Are Visionary Artists Just Mentally Ill?

A surprising number of creative people have visions, hear voices, or have strange encounters in dreams

It’s risky to be a visionary.

Poet William Blake had his first vision at age four, but telling others about it was dangerous. At age eight, Blake narrowly avoided a beating from his father—saved only by his mother’s intervention—when the child described a tree he had seen that glistened from every branch.

It was like the sky filled with starlight, but during the middle of the day. He told his parents that the tree was shining with the light of angels’ wings.

This was a key moment in Blake’s discovery of his vocation as a prophetic poet. Years later, he wrote in his Proverbs of Hell:

A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees. He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star.

You might be surprised how common this experience is. Annie Dillard describes an ecstatic experience involving a shining tree in her book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Marcel Proust also had a momentous encounter with trees, viewed from a carriage window. He writes:

Suddenly I was overwhelmed with that profound happiness….

And as the carriage moves on, he falls into depression—fearing that he has left something essential behind.

The Persian ruler Xerxes had such a soul-stirring glimpse of a shining tree while marching through Asia, that he adorned it with gold and jewels. Before he moved on, he put a guard on duty to protect that tree forever.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

And then there all those even more famous people who had life-changing interactions with trees—Buddha, Eve, Newton, Moses, etc. (I can only scratch the surface of this rich topic here. I will need to write an essay on this some day—I’ll call it: How to See a Tree.)

Blake didn’t always avoid beatings—both physically and metaphorically—for his tree visions. His mother lost her patience, and hit the future prophetic poet when, on another occasion, the youngster claimed to have encountered the prophet Ezekiel under a (different) tree in the fields.

If Blake has been born 200 years earlier, he would have been celebrated as a seer or saint or shaman. If he were born 200 years later, he would have been prescribed drugs to treat his schizophrenia.

You need to recall that Blake grew up during the Enlightenment—also called the Age of Reason. At the very same moment when Blake had his dangerous vision of the tree, Immanuel Kant—the rigorous philosopher famous for his Critique of Pure Reason—was writing a savage attack on mystics who claimed wisdom could come via visions and dreams.

Blake mostly kept quiet about his visions—or turned them into art. But he never distrusted them. And his prophetic poetry and illustrations are still admired today, when we are even more hard-headed and rationalistic than during the Age of Reason.

You might think that poets stopped having visions in the modern age—or at least stopped talking about them. But that’s not true.

Poet Robert Frost started hearing voices around age seven, and believed he had moments of clairvoyance. But his parents were more tolerant than William Blake’s. Frost wasn’t beaten or drugged. His mother, who also had similar experiences, told him that a few gifted people were blessed with these rare abilities.

“To the end of his life,” the poet’s friend Victor Reichert later related, “Robert believed he could hear voices, real voices. His poems came to him like voices from nowhere. He liked to be alone just to listen, to communicate with the spirit world.”

A few months ago, Daniel Handler—who writes brilliant books for children under the pseudonym Lemony Snicket—shared a gripping and candid account of his ‘haunting’ visions. They started in dreams, but soon entered his waking life. And they have never gone away.

“I am not a crazy person,” he insists.

He doesn’t dismiss the medical aspects of his experiences (nor do I). But Handler refuses to live his life as a mentally ill patient. He rarely mentions these visions nowadays—people get unnerved around individuals who talk about hallucinations. “I stay quiet and I stay in the world,” he explains.

And that allows him to lead a full and vital creative life.

I’ve read all thirteen volumes of Handler (or Snicket’s) grand work A Series of Unfortunate Events—sharing them with my children when they were growing up. So I know firsthand how extraordinary his level of creativity really is. To write like that is a gift.

But perhaps not always pleasant or easy for the gifted.

In recent years, I’ve collected accounts of this sort drawn from the lives of creative people who do work that is literally visionary. Call them what you want—schizophrenics or gifted or whatever—but they are far more common than the general public realizes.

Consider the case of John Frusciante of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Or science fiction novelist Philip K. Dick. Or visual artist Yayoi Kusama. Or Buddy Bolden, the first jazz musician.

I’ve written elsewhere about blues legend Robert Johnson’s alleged ‘deal with the devil’ made at the crossroads at midnight. Many music scholars find this whole story deeply embarrassing, but I’ve probably done more research on the incident than anybody—and I’m convinced that Johnson himself believed in the reality of this encounter.

Was he crazy?

In fact, many artists—as well as others—over the centuries have had similar experiences. I describe some of them in my book-in-progress Music to Raise the Dead.

You might even say that the story of a personal visit to a dark, underworld-ish realm is the most essential tale in our cultural heritage—it shows up in Homer, Virgil, Dante, the myth of Orpheus (which inspired the birth of opera, by the way), the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Finnegans Wake, Native American traditional tales, all shamanic cultures, and many other places.

This narrative is everywhere in the world (or outside of the world, as the case may be).

But these encounters are dismissed now as either idle fictions—or mental illness. And no place in-between those two interpretations is allowed in our discourse.

So for every artist today who speaks openly about their visions, there are probably far more who keep quiet—fearing that their ‘visionary’ gift will be medicalized, institutionalized, or ridiculed.

Or perhaps just disappear.

That last item on the list—the fear that a creative talent will simply vanish one day—is a real concern for artists. At least it was in earlier times. The muses gave them a gift in secret ways that should not be spoken of. Talking openly about it is sacrilege—so much so that the gift might be taken away in punishment.

Until I wrote my book Healing Songs, twenty years ago, I had little interest in these things.

I knew about schizophrenia, and had even seen it up close. I didn’t romanticize it in the least.

Of course, I was aware of thinkers who had tried to reframe it.

I’m still impressed by R.D. Laing’s The Divided Self (1960), an existential assessment of schizophrenia.

I have mixed feelings about other debunkers of the ruling medical paradigms on the subject, such as Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Thomas Szasz—because they push their small portions of wisdom to untenable extremes.

That’s probably also true of Michel Foucault—but, for all his faults and excesses, he at least taught me how easily science can be corrupted by ideology and power.

I’ve also learned a lot about schizophrenia from Iain McGilchrist, who believes that it is linked to certain aspects of our contemporary culture.

But I confronted this matter more intensely during my deep research into healing music, where my rationalistic biases were challenged at every step—and eventually overcome. My study of shamans and trance experiences forced me to accept the existence of visionary encounters that resist scientific explanation, but cannot be easily dismissed as mental illness.

I’ve gradually come to accept that intensely creative people are very similar to these archaic practitioners of trance and ecstasy.

This may seem obvious to many of you. But if (like me) you’re a practicing scholar and professional critic, you are discouraged from talking like a raving mystic. You are prodded into embracing a rationalistic and systematic way of viewing everything, even art and creativity.

The end result is often ridiculous. I see academics who write about music as if it were cost accounting or statistics. They refuse to open themselves up to the magical and mystical part of music—which is the source of its greatest power.

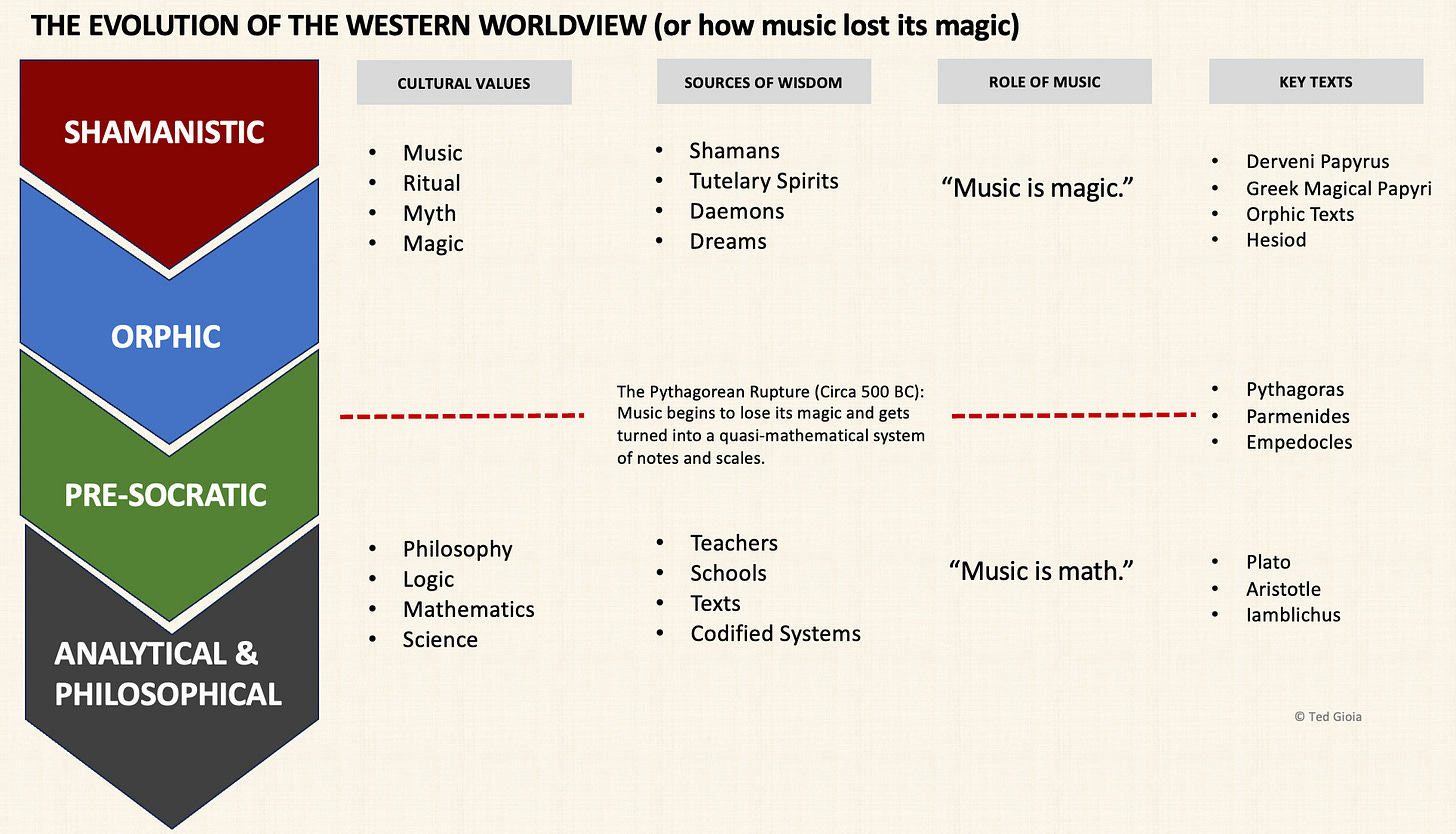

That’s a crying shame. The whole evolution of music as an academic discipline tends to destroy the most important reason to care about music in the first place.

Here’s one of my charts on the subject:

That’s why I started to write about sleeping.

No music writer talks about sleep more than me. And that’s because dreams happen when we sleep—and this is the one type of visionary experience everybody can still access.

We all become a little unhinged and crazy in those dreams. Even the most rationalistic STEM advocate.

Here’s how George Carlin put it:

If you didn't know what sleep was, and you had only seen it in a science fiction movie, you would think it was weird and tell all your friends about the movie you'd seen.

I won’t give you all the back story of my obsession with sleep and it’s connection to creativity—that would take too long. But if you want to get a quick jolt, check out Peter Kingsley’s research into the mystical sleep therapies of the ancient world—where mysticism, philosophy, music, and medicine get all jumbled together.

Could something like this—dream therapy for creatives— exist in the current day?

I wondered about this for a long time. I finally decided to ask musicians about whether they had learned songs from their dreams.

Nothing prepared me for the response I got. I heard from hundreds of musicians—and learned that the gift of a song during a dream is quite common. And it’s usually a powerful song.

This is, of course, the exact same thing that happens in a Native American vision quest, or other shamanic initiation experiences. And it’s been happening for thousands of years.

It happened in ancient Greece. It happened in ancient Egypt. It happened in Siberia, and Australia, and Africa and throughout the Americas.

You go on a journey in a vision, and return with a special song.

If you’ve studied anthropology or folklore, you may know that already. But what you don’t know is how frequently this happens with famous musicians today—and results in a huge hit song.

Two of Paul McCartney’s most successful songs—”Yesterday” and “Let It Be”—came to him in dreams. I note that a poll conducted by the BBC to pick the best songs of the 20th century put “Yesterday” in the top spot.

Keith Richards got the riff for the Rolling Stones’ bestselling song “(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction” while he was sleeping.

Sting’s biggest hit “Every Breath You Take” came in a dream.

Billy Joel’s biggest hit “Just the Way You Are” came in a dream.

Carl Perkins’s biggest hit “Blue Suede Shoes” came in a dream.

Brian Wilson’s biggest hit “Good Vibrations” was inspired by phenomena outside of normal sensory human experience. Wilson’s mother had spoken of these “vibrations,” and told him that dogs bark at things people can’t see.

I could give hundreds of other examples. These visions have always shaped our music, and always will. (In fact, the very first song in the English language whose composer we know by name—“Cædmon's Hymn” from the seventh century—originated in a dream.)

It would take an entire book to do justice to this subject. In fact, I’ve addressed it now in four of my books, sometimes dealing with it at length, but even I can’t pretend to have done more than scratch the surface of this extraordinary (and sadly marginalized) aspect of music culture.

I note that many musicians have told me that they are reluctant to discuss their dream songs. The subject is just too strange and antithetical to our dominant rationalist paradigm.

And that reluctance is even greater if the artist has a hallucination or out-of-body experience or something else that ‘medical experts’ might want to treat.

My hunch is that these happen frequently to intensely creative people—even in an age of rationalism.

The world isn’t as neat and rigorously logical as you’ve been told. And the world of artistic inspiration is the least logical of all. There’s a good reason why the ancients believed that creative works were a gift from the muse.

That may seem like balderdash to you. And even I try to resist this kind of mysticism—but not as much as I once did. That’s because it’s far more plausible than the prevailing scientific theories of creativity.

I continue to research this subject, and I think about it all the time. Even more important, I try to open up my mind to realms of experience beyond the empirical. That’s where creativity comes from, and I don’t want to shut myself off from the source because of close-mindedness.

Above all, I don’t mock or dismiss artists who have these visions, or assume that in every instance they are suffering from mental illness. Some of them might be a lot wiser or healthier than the rest of us.

Ted, I've been wanting to tell you about this for months but never took the time. After this article, I have to !

In 2001, a french musician by the name of Corinne Sombrun was send to Mongalia by the BBC to record sounds for a documentary. To do so she attended a shamanic ceremony so she could record and immediately got into a trance. The shaman told her she was a shaman and herself she had to learn the "craft". She went back to France confused and wanting to know more about what happened to her. She contacted scientists to be studied. One accepted and did exams on her... and immediately advised her to stop to get into trances because her brains looked like a schizophrenic brains.. yes !

She did not. Instead she learned the craft with the Mongolian shaman and spent the last 20 years studying this with scientists.

I'm sparing you the details: she wrote books and there are a lot of conferences on YouTube.. But after 20 years, she devised a way for everyone to get into a shamanic trance (now called "cognitive trance" because it's separated from the shamanic culture) with the help of (wait for it...) sound loops !

The effects of and many uses of trance are still being studied, but it's already proven that it's a capacity of the human brain. They are teaching cognitive trance to psycho-therapists and you can even learn it at the Paris university.

The vision you describe in the article are trances. The description of what it's like to be into a trance that you'll hear about in the videos on YT totally match what you say in the article.

As far as I can see, normalcy and conformity are mental illness.