing. The song might form the actual pathway for the hero’s journey. Or the hero’s music is heard at the destination. In other instances, the song is the reward for the trip, and can be brought back to everyday life when the traveler returns home. Or the conductor on the trip is the repository for this empowered music. Or even the vehicle possesses music, as in the chariots described in the Merkabah literature, or in narratives that describe the shaman’s drum as a horse.

This approach to music sounds magical—and I’m not ashamed to use that word, or other metaphysical terms. But everything described here is also scientific, supported by a growing body of evidence—some of it described back in chapter three. Music genuinely possesses transcendent powers, and we can measure it with electroencephalography or electrocardiography, or in dozens of other ways.

But there’s an aspect of this journey which resists quantification or measurement with medical devices, and that's the life-changing impact of the journey on the participant. We are fortunate that so many traditions around the world document this life-changing process—otherwise we might be tempted to dismiss it as something in a fairy tale or fanciful story. Yet given the preponderance of evidence drawn from virtually every geographic area and historical era, there is little room left for doubt. These practices, when pursued by an individual willing to undergo the difficulties with discipline and dedication, are transformative.

And what gets transformed in the process? You answer that by looking within. In this regard, you need to ignore everything you’ve learned from those Hollywood movies, which tell you that heroes defeat crime syndicates, or stop a nuclear bomb from exploding, or singlehandedly rout a terrorist group. If you really go down this path, you don’t triumph over Darth Vader or a James Bond villain. You triumph over your own potential shortcomings and liabilities, your hesitancies, your self-centered behavior, your fears and anxieties.

To put this more concretely, the hero’s path is designed to help us through all the milestones and turning points of human life. Often they are associated with rites of passage that bring a child confidently into adulthood. Or they might be linked with a medical crisis or a soldier’s battlefield courage or some dangerous interlude in a person’s life. In calmer times, they are associated with the achievement of some special wisdom or new-found perspective that could not be attained in any other way. And, of course, the final and largest challenge of human life is incorporated into this tradition, which is what happens when we face the final stage of our biological journey, and what may happen afterwards.

If you think about it, all these things are more important than battling a crime syndicate or facing down a Bond villain. At least they should be. Because for each of us as individuals, this hero’s journey is not designed for entertainment or the applause of audiences. It’s custom-made to empower our lives, tapping into otherwise unreachable possibilities and potentialities.

If certain songs can do all that, we should play close attention to them. So, of course, musical practices of this sort really ought to be a part of that rarefied academic discipline called musicology. Just doing this would change a lot. But even that—as monumental as it is—would only be a start. Because learning about the journey is one thing. Actually taking it is when the magic really begins.

CLICK HERE for Chapter 6 of Music to Raise the Dead: “Can Music Really Replace Philosophy?”

Footnotes

This conveyance is described in the Mahābhārata: These passages can be found in The Mahābhārata, translated by John D. Smith (London: Penguin, 2009), pp. 104. 197, 375]

the sound of the drums becomes the sound of morality: Inscriptions of Asoka, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925), edited by E. Hultzsch, p. 31.

Saint Jerome, in a letter, relates: Jerome’s letter 53 to Paulina, found in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Volume VI, edited by Philip Schaff and Rev. Henry Wallace (New York: Cosimo, 2007), p. 101.

conditions of admission into the circle of Merkabah mystics: Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York: Schocken, 1995), p. 48.

like the noise of great waters: Ezekiel 1:24 KJV.

the enormous figures have no intelligible meaning: Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York: Schocken, 1995), p. 64.

He seats you in a wagon of radiance: Pirkei Hekhalot, translated by L. Grodner, in Understanding Jewish Mysticism: A Source Reader, edited by David R. Blumenthal(New York: Ktav, 1978), p. 72.

many songs and hymns: Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York: Schocken, 1995), p. 57.

Superb work, Ted. Many thanks. A lot of this chimes with the Yoruba musical traditions which manifest in Afro-Cuban music, particularly in the regla de ocha and the attendant use of the drum as a conveyor of divine force.

In his biography on St. Paul, historian and biblical scholar N.T. Wright speculates, an idea not original with him, that Paul was engaged in a Merkabah style meditation on the throne chariot of Ezekiel while on the road to Damascus before his encounter with the risen Jesus.

"There were ways of payer—we hear of them mostly through much later traditions, but there are indications that they were already known in Saul's day—through which that fusion of earth and heaven might be realized even by individuals. Prayer, fasting, and strict observance of Torah could create conditions either for the worshipper to be caught up into heaven or for a fresh revelation of heaven to appear to someone on earth, or indeed both. Who is to say what precisely all this would mean in practice, set as it is at the borders of language and experience both then and now? A vision, a revelation, the unveiling of secrets, of mysteries...like the Temple itself, only even more mysterious...The more I have pondered what happened to Saul of Tarsus on the road to Damascus...the more I have wondered whether Saul had been practicing this kind of meditation." pgs. 49-51

Of course all this is speculation, but it seems to be a matter of historical fact that something happened on that road that not only changed Paul's life entirely, but must be rated as a contender for the most significant event in the history of the world. It's importance and influence is likely also understated due to the fact that it cannot be secularized.

Thanks for the wonderful writing. It's a fascinating read and I've appreciated your other writing too, especially on dopamine culture.